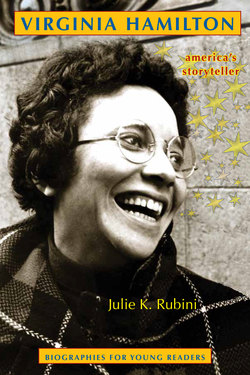

Читать книгу Virginia Hamilton - Julie K. Rubini - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TWO

SETTING

My subject matter is derived from the intimate and shared place of the hometown and the hometown’s people.*

IF VIRGINIA’S family provided the foundation for storytelling she became known for, Yellow Springs provided the backdrop for her tales.

Yellow Springs was the place where little Virginia ran home on the last day of the school year, very excited. In her small hands was a prized possession, a book. It was bright and shiny, with three cute yellow ducks on the cover. She’d won it as a result of having read the most books in her class.

It was Virginia’s first award, and treasured. New books were hard to come by in her family.1

Virginia loved to read.

Yellow Springs was the place with the quaint library that nurtured Virginia’s passion. “It was a lovely little cottage,” Virginia recalled, “shaped like a gingerbread house and made of gray fieldstone, with a red tile roof.”2

YELLOW SPRINGS LIBRARY DURING VIRGINIA’S CHILDHOOD

Photo courtesy of Antiochiana, Antioch College

Her love for the Yellow Springs Library began with a quest to find out more about an exotic breed of chicken her mother had sent away for.

Virginia’s mother encouraged her to “look at the rainbow layers” of the eggs from their Araucanas chickens. While the chickens roamed about in the yard, Virginia explored the henhouse.

She discovered the nests held eggs of a variety of colors. Her mother’s exotic chickens laid eggs that were turquoise, pink, olive green, and various shades of brown.

“When I told my class at school about my job as colored-egg gatherer, some of the town kids snickered, ‘Both you and the eggs are colored!’”

“I told Mama and she said, ‘Go take a look in the library.’”

“‘For what?’” I wanted to know,” Virginia said.

“‘For the rainbow layers,’ Mama said. ‘There’s more than one kind of chick with color. More than Araucanas.’ And then she gave me what I thought of as a secret smile.”3

And so it was that Virginia became a regular visitor to the local library.

She even thought the “spritely, bright-eyed” Story Lady lived at the library. Once a week the Story Lady visited Virginia and her classmates in elementary school. She walked them across the street and introduced the children to her world of books.

“I’d get side-swiped every time by all those straight-back sentinels in long still rows,” said Virginia. “Short books and tall books, blue books and green books. What’s in them? I would wonder. They had more colors than the rainbow-egg layers ever thought of. And a greater supply of subjects. Today I realize that was my mother’s point. Get Virginia to the library and she will find out many things.”4

Yellow Springs was the place where Virginia roamed freely and played in the surrounding fields and farms owned by her family. She ventured beyond her family’s lands and on to the other side of town and the glen, now known as Glen Helen, a thousand-acre preserve.

“In the glen I discovered deer, the sweet and yellow freshwater springs, an immense, condemned pavilion once a grand hotel and marvelous old vines strong enough to swing on.”5

The images stuck in Virginia’s mind and came out in two of her works. The House of Dies Drear features an old, spooky house, and the swinging vines appear in M. C. Higgins, the Great.

Through the same lands that Virginia ran as a child, Native American children had run years before. The Native Americans laughed and played as she did, chasing shadows in the woods, and picking wildflowers to take home to their mothers.

These same lands were where white settlers hunted and welcomed Ohio into the Union in 1803.

Ohio outlawed slavery in its 1803 Constitution.

However, the legislature passed “Black Laws” that discouraged migration to the state.6 The laws were intended to make life so miserable for African Americans that they would not use the new free state as a refuge from slavery. Blacks coming into Ohio were required to show a certificate of freedom. Those who already lived in the state had to register with a county clerk. African Americans living in Ohio could not work in the state unless they possessed the freedom certificate. There was also a state fugitive law that allowed slave owners from other states to come into Ohio and capture their former slaves without interference.7

But, despite the restrictions, many slaves found freedom traveling via the Ohio River and settling in the area.8 Yellow Springs was the place where many African American families bought property and built their homes.

Early residents of color may have been encouraged by the fact that Horace Mann, Antioch College’s first president, was in favor of eliminating slavery.

So it came to be that Virginia’s relatives, the Perrys and the Hamiltons, established their farms here.

Yellow Springs was the place where Virginia first experienced racism.

Virginia grew up surrounded by her extended family, comfortable in their presence, unaware of the division that existed.

Along with playing all day in summer, Virginia and her cousin Marlene became young entrepreneurs. They picked berries in the morning and sold them along the roadside, earning money to catch a movie at the Little Theatre.

