Читать книгу The Man Who Carried Cash - Julie Chadwick - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3

ОглавлениеWHEN SAUL MET JOHNNY

As with so many things in his life, Saul’s ascent in the world of music promotion was built on a foundation of research. In this case it meant regular trips to Heintzmann’s, the record store on Dundas Street, where he would walk his fingers through records for hours. It was a musical hub for not only London but also all the surrounding districts. At the epicentre of its teenage section stood Dave Roberts, a sixteen-year-old music aficionado with a deft ear cocked toward what was up-and-coming, who reigned over Heintzmann’s back counter and listening booths, where teens flocked to check out the latest records.

Initially a customer, Roberts made incessant musical requests that eventually landed him a job at the store after the employees realized he knew more about what the kids were listening to than they did. He was a smart kid, and had a deft handle on what was hip. From there he grew to become a source for radio DJs and promoters on which records were moving fast and who was going to be the next big thing. Clever enough to know what he didn’t know, it wasn’t long before Saul realized Roberts had what he needed.

“I knew a lot about what could make a hit and what didn’t, so I did get called on,” said Roberts. “Saul used me as a sounding board to say, ‘What’s cooking? What should we be doing?’”

Saul wanted to know about Johnny Cash, who first caught his ear when he heard “Five Feet High and Rising,” his ode to a childhood flood, on a jukebox a couple of years earlier. Bob Neal had set down a solid offer for an August 16 date for Cash, at the cost of $1,250, and he needed to know more. Primarily in charge of overseeing the pop section, Dave was the first to notice when hits like Cash’s “Walk the Line” began to make their crossover from country. The trend was clear, and it was Dave who first insisted that, as an avid listener of a variety of stations, like WSM out of Nashville, it was imperative that Saul look into expanding his promotions to include country musicians. The names of country stars like Merle Haggard, Johnny Horton, and Eddy Arnold were still unfamiliar to Saul, but that was about to change. In return for Dave’s help, Saul would often take the teenager out to shows with him in style, picking him up at his modest home in west London in a white fin-tailed Cadillac Eldorado. The image of Saul’s elegant car coasting to a stop outside Dave’s house was a sight the young man never forgot.

One night after Saul promoted a package show in Kitchener that featured Duane Eddy and the Rebels and Buddy Holly and the Crickets, Dave and Saul headed back to London and decided to stop to get something to eat. “We pulled into a restaurant along the highway. As we settled into a booth we looked across the restaurant and saw Buddy Holly and his band at another table. We then joined them for an after-show burger,” said Roberts. Shy and nervous, Buddy answered all those who directed questions at him with “Sir,” and it soon struck fifteen-year-old Dave that the singer did not seem to have any idea just how big a star he was.1

By 1958 Johnny Cash had officially joined Columbia Records, for whom he had been recording new songs all summer. Saul watched as the artist took the stage for a show in London. As an onstage presence, Johnny’s enigmatic electricity was unmistakable, and to see him was an experience that far surpassed his recorded material. Though still uncertain of himself, he commanded the stage in a manner that made it hard to look away. Not quite as pretty as Elvis, his dark hair and tall, lithe frame draped in white satin nonetheless cut a striking figure. Possessed of a charismatic darkness, it granted him a depth unlike other artists of his genre. Together with bassist Marshall Grant, with a face as happy and open as a Christmas ham, and guitarist Luther Perkins, eyes askance like a dog that had just eaten his master’s dinner, they painted quite a picture onstage. Though the music wasn’t as nuanced and technically complex as the music Saul typically favoured — the Tennessee Two’s musical abilities were rudimentary, and their stage presence stiff — that signature boom-chicka-boom sound, mixed with Johnny’s rich, unusual baritone, provided a certain warmth he could appreciate. It’s like the Bible, he thought. It does something for some people, and that’s fine. Most important, it was what the kids liked, and they were the ones who would follow Johnny like he was the Pied Piper into Saul’s restaurant.

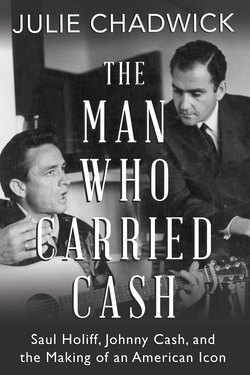

Johnny Cash, backstage in London, Ontario, 1958.

Saul recognized potential when he saw it, and Cash had it in spades.

After the performance, Cash — in a large cowboy hat — kept to himself and glowered the entire time. When introduced to Saul backstage after the show, he “perfunctorily” dismissed him, Saul later recalled. It was a rejection Saul remembered as painful, as he didn’t usually seek out people and had made a special effort for Cash. Apparently the darkness Saul had sensed in the performer wasn’t just an act, and the two “did not hit it off at all.”2

The following year, Saul booked Johnny for a show at the Lucan Memorial Arena. After three twenty-five-minute sets, Johnny prepared to depart to Saul’s restaurant as agreed in the contract, though in this instance Johnny stipulated that his presence not be advertised in advance. Everything proceeded as planned, but before he and Marshall departed for the restaurant, they wanted to discuss finances with Saul, so the three men pushed into the arena’s cramped box office.3

Though it concerned only a trifling amount of cash, a difference in the range of forty dollars, the animosity that had merely simmered during Saul and Johnny’s first encounter erupted into an argument. The two haggled over interpretations regarding Johnny’s contract and whether advertising expenses were to be taken off the top prior to the performer’s cut being calculated (they were). The disagreement irked Saul, who considered himself a principled man who rarely made mistakes when it came to specifics. He was also hard-nosed, and wasn’t about to be pushed around by some young country singer, rising star or not.

