Читать книгу The Man Who Carried Cash - Julie Chadwick - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4

ОглавлениеTHE SINGIN’ STORYTELLER

As Johnny and Saul boarded the plane at Los Angeles International Airport, the manager couldn’t help but feel relieved at the clear-headed and articulate manners of his travelling companion. En route to a series of dates at The Cave Supper Club on Hornby Street in Vancouver, Saul had been troubled by Johnny’s erratic behaviour of late. Just over a month after Saul was named as Cash’s manager on an official basis, Cash was out on the town in Nashville with songwriter Glenn Douglas Tubb and got arrested for public drunkenness.

Though not entirely scandalous — the two were picked up at 3:30 a.m. near Printer’s Alley on November 15 and released on bond after a four-hour incarceration — Saul nevertheless felt compelled to extract a guarantee from Tennessee ex-governor Frank G. Clement that the charge would be dropped and the incident kept out of the papers. Despite this, a minor story appeared in the Nashville Banner after Tubb and Cash forfeited their bonds. It bothered Saul, and he wanted a retraction.

“The unfortunate publicity that resulted from this incident was directly contrary to the assurance that Johnny received from ex-governor Clement that this would not occur. I would appreciate a note from you as to what our position would be not only demanding a retraction from the newspapers involved, but also what action could be instigated against both the Police Department and said newspapers,” Saul wrote to Bill Morgan of the Nashville-based Morgan-Shelley Music Company. “Since the charge against Johnny was not only not proven, but apparently erroneous in nature, your comments would be very much appreciated.”

It’s unclear why he thought Morgan would be of use, but he seemed to have possessed enough connections to assist with the night in question: Saul went on to thank Morgan for his kindness during the “unfortunate episode,” and added that “I, too, as Johnny’s manager, appreciate your thoughtfulness and graciousness to Johnny. As long as there are people like you left in this business, things couldn’t be too bad.”1

In any case, that issue thankfully seemed to have died out. Saul looked sidelong at Johnny in his airline seat, engrossed in an issue of Time magazine, which he soon tossed on the empty seat next to him. He must have read it cover to cover in just about three minutes, he mused. I suppose he doesn’t waste time on the articles that one shouldn’t waste time over. Saul voraciously consumed magazines and newspapers himself, often ripping out articles and stuffing them into his briefcase for later perusal. He glanced at Johnny again. Maybe there was no need for concern, after all. Perhaps these worrying incidents, though unfortunate, were simply anomalies.

For his own part, Cash had his own concerns to think about. Not particularly fond of nightclub shows, he was not looking forward to his performances at The Cave. He happened to know that Billie Jean Horton would be in town at the same time, as part of a showcase at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre. Furthermore, she would also be staying at the Hotel Georgia. He didn’t quite know what to think. She had been distant recently, put off by his pill-popping, and he hadn’t seen her in some time. She loved him, he knew that, but Johnny Horton had shunned drugs and alcohol, and Cash’s substance use alarmed Billie Jean. She had been through the wringer with Hank Williams, and either she didn’t know how to handle it or didn’t want to; but whatever the reason, she had begun to withdraw from Cash.

Still married to Vivian, a situation that was becoming more untenable all the time, and with his marriage proposal to Billie Jean rebuffed, Johnny had grown bitter and penned “Sing It Pretty, Sue.” It was a song many suspected was about Billie Jean, who aspired to a music career of her own, because it references a woman who cares more about her career than love.2

Known for its spectacular jazz and elaborate striptease performances, The Cave was an upscale supper club venue with high-end, quirky decor that featured velvet curtains, fool’s gold sparkling in dark corners, and stalactites hanging from the ceiling. Tuxedoed ushers greeted patrons at the door to escort them to their tables. With a capacity of about eight hundred, it was typically packed, especially on nights with big-name stars like Lena Horne.

Upon their arrival at the hotel, Johnny immediately went for his pills. Swiftly the calm, rational man that Saul had made note of on the airplane disappeared and was replaced by what Saul observed to be an entirely different person. By the time he stumbled backstage, Johnny was bouncing drinking glasses off the dressing room walls, leaving a wake of broken glass.