The Little Theatre, now known as the Little Art Theatre, sits on Xenia Avenue, just a hop, skip, and a jump from the library. Marlene and Virginia rode their bikes the five-minute trip up to the theater, the smell of popcorn luring them in. Imagine their excitement at seeing movies on the theater’s big screen. When Virginia first started going to the theater as a younger child, she and Marlene were not free to choose just any seat. They had to sit in the back two rows of the theater.

Only whites were allowed in the front.

In 1942, when Virginia was eight years old, that changed.

THE LITTLE THEATRE IN YELLOW SPRINGS

Photo courtesy of Antiochiana, Antioch College

The new owners of the town newspaper, the Yellow Springs News, Ernest and Elizabeth Morgan, ran an editorial about the separation of blacks and whites in the town. “We all know that much discrimination is practiced in Yellow Springs. The theatre, restaurants, even the Churches, find themselves doing it.”9

The editorial hoped that this could change through “steady education” and in a “friendly way.”

Students from Antioch College and faculty from Wilberforce, the first private African American college in the United States, staged a creative and peaceful approach to eliminate the segregated seating in the Little Theatre.

The students arrived thirty minutes early for a movie. The black students sat in the section designated for blacks. The white students sat as they normally would. Then slowly, black students moved to the white section. Whites went to the back and sat.

. . .

CHILDREN AND THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

CHILDREN AND young people played an important role in the civil rights movement. In early May of 1963, hundreds of students of all ages marched in Birmingham, Alabama. They wanted to end the segregation that existed in their city. Children and their families could only go to fairgrounds on “colored days.” They weren’t allowed to visit city parks, which they supported with their taxes. Blacks had to use separate restrooms, fitting rooms, and even drinking fountains. Young people marched and rallied against this separation and inequality. Police responded by taking protesters, some as young as nine years old, to jail. Firemen used high-pressure water hoses to try to disperse the crowds. And, in a very famous image, police dogs attacked a seventeen-year-old who defied the anti-parade ordinance the city had enacted. The image landed on the front page of the New York Times. This photograph and reports of the violence concerned the president of the United States, John F. Kennedy. Ultimately, through negotiations, the city agreed to desegregate lunch counters, restrooms, fitting rooms, and drinking fountains. Children helped make a difference.10

. . .

The owner was overwhelmed with the shifting of students, and couldn’t do anything about all of the patrons moving about.

The owner complained to the mayor, the police department, and, even, a county judge. But the city officials would not do anything about the situation because no laws were broken.

The owner took down the rope that separated the blacks in the back from the whites in the front.

VIRGINIA (SECOND FROM THE BACK) AS A YOUNG WOMAN OUT WITH HER COUSINS

© 2016 The Arnold Adoff Revocable Living Trust

From that point on, Virginia and Marlene could watch movies in the theater wherever they wanted.

The town of Yellow Springs is where Virginia was formally educated. Virginia was one of only a few black students through her early school years. Her older siblings, including sisters Barbara and Nina, and brothers Buster and Billie, preceded her in the Yellow Springs school system. So too did her cousins. But otherwise, there were few African American children at the schools.

When she began attending Bryan High School, hers was the only non-white face smiling from pictures of the cheerleading squad.

Virginia did not seem to be troubled by this. She just always tried to do her best.

“If our white classmates were proper, then we were more so,” Virginia later wrote. “If they were bright, we felt we had to be smarter, and often we were smarter and we were proud of ourselves for showing that we were as good as they were. But, oh, how terrible for children to always have to think this way. What an awful toll it took on our spontaneity.”11

VIRGINIA RECEIVES RECOGNITION FOR A SPEECH CONTEST

© 2016 The Arnold Adoff Revocable Living Trust

Virginia was a good student, obeying one of the few rules her mother had, to stay on the honor roll. She played basketball, had a number of friends, and often got together with her cousins for fun.

She was writing and participating in speech contests, too. And she was being recognized for her efforts.

. . .

THE OHIO CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1959

THE SIGN stating “We cater to White Trade Only” hung in the window of a restaurant in Lancaster, Ohio, in 1939. The peaceful protest at the Little Theatre by the students and faculty from Wilberforce and Antioch Colleges happened in 1942. Yet, a law that prohibited discriminating against people of other races in public facilities was passed years before, in 1884. The law was not very effective in private businesses. The Ohio General Assembly enacted the Ohio Civil Rights Act of 1959. Along with eliminating discrimination in employment, the act also guaranteed all persons access to public facilities and private businesses.

SIGN ON A RESTAURANT IN LANCASTER, OHIO

Photographer: Ben Shahn. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, reproduction number LC-USF33-6392-M4

. . .

But high school accolades were one thing. Where would Virginia’s passion for writing take her?

The answer was literally right up the road.

But it wasn’t an easy path getting there.

DID YOU KNOW?

The United States Government did not pass the Civil Rights Act until 1964, five years after Ohio passed its legislation.