Saul fiddled with a cufflink and stared at the men while he collected himself. He couldn’t help but reflect on all the piddling negotiations he had been required to hash out over recent years. The previous summer he had hosted Jerry Lee Lewis at a net loss in London, and two weeks earlier he had promoted hard-drinking honky-tonk singer Faron Young. Laid up for weeks afterward with hepatitis, Saul had been required to phone Young from his hospital bed to explain why the 15 percent non-residence tax for performers — which Young was refusing to pay — was, in fact, a requirement. It had been a dreadful experience; to top it off, Young was both egotistical and “one of the worst shit disturbers” Saul had ever seen in his life.4

Many artists simply had no idea how much sweat went into guaranteeing promotion that went off without a hitch. And that was exactly Saul’s specialty: a smooth, seamless experience that appeared effortless. Despite his better judgment, the complaints and hairsplitting felt like ingratitude.

“You’re just like the rest of them,” he snapped at Johnny, regarding him with something approaching disdain. The comment gave Johnny pause. He prided himself on his distinction from other performers, many of whom he, too, felt were shallow and had a lackadaisical attitude toward music and performing. He didn’t like to think of himself as being like anyone else. Just the week prior, he had announced his departure from the Grand Ole Opry and moved his family across the country to California, in part to pursue a career on the screen, but also to distinguish himself from the rabble in Nashville. He was his own man. The two men regarded each other silently in the stuffy room. Johnny slowly nodded, and then cracked a half-smile. This is a man who stands up for what he believes, Cash mused. Saul felt something shift. Johnny suddenly recognized him as a man in his own right, and an outspoken one at that — a distinct entity rather than just “some passing face in the night.” The two men shook hands.5

“Come as you are & eat in your car,” proclaimed the cube-shaped neon sign as “Old Gray,” Cash’s Cadillac sedan, joined the other Cadillacs and VW Beetles lined up in the drive-in parking lot. After making an appearance, Cash asked if there was somewhere else to eat, so Saul drove him to a nearby steak house, wisely concealing any insult he may have felt.

Finances on the Cash shows had worked well, so Saul negotiated a mid-November tour with Johnny’s new manager, Stew Carnall, for a couple of dates in Kitchener and Peterborough. After the final show in Peterborough, band members Marshall Grant and Luther Perkins were eating at a restaurant with cowboy singer Johnny Western and fiddler Gordon Terry when they noticed a man outside in the bitter cold, pacing beside his Cadillac convertible. Looking exasperated as he approached the restaurant, they realized it was Saul. The door jingled faintly as he came in. After he called a tow truck, Saul approached the table and chatted with the men, who were surprised and pleased at how friendly the promoter’s demeanour was. They began to warm to this city slicker. Stung by their previous encounter and the haggles over finances, Saul had been reluctant to engage with Cash and refused to speak to him for the entire two and a half days, taking care to avoid his dressing room. However, outside of business negotiations, Saul now seemed friendly to the men, even funny. And the shows had been a success, of that there was little doubt — Saul was back in the black, but only barely.6

Once the car was functional again, Saul picked up a friend, real estate magnate Keith Samitt, and the two hit the new 401 expressway to Montreal. As the highway unrolled in the headlights, his mind pored over his finances. The proceeds from the latest shows were a relief; the previous month he had promoted Marty Robbins in a disastrous tour that had sunk him, with more than two thousand dollars in lost revenue. Robbins had, of course, been gracious about the whole affair, and even gone so far as to attempt to adjust the contract so that Saul wouldn’t be out of pocket.

“That Marty Robbins tour didn’t go over so well,” Saul said to Keith, thinking out loud.

“Yeah? But he’s got that big song out, don’t he?”

“‘El Paso.’ I know, I thought it was a safe bet. He’s a good guy, Marty. Luckily, I don’t owe anything, but boy, I lost every liquid nickel on that tour,” said Saul, clenching his jaw and glancing at the speedometer. They were doing at least eighty miles an hour, but the highway was empty. He was broke. He had to think of something. “Marty said he’d arrange something so I could make a few bucks on the next tour. Maybe I oughta take him up on that now.”

He glanced at the car phone, a gadget he adored and used at every available opportunity. It made him feel a bit like Lyndon B. Johnson, who he heard also had a wet bar in his car.

“Hey, Saul. You said these shows you just did went over well. Why don’t you just get some more dates for Johnny instead?” said Keith.

Saul glanced at him, and then back at the road. Of course. He lifted the phone. “Get me Stew Carnall,” he said, and pressed his foot on the gas.7

Carnall had previously managed Johnny in a partnership with Bob Neal, but had bought him out in the beginning of 1960 and had since taken over full managerial duties. A start-up promoter from southern California, he was a prep-school boy who came from money, drove a brand-new Cadillac convertible, and kept himself busy booking small country packages. Four years earlier, he had come across Johnny’s music while swilling a beer and thumbing through songs on a jukebox and was immediately hooked. Initially, the seeming sophistication of tall, blond Carnall in his fancy shirtsleeves and vest put Johnny and his bandmates on edge; they were accustomed to eating at greasy spoons and setting off firecrackers in hotel rooms. However, after a few tours Carnall gave in and became as wild as they were.8

Carnall’s burgeoning friendship with Cash rose just as Neal’s relationship had begun to cool, and he became more of a central figure, but often in the role of friend and party companion. They had experienced their share of outrageous ideas that were often successful, like the time he booked Cash for New Year’s Eve shows in three different California-based cities — and then chartered a plane to pull it off — but Johnny was also in desperate need of someone reliable. By this point he was non-stop touring, performing almost three hundred shows a year to audiences of thousands. A racetrack junkie, Carnall had convinced Johnny to invest in a racehorse with him they named “Walk the Line,” and though he never managed to place better than third, it seemed that Stew had been spending more time hitting the tracks than he had managing Johnny.9

Saul took note of the slack left behind by Carnall and began to keep tabs on all aspects of Cash’s career and what his management entailed. After he called Stew from his car, both men agreed to work as partners on an eleven-show tour of Ontario in May, the largest Saul had yet organized for Johnny. Everything had to be in place. Though Stew came from money and could cut as impressive a figure as Saul did, he was so accustomed to their haphazard ways — carrying wads of cash in paper bags, showing up for flights only ten minutes before they left, and regularly trashing hotel rooms with paint, axes, and handmade explosives — that the litany of details Saul regaled him with during their negotiations must have both dazzled and irritated him. It may have also made him wonder if his days were numbered.

