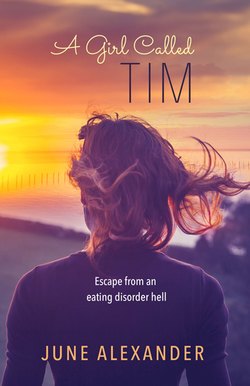

Читать книгу A Girl Called Tim - June Alexander - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1. SCHOOL DOCTOR VISIT

ОглавлениеI loved sleeping in my camp bed on the wooden verandah. Except for the bloody flies. As soon as the summer sun peeped over the hill and into our river valley, the dopey things woke up and started buzzing around my head.

This particular January morning I tried to swat one that landed on my face. The sudden movement caused my narrow bed to wobble on its shaky legs, their rusty hinges creaking loudly. Oh well, the flies were a sign it was time to get up anyway. I had big plans for the day.

School holidays were always fun on our family dairy farm, and the 1962 summer holidays held much promise. My days were full of helping my dad milk the cows, feeding the calves, shifting spray irrigation pipes, playing cricket with my cousins and swimming in the river. At 11 years old, I was a tomboy through and through, and proud of it.

As I stirred in my bed, so did Topsy, my tortoiseshell cat. She burrowed under the covers and kept my feet warm during the chill of the night, but now she knew it was time to rise. I lay still for a moment and listened, beyond the buzz of the flies and Topsy’s purr, to the gentle rumbling of rapids as the clear waters of the Mitchell River trundled over a stretch of rocks, 500 metres down the hill from our farmhouse. The roosters were crowing, Rip the dog was barking, the cows were mooing and the milking machine engine was putt-putting away.

Our farm was nestled at the head of the fertile Lindenow Valley, through which the river wended towards Bass Strait via Bairnsdale and the Gippsland Lakes, about 30 kilometres away.

People entering the valley floor along Findlay-Alexander Road would round a corner and see our Federation-style house a mile straight ahead, its red roof peeping over the hedge of mauve-flowering bougainvillea like a welcoming beacon. Smoke rising from a tall red-brick chimney was a sure sign someone was at home. The narrow gravel lane petered out to a dirt track at our farm’s big entrance gate, and hardly a day went by without someone calling in for a cuppa. A smaller, period-style garden gate led from the house paddock into the house yard where, sheltered by the bougainvillea, a large and colourful cottage garden prospered.

A circular concrete footpath arched uphill through the garden to a grand, leadlight front door on the left. Only strangers knocked on that door—usually peddlers, evangelists or people who had lost their way. Everybody else followed the path to the right, leading to the back door. In constant need of new fly-wire, this door opened into a small porch where we hung our coats and hats. The washhouse was to the right, the kitchen was directly ahead and the passage was to the left. The passage, about as long and wide as a cricket pitch, led straight to the front door. Along the passage, doors on the right opened to the pantry, the bedroom I shared with my sister, Joy, who would soon be 14, and the sitting room; doors on the left opened to the bathroom, my parents’ bedroom and the top room, or guests’ bedroom.

The front door opened onto the L-shaped wooden verandah. From there, views extended over flowerbeds, lawns dotted with cypresses shaped like giant high tin loaves and a garden border of sprawling, mauve-coloured bougainvilleas, to the lush valley beyond. The verandah was the adults’ favourite place to sit and chat—especially in the morning sunshine, and again in the afternoon and evening, when the hot sun had sunk behind the house. They sat on a wooden bench and also on my camp bed—no wonder it was creaking! The verandah was also perfect to spot people ‘coming up the road’.

One of the first things we explained to newcomers was that the toilet—its white weatherboards and pitched, red corrugated iron roof matching our house—was out the back gate in the house paddock. When nobody was around you could leave the toilet door open and gaze over the gully and hills. The view was enough to help the most constipated person relax. Besides the outhouse, the six-acre house paddock was home to the hen house, wood heap, orchard, car shed, tractor shed and stable.

