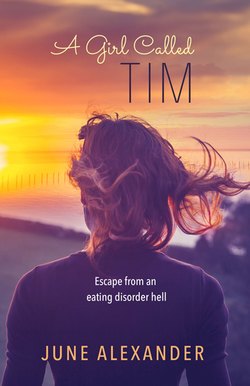

Читать книгу A Girl Called Tim - June Alexander - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2. MY ILLNESS DEEPENS

ОглавлениеGlobules of fat on the meat chunks peered out of the lamb stew, daring me to eat them. It didn’t help that the stew’s rich brown gravy had merged with its companion—a large blob of white-as-snow potato mashed with generous lashings of creamy milk and butter. For the first time in months I had looked forward to sitting down to tea. Tonight Mum wouldn’t have cause to growl. But, confronted by the lamb stew and potato, guilt set in.

I loaded my fork, and could go no further. The fatty globs glared at me. I skirted them, eating the boiled carrot and cabbage, carefully avoiding the bits that touched the stew and mashed potato.

Mum grumbled. ‘Wasteful,’ she muttered, taking my plate away. Then she served steamed apple pudding with a rich custard sauce poured over top. This dessert, once my favourite, now sparked terror.

‘For goodness sake, eat!’ Mum begged. The pudding was one of Grandma Alexander’s recipes. I loved Grandma, but I couldn’t eat her pudding; I wanted to run from the kitchen and hide.

Everyone else finished the meal and I sat alone with my pudding, now cold and soggy. An hour later, Mum snatched my bowl and furiously scraped the contents into the slop dish. Wanting to please her by eating something, I decided on two dry biscuits. I knew exactly how many calories they contained and could eat them without feeling guilty.

Getting the biscuits out of the jar in the pantry cupboard, I nibbled them slowly, trying to make two seem like 12 to show Mum, ‘Look, I am eating, I am eating’. But Mum erupted. ‘Why eat those, and not what I cook?’ she snapped. ‘Isn’t my cooking good enough for you?’

‘Of course it’s good enough, Mum. Everyone loves your cooking,’ I wanted to say. But I didn’t know how many calories were in the rich pudding. My life had become complicated since my periods arrived. I wished they would go away. I was achieving top marks at school, and was helping with jobs on the farm, but was always thinking about food—what I would eat, and how much exercise I would have to do to burn the calories I ate. Mostly such thoughts were a comfort. They helped me feel I could cope, no matter what was going wrong in the family or on the farm.

Occasionally, Mum caught me out: washing my clothes, she would find dried egg yolk, cake crumbs and gravy in the pockets. She would growl but I could not do anything about it. (Neither of us knew that anorexia nervosa was taking over my mind.)

‘I can’t eat,’ I wanted to shout. She made me sit at the dinner table for hours, while she dashed about, doing jobs, but failed to weaken my resolve. She tried to coax, calling me Tim, and tried to threaten, calling me Toby, but the thoughts of my illness were stronger than both of us.

A new challenge arose when Dad announced he would take Joy and me to old-time dancing classes in a Bairnsdale church hall every second Thursday evening. This was in preparation for waltzing and foxtrotting our way into the social life of our local district. Saturday-night dances were held at community halls in our home district of Glenaladale, and nearby Fernbank and Flaggy Creek. I was still wearing bobby socks, but Mum decided the time had come for me to wear a bra. This was wishful thinking on her part because by now I hardly needed one.

She handed the bra to me when I was about to bathe and dress for my first dancing lesson. I shut myself in the bathroom. Probably a hand-me-down from my sister, the white cotton contraption with its multitude of hooks made me cry with frustration as I tried to fasten them. Fearful of being seen, I refused to call for assistance. Finally I solved the problem by doing the hooks up at the front and pulling the bra around my chest until everything was in place. I didn’t want breasts or a bra, but at least the dancing would be good exercise.

After each dance session Dad broke open an 8oz. (220g) block of Cadbury’s plain chocolate to share on the half-hour drive home. At first, having danced for more than an hour, I allowed myself to suck on three small squares, but as the weeks went by, I reduced this to two small squares, then one and then none. I believed that I did not deserve any chocolate. I was happy for Joy, and the neighbours’ children who travelled with us, to eat my share. With each weekly dancing lesson, my clothes hung more loosely.