In between shows, Johnny went into Red Robinson’s Vancouver studio for an interview, though it was short-lived. “All of a sudden, I look over — I asked him a question, no answer — he’s fallen asleep at my desk because he’s gassed,” said Robinson.3

On the evening that Billie Jean was in town, Cash returned to the hotel and stormed down the hallways in search of her room. Pounding on the door, he threatened to break it down. The two argued, and she pushed him from her doorway and locked it. Enraged, Cash turned and ran the length of the hallway, shattering all the antique chandeliers hanging in his path.4

“True enough, they should have been smashed because they had to redo the whole hotel anyway. Certainly after he left, they had to redo it,” Saul recalled. To his credit, Johnny paid for the damages before their entire entourage was then thrown out of the hotel. By the next day, just as dramatically, Johnny settled back into his role as a pleasant travelling companion. The two men flew to Los Angeles and rented a car, and as they drove from LAX to Johnny’s mansion in Casitas Springs, they calmly discussed future career moves and Johnny’s possible purchase of a new car. Saul studied his client’s profile as they drove. It was curious. Once again, everything had changed. It seemed as though there was never any certainty about just who, exactly, you were speaking to at any given moment.5

At this juncture Saul had his work cut out for him. Not only did he already feel drawn to become Johnny’s protector and defender in a capacity that extended far beyond typical management duties, but Cash’s career was also lagging. Though he and the Tennessee Three had enjoyed regular performances on a wide variety of music shows like American Bandstand, and were more recently featured on Five Star Jubilee and Here’s Hollywood, attempts to branch out into television and film as a bona fide actor had fallen flat. A lead role in the ultra-low-budget crime drama Five Minutes to Live, in which he invested twenty thousand dollars of his own money, had floundered, and the reviews were scathing.

Musically, he was also adrift, and the dismissive Toronto Daily Star review wasn’t a one-off. The amphetamine-induced weakness in his typically rich baritone got so bad that criticism was trickling in from radio DJs, who until this point had been Cash’s greatest fans. “Tell Cash that if he ever makes another record as bad as ‘Locomotive Man,’ don’t even send it, because I’m not ever going to play it on the radio,” prominent Des Moines–based promoter and DJ Smokey Smith told Johnny Western. The pills also interfered with Cash’s motivation and ability to record. It had been two years since he had released a hit album, and in the spring of 1961, Cash wasn’t on any charts, country or otherwise. Earlier that year, in May he relented to Columbia’s request that he take a 50 percent cut to his royalties on the sales of his next two records.6

Despite this, ex-manager Bob Neal wrote to Cash on October 24, pleading with him to revive their partnership. Neal had fallen on hard times. Previously a DJ on Memphis station WMPS, he had managed Elvis until Colonel Tom Parker elbowed him out of the picture. He struck gold again with Cash in his early days at Sun Records, but was soon edged out in much the same manner by Stew Carnall. In 1958 he decided to buy radio station KCIJ in Shreveport, Louisiana, but three years later he ran into trouble. Desperate, he reached out to Cash.

“I waited all day the other day for your call,” Neal began the letter. After some preliminaries of asking how Cash’s tour of eastern Canada went, he then explained that he wasn’t doing so well himself. In fact, he was in way over his head at the station; “hanging on by his teeth” after losing everything he had in the venture. The possibility that he would have to turn the station back to its previous owner looked imminent. With this established, he made a plea to Cash: “Have you thought about the possibility of putting together our old Winning Team again? You know, with your talent and ability and my knowledge of the business, we had it going mighty good for a while,” he wrote. “I don’t know yet why we fell apart, but I do know that everything I built and was building for you was based on good solid realities.”7

Johnny replied almost immediately on stationery that indicated the address of the new office he had just opened on Main Street in Ventura, California. The tour had turned out well, he wrote back, despite the sheer lack of people in Newfoundland. He had a new promoter working for him, a Mr. Saul Holiff, who had already done a great deal on his behalf. Not only had Saul recently travelled to the Far East to look into a tour, Cash wrote, but he had also practically set a date for him at Carnegie Hall. “Also, he went with me to New York about three weeks ago and raised a lot of hell on my behalf, resulting in a relationship with Columbia Records that is and has been needed for a long time. I honestly think things are really going to swing now. Columbia is getting behind the Carnegie Hall deal as well as all the other things we laid out.”

That was about as far as Cash went in directly answering Neal’s request for a reconciliation, but his position was clear: For now, Saul was his right-hand man. Throwing Neal a bone, Cash added that he had some upcoming dates in Iowa and Wisconsin and had suggested to Saul, who would join him in Ventura in about two weeks, that they could perhaps arrange for Neal to promote those shows.8

Despite Johnny’s lukewarm status, Saul was still determined he would be a superstar far outside the conventional confines of country music, and, as Cash mentioned in his letter, Carnegie Hall was the next stop on the road map to getting him there. During the Columbia meeting Saul made sure to mention it as a signal of his intentions, and he had to make good on his promises, not least because of the burning sense of insecurity that fuelled much of them.

