Читать книгу Virginia Hamilton - Julie K. Rubini - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER THREE

PLOT TWIST

I remember one time telling my older sister that I was going to be a famous writer someday; and of all the responses she could have given, she said, “Oh goody, then I’ll be famous too.”*

VIRGINIA’S PATH to becoming that famous writer began just over a mile away from her home.

At the end of a long day working in the Tearoom at Antioch, Virginia’s father would share stories of the students he served and had discussions with. When she was in high school, Virginia began working with her father at the Tearoom. Here she met students from all around the country. Many of them were from New York City and told stories of what they loved and missed about the big city.

Both young men and women made their way to classes under the shadow of the twin bell towers on the campus of Antioch College. Black and white students mingled on the grounds of the college, sharing ideas and studying together. Not only was Antioch the first college to offer equal opportunities to both young men and women, it was also among the first to offer the same to African Americans.

Through her experiences while working in the Tearoom, Virginia began dreaming of going to Antioch. She hoped to study writing and, perhaps, become that famous author by moving to New York City. It was a big dream. Her parents could not afford the tuition at the private college. As the top graduating student at Bryan High School, she should have received a scholarship to Antioch.

But she didn’t.

The head of the theater arts program at Antioch, Paul Treichler, and his wife, Jessie, were friends of the Hamiltons. The Treichlers did not feel it was right that Virginia did not receive a scholarship. So they intervened. Mrs. Treichler contacted the Jessie Smith Noyes Foundation on Virginia’s behalf.

The foundation was created in 1947 by Charles Noyes in memory of his wife, Jessie. Jessie was as beautiful inside as she was on the outside. She was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1885, the same year the world’s first skyscraper was built in Chicago. Skyscrapers would play a role later in her life, as her husband, Charles, bought and sold them in New York City. One of his most famous real estate deals was selling the Empire State Building in 1951 when it was considered a “white elephant,” or a building too expensive to maintain.

Jessie devoted much of her life to helping others. She was a leader with the Brooklyn YWCA, one of the first in the country. Through the YWCA, Jessie worked to eliminate religious intolerance and promoted equality for women and for all races.

Jessie died in 1936, just two years after Virginia was born.

Charles created the Jessie Smith Noyes Foundation to promote equal education opportunities for all, a policy Jessie believed in. A scholarship program was established to assist students in financial need. Mr. Noyes determined that half of the scholarships would go to black students.

Thanks to the help of Mrs. Treichler, one of those students was Virginia Hamilton.

Virginia, the scholar, was on her way. She enrolled as a writing major at Antioch College.

ANTIOCH COLLEGE TOWERS

Photo courtesy of Antiochiana, Antioch College

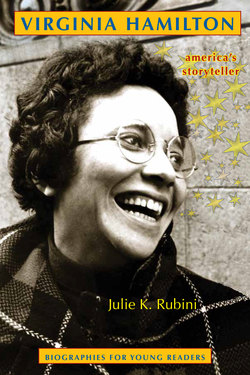

VIRGINIA AS A YOUNG COLLEGE STUDENT IN OHIO

© 2016 The Arnold Adoff Revocable Living Trust

Virginia began to develop her unique writing style under the guidance of her professors, including Nolan Miller, who taught creative writing courses at Antioch for over fifty years. Mr. Miller wrote many short stories and had several novels published during this time. Classmate Janet Schuetz would also be of influence later in Virginia’s path to being published.

Virginia and her fellow writers at Antioch often hung out with their little portable typewriters at a small coffee shop off Route 68 in Yellow Springs, crafting their stories.

After three years of study at Antioch, she transferred to the Ohio State University in Columbus as a literature major in 1956. It was there that a professor suggested she follow her dream of moving to New York City to pursue her writing career.1 So later that year, Virginia packed her bags and left Yellow Springs, which she considered “a dead end for me. And boring. No men. Just cousins!”2 “I left Yellow Springs to seek my fortune in the big city,” Virginia said.3

Virginia wanted to strike out on her own, away from people who were trying to help her on her journey. Even though she appreciated their assistance, Virginia determined that the best way to move forward in discovering her own voice was to leave those she loved behind. She felt compelled to move to where she might be surrounded by writers and artists. Virginia longed for independence.

Virginia moved to the East Village of New York City, known then as the Lower East Side. She found herself living in a melting pot filled with people of Polish, Czech, and Yugoslavian descent. The streets were also filled with Eastern European Jews in their wide-brimmed hats. No one really spoke to each other. Everyone seemed to isolate themselves from one another.

In leaving her home in Yellow Springs, she left the comfort of nearby family and friends. She left the ability to roam barefoot around the fields, to hear the chirping of the crickets, and to see the dance of the fireflies.

What she initially found in New York City were noisy cabs honking their horns; the fumes from busses choking the air; and people bumping into each other on the streets, their hats casting a shadow over their eyes.

Virginia felt a bit more at home when she would go visit the Hudson River on Sunday afternoons. “My river changes uptown. It has Riverside Park along its steep banks, and the park is beautiful, full of children and dogs. All sorts of people rest, lounge, read their papers, and sing. They all needed the river the same way I did.”

The river helped Virginia transition into her new home. Her writing improved, as she separated herself from all that was familiar to her. “My writing grew better as I grew older inside. I came to understand that the river’s flow was the flow of freedom within all of us.”4

Along with adjusting emotionally, Virginia also had to make her own way financially.

She paid the rent on her Second Street apartment by working a variety of jobs. She drew upon her many talents and her ingenuity to make her way. Virginia used her awareness of fabrics and her typing skills in her job as receptionist and guide at the Cooper Union Textile Museum. The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art was established in 1859. Located just blocks from Virginia’s apartment, the college continues to offer an education in art, education, and architectural engineering.

The position with Cooper Union didn’t pay enough money to cover her rent, so Virginia learned a new skill to help make ends meet.

Virginia went to a used bookstore on the East Side and purchased an accounting book. She taught herself accounting and got a job working for an architectural firm to pay for her living expenses.5

Still shy of funds to support herself in the big city, Virginia turned to a talent she had enjoyed since childhood. Singing.

The Saint Nicholas Ballroom on the Upper West Side hired Virginia to sing at night. She used her strong, deep voice as she sang with big bands, as a soloist as well as with groups.

Gradually, Virginia eased into the bohemian feel of the big city. And she looked the part. She went about the city wearing a black beret, a dark trench coat, and velvet slacks. “I thought of myself as a young sophisticate developing into an artist,” she said.6

Virginia loved jazz music and befriended many musicians and singers through her own singing gigs. She enjoyed going to different clubs and listening to the musicians wailing on their saxophones, jamming on bass, and working their magic on the piano.

One particular club, the Five Spot Café in lower Manhattan, was a favorite. The Five Spot was just a ten-minute walk away from Virginia’s apartment on Second Street.

“It was a time of cool jazz and ‘shades’ worn at night,” Virginia said.

Virginia fit in with the hip crowd as she sat back in her seat, relaxed while listening to jazz at the Five Spot Café. She tucked a book under one arm and sipped her drink slowly. The audience didn’t applaud after a song. They snapped their fingers to show their appreciation. Virginia did the same.

One such sophisticated evening at the Five Spot changed her life.