Johnny Cash, at home in California, circa 1960.

“Please forgive my long-windedness, but I feel that, to avoid any misunderstanding, I should be quite thorough concerning our arrangements,” Saul wrote in a four-page letter to Carnall regarding every nuance of the upcoming tour, from the receptivity of audiences in different areas of the country to the cost, availability, and suitability of venues — factoring in seating capacity and whether multiple shows were required to serve demand — and the price of local radio advertising in various cities, calculated down to the cost per second. In some cases, he averaged out the audience Johnny had drawn the last time he had played in a venue, even if it was years prior, and accounted for that also. “If you will examine the foregoing information you will find that it varies only slightly from your proposition, and that certainly it would make me feel like rolling up my sleeves and making this one helluva promotion,” Saul concluded.10

Johnny Cash. This publicity photo, circa 1958, reads, “Saul Holiff, ‘World’s Greatest Promoter’ Your Friend, Johnny Cash.”

Johnny put a dime in the hockey arena pay phone again and stabbed in the numbers. They were at a date in North Bay, Ontario, and near the end of the tour Saul had organized with Stew. It was May 18, 1961, and a business venture had arisen that couldn’t wait. Once again, Stew was nowhere to be found. Finally, he picked up.

“I’ve been trying to get a hold of you,” said Johnny, shifting his weight from one long leg to the other, uncertain of how to begin. “And I know where you’ve been, you’ve been at the track.” There was a pause. “Now, I know, but we blew off this deal, and it was very important to me,” answered Johnny. He took a breath. “Stew, it’s over.”

In tears, Stew desperately tried to sway him, and handed the phone to his wife, Lorrie Collins, who was eight months pregnant with their first child. It was a cheap move. For years, Johnny had been besotted with Collins, a rock and roll singer with whom he had toured in his early years and performed, along with her brother Larry, on the Los Angeles television show Town Hall Party. Though he was still married to Vivian, Johnny’s infatuation with the teenage Collins had become so intense that, consumed with guilt, he confessed his feelings to fellow musician and long-time touring companion Johnny Western while the two were on a drive in the Mojave Desert. Alarmed, Western implored Cash to consider all that he stood to lose: a burgeoning music career that had just taken flight, and his wife and growing family.

“For God’s sake, Johnny. I know you like Western movies. Well, just like in the Western movies, you gotta ride out into the sunset by yourself on this one,” said Western. “It’ll end your career and your family at the same time, and you’ll be finished.”11

Stew Carnall began to chase Collins himself, and by the time she was seventeen, she had impulsively eloped with thirty-five-year-old Carnall — a scandal they narrowly avoided by adding a couple of years onto her age in media reports and subtracting several from his. Rumours circulated that she had married Carnall to avoid torching Cash’s career, but nonetheless, disaster was averted. This time, however, even Lorrie Collins wasn’t about to sway Cash.

“Get off the damn phone, Lorrie. Stew’s fired, and he’s going to stay fired, and there’s nothing you can do to save his job. It’s over,” Johnny said, and hung up the phone.12

Western, who stood beside Cash as the whole scene unfolded, was secretly pleased. A long-time performer with the king of the cowboys, all-American singer and movie star Gene Autry, Western was most famous for “The Battle of Paladin,” a theme song for the popular television series Have Gun — Will Travel. Fair-haired, husky, and gorgeous, he was also a real-deal cowboy — a guitar-playing, sharpshooting, Old West aficionado who was possessed of a near-photographic ability to recall events. One of his earliest memories was of sitting on an uncle’s horse at eighteen months of age, a feat that flabbergasted his mother when he told her. Unable to drink due to an allergy, Western was often one of the sharpest and most sober-minded of the group, and had kept a keen eye on Saul’s meticulous professionalism for months. At that point Saul was merely handling Cash’s bookings, though his attention to detail was a skill Cash sorely needed.

The extended tour had allowed Saul time to speak more deeply with Johnny about his career and where he felt it was headed. Saul tried to impress on Cash that he truly thought a man of his presence and talent was destined for much larger venues, and his label should be throwing more effort into promoting him as a pop act, not just as a country star. It was a niche category, he said, and country hits were often noticed only when they crossed over into the pop charts. With Cash-composed songs racking up millions in sales in his first four years, and more than a million with “Walk the Line” alone, Cash was destined for bigger things. In Saul’s eyes, that was more than enough reason to start pressuring Columbia Records to deliver.13

It was food for thought. Until that point Johnny had felt pretty happy with his lot, blessed even. Who else had this kind of opportunity — to do what they loved to do and get paid for it? But Saul Holiff’s ideas pushed things to a whole new level. “Think about it, John. Instead of just ballrooms and dance halls around the United States and Canada, you could be aiming at Europe, the Orient,” Saul told him. “And big venues in the U.S. like Carnegie Hall or the Hollywood Bowl. Why not? And that could be just the beginning.”14

The Canadian tour also permitted them time to hit it off on a personal level, as Saul saw it. At one point while the two men talked at length in his car, Cash confessed he was worried about Vivian, who was pregnant with their fourth child. When Saul produced his car phone so that Johnny might call home and ease his mind, the generosity and luxury of it impressed him to no end. This seemed to be a man who made things happen.15

The men may as well have been from different ends of the earth, but the two found they had striking similarities, too. Left desperate by the ravages of the Depression, Johnny’s family had relocated to Dyess, Arkansas, when he was three years old to farm cotton as part of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal program. Beyond the childhood poverty that gave them both a determined edge, both men also grew up in families that had suffered the early and violent loss of a child — Cash’s older brother Jack had died at the age of fourteen when a table saw slashed through his abdomen, a defining incident that haunted Johnny for the rest of his life. Both men had also struggled with overbearing fathers who had belittled and singled them out for harsh reprisals, and to whom they always felt they were a disappointment. A stint in the military shaped both men’s youth, and each had sold goods door-to-door and found early solace and escape in the arts.