Home life was changing too. Dad bought a lighting plant. This accumulation of batteries replaced the old diesel motor in the engine room at our dairy, and powered the milking machines. Instead of striking a match to light kerosene-filled Tilley lanterns in the shed in the early morning and at night, Dad now flicked a switch. Linked to our house, electric lights replaced our kerosene lamps, candles and torches. We were becoming modern.

The new power source meant Mum could purchase her first electrical appliances. She especially loved the electric cake mixer, because she could leave it to do the beating while she did other jobs. Dad said the sponge cakes didn’t taste as good as when Mum beat the butter and sugar mixture by hand with a wooden spatula. But there was no going back. Sometimes, while Mum went out to the clothesline or down to the chook yard, I had taken a turn at the hand beating and my arms ached within seconds.

Besides labour-saving devices, Dad bought something for us to relax with: a television set. This box on four legs was given pride of place in a corner of our sitting room. Even with a tall aerial attached to the sitting room chimney, the reception was poor. It bounced off one side of the valley onto the other and we saw two images instead of one. The images were more ghostly grey than black or white, but we could discern a picture. There was no squabbling over what channel to watch because there was only one: the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). We watched television only at night. There was a strict rule about not using electricity until Dad started the afternoon milking about 5pm; this was because switching the power on and off reduced the life of the lighting plant batteries. So each night after tea our family, plus any visitors, proceeded from the kitchen to the sitting room, sat in front of the television set and switched on to the world outside our valley.

At first I was excited, but to watch television I had to sit down. I tried but could not sit still and was pleased when Mum said: ‘You should be outside helping your father. You know how tired he is.’ She was always telling me how tired Dad was. So I pleased her by staying outside, helping Dad, often until after dark. This was preferable to doing sissy indoor jobs, like cleaning the bath with White Lily, polishing the cutlery with Brasso or shining brass doorknobs.

I continued to feed the calves before and after school and the chooks looked forward to their late-afternoon feed of wheat, pellets, and maize. On weekends I helped Dad feed our cows with small, rectangular bales of grass, oats or lucerne; also freshly cut saccaline, which looked like sugar cane, and sometimes silage, a compressed grass that was dark green and smelly but that the cows loved. I sat on top of the loaded trailer and, while Dad drove the tractor around the paddocks on both the flats and the hills, I tossed the fodder to the cows. I always felt happy, working with Dad.

With spring coming, I helped to herd the cows about to calve down from the hills to the lush house paddock, which doubled as a nursery. From there the cows would proceed to the dairy. Separating the newly born calves or poddies from their mothers at about one week, Dad gave them a few lessons at drinking milk from a bucket. I learnt to do this too, putting my fingers in a poddy’s mouth so it would suck, and dipping its nose in the bucket. The paddies soon caught on. I looked after them until they were about three months old and ready to be weaned on to solids like grass and hay. Most of the boy ‘bobby’ calves were sent to the calf sale at one or two weeks of age. The girl calves were lucky—they could look forward to growing into heifers and joining the dairy herd.

Each May and September school holidays, for as long as I could remember, I set traps to catch rabbits, which were a pest. In the past year, Dad had shown me how to set snares on boundary fences for kangaroos and wombats as well.

My latest rabbit catch became a stew. Mum knew I loved the tender, fresh meat, more so because I’d hunted and gathered it myself, but now I refused to eat it.

She was angry. ‘Why won’t you eat, who do you think you are?’ Then, with Dad in the washhouse, scrubbing his hands and combing his wavy hair as he always did before coming to the table, she said, ‘If you don’t eat, I’ll tell your father, and you know he has enough worries already.’

Besides telling me that Dad was tired, Mum was forever providing updates on his worries. We had too much rain, not enough rain; too much wind, not enough wind; butterfat prices were falling, superphosphate prices were rising; in autumn the cows’ milk was drying off too early, in spring the cows were blowing up with milk fever; all year round, machinery was breaking down. I felt the burden of my parents’ worries, but couldn’t eat the rabbit. The guilt caused me to run for miles along the rocky river track, and eat only a dry crust of bread and half a tomato the next day.