My paternal grandfather, Duncan Alexander, built the house shortly after purchasing what was then a 52.6 hectare property in the early 1900s. A small, spritely man who played golf in his younger days and had a lifetime passion for fishing Gippsland rivers, Duncan grew up in the tiny township of Walpa, near Lindenow, about 13 kilometres from the farm. Walpa had developed during the late 1800s and early 1900s when land was opened up to pastoralists and selectors.

Duncan married Alvina Whitbourne, an accomplished horsewoman who was raised on a property beside the Mitchell River at Wuk Wuk, a settlement between our farm and Lindenow. Alvina was a descendant of the pioneering Scott family who had travelled with a horse and dray across the Great Dividing Range from the Monaro High Plains in New South Wales to settle at Delvine Park, near Bairnsdale, in 1845.

My paternal grandparents had two children—Carlie, born in 1920, and my father, Lindsay, born two years later. Carlie married young and moved to Melbourne while Lindsay insisted on leaving school at 14 to be a farmer. In 1947 he married my mother, Anne Sands, one of eight children born to Neville and Elizabeth Sands. Elizabeth was the daughter of a miner and Neville was a miner too. Early in their marriage, Neville worked in the black coal mine at Wonthaggi, in South Gippsland. Suffering health problems, including the loss of a lung, he and his young family moved east to Bairnsdale, where he worked in orchards before settling a little further east, at Buchan South. My mother was born there, at home, in 1925. My grandfather Neville worked in a nearby quarry, extracting black marble. Some of this marble was used to create 16 Ionic columns for Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembrance, which opened in 1934, and some was shipped to London for inclusion in Australia House.

Around 1940, the Sands family moved 100 kilometres southwest to Woodglen in the Lindenow Valley to work on a dairy farm. My mother, 15 by this time, and her sisters, Margaret and Gladys, worked with their father in the milking shed. My mother couldn’t remember a defining moment when she met my father, but as they lived only four kilometres apart, they possibly met at a dance in the nearby Glenaladale Hall, at a local cricket match or tennis tournament. They wed a few weeks after my mother’s 21st birthday and lived in the same house as my grandparents. My sister, Joy, was born in 1948 and I followed on December 27, 1950.

When I was five years old, my grandparents moved into a house in East Bairnsdale, 28 kilometres away. Joy and I sometimes stayed with them. This experience of ‘town life’ included a playground and milk bar in the same street, friendships with children across the road, and an occasional outing to the picture theatre. Mostly I was desperately shy and sought shelter behind my sister.

Grandpa Sands was the first of my grandparents to die, when I was seven. In my favourite memory, he sits on a small wooden bench on the verandah of his rented fibro-cement farmhouse at Woodglen, playing his button accordion. Grandma Alexander died when I was 10. I was not taken to either funeral. I missed my grandmother especially. She had patiently taught me, a left-hander, how to knit and crochet. I talked to her in my prayers every night. When she and Grandpa Alexander lived on the farm, I occasionally awoke in their bed, always feeling safe and snug with a grandparent either side of me. My parents placed me there when my bed was needed for visitors. Grandma would scratch my back, let me help undo and do-up her tight-fitting corsets, and brush her beautiful, long, silvery-white hair that she pinned into a neat bun during the day.

When Grandma died, she left a small Vegemite jar with a hand-written piece of paper taped on top, stating: ‘ This is June’s’. The jar contained pennies, halfpennies, threepences and sixpences. I treasured that little jar, more for its message than its contents. In years to come, those three words, penned in my grandmother’s hand, would give me strength.

After my grandparents moved to Bairnsdale, their bedroom became known as the ‘top bedroom’ for guests. From the age of five to 10, when my bed was required for visitor over-flow, I slept on an inflatable rubber mattress on the floor of my parents’ bedroom. By summer 1962, I was sleeping on the camp bed on the verandah. Visitors at this time of the year were mostly city cousins, and their parents, my Aunty Carlie and Uncle Roy.