Their differences were remarkable, too, and once the tour finished the two continued to correspond regularly via telegrams and letters throughout the summer of 1961, displaying an increasing affection and amusement regarding these contrasts. They began to collaborate on plans for the future, much of which centred around an extensive upcoming tour of eastern Canada, including a sponsored hunting and fishing trip in Newfoundland, and even talked over the particulars of financing Saul to travel to the Far East on a reconnaissance mission so that they might plan a tour — a particularly ambitious prospect Saul had dreamed up. In early June, he jotted off a telegram about his progress on both projects.

STILL HOPEFULLY AWAITING YOUR CALL. IN MEANTIME I CONTACTED HARMON AIR FORCE BASE IN NEWFOUNDLAND TO INVESTIGATE A CUSHIONED GUARANTEE TO HANG OTHER DATES AROUND. […] AWAITING YOUR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS AS TO APPROXIMATE EAST COAST DATES AND NEWFIE PROPOSAL. HAVE ACCUMULATED MUCH INFORMATION ALREADY ON THE FEASIBILITY OF YOUR FAR EAST APPEARANCES. WHATEVER HAPPENS, I REGARD YOU AS ONE OF THE NICEST PEOPLE I KNOW. SAUL HOLIFF.16

As he composed another longer and more detailed letter, which was sent around the same time, Saul took time to express his gratitude for the opportunity Cash had given him; privately, he felt insecure about his capabilities. This was all new territory to him, and he felt a deep-seated need to impress Johnny. “Rest assured that I will put every effort and energy at my disposal into making this tour [of eastern Canada] a success. I feel the arrangements are fair, and I consider it a privilege to work on behalf of you, and appreciate the confidence you have shown in me. You can be sure that whatever the nature of the deals made in each city, they will be made with your best interests in mind,” Saul wrote on July 4. Enclosed within the letter was a bundle of photos of Johnny, that had been snapped at a recent concert in Guelph, and a long list of cities for the eastern tour, complete with the population of each location and when Johnny last played them, if ever. Near the end of his letter, Saul paused. There was something else that had come up that he wanted to address — the mens’ behaviour on the Ontario tour, during which Cash and Gordon Terry, an Alabama fiddler and frequent supporting act, had made prank phone calls.

The way it worked was that the boys would gather around in the hotel room after their show, go through the phone book, and call a random number, no matter what time of the night it was. Disguising his voice, Gordon Terry would then pretend to be a delivery service driver.

“We got a truckload of baby chicks from Bandera, Texas, here,” Gordon would say.

“It’s the middle of the night; I’m not comin’ down there for no baby chicks!” the person on the other end would shout back.

“You’d better come down here, or we’re gonna put these chicks in a taxi cab and send them to your house,” Gordon would reply, at which point the entire room would fall about laughing.

Recalling these events, Saul added a postscript to the letter: “I haven’t yet fully recovered from Gordon Terry’s Negro imitations with the special sound effects courtesy of Johnny Cash, and I don’t think the people who received those calls will ever recover.” His distaste didn’t extend much further than an addendum, but the event may have reminded Saul of his own struggles with anti-Semitism.17

Though he chose to address the issue in a lighthearted manner, Saul privately thought the behaviour of the men while on the road was alarming and distasteful. Hotel-trashing bad boys before it became rock-star fashionable, their tours were notoriously rowdy. Bassist Marshall Grant regularly carried a circular saw with him for shortening the legs of hotel room tables and chairs, and all the men sported holsters and Colt .45s, which they would load with blanks and then use to stage gunfights down the hotel hallways.18

Their pranks ran the gamut from dropping water balloons, eggs, and furniture from hotel balconies to more complex antics, like tying all the doors on a hotel floor together with rope, or painting the doors (or sometimes an entire hotel room) a different colour. On two separate occasions they axed down the wall between their rooms and flushed a cherry bomb down the plumbing — which took out an entire wall of toilets below.

A long-running joke of Marshall Grant’s was to sit at a long diner counter, order a big piece of pie with a mountain of meringue, dig in his fork, and then slam it with his hand to splatter the person next to him. On one early tour, the person next to him happened to be Saul, who was mortified. As they left the diner and returned to the road in two cars, Johnny asked Saul to speed up next to Marshall’s vehicle so that he could lob pies at him. In retaliation, Marshall handed the wheel to another driver and sped past, blasting Saul with a cap-and-ball pistol that he had loaded with baloney. Thoroughly rattled, Saul pulled the car over to the shoulder of the road and asked one of the other passengers to drive. It was like nothing he had ever encountered. If he thought the Paikin family was charmingly unbridled, these men were like wild animals.

“Saul was completely mortified by the deal because that was his territory where we worked those shows: Peterborough, Kitchener, Sudbury. He was so straitlaced, he couldn’t imagine anyone doing that,” remembered Johnny Western. “He’d never seen anything like that. He was used to ladies and gentlemen, and there weren’t any on that tour.”

Saul Holiff, Luther Perkins, Gordon Terry, and Johnny Cash on tour in 1962, having a bite to eat at a roadside diner in San Antonio, Texas.

As he grew closer to Cash, Saul also learned to keep his distance; he began to book himself in at separate hotels and avoided the mayhem backstage by hovering about the box office, where he could keep a keen eye on audience numbers and the night’s takings. The all-cash world of promotions in those days was notorious for rip-offs, an aspect of the business he loathed. In his mind, business dealings were to be undertaken in good faith, and he adhered to a sense of honesty in such negotiations with a near-spiritual reverence. It was the grease that kept the entire machine running.

Two days later, Johnny replied to Saul’s message on letterhead that read, “A Few Very Rural, Badly Phrased But Well Meant Words From Johnny Cash.” Typed across the bottom of each page were the words Singer — Song Writer — Guitar Picker — Cotton Picker. He began by addressing Saul as “Mr. Volatile,” and thanking him for the photos he had included. At that time, Cash’s publicist was a man named Howard Brandy, so he noted that if Saul needed anything in the promotional department, Howard was his man. The points Saul had raised regarding the proposed tour of eastern Canada and Newfoundland were agreeable, continued Cash, and a trip to the Far East to check out the possibility of a tour was also something he was willing to pay for.