At the end of September I began my final term at primary school and was exercising three hours a day. With my thinness more apparent, my mother tried to persuade me to swallow a vitamin mixture. I refused. I hated the smell and feared the calories.

Sometimes she became very upset.

One afternoon after school she insisted I accompany her to visit an old friend, Mrs Banks, a widow, several kilometres around the corner of our valley. Anyone who lived just outside our valley was referred to as being ‘around the corner’. I didn’t want to go, my thoughts were screaming at me not to go, but Mum promised, ‘We’ll take a bunch of flowers and stay only a few minutes’. In the car on our way there, she revealed we were invited for afternoon tea. Dismayed, I said, ‘But I need to be home to do my jobs.’

‘Don’t be impatient, and don’t be rude,’ she warned as she pulled up beside Mrs Banks’ wooden picket fence. Mrs Banks was waiting at her front gate to greet us. The flowers were presented and admired, and we wandered as slow as snails around Mrs Banks’ pretty garden on our way into her cottage. I tried to suppress the urge to run.

Then came the dreaded, ‘Come inside and have a cup of tea.’ In we went, and I sat on a chair beside Mum at the small kitchen table, struggling to keep still while the two women chatted. Wood was fetched, and the fire stoked, to help the kettle boil. It took forever.

I politely declined the offer of a glass of milk or a glass of sugared cordial. Mum glared.

‘I’d like a glass of water, please.’ Things deteriorated fast. Mrs Banks offered a plate of homemade biscuits and cake. I wanted to escape. I could feel my cheeks going beetroot red under my snowy hair as I said, ‘No thank you, Mrs Banks.’

Seething at my poor manners, Mum accepted a biscuit with her cup of tea. The chat continued. ‘Mum’s angry but I can’t stay here,’ I thought. She was about to get angrier because suddenly my hands, on which I’d been sitting, broke loose and I began squirming on my chair, swinging my legs and folding and unfolding my arms. I nudged Mum while Mrs Banks refilled the kettle.

‘I want to go home,’ my eyes begged.

‘Sit still,’ she flashed back. Mrs Banks returned and conversation continued.

Suddenly my anorexic thoughts took over. I stood and blurted, ‘I want to go home to help Dad in the dairy.’

‘Just a few more minutes,’ Mum smiled sweetly. Veiling her annoyance, she said the biscuits were so crisp and crunchy she would eat another one. Pleased with the praise, Mrs Banks offered to write out the recipe. Mum and her neighbours were always swapping recipes.

‘Thank you, Alice, I’m sure Lindsay will like them,’ Mum said.

‘You stay for your recipe and I’ll walk home,’ I chipped in, thinking this was a good time to make a break and the four kilometre walk would compensate for the time I was seated. But Mum stood too, smiled and said to Mrs Banks: ‘I’ll get the recipe another time. We’d better go home now.’

The truth was, Mum couldn’t bear the thought of me walking home along the road. She’d worry a neighbour might drive by and see me not walking, but running. I was an embarrassment.

I raced out of the house to the car. I stood beside the passenger door and hopped from one foot to the other while Mum and Mrs Banks dawdled, with Mum choosing a few plant cuttings to strike for her garden. The farewell at the front gate took an eternity. At last Mum opened the car door and sat behind the wheel of our black FJ Holden.

She was angry. ‘How dare you?’ she raved as she drove us home. ‘You can’t sit still for half an hour. What’s got into you?’

She didn’t know I had anorexia. She didn’t wait for an answer before continuing, ‘You were good. Now you are rude. Everyone will be talking about you and your bad manners. You always want your own way. Why don’t you think of others?’

On and on she went. I said nothing. She would not believe I did not want to be difficult, that my mind was being overtaken by thoughts that were not really me. I wanted to get home and run, run, run to make up for all that horrid sitting down.

One Sunday, a few weeks later, I was invited to play with a school friend, Louise, at one of the grandest farmhouses around the corner. The invitation included Sunday dinner. I didn’t want to go and said I preferred to wander in the bush and look for wombats sunning themselves on their mounds, or watch lyrebirds doing their dance.