“I guess I felt that I never should be his manager,” Saul later confessed to a reporter. “This is as close to the truth as you’re ever going to get from me. I couldn’t find any way to justify why I was doing what I was doing, so I thought I had to keep performing. As a non-performer, I still thought I had to perform. And the only way that I thought I could perform was to come up with something that hadn’t been done before that would excite him, and that I was part of the reason he got excited.”9

Within weeks of the official managerial announcement, Saul moved to California and continued to mull over just how to package Johnny in a way that shifted him outside the confines of country music. He wasn’t anxious to play up the “country” label, because labelling was serious — if an artist became lumped into a certain category, it meant restricted airplay.10

He rolled the issue over and over in his mind. There was something that had hooked him when he had first heard Johnny’s music, as country wasn’t his taste. What was that unique quality that I heard, the thing that elevates him to a place where people relate to him? he wondered, rewinding back to the first Cash song he had heard on the jukebox in 1957. He pored over what his own feelings had been. And just as quickly, he knew. He’s a storyteller. That’s the way he approached putting a song together, like “Five Feet High and Rising,” and the reason he chose to sing songs about subjects like farming and poverty in the rural south. That’s what his people lived. And that’s how he should be portrayed — “America’s Singing Storyteller.” It was perfect, and just nebulous enough. Beginning with a bold red, white, and black palette, he swiftly envisioned a press kit package built around this idea.11

Modelled on an Old West poster, it featured an intense close-up of Johnny’s face — primarily his dark eyes — overlaid with a shot from the waist up, playing the guitar. Above, it read “Wanted” in Old West–style font, and underneath, “Johnny Cash: Americana’s Most Wanted Singin’ Storyteller.” In case there was any doubt, smaller text below that assured Cash was a “Song Singin’, Gun Slingin’, Cash Register Ringin’, Entertainer…. Here is a man who packs ’em in every time he calls a meetin’ … a man whose face and voice are known the length and breadth of the land … a man whose arrival in any city, town, or village starts people to talkin’, whistlin’, and toe tappin’, in anticipation of seeing and hearing him.”

The moniker of “Singin’ Storyteller” stuck, and it took on different incarnations over the years as others picked up the catchy phrase and ran with it. But it was innovative and did the job.12

The Carnegie Hall show was the next piece of the puzzle Saul needed to lock down. As a venue, it was the perfect backdrop to crystallize what had become his grand vision of a travelling country music extravaganza. Who else could he imagine on that stage? There was no question that women filled out the show and offered both a balance and an edge to the performance. This presented a dilemma, however. On the Newfoundland tour there had been another significant setback, and this one involved Rose Maddox. Halfway through the tour she had received news from her husband, Jimmy, that their son had signed up for the U.S. Marine Corps. Devastated and concerned for his safety, she told Cash she had to leave immediately and dropped everything to fly home to Oceanside, California, in an attempt to stop him. She never returned, and it was the last tour she ever worked with the troupe as their featured female singer.13

There had been other issues, too; though she was unaware of Cash’s growing drug problem, Maddox was beginning to tire of his unreliability and the rescheduling of show dates it entailed. When he flew off to placate Vivian during their Newfoundland tour, it had simply driven a point home — that his domestic conflicts were not improving. There was also a sexual tension between Maddox and Cash that had gone unrealized, until one night in a hotel room after a show in Calgary. Lying beside her in a bed, Cash tossed and turned and finally left, saying, “I’m goin’ back down to my room. I can’t stand bein’ this close to you.”

Surprised by his interest, Maddox later confronted Cash, who tried to convince her to be with him. “I want you completely or not at all,” he said.

Maddox curtly informed him she had no intention of cheating on her husband, but he continued to pursue her, which only added to her discomfort and eventual decision to leave.14

Fond of Maddox and appreciative of her reliability and talent, if nothing more, Saul was at a loss. Aside from the designs he had on Carnegie Hall, they had a number of upcoming performances peppered with notable venues like the Dallas Sportatorium, which was to host the Big D Jamboree in Dallas in early December, and the KRNT Theatre in Des Moines, Iowa. He needed someone reliable, and a crowd-pleaser. Patsy Cline was a possible replacement. “One of the boys,” as Johnny Western liked to say. She was a hard-drinking, dirty-joking road veteran with a wide smile and raucous laugh, and had toured with Cash previously. Renowned for her emotional delivery, her popularity was swiftly rising. “I Fall to Pieces” had hit number one on the charts earlier in the year, and she was the first female performer in that era to both demand and receive equal billing with her male counterparts.