My cousins were allowed to sleep in, but I knew that when my mother came briskly out the back door, like now, I had two minutes in which to get up. That’s how long she took to go out the back gate to the toilet to empty her chamber pot, rinse it under the garden tap and return it inside to its seclusion under her bed. I needed to jump out of bed before she came out the back door again, this time to briskly sweep the concreted garden path. Otherwise, she would wave the broom to remind me that Dad was expecting his tea and toast. Besides, if I didn’t get up right then, the flies would drive me crazy.

I threw off the thin grey woollen blankets and swung out of bed, pulled on my shorts, T-shirt and gumboots, headed for the back door and yelled: ‘Mum, I’m ready to go to the dairy—is Dad’s tea and toast ready?’

She loaded me up with a chipped enamel plate carrying several thick slices of high tin bread. The bread had been toasted on a homemade wire fork over embers in the firebox of our small, shiny, black wood stove, and soaked with butter. An old saucepan lid was placed on top to keep the flies off. With this in one hand, I took the handle of the shining clean billy, half-filled with well-sugared black tea, in the other, and plodded in my boots down the garden path, out the front gate and down the gravelled track to the unpainted weatherboard dairy as fast as I could without slopping the tea or dropping the toast.

While I walked, I thought about what the day would bring. My cousins and I had made plans the previous night for a maize cob fight in the stable after breakfast, followed by a swim in the river before lunch. My favourite ‘swimmy hole’ was by the willows and windmill downstream from the rapids. There, depending on water flow, the river was about 50 metres wide and was bordered with a small sandy beach on the far side.

I took over milking our cows while Dad stood in the dairy’s wash-up room and ate his toast, washing it down with a pannikin of tea poured from the billy. Our dairy herd of about 45 cows was milked four at a time with machines powered by a diesel motor. By the age of 11 I knew pretty much how everything worked, as I’d been going to the dairy since I could walk. At first, my parents sold cream in cans that were collected by a lorry and taken to a butter factory in Bairnsdale. The leftover milk was fed to our pigs. Then we progressed to selling water-cooled milk. The milk, always deliciously warm, frothy and sweet, fresh off the cows, was cooled as it ran over small stainless steel bars filled with water from an underground tank. After cooling it was stored in a big stainless steel vat until the milk tanker came, once or twice daily, to collect it.

I managed to milk a few cows before Dad returned to the yard and then I fed the calves. First I went to the wash-up room, which was more modern than our house because a briquette hot water service provided running hot water. I used a well-worn broken axe handle to mix powdered milk with water in two big stainless steel buckets. To prevent lumps forming and floating on top, I mixed the milk with first cold and then hot water. For extra nourishment I added fresh milk from the big vat, and heaved the buckets, swinging one and then the other, trying not to let milk slosh into my gumboots, to the wooden calf pens behind the dairy.

I poured the milk into tins, made by Dad from five-gallon (19 litre) oil drums, and fed the calves, which were bellowing for their tucker. Knowing the greedier calves would drink fast and headbutt for more, I held onto the tins’ wire handles and used a stick to ensure the little ones got their share. Minutes later, tummies full and tails swinging, the calves pranced and kicked up their hooves as I shooed them out of their pen into the calf paddock. Checking that their trough, which had been carved from a log, was filled with fresh water, I returned to the wash-up room to scrub the buckets. I washed Dad’s tea billy too, and filled it with fresh milk to carry up the hill for Mum to serve at breakfast.

My lazy cousins were still in bed. Wondering where Mum was, I heard her call from up the hallway. I found her in her bedroom. Bother! What did she want?

Mum closed her door. This seemed serious.

‘Tim, I have something to tell you.’

What had I done?

‘Did you notice anything when you got up this morning?’

Notice anything? What?

I hadn’t made my bed but Mum usually made that for me while I was out helping Dad with the farm jobs.

‘No,’ I said.

‘Did you notice your pyjamas, or look at your sheets?’ she asked.

What had I done? Had my cat made a mess? Couldn’t have been me.

‘No,’ I said.

‘I found some blood,’ Mum said.

‘Blood? What blood?’

Then Mum was talking. I could hear her but absorbed only snatches of what she said.