‘You have to go.’ Mum was distraught. She didn’t know what was worse: declining the invitation or making me go and risking further embarrassment.

‘You must go,’ she said, exasperated. Joy upset her, and now I was upsetting her, too. It was impolite to turn down invitations.

‘I’ll run away if you don’t go,’ she threatened. Sometimes when my sister was rude, Mum ran out the back gate, slipped through the house paddock’s wire fence and disappeared up the gully. She always returned after a few hours, but I worried and silently resented my sister for being horrid. My sister back-answered, shouted, swore and poked her tongue at Mum. I didn’t understand why, preferring to avoid the house so I didn’t have to listen to the noise. I tried to be good so as not to cause sadness. But now Mum was threatening to run away because I didn’t want to go out for lunch.

Somehow finding the courage to override the urge to stay at home, I said: ‘Yes, I’ll play with Louise and stay for dinner.’

I rode my bike the three kilometres to Louise’s house, the last 400 metres comprising a dirt laneway bordered by a cypress hedge. We had time for a play before lunch so we climbed the hedge, trying to get all the way through, from branch to branch, without putting our feet on the ground. By the time the lunch gong sounded, we looked and smelt like little cypress trees ourselves, with sticky green bits in our hair, inside our blouses and over our woollen jumpers. Exercise was good, but my day was about to deteriorate fast.

The Morrison family, one of the region’s earliest settlers, had a big dairy farm and employed a share-farmer to help milk their cows. Louise and her two older sisters and parents lived in a big cream-brick house surrounded by a rambling cottage garden.

Every child in the district loved going to birthday parties at Louise’s house. We played games like ‘Pin the Tail on the Donkey’ and ‘Drop the Hanky’ before sitting down to a brightly decorated table laden with party food. There would be jelly set in orange quarters, macaroons so light they almost floated away, hundreds and thousands sprinkled on quarters of buttered bread, dainty squares of hedgehog, marshmallow in ice-cream cones and hot sausage rolls. All were homemade.

Until now I’d felt special, being invited to birthday parties and Sunday dinners as well. That was before anorexia developed in my mind. Now, I was filled with dread. Sunday dinner loomed like a heavy black cloud and there was nowhere to take cover.

Louise’s mother was a great cook but to me appeared a stout and scary, no-nonsense woman. Louise had confided several times how she’d had her mouth washed out with something that tasted horrible for telling fibs. Now I sat at the kitchen table with the family, a plate loaded with slices of roast beef, baked potatoes and pumpkin and boiled peas, drenched with rich gravy, before me. I felt I was before the firing line.

Fearful as I was of Mrs Morrison, I could eat only the peas; terrified, I ate them slowly, one at a time, trying to avoid the gravy. There was no opportunity to shift food into my pocket. So I shifted it around on my plate, and pretended to eat, but I was fooling nobody. Looking downward, sensing everyone was staring at me, my face turned bright red. I wanted to disappear under the table.

‘This is the worst meal in my life,’ I thought. ‘Everyone has finished eating and is waiting for me.’ At last Louise’s mother removed my plate. ‘What a wasteful child,’ I knew she was thinking.

Without a word, she served dessert. Big bowls of jelly, custard and preserved peaches, topped with a blob of thick cream fresh from the dairy, were passed around the table. Normally I would love this but now studied my bowl with a sinking heart. The jelly and custard had been sweetened. The peaches were submerged in syrup. Louise’s dad and her big sister cleaned their bowls and left the table. Her mother was clearing the table and washing the dishes.

I sat, too scared to move, apart from my swinging legs, out of sight under the tablecloth. Louise sat loyally beside me. At last we were shooed outside. Relieved, I didn’t want to stay a moment longer and said I had to pedal home.

‘Got to help Dad with the cows and calves,’ I said.

I feared that Louise’s mother would telephone Mum and tattle. Sure enough, as soon as I entered our back door Mum lectured me on my pig-headedness and poor manners. ‘Blow Louise’s mother,’ I thought. She had phoned to ask if I was sick, but I’m sure both mothers considered my behaviour just plain rude. I couldn’t wait to get outside to start my jobs and to be alone with the bossy thoughts in my head. Mum did not make me go for meals at anyone’s house again.