The year 1961 had been a whirlwind for the singer, from the birth of her second child to her growing star power, which was highlighted when she joined the Grand Ole Opry and then took the stage with more than a dozen Opry performers at Carnegie Hall in November of that year. A near-fatal head-on collision in June had sent Cline to the hospital for a month and left her with a severely scarred forehead, after which she soon hit the road again — on crutches — and made it back into the studio by mid-August to record “Crazy,” penned by little-known singer-songwriter Willie Nelson. She first heard the song when her husband and manager Charlie Dick drove Nelson out to their house at 1:00 a.m. and pulled Cline out of bed to listen to it.15

Likely Saul’s first choice for the upcoming Big D show on December 9, Cline probably turned down the invitation due to exhaustion: by mid-December the singer had been diagnosed with “a nervous breakdown” and was prescribed two weeks of bed rest. Besides, once the knockout success “Crazy” — a pop hit as well as a country one — climbed the charts, she began to command top dollar, which made her a little pricier than Maddox. However, Saul kept her in mind as an asset for the bigger shows like the Country Music Extravaganza he was planning for the Hollywood Bowl. In the meantime, they needed someone quick for the Dallas performance on the Big D Jamboree in Dallas on December 9; someone who was affordable, charming, and possessed of an enigmatic stage presence.16

“We need a girl singer on the show,’” Saul said to Johnny when they next spoke. “They want more than just you and your band.”

“Well, get one,” said Johnny.

Saul thought for a moment. “What do you think about June Carter?”

Clever and confident, June had been a veteran stage performer since the age of ten and hailed from the legendary Carters, considered one of the founding families of country music, though their reach and influence had waned in recent years. Johnny had grown up hearing June’s voice on XERA radio, a border station with a strong signal out of Del Rio, Texas, and the first time he had ever seen June onstage at the Grand Ole Opry he’d been just a teenager. On a field trip with his classmates from Dyess High School, he watched enraptured as she sang and played guitar and five-string banjo, and performed a sort of comedy routine alongside the Texas Troubadour, singer Ernest Tubb. It seemed funny now in hindsight, because the songwriter with whom Johnny had recently been carousing in Nashville was Glenn, Ernest Tubb’s nephew.

Johnny grinned at the memory of June’s onstage antics. “I’ve always been a fan of hers. Get her if you can,” he told Saul.17

In the days leading up to his performance on the Big D radio show, Johnny may have reflected on another meeting he’d had with June Carter, which later became one of his favourite stories. On July 7, 1956, he visited the Opry again, but this time as a performer. After an introduction from June’s husband, country singer Carl Smith, Johnny launched into a performance of “So Doggone Lonesome” in a sombre black suit and ruffled white shirt, a contrast to the sea of cowboy hats and checkered flannel. It was the first number of a three-song set, but it was backstage that was most memorable for him. That was where he ran into June, who recalled that while they talked his “black eyes shone like agates.”18

Already familiar with Johnny Cash, June had heard his music while touring with Elvis as part of the Carter Family, Elvis’s opening act. While on the road, Elvis would incessantly pump nickels into jukeboxes and listen to Cash’s songs whenever they stopped to eat at diners. Elvis also tuned his guitar by singing the opening line to one of Cash’s songs.19

Like June, Cash was also married, and his “I Walk the Line” ode to Vivian was then climbing the charts. The way Cash told the story of that first meeting is that he walked right up to June and told her he was going to marry her someday. “Well, good,” she said with a laugh. “I can’t wait.”20

It would be five years until the pair met again on the Big D show, and Johnny was late.

Aired from a large multi-purpose arena called the Sportatorium, the Big D Jamboree was a barn dance and radio program fashioned in the manner of the Grand Ole Opry and Louisiana Hayride. The barn-like venue featured an octagonal seating arrangement that could hold more than 6,300 spectators, though it was primarily used to host wrestling matches. Aside from seating the audience, the arena offered performers an opportunity for exposure through its radio show on KRLD, which had such a wide range it reached listeners in forty states. By the early 1960s, competition with television had begun to affect audience turnouts and interest in country music variety shows had begun a slow decline. Despite this, Saul felt it remained an important tool for exposure.21

Busy with the band’s two sets, Johnny didn’t even see June until after the show. Bound for a show in Oklahoma City later that night, Cash, Johnny Western, Gordon Terry, and Marshall Grant prepared to bundle up into one car. As she was also booked for the same show, between sets June had asked Marshall Grant — whom she had just met — if she could tag along for the ride. When he hesitated, thinking of how crowded the car would be, she assured him she would be happy to just sit on someone’s lap. By the time the gig was finished and Johnny realized what was going on, he quickly volunteered to share his seat. The group piled into the car, and June sat on Johnny’s lap. En route, snowflakes began to descend slowly outside the windows, eventually becoming a swirling snowstorm. By the time the car chugged to a stop outside their venue in Oklahoma, the performance had been cancelled due to the weather. Their show may have been over, but June’s long-term association with the Johnny Cash Show had just begun. And perhaps more importantly, a seed of attraction between her and Johnny had been planted.22

By mid-December of 1961, Johnny had given Saul power of attorney over his affairs. As Christmas approached, Saul decided to formally invite June to become a permanent part of their show; in fact, he would eventually request that she bring on the whole Carter family of musicians. It was a nod to bona fide country royalty, which both he and Johnny liked, but for now at the very least he needed June. She was a dynamo onstage, and damn funny. She was also professional and reliable, an increasingly valuable commodity as the complexity and calibre of their shows was incrementally raised.23

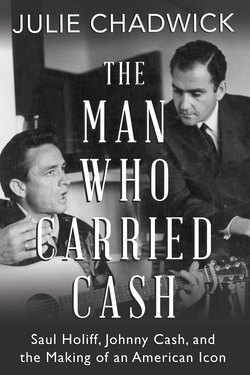

Saul Holiff and June Carter in the back of a limousine after a show, circa 1962.