After talking about ‘periods’ and ‘bleeding every month’, she withdrew a small book from her dressing table drawer and told me to read it. The book’s title was something like Mothers and Daughters. I thought I’d read every book in the house long ago, but I hadn’t seen this one before.

Then Mum pulled something from another of her dressing-table drawers. It was a thin, circular, elasticised belt with two dangly bits. From a bag in the depths of her wardrobe she pulled a white flannelette nappy. I watched, numbed and horrified.

Spreading the nappy on the blue eiderdown of her freshly made bed, she folded it several times into a thick, narrow shape. Next, using two large safety pins from a little box on her dressing table, she attached the ends of the nappy to the two dangly bits. Mum held her work of art out towards me and said, ‘Wear this pad.’

I took it, speechless. My mother walked from the room, closing the door behind her. But not before pausing to add: ‘And no swimming today or tomorrow; not until you finish bleeding.’

I didn’t want to hear any more. I felt disgusted. Me, wear a nappy, a baby’s thing?

Left alone, I slowly lowered my shorts and my pants. There was a little red patch. I took my pants off and pulled the bulky pad on.

I felt a great need to escape that bedroom, and the house. I shoved the book under my camp bed pillow on the verandah, pulled on my gumboots and headed back to the dairy to help Dad wash the yards and clean up after the milking. As I walked down the track, kicking pebbles with my boots, I stopped. My mother’s words hit hard, like a lightning strike. My world had changed forever. For a week every month I would have that bleeding—because I was a girl. I didn’t want to be a girl; I liked being Tim. This was what Mum called me when she was happy with me. When she was annoyed, she called me Toby.

I’d wanted to be a boy for as long as I could remember. My boy cousins had shown me their ‘willies’ and I wanted one, too. My ‘fanny’ was a huge disappointment. At the age of six or seven I had lined up beside several boy cousins in the grassy calf paddock. Together we had lowered our shorts and faced the timber wall of an old storage shed. We’d stood two metres out from the shed and our goal was to see who could ‘pee the highest’ up the wall. ‘Ready, set, go!’

The boys’ wee reached almost as high as the shed roof. I leaned back and pushed as hard as I could but mine didn’t go beyond the toe of my gumboots. Most of the warm yellow liquid fell directly south into my boots, soaking my socks and making my feet squelch and smell. Not having a willie was frustrating, but to learn that my fanny would bleed once a month was devastating.

I shook myself and trudged on to the dairy. I was sure I was as handy as a boy in all other ways. I preferred farm work to house jobs. Besides feeding the calves twice a day and helping with the cows, I set rabbit traps, drove the tractor and helped to shift the irrigation pipes.

Would Dad notice I was different? He said nothing as I entered the dairy to sweep and hose the yards and help put water through the pipes to clean the machines now the last cow had been milked. But that stupid nappy was chaffing my inner legs. I hoped it wasn’t bulging through my shorts. By now it was nine o’clock. I walked back up the hill for breakfast.

My sleepy cousins were starting to appear.

They said nothing. Just as well they didn’t know about this sudden complication in my life. They would laugh if they knew I was wearing a nappy. After breakfast, in the stable downhill from the house, we drew an imaginary battle line and prepared for the maize cob fight. We gathered old, shelled cobs off the dusty dirt floor for ammunition, hid among the bales of hay, old machinery and hessian bags brimming with full cobs, and the war started. Mum growled if we threw full cobs, as they were food for the chooks, but in the heat of battle we threw them anyway. That day we decided the Allies were invading Germany. The cobs, especially if unshelled, hurt if they struck bare skin, and that was our aim. We had to draw blood on the enemy, usually on their face or arms, to claim a victory.

Waging war helped me to momentarily forget my other bloody problem, but I had to mumble, ‘Mum wants me to do a job in the house’ when my cousins asked why I wasn’t going for a swim.

‘Chicken,’ they said.

The next few days seemed like years, but then I was free to go swimming again, between helping Dad with the cows and shifting the irrigation pipes on our 24 hectares of river flats.