There was one social event I could not avoid. One evening during the week before Christmas, everyone in the Glenaladale, Woodglen and Iguana Creek district gathered for our primary school’s annual concert in the ‘Glen’ Hall. Gum tips, colourful paper streamers and bunches of balloons camouflaged the unlined timber walls. The Christmas tree was a big cypress branch, standing in a 44-gallon drum covered in red and green crepe paper. Our mothers helped us to decorate the foliage with balloons and paper chains, angels and Chinese lanterns that we had made with small squares of coloured paper at school. Set in the corner beside our little performance area, the tree evoked much excitement as the mothers’ club members placed gifts around its base. ‘Which one is mine?’ the children looked at each other and giggled. Anticipation mounted as we presented our carols, skits and nativity play. Our parents laughed and clapped.

Normally I would be as excited as everyone else, but tonight I stood in the back row, trying to hide in the shadows of the tree. The concert over, a bell clanged and the children clambered to sit on the front wooden bench, as big, jolly Santa entered the hall door, waving his bell and singing ‘Ho, ho, ho’. He called to us, one by one, asked us what we wanted for Christmas and gave us our gift from the tree. Over the years I had asked for a pony, a gun, and a cowgirl suit. I didn’t know what to ask for this year and didn’t care. I could not laugh or smile. Santa gave me a pen, commemorating completion of Grade Six, and I hurried back to my seat.

I wanted to go home. I felt removed from my friends and sensed their parents were looking at me.

My chest was flat and my periods were sporadic; my mind was full of thoughts of food and exercise. Anorexia had dominated my final year of primary school.

Christmas Day was not happy for my family that year. My city cousins, who gave me an excuse to sleep on the verandah, didn’t visit because they had moved from Melbourne to Portland, on the western side of Victoria,

too far to travel to our farm.

So there was just Mum and Dad, Joy, me, Grandpa and a few old family friends for Christmas dinner. For a gift, my parents gave me a beautiful, solid timber, locally made desk. Complete with pencil tray and drawers, it was an encouraging acknowledgement of my budding writing passion. I’d won my first essay competition at the age of nine; I wrote about rice and the prize was a fountain pen. More recently I had been writing adventure stories, sometimes reading them at school, and some were published in the Australian Children’s Newspaper.

For Christmas dinner I tried to impress Mum by eating a boiled chicken leg, my first meat in months, and a big serve of boiled cabbage. Lately I’d been eating a tomato for dinner so this was a feast. By now Mum had accepted that putting food on my plate was a waste if I said I would not eat it. There was no point giving me roast beef, lamb or pork, roast potato, pumpkin, and thick, brown gravy, or any of the plum pudding, served with warm custard sauce and cream. Mum did not need to hide any threepences or sixpences in a pudding serve for me that year.

She was pleased I ate the chicken but afterwards I ran up the hill behind our house, to work that chicken leg off while bringing the cows home to be milked. We were in a drought, and the cows had to walk a long way from the dairy to feed on pasture between milkings. Now that I was on holiday, I happily herded the cows to the far paddock in the morning, and collected them in the afternoon. I also set more rabbit traps.

Nature had a strange effect in a drought. Rabbits were plentiful and I caught some without disguising the traps with the usual square piece of newspaper under a layer of soft, powdered dirt, at the entrance to their burrows. Grey, white, ginger and black—I’d not seen such colourful little bunnies before. They were emaciated like me. I could not eat because my anorexia was dominating my mind. The bunnies could not eat because there was no food. I put them out of their misery, breaking their necks, not bothering to take them home to skin.

Two days after Christmas Day, Mum baked a big sponge cake, filled the halves with whipped cream, iced the top in pink and decorated it with sprinkles for my 12th birthday. A year ago I was full of fun and vigour. Now, almost a skeleton, I tried to appear excited when unwrapping my parents’ gift to find my first wristwatch, but could not eat one crumb of the beautiful birthday cake.