The next performance was at the KRNT Theatre in Des Moines, and it would be an even larger and more extravagant affair than the Big D. Saul needed to be certain of June’s presence. Even more important was the Carnegie Hall show, for which he had now confirmed a date in early May. Cash had no arguments with Saul’s plans with June, and had so thoroughly enjoyed the car ride to Oklahoma that he made certain to tell the other guys in no uncertain terms that when it came to her, it was “hands off.”

“Don’t mess around with June Carter,” Johnny told them. “I’m watching over her like a big old rooster.” Though it sounded funny, he wasn’t laughing.24

With no objections from Cash, Saul went ahead with pulling June in on a more permanent basis and picked up the phone. To his delight, she was open to the idea. Carnegie Hall was likely a go for her as well, she said, if he’d type out the request and terms of agreement and send it to her in a letter. This would make two female singers for Des Moines, as Saul had just heard back from Patsy Cline, and she was also on the roster. It was all proceeding swimmingly. As Christmas Day dawned clear and bright, Saul sat down and composed a letter.

December 25, 1961

Dear June:

It was very nice talking with you the other night, even though I did make like a remonstrative paternal father.

This letter will confirm your appearance at the KRNT Theatre in Des Moines on January 28th. As we discussed by phone, your return transportation is to be paid by JOHNNY CASH, and if we draw as well as the previous engagement there, an additional $100. […] This time, as you know, we have George Jones, Carl Perkins, Patsy Cline, and, of course, June (“The Heel”) Carter. (Smokey Smith already is pushing “The Heel” like crazy; he has got his “heel” and “sole” in it.)

I would also like to confirm the appearance of you and all your assorted relatives at Carnegie Hall, Thursday, May 10th, with the fee to be $500 for you and your family, plus cost of transportation by car from Nashville to New York and return, and I might even buy you a steak as an additional bonus.

It is understood that you will arrive in New York on May 7th in order to have ample opportunity to assist in the last-minute exploitation of the May 10th appearance.

I will endeavor to fill any additional dates if at all possible, and will advise you subsequently.

I will also try to arrange an appearance in New York at the Village Gate so that an extra source of revenue, plus exposure, may be secured for you and your family.

The very best to you and your family for the new year, and I do look forward to seeing you once again in Des Moines.

Yours for Bigger and Better Heels

JOHNNY CASH INC.

Saul Holiff

Personal Manager25

Within days he would hit the road for a short trip to Las Vegas, but before he departed there were some issues to discuss with Johnny.

With much effort, they were finally getting his jumbled affairs into some semblance of order at the office in Ventura, as various wrinkles left over from Stew Carnall were ironed out. The office itself was a modest affair on 433 East Main Street, which Saul had furnished with a few minimal items: a lamp, a teak desk, and a wooden swivel chair. Behind the desk he mounted a huge map of the United States that took up much of the wall, which not only gave the space the feeling of a war room but also allowed them to map out upcoming tours.

Tasked with the process of streamlining operations was their new office assistant Betty Siegfried, whom he instructed to implement a new filing system for cheques, finances, records, and publicity materials. Cash’s finances were in an incredible state of disarray, and the previous accountant had essentially “filed” items by tossing them into cardboard cartons. There had been no attempt to put them in order, or submit any tax returns for at least three years. I have inherited a massive headache and an extraordinary mess, Saul thought when he first surveyed the wreckage. It would take some untangling to make it functional, but with Betty’s help he felt up to the task.

The move to Los Angeles had been personally stressful. Upon Saul’s midnight arrival at LAX, Cash was nowhere to be found, so he had hailed a cab to travel the almost one hundred miles to Casitas Springs. As they pulled up to the driveway, he rummaged around in his pockets and realized with a sinking feeling that he hadn’t brought any American money with him. The cab driver simply shook his head when he offered Canadian bills. So, although it was about 3:00 a.m., he had to bang on the door and wake up Vivian.

Johnny Cash and Saul Holiff at the Johnny Cash Incorporated office in Ventura, in the fall of 1961.