In personal news, Johnny wrote that he had just laid the foundation for his new home in the hills near Ojai in California, where he would live with Vivian, still pregnant, and their three little girls. In total, the property was fifteen acres, situated on the lower slopes of a mountain that overlooked a beautiful valley, with room for stables to house bulls for hamburger in the winter, Cash wrote. In a postscript he added, “Gordon went to Las Vegas over the weekend, won $1,000 playing dice. I went to the mountains with a friend and my 30.06 Winchester. We dry-gulched two deer. Had venison all week.”19

Saul swiftly composed a letter in return.

June 12, 1961

Dear Mr. Singer, Song-Writer, Guitar Picker and

Cotton Picker …

You’ve got more titles than an Arabian Sultan, but I think your stationery is terrific! In any event, here are a few very suburban, horribly phrased but terribly confused words from Mr. Volatile.

I appreciate your prompt and thorough answer to my letter of June 4th. I’m glad you liked some of the pictures, and will order the ones you requested, immediately. I’m also very happy to hear that Howard Brandy is doing a good job and have made a note of his address for any contributions to his publicity file. I assume that you are aware of the story in Billboard, on Page 6 of the June 5th issue, concerning your acquiring rights to The Jimmie Rodgers Story. I do hope you will go on to produce it, and if there’s a part for a dissipated, constipated, overweight, over-wrought, oversexed, and overbearing promoter, I’d like to read for it. […]

Sorry to hear you are suffering from laryngitis; I wonder if the venison had anything to do with it. I do hope your illness is short-lived and that it doesn’t force you to cancel your Texas date.

The description of your new home sounds like a Paradise and the fulfillment of a dream. It’s exactly what I would like, only I’m still dreaming.

It’s great to hear of Gordon’s win in Las Vegas. I wonder if he tells you about his losses.… Incidentally, what does “dry-gulched” mean?

Recently when I spoke to you, you mentioned that you were going to Colorado with your father and Merle Travis, and, to quote you, you were “aimin’ to breathe air that ain’t never been breathed before.” I was so intrigued by the thought behind that statement that, while in Toronto, I called the Entertainment Editor of the Toronto Star and he felt as I did, and quoted your remarks in the paper. If you knew what the air is like most of the time in Toronto, you would realize what impact your statement had on those who read it.

Very happy to have received your O.K., plan on meeting Columbia officials in New York next week, and hope to leave for Tokyo around the 5th of July.

Keep well, and good hunting! Your Chicken Pickin’ Friend,

Saul Holiff.

P.S. Have you ever played England, and if not, would you be interested?20

With Carnall out of the picture, Saul had seized the initiative and arranged a flight to New York to meet with Columbia executives in mid-June on Johnny’s behalf. What he and Dave Roberts had discussed was true: country stars had a draw, and at least as comparable an appeal as rock ’n’ roll acts. With Johnny’s charisma and star power, Saul was convinced he needed to be treated as much more of a top-level act. Imploring Cash to also think of himself as a bigger star, he now needed to persuade him that Saul Holiff was the man to take him there. And one way that was going to happen was to build his international presence. Part of the trip to meet with the Columbia executives would be to pressure them to support his idea for a tour for Johnny in Japan. Hell, maybe he could get Elvis to go along, too. Before he left, Saul jotted off a quick telegram.

MEETING COLUMBIA OFFICIALS IN NEW YORK CITY NEXT WEDNESDAY. THEY APPEAR ENTHUSIASTIC AND COOPERATIVE ABOUT ORIENT PROSPECTS BUT HAVE DONE LITTLE TO PLUG YOUR RECORDS THERE IN THE PAST. JOHNNY HORTON “ALASKA” NUMBER SIX IN TOKYO THIS WEEK. IF I HAVE MY WAY YOU TOO WILL BE IN TOP TEN BY THE TIME I’M FINISHED THERE. PLAN TO LEAVE APPROXIMATELY JULY 4 AS VISAS ARE NOW OKAY. MAY I BE OF ANY SERVICE TO YOU WHILE IN NEW YORK? HOPE YOU FEEL BETTER. REGARDS, SAUL.21

The mere mention of Horton in the telegram — he had been one of Johnny’s closest friends — likely stung. Johnny was still reeling from Horton’s fiery death in a car accident just seven months earlier, after a drunk driver plowed into his car. It was Cash who had gone to retrieve his body in Texas, arranged the funeral, and then assisted his grieving wife, Billie Jean Horton, and her three children. Dark-haired, devastatingly beautiful, and a renowned singer in her own right, Billie Jean was now a widow twice over, having previously been married to country legend Hank Williams.

Even worse, Cash was also mired in his own secret revelation that he was in love with Billie Jean, and had been so for months. The three were the best of friends and had often gone fishing and hunting together, and Cash considered Johnny Horton’s character to be of the highest integrity. Billy Jean was not only lovely to look at, but as a veteran of the country music scene, she was also filled with her own convictions, ideas, and humour, and wasn’t afraid to speak up to add them into the conversation. Consumed with grief, the two had grown even closer in the wake of the funeral, where Cash had delivered the eulogy. For months afterward he doted on the devastated Billie Jean, and took her on a three-week shopping excursion to New York, where he had wined and dined her in fine restaurants to lift her appetite and spirits. She soon became like a second wife to Cash, who divided his time between her home in Shreveport and his in Casitas Springs. The affair even went so far that he asked Billie Jean to marry him, though his spiralling dependence on pep pills and his marriage to Vivian finally gave her pause.22

First introduced to him by Gordon Terry in 1957, the pills — amphetamines with the trade names of Dexamyl, Benzedrine, and Dexedrine — were often used on tour to help musicians endure the endless hours of driving through the night to get from show to show. “You know, I think some of these promoters would get a map of North America and just throw darts, and wherever the dart hits, that’s where you’re gonna go next. With a thousand miles between concerts,” Cash once mused.23

Even Johnny Western, who largely abstained from drugs and alcohol, had to admit that the use of amphetamines had likely saved their lives more than once by preventing drivers from falling asleep at the wheel. Johnny discovered they had another use — they electrified his performances and eliminated his shyness onstage. However, the drying affects of amphetamines could also wreak havoc on his voice. And as much as they pumped him up, they began to twist his personality. As he began to consume more, he would be awake all night, pacing and nervous or brooding and moody. He would have deep, insightful conversations in which he was very much lucid and present, but would then forget them the following day. At times it was like there were two people inhabiting his body.24

To cope with the stress of Horton’s death, Cash had begun to turn more and more to pep pills, though the truth was that it was these pills that caused him to act strangely about Horton’s death, not the other way around. Whatever the case, the drugs were more than likely the culprit that had caused Johnny’s laryngitis, rather than the venison Saul had joked about.