My happiness was short-lived. In the first week of February, I pedalled my bike out of the valley to attend the local state school, Woodglen Primary, Number 3352, five kilometres away. Surrounded by farmland and flanked on three sides by tall pine trees, the school comprised one classroom, a porch where we hung our bags and where the little children listened to ‘Kindergarten of the Air’, and a tiny storeroom for our sport equipment. I was in Grade Six, my final year of primary school, and my cousin Daryl was the teacher. Daryl, who had been my teacher since Grade Four, had grown up in Melbourne but I knew him well as, along with many other cousins and family friends, he often stayed at my parents’ house.

There were five girls and three boys in Grade Six. Our grade was the biggest in the school, which had a total enrolment of 24 children. Most of our parents were dairy farmers. Some, like my parents, owned their property; others, including a recently arrived Dutch family with 13 children, share-farmed on a larger property.

I enjoyed learning, but something about Daryl made me uneasy.

Every morning we stood beside our wooden desks and he said: ‘Good morning, boys and girls’ and we’d chorus: ‘Good morning, Mr Orgill’ before sitting down to work. Except I refused to say ‘Mr Orgill’. He was my cousin, after all, and only 12 years older; he wouldn’t let me call him ‘Daryl’ at school, so I called him nothing. This meant I rarely put my hand up to volunteer a ‘morning talk’, even if I had some world-breaking news, because we had to open our show-and-tell with ‘Good morning, Mr Orgill, girls and boys.’

But one day he announced that everybody in the school had to take a turn at presenting a morning talk. I don’t remember what I spoke about, but I do remember weeks of anxiety, worrying about how I was going to get the courage to say ‘Mr Orgill’.

My mother and sister, Joy, called me ‘stubborn’ and ‘pig-headed’. I couldn’t help it. Something about Daryl had me on edge.

Every Monday morning we lined up by the weatherboard shelter shed for a flag-raising ceremony and sang God Save the Queen. Standing at attention with my hand over my heart one morning several weeks into Term One, I glanced along the line and my heart went thump as I realised I was the only girl with breasts.

When I ran, my breasts bounced up and down and hurt. If I held them they didn’t hurt, but I couldn’t do that when playing with the boys or within sight of Daryl.

In March, ‘Mr Orgill’ announced that the school doctor, who visited our school every three or four years, would come in June. He gave us forms for our parents to fill in and sign.

I gave my form to Mum, saying I didn’t want to see the doctor, but she said: ‘Don’t be silly, you have nothing to worry about, Tim. It will be over in a flash, you’ll see’.

Her words provided no comfort. I would have to undress to my panties and singlet. Maybe I would have to take off my singlet as well. I’d be in the classroom, which had large multi-paned windows on two sides, and no curtains. For a reason I could not explain, I was extremely fearful of Daryl seeing me undressed.

My sister, Joy, brushed my concerns aside. Daryl hadn’t been her teacher, since she’d started high school at Bairnsdale the year he came to Woodglen, three years ago now. Joy and I shared the same bedroom and Daryl gave her the creeps too, but when I said I didn’t want to see the doctor, she said: ‘All the other girls will be undressing; you won’t be the only one.’

But I would be the only one with sissy breasts. This was definitely something I couldn’t talk to Dad about. I had nobody else to turn to.

The doctor’s visit was only three months away and my breasts were growing bigger. Soon I would need to wear a bra. This was a big worry.

Sitting on the grassy school ground in the shade of the pine trees during playtime one Friday afternoon, there seemed no way to avoid the doctor’s visit. Suddenly, however, I knew what to do.

It was as though my brain was zapped from outer space. Ping!

Anorexia nervosa was developing and starting to manipulate my mind. Oblivious of this, I only knew I felt less anxious.

Classmates were calling me to come and play; they could not see my special new ‘thought-friend’.

That afternoon, when classes resumed, a health lesson serendipitously provided encouragement. With other pupils I sat cross-legged on a carpet square with my health booklet to listen to the voice booming from our big wireless. It described a new word: c-a-l-o-r-i-e. A day earlier the word would have held no interest but now my mind clung to it like a magnet.