It was a rocky start to a life that Saul feared he might be ill-equipped to handle. Now dividing his time between London and Los Angeles, living in a motel, without a car, and with net assets at about four thousand dollars, it was a struggle to keep his insecurity at bay. And in the midst of it was the sickening realization that he had entered a bit of a madhouse. Johnny’s marriage was obviously troubled, and he appeared to have some kind of manic-depressive issues due to (or exacerbated by) his pep pill addiction. In addition to the protective inclinations Saul felt — as Johnny was lucid and eminently likeable when he was sober — he could see that this job would require him to be a counsellor, accountant, adviser, agent, and psychiatrist, among other things. Was he ready? He didn’t know.26

Johnny’s Christmas in Casitas Springs was celebrated with typical extravagance. Decorations were trailed all the way up the hillside outside their home to the mountain peak, where he installed a ten-foot light-up aluminum cross. Oblivious to how much their family already stood out as a beacon of wealth, perched above the modest, tiny community in a five-thousand-square-foot mansion, he had proceeded to blare Christmas music from an amplifier on his roof every year until the neighbours complained. At one point, sheriff’s deputies were dispatched to deal with the noise.

“I didn’t think there was a Scrooge left,” Cash muttered in response, and yanked the plug out halfway through “Joy to the World.”27

At their office in the city, Saul waited for June’s reply and feverishly looked for ways to occupy himself as the holidays slowed the flow of work to a muddy pace.

He lit a cigarette and began to dictate a letter to Johnny, as Betty scrolled paper into the typewriter. “Dear Small, Sad Sam,” Saul began. He exhaled. “Enclosed are a few things I thought might interest you.” They were listed off in order: First, a poem that his girlfriend Barbara Robinson had composed about him that had fluffed his ego. “Thought you might enjoy it,” he noted nonchalantly. Also included were some articles on Goddard Lieberson that he had sent for and had finally arrived, and a clipping that included a description of a fabulous new tranquilizer he had on order for delivery. Now for the items of business.

First up were issues with Columbia executive Dave Kapralik, Lieberson’s second-in-command, which had gotten under his skin. Pressure had been maintained on the Columbia executives regarding when and how Cash’s albums were to be released for maximum exposure, and Kapralik was now throwing roadblocks up in front of the plan. They had clashed in particular over “The Big Battle,” a Civil War–era song Johnny had recorded in March, which covered the topic of war in a way he felt passionate about.

“Summarized below are some ruminative thoughts, plus some new developments,” Saul said as Betty typed. He began to pace. “One. Kapralik — he told me in Nashville, and then again in New York, that he would check with Law regarding ‘The Battle’ after Don was discharged from hospital. Now he tells me that only Don Law is responsible for your releases and that, as far as he knows, no artist has final say as to when a release should be made or, for that matter, what release will be made. Apparently it is a mutual situation.”

He paused, recalling Kapralik’s tone.

“He rather snottily advised that it takes at least sixteen weeks from the time material is complete to get an album on the market. He spoke in a spooky fashion,” he said, waving his hands around, trailing smoke. “Condescendingly — and got me mad. I’m afraid I expressed my anger. Suggested you could and would write a sequel to ‘Ride This Train’ for Carnegie Hall if Columbia would record at the Hall. Told him this was my idea and wasn’t a prerequisite to your doing the sequel. However, it might give you the impetus nevertheless to do so. He replied by saying that you shouldn’t need any encouragement to come up with additional material. I got madder. So much for Kapralik.”

Saul stubbed out the cigarette in his desk ashtray and ran a hand across his dark, wavy hair, which he had recently cut quite short. Dressed in his trademark black, he had taken to wearing short sleeves to better deal with the heat in California. It was nothing like the chilly, snowy winters he was used to in London.

I’ll call Don Law in Johnny’s presence, thought Saul, divining how he might approach the issue differently. Johnny’s producer at Columbia and head of their country music division, Law seemed to be providing little direction for his client, preferring to let Johnny do just as he pleased, rather than take the reins and offer guidance. Saul lit another cigarette as Betty blinked, fingers hovering above the typewriter keys. He will have to go, he thought, making a mental note. Next on the agenda: Carnegie Hall.

“Two. Will write Lieberson about plans for Carnegie, plus giant Johnny Cash ‘thank you’ Caribou Cocktail Party in New York. Plans for this party have jelled in my mind, and I am sure it will set the industry on its musical ear. I’ll fill you in next week and see if you concur,” said Saul. It put him in a better mood to think about plans for the pre-Carnegie party, the aftermath of which he felt certain would reverberate in their circles for some time. Finished with business, he decided to remind Johnny of some personal issues they had discussed during their many long car rides between LAX airport and Casitas Springs. Though he was clearheaded at the time, Johnny often had a hard time recalling these conversations.