If Saul was aware of the pills at this point, it wasn’t a primary concern. For now, foremost in his strategy was the need to convince the officials at Columbia that Johnny was worth further investment. Just prior to Saul’s departure, Cash jotted off a letter to advise him about who to look out for — namely, people who had been kind to him: Debbie Ishlon, head of public relations, Dave Kapralik, Peter Freund, Bill Gallagher, and Columbia president Goddard Lieberson, whom Cash referred to as “The Great White Father.” If there were any problems, Cash added, he could be contacted on the road care of “the leading motel” in Eureka, California. With that out of the way, Cash added that though he was feeling a lot better, the smog in Encino was burning all of their eyes out. “Can’t wait to get into the new place, and out of it,” Cash signed off.25

It was a short trip to the Columbia offices, and upon his return Saul excitedly filled Cash in on what had transpired. “Just returned from New York last night; met Gallagher, Kapralik and many others. They erroneously thought I was your manager, and although I emphasized that I’m not, they all appeared to be happy about the recent change and felt that I might be an influence for the good. I only hope that they are right,” Saul wrote on June 23. “Bill Gallagher tells me that you wrote a song especially for him, and he was as pleased as punch about it. Kapralik is now the main cog under Lieberson.”

He had pressed the men on the importance of solid promotional materials to back up some of Cash’s upcoming U.S. performances and then engaged them in a discussion about various details of publicity, including a plan to increase the frequency with which his singles were played in jukeboxes. This in particular was significant, as Saul’s own first exposure to Cash had come via jukebox.

“They all think you’re great, and send their best regards,” Saul concluded. “I can’t get over how prompt you are in replying, and the fact that you are pounding out letters left and right. I mentioned this in New York and they think you have been reborn. All kidding aside, I do appreciate the business-like way you’ve attended to my requests. Keep up the good work; it’s bound to be worthwhile.”

He thought for a moment, and then included a postscript: “Still don’t know what the hell ‘dry-gulched’ means!”

Things had gone even better than expected at Columbia, and though Saul’s inexperience had made him nervous, the brass there had treated him with respect, even going so far as to express how pleased they were that Cash appeared to be in solid hands.

Following Carnall’s departure, however, Cash’s management situation had in fact gone from bad to worse. Though Carnall was still booking some dates, in the absence of his other duties, Cash had decided to manage himself. Upon their return home from Canada in the spring, Johnny Western had walked to Cash’s Los Angeles office to find him answering the phone and booking his own shows. Knowing Cash was never much of a businessman, even at the best of times, Western decided it had gone far enough. In the months leading up to Stew’s firing, Western had been gunning for Johnny to go with Saul, and told Johnny the promoter had already offered him more management on the road than he was paying Stew Carnall or Bob Neal to do.

“I’m seeing stuff — the t’s are crossed, the i’s are dotted, all the ducks are in a row,” Western said. “And he’s just booking your shows — he’s not managing you and he’s not picking up 15 or 20 percent. This is incredible. You need to either get Saul or get someone exactly like him.”

However, Cash had ignored Western’s advice and was now facing disaster. Even Carnall had been better than no manager at all. If Cash wouldn’t approach Saul, perhaps Saul would step in of his own accord. Desperate, Western sat down and composed a letter.26

July 1, 1961

Dear Saul,

Many thanks for your nice letter of June 16.

I have meant to bundle up some things and send them on to you for some weeks now and have either been busy or have done the typically American thing and “put it off until tomorrow.” The package of records enclosed are releases of mine that I wanted you to have for your personal record collection. I’ll have another for you before you return from the Orient as my new record of “Paladin” will he released very shortly.

Enclosed also are the photos and bios for the next tour. I’m really looking forward to working with you again, Saul. I hope on this next trip that you can reach some sort of management thing with Johnny as he is wandering in a fog, so to speak, now.

He is trying to keep his business affairs together and is also booking himself, neither of which is even a little bit successful. He is not a good businessman nor can he, or should he, be on the phone when the bookers call for a Cash show. He is in serious need of expert advice on what to record and what to release, Saul, and if ever there was a big star on the brink of disaster, it’s Johnny right now unless he has some qualified help immediately. He has a new publicity outfit that is doing great things for him and doesn’t have so much as a liaison man between himself and this office. I personally feel, Saul, that when you return from this trip that you should lay your cards on the table with John and at least offer a management deal as whether he takes it or not, he needs you.

I may have stepped out of line where Johnny is concerned in the above paragraph, however I feel that it is in his very best interest that I made mention of this need. You’ll have to take it from there.

Till I see you again then, I remain

Gratefully, your friend,

Johnny Western.27

It was just the catalyst Saul needed, and only confirmed the impression that he was on the right track. The same day, Cash responded to an idea Saul had passed by him. Always mulling over what new directions he could take Cash, Saul had a vision of broadening the show in a more established sense. Cash often travelled with Johnny Western and Gordon Terry, and had shared the bill with other star performers like Merle Travis, but Saul wanted something bigger — a sort of travelling country extravaganza. Most important, he wanted a woman up front with Johnny to add chemistry. The perfect time to launch this would be on their eastern Canada tour, and the most likely candidates were Bob Luman, a country singer-songwriter from Texas, and Rose Maddox, a powerful vocalist who started out performing with her brothers and had successfully moved on to a solo career. She had toured with Cash on shows before and was a solid performer who gave it her all onstage, with glittering costumes made by a bona fide rodeo tailor and finished off with white rhinestone cowboy boots.28

After completing a mid-June tour in Lubbock, San Antonio, and El Paso, Johnny settled into his bed late one night and scrawled out a handwritten response to Saul’s letter about his trip to New York. “Glad the ‘wheels’ at Columbia were kind. Don’t repeat it, but I’ll be damned if I remember writing a song for Bill Gallagher,” he wrote by way of introduction, and then addressed the issue of Bob Luman and Rose Maddox, which revealed where his true allegiance now lay — and it was not with Stew Carnall. Prefacing his words by saying they were “STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL,” Cash said he had asked Carnall how he might get in touch with Bob and Rose for booking purposes, to which Carnall responded, “Why not let me sell them to Holiff so I can make a commission?” Cash agreed. This was where his warning came in.