The lesson was about food values and burning energy. My booklet listed the calorie content of several foods and the number of calories absorbed in 30 minutes of walking, swimming, running and bike riding.

My mind recorded the entire lesson word for word and I immediately began to eat less and exercise more.

When tempted to eat, I pushed my hunger pangs aside. The more hungry I was, the better I felt. If I was feeling weak, I brushed my teeth, which helped me think I had eaten a meal, though I’d eaten nothing.

I had no idea of my weight. The only scales I had seen were those belonging to the school doctor, or those with a penny slot outside chemist shops in Bairnsdale’s Main Street. I went to town three or four times a year and was too shy to weigh myself in view of passers-by. All I knew was that I wanted to lose my breasts before the school doctor’s visit.

Until now, I had been pleased when my clothes became tight, because this showed I was growing, and I wanted to be tall and strong, like Dad. But now I didn’t want to grow. I could not be like my dad, and didn’t want to be a girl, either.

I continued to feed the calves before riding my bike to school, but did my jobs faster so I could work out on the playground equipment before lessons started.

I swung across the monkey bar and, like a monkey after a coconut, shinned up the pole; I reached for the clouds on the swing, did chin-ups, climbed the ladder, zipped down the slide, and turned myself inside out on the jungle gym. I worked out again at playtime and lunchtime, counting and always increasing the number of turns on each piece of equipment. My friends could not keep up with me.

At home I chopped more wood, looked after the chooks and fetched the cows for milking, running from job to job.

Mum and Dad thought I was wonderful. Mum was calling me ‘Tim’ all the time, I was so helpful, and I almost burst with pride when Dad told an uncle that I was a left-hander at writing but was his ‘right-hand man on the land’.

Exercise was easy but eating less was more complicated as Mum was in charge of the kitchen.

Breakfast was straightforward. Mum was usually helping Dad in the dairy when I was in the house changing out of my cow yard gear into my school clothes. She would leave the table set with Weet-Bix on a plate or porridge keeping warm in the saucepan on the side of the stove, thick slices of bread on a plate to toast and tea in the pot. Joy left an hour earlier to catch the bus to high school and any visitors would still be in bed.

The cats loved the porridge and Weet-Bix. Besides Topsy, we had about 12 cats. Some were part feral, having been dumped by uncaring owners in the bush land adjacent to our property. Timid, they lived in the stable and haystack where they caught mice; some bravely hung around the back door of the house in the mornings and evenings, hoping for a dish of stale milk, or scraps from the kitchen.

They purred as I fed them my cereal, urging them to eat it all before Mum returned from the dairy. Next I took a thick slice of high tin loaf outside, through the back gate, throwing chunks to the chooks, who snapped the bread up in their beaks and dashed about, clucking madly and throwing their heads back as they gulped their treat down. Then I ran back inside, cut a paper-thin slice of bread to toast on the open fire, spread some Vegemite and washed it down with a cup of black, sugarless tea. From the age of five I’d been drinking tea from a favourite cup that Mum half-filled with milk, and sweetened with several teaspoons of white sugar. Not any more. Every day I found new ways to reduce my calorie intake.

Lunch on school days was easy, too. Mum cut two big rounds of sandwiches, wrapping them in waxed paper and placing them in my blue lunch tin, the lid kept on with an old Fowlers Vacola preserving jar ring. I asked for only one round but she wouldn’t listen and when I came home from school with one sandwich untouched, she was upset.

‘You need two rounds; you’re a growing girl. And besides, this is wasteful,’ Mum scolded.

I thought of another solution. The next day I took an empty tin home.

‘That’s better,’ Mum said.

Some children at school came from poor families who sometimes had no bread for making lunches, so I offered my sandwiches to these children. I gave them the cheese, jam, meat and peanut butter sandwiches, keeping a Vegemite, fish paste or tomato one for myself. My classmates also enjoyed my play snacks of lamingtons, jam drops, Madeira cake, chocolate slice and Anzac biscuits. I smiled as they ate while I went hungry; I enjoyed watching them eat.

The evening meal was the one daily meal shared by my