“I’m so pleased with your new attitude toward our future plans, but after doing some extensive reading on other artists I have come to the overpowering conclusion that an artist, to properly flourish and prosper, absolutely must be concerned with self-discipline, and even more concerned with the need to grow and mature with the passage of time.” Saul scratched his jaw, thinking. He began to tread the carpet again. “This, in my opinion, calls for an honest appraisal of what the artist really wants. If he is truly ambitious and admits it, then it means work, concentration and a level head. I sincerely believe that you are capable of great things — far in excess of what you have accomplished up to date — providing you keep a level head and an even perspective. Forgive me for lecturing and preaching, but this is how I feel.”

“See you soon. Happy New Year,” said Saul. He nodded at Betty, and a smile hovered at the corner of his mouth. “Sign it, ‘Preacher Holiff.’”28

This reflective tone continued upon his return to Los Angeles after the Vegas trip, where he spent New Year’s Eve alone in his motel room ruminating on all that had come to pass in the last few months, and all that would shortly come to pass. He often missed his girlfriend, the kind, insightful secretary Barbara Robinson. She was beautiful, too — refined, with a wide smile, a long, slim neck, and tidy chestnut hair. The poem she had written about him, which he had forwarded to Johnny, was titled “Mister 17,” and was inspired by his obsession with the number seventeen. Though he knew better than to engage in such superstitions, the number seemed to recur as a prominent “thing” in his life. “You’re a practical sort of fellow / Who believes in Logic only / While astrology and tea-cup reading’s / Balm for the lonely,” she had written. “But isn’t it peculiar / That you never fail to notice / Any time the number 17 / Might come within your focus?”29

The intimacy of her overture had touched him, and it was clever. He liked that. As his management of Cash expanded, he sought Barbara’s assistance and opinions in many areas of the business, and she was already becoming near-indispensable to him in that capacity.

It was back in November of 1957 that Barbara had traded her hometown of Winnipeg for London, Ontario, and worked her way into a job at the London Free Press. It was the city’s daily paper, and she served as the personal secretary to their dynamic advertising director, Charles Fenn. For years, Saul had visited the newspaper’s offices to purchase ads — first for his clothing store and then later to promote Sol’s Square Boy and his rock ’n’ roll shows. Not long after Barbara’s arrival, Saul immediately noticed her, though he wasn’t certain she had noticed him back. In fact, he had first seen her outside of the newspaper office, in a booth at the nearby Greek restaurant where the newspaper staff took their coffee breaks. As she laughed with the other secretaries, Saul sidled up to owner Victor Mahas to ask if he knew who “that woman” was. Feeling protective, Mahas looked Saul up and down and shook his head no, though she was in fact a friend. As Saul departed, he hoped he would get another chance.

A short while later, Barbara was in her office — a windowless cube on the upper floor near the copy services section — immersed in the discussion of an advertising contract with one of the newspaper’s part-time temps. A shadow crossed the page they were focused on. She glanced up just in time to see a man pass by the open door of her office.

“Who was that?” Barbara asked her co-worker.

“I can’t remember his name. I think he’s a tailor?” She shrugged.

Hours later, Barbara was bent over her desk at work when she heard a voice behind her.

“So, what kind of music do you like?”

Startled, she looked around. She hadn’t heard anyone come in. It was the man, the one who had passed by earlier. She thought for a moment. No “hello”? No introduction? And that’s a funny question for a tailor to ask.

“Well, I like pretty well anything, except country music and rock and roll,” she said with a smile. At this, he laughed.

“Don’t you know who I am?” he said. A smile lingered around the edges of his mouth.

“No, I haven’t seen you until today.” The question made her nervous. Executives’ secretaries were supposed to know everything and everybody.

“My name’s Saul Holiff. I promote concerts in the area,” he said, hands in his pockets. “They’re usually country music or rock ’n’ roll.”

“I guess that’s why I’ve never met you before,” she said, and then allowed herself to laugh.

Just before the end of the day, the phone rang. It was Saul, calling to ask if she would like to come over to his apartment and listen to the new hi-fi equipment he had just got installed. A music lover herself, she had heard about the advances in sound that this new technology had promised. Curious, she accepted.

Little did she know that this was not the first time she had encountered Saul, either. As they began to date she realized why he looked familiar — years earlier when she had first moved to the city, Barbara had been in the audience when Saul performed with the Little London Theatre’s production of The Teahouse of the August Moon. The acting wasn’t the best she’d ever seen, but he had a brooding quality that was so charismatic she couldn’t take her eyes off him.