“HINT #1: (TOP SECRET),” Cash wrote to Saul. “I never paid Rose Maddox more than $150 per day, and usually $125 per day and she was constantly available. HINT #2: (TOP SECRET) Bob Luman has never worked a tour with anyone but me, and we paid him $150 to $200 per day.”

Most important, Cash added, was that “Stew will try to ‘snow’ you.”

As he nodded off, Cash wrote that he would be travelling to Anchorage, Alaska, on July 6 and then be off bear hunting, before telling Saul that to “dry-gulch” meant to sneak into the mountains and kill deer, out of season.29

Though not yet officially Johnny’s manager, the letter’s advisory illustrated a clear and crucial shift in Johnny’s loyalties, and Saul didn’t miss a beat.

“Appreciate your ‘top secret’ and confidential hints regarding Luman and Maddox, which will remain confidential as you requested,” Saul responded on July 2. “I won’t do anything definite about extra talent until I’ve investigated and made sure that they would be the right people and would prove helpful. It may be that Rose Maddox or someone along the same lines would prove sufficient to give the show more depth and avoid too much in the way of extra cost.”30

On July 11, Saul departed for Japan and managed to secure some connections for what he envisioned as a series of one-nighters in the Philippines, Singapore, and Japan, which he hoped could be scheduled for that November. As he kept the Far East pan warm in the fire, he struggled to finalize the last dates for the tour of eastern Canada and Newfoundland (which was in the midst of a wildfire outbreak that had raged for weeks). Saul was frustrated by the lack of progress. As the heat of summer bore down, both men then also became entangled in intense life circumstances that grappled for their attention.

In mid-August, Saul received news that his father had died, just months after the family had been rocked by the sudden death of Sam Paikin. Only fifty-one, Sam had suffered a heart attack while playing golf at the Beverly Golf and Country Club in Hamilton. Two days later, as the family was forced to carry on with the first birthday party for Sam’s grandson, Steve, Saul’s sister Ann was in a daze. Within a month, she sold their house and moved into an apartment. The blow to her identity as “Mrs. Paikin” was severe. Saul said very little to anyone about either death, simply writing to Johnny that his father had passed away and “as you can well appreciate, it has somewhat upset my working tempo,” though the loss of both his father and mentor must have cut him deeply.

Saul also inquired after Johnny’s wife, Vivian, who had given birth to their fourth child, Tara, on August 24. Johnny saw the new baby only briefly before he hit the road to play a weekend show at the Indiana State Fair in Indianapolis. The tension among the needs of his expanding family, his passion for other women, like Billie Jean Horton, and his burgeoning career was beginning to overwhelm him. “Hi Saul, am rushing, getting junk taken care of so I can leave for Indianapolis,” Johnny scribbled a week after the birth, and reassured him that both Vivian and baby Tara were fine. Though earlier Johnny had expressed to Saul that he couldn’t wait to get away from the smog and into his sprawling new home in Casitas Springs, in reality the family had scarcely moved their belongings into their opulent new house before Johnny had disappeared again on tour.31

Sensing the strain Johnny was now under with four young children at home, Saul continued to write to ask about Vivian and his domestic life, mailing trinkets for the older siblings and a silver dollar memento to commemorate Tara’s birth. “I re-read your autobiography last night,” Saul wrote to Johnny on September 4, after he had confirmed that all the dates for the Newfoundland tour were finally set. “It is much more revealing than I first realized, and certainly provides a clear insight of the many stages that you have passed through up ’til now. I believe that any time you get dejected or despondent you should re-read it yourself.”32

The twenty-one-day tour of eastern Canada and Newfoundland was sponsored by Field & Stream magazine and included a multi-day moose hunting trip, during which photographer Richard Fiske snapped au naturel photos of Johnny in prime hunting territory, engaged in one of his favourite pastimes. In advance of the tour, Saul and Johnny stopped over in New York on October 3, where they met with Columbia executives to renegotiate Johnny’s contract. Just prior to their departure, Saul organized a quick show at Massey Hall that met with middling reviews. The show was sold out three days in advance and more than a thousand people were turned away at the door, but the next day’s newspaper declared the show to be a “Big Letdown.” The incessant upselling of merchandise, constant assurances that they were going to have “a good show” by emcee Johnny Western, and syrupy praise of Canada throughout the performance was frankly insulting, said Toronto Daily Star reviewer Wendy Michener.33

“Mr. Cash himself did not appear until the end of the evening’s program of popularized folk and western music, and then for only half an hour,” she wrote. “A cold, or throat trouble of some sort took the resonance out of his low-pitched voice, and the zip out of his performance. Those rhymed stories of his, so reminiscent of Robert Service, were falling apart at the seams despite good support from his trio.” The greatest portion of her praise was reserved for the Tennessee Three, Gordon Terry — “spectacularly dressed in white with rhinestones” — and Rose Maddox, who, Michener felt, delivered the “meatiest” performance with “lots of real singing and little chin-wagging.”34

There was that throat trouble again. It was becoming a problem, but Saul didn’t have time to consider the implications, and if he did, it still seemed like Cash had a handle on it. No, he had to focus. The return trip to Columbia Records was to be a trial by fire of sorts, his chance to show not only the executives there — but also Johnny — that he truly meant business.