By the next year, the two had grown close — Saul now regularly consulted her advertising expertise on everything from Johnny’s press kit, which she designed with her colleague Jerry Davies, to his new stationery that featured flashy gold embossing and a JRC logo in the shape of a crown — but at times she had doubts about her dynamic, intoxicating new boyfriend. Though he respected her intelligence enough to take her advice, he was also pushy and impossible to disagree with. Unyielding, even. It seemed at times that if she said black, he’d say white — just for the sake of it. And no amount of arguing would convince him otherwise. When she needed to leave at the end of a date, he’d always convince her to stay. Just one more show; just ten more minutes. Sometimes it seemed attentive, but at other times it felt oppressive. And then there was that trip to Mexico.

At the end of October she had won a trip to Mexico through a promotion with a local theatre company. Saul immediately assumed his inclusion on the journey as her plus-one, but it then provided a unique dilemma for Barbara. Only newly dating, she was reluctant to involve herself in a scandal by travelling alone with a man who was not yet her husband. It just wasn’t done. Saul suggested a variety of excuses, people she could say she was going with, including his mother or a girlfriend, but the possibility of lying made Barbara even more uncomfortable. The prize included a double hotel room, so eventually she caved, and with the explanation that they were soon to be married, managed to clear it with the hotel and at least arrange separate rooms. Incensed, Saul then refused to pay for his own room, which she found ridiculous.

The obnoxious behaviour continued once they arrived. Saul soon made his acquaintance with the local pool boy, and over the next few days he delighted in challenging him to a round of competitive poolside push-ups. Exasperated, Barbara filled her days with walks on the beach, often to escape his company (though she was loath to admit it) and clear her head. Typically, the two spent their evenings dining together at the local restaurant, after which they would arrange to borrow a jeep from the head server.

One evening, after the two had gone on a tour of the local area together, they returned to find Barbara had received a letter from the head server, proposing marriage. Flattered but confused, she demurred with the explanation that Saul was her fiancé and they would soon be married. “Married? I thought you were his secretary,” the head server wrote back.

Barbara was floored. Had he told everyone she was his secretary? And neglected to inform her? There was no risk of scandal at this point. Was he embarrassed to be with her? She felt as though she were under water. It was clear she was already in over her head with this man, whose powerful personality easily overwhelmed Barbara’s sensitive, empathic nature. Naturally a giving person, she had begun to notice a predatory quality in the way Saul operated, and it made her uneasy. Though she already knew she was on unequal footing with him, there was one person who seemed, strangely, a match for Saul Holiff. A man who also saturated the air of a room when he entered it — and that was his new client, Johnny Cash.

When Saul had first told her of his agreement to become Cash’s manager, Barbara was concerned. The scandal of Jerry Lee Lewis’s marriage to his thirteen-year-old cousin was all over the news. What kind of people are these, exactly? she had wondered, with a sense of both curiosity and caution.

She would find out soon enough.30

Johnny Cash and fans, backstage in London, Ontario, 1962.

Though Saul had taken up residence in Hollywood to keep a close eye on the comings and goings at their Ventura-based office, he retained a small bachelor apartment on King Street in London to serve as his Canadian base. It was here that Barbara first encountered Johnny at the end of a ten-day tour through Ontario, earlier that year. After their final show in Sault Ste. Marie, Saul had asked Barbara to be on hand at his flat that evening to help serve drinks and snacks to the entourage while he showed off his new hi-fi stereo system.

The apartment was so tiny that his primary sink was the one in the bathroom, so Barbara had decided she would wash the limited dish supply in there as she went along. Excusing herself, she had just about finished a sinkful when, from the corner of her eye, she saw Johnny enter the bathroom. For a moment she had figured he’d mistakenly barged in, and kept washing. The door was slowly pushed behind him until it clicked. She stared at the dish in her hands and kept the cloth moving across its surface. What do I do? She glanced at him.

“Hi,” she offered, hands still immersed in the water.

She began to re-rinse the dishes. Johnny had remained in front of the door, an awkward expression on his face, and began to chatter. Something about his gun collection. Barbara had stared past her reflection at him and tried to focus on his words, but there were few topics less interesting to her than guns. Is he trying to test me? See if I’ll throw herself at him like all the other girls? She pulled out the plug. Maybe he wants to create the impression that he’d had another conquest. And with Saul’s girlfriend, no less. Nice try.

She held her breath and willed him to stay where he was. Years earlier, it had seemed his track “Don’t Take Your Guns to Town” always came on the radio right when she arrived to work. It was uncanny. At the time she had found the song strangely compelling, not least because of the sheer originality of his voice and style. It was unlike anything she had ever heard before. However, by this point Cash was little more than a name, another client upon whom she and her colleague Gerry Davis expended a fair amount of creative energy to design press kits and fancy letterhead. And now that the body had been linked to the name, she needed it to move out of the way.

Gathering up the dishes, she had turned with the stack in her hands. To her relief, the knob turned behind him and he released the door.31