I’m like a mystery guest. I’m a completely unknown entity, Saul thought, as they entered Columbia president Goddard Lieberson’s office. Everything seemed to slow down, as though he could observe the proceedings from outside himself. An aristocrat and consummate classical music fan, Lieberson not only cut an elegant figure himself but also was married to a stunning Norwegian ballerina dancer of considerable fame. It was intimidating, but Saul had at least one card he could play, and it was that he knew Lieberson either possessed or pretended to have great personal interest in Johnny. Arguably one of the most influential and powerful men in the recording industry, it was British-born Lieberson’s visionary nature that led the label to sign Johnny in 1958. Under his leadership, the company had doubled their sales. But he was much more than just a suit. An accomplished composer, he had written more than a hundred pieces of music, and was also a pianist, producer, and novelist. To Goddard Lieberson, I must be the equivalent of an irritating mosquito, Saul mused.35

It was there, feeling completely out of place in Lieberson’s spacious office, his heart racing, that Saul had a moment of realization: it was then, right then, that he needed to assert himself. It’s now or never, he thought. He made his move.

“You’re just going through the motions,” he declared. “Actions speak louder than words, and so far it’s all words. You don’t appreciate your talent. You’re not doing what can be done for him.”

At that, Lieberson stood up, stormed out of the room, and didn’t return.

At that moment, Saul felt his relationship to Johnny become an actual reality. “I think he realized that I was either one of the world’s best actors from a small town that ever existed, or else I rose to the occasion. I never dreamed I could, but I made my point. I got him sufficiently upset. The renegotiation took place,” he later told author Michael Streissguth.36

This renegotiation included a push from Saul for a new arrangement in which Cash’s records would no longer be selected in Nashville, but in New York by Mitch Miller, Columbia’s influential head of Artists and Repertoire in their pop division. How a musician was categorized was critical, and if Johnny remained pigeonholed in the Nashville country genre he would never get the radio play he needed and therefore never become as big a star as Saul envisioned. The move to New York would mean that his songs would then be largely chosen for their pop appeal.

On Thursday morning, Saul and Johnny left New York to fly into Halifax for the tour in eastern Canada, a trip that though neither of them yet knew it, would prove crucial to both of their careers.37

It was Johnny’s first time in Newfoundland, and he brought Johnny Western, Merle Travis, and Rose Maddox, among others, along for the trip. Both Johnny and Saul had grown fond of Maddox, who had travelled with them both in their plane to New York and on to Newfoundland. Convincing Maddox to come on the trip had taken some work — on September 29, en route to meet Cash for a show in Boston, the landing gear on Maddox’s plane had failed and sent the aircraft into Boston Harbor. She had escaped unhurt, but the accident had rattled her, and she became terrified to fly afterward, though the rest of the troupe had pitched in to comfort her. Cash took her shopping to replace her stage clothes, and she went to sleep each night in Cash’s pajama bottoms and Johnny Western’s pajama top.

There was another issue, however, which was that she thought Saul might have an amorous interest in her. Cash had only recently left his last manager, and if this was true she didn’t want to cause any trouble in his venture with a new promoter. Feeling protective, Cash had coaxed her into facing her fears and all but pushed her onto the plane, where she reluctantly agreed to travel with the two men. This concern displayed by Cash seemed to offset any attraction Saul had toward her, she later said, though it’s not clear whether it was real or imagined.38

Upon their arrival, the group settled into a cabin in Gander, and played all the venues they could in the province, from fishing villages to the Harmon Air Force Base in Stephenville. It was well after midnight when the latter show wrapped up and the troupe emerged from the base, jazzed from the show and not the least bit tired. The boys piled into their car outside the venue and turned on the radio. Jimmy Dean’s new single “Big Bad John” came on, and they all looked at each other. It was the first time any of them had heard it. “That’s going to be a smash hit,” mused Johnny Western. “It’s going to be a monster.”39

When not playing shows, much of their time was spent holed up in the cabin, sharing stories, drinking, and taking drugs. Merle Travis favoured barbiturates, and downed so many pills it could have “knock[ed] an elephant to its knees,” remembered Western. “He was barely able to perform, but he was still up there.”

Saul did his best to hang out with the other guys, though trampling through the bushes with high-powered rifles was not something he was accustomed to, nor had much interest in. He had never fired any kind of gun in his life outside of the military, and when his turn came, the rifle’s recoil bashed him in the forehead with such force it left a scar. The effort eventually paid off for Cash, who bagged a moose and then excitedly communicated the news to Merle Travis through the walkie-talkies that were a sponsored feature of the trip. The show dates were not always ideal in crowd turnouts, but they were ticking along nicely when their first setback of the tour occurred.40

Vivian, home alone in the mountains with her new baby and three young girls, called Johnny in a panic.

“He owned the whole side of a mountain and his friend Curly Lewis had built this beautiful home up there, but it backed up to this hillside and there were rattlesnakes all over the place up there,” said Western. “These rattlesnakes were coming down into the yard, and of course with the four little girls there everybody was petrified. Vivian was just scared to death of snakes and so were the kids, and they were real live rattlesnakes, in the backyard. She just said, ‘I can’t be with this.’”

Johnny, who had a phobia of snakes, immediately boarded a flight from Corner Brook, Newfoundland, to Los Angeles and tossed a promise to Saul over his shoulder that he would return for the second half of the tour, no matter what. Four days later, true to his word, he did return, and he made an overture that formalized an idea that had been on both men’s minds since their meeting at Columbia.41

Not long after he disembarked from the plane, Johnny called Saul over and told him he had something he wanted to discuss. In his hand was a pad of coffee-stained, yellow, legal-sized stationery. Scribbled out on the paper was the outline of a management deal. Johnny then asked Saul to be his manager, and Saul agreed. They negotiated that Saul was to receive 15 percent commission on all income that Johnny earned, from one-night shows to record royalties, and that all of Saul’s road expenses would be taken care of. Then they shook hands.42

It was a significant move that — though executed casually — would come to characterize and define the men’s relationship and lives for the next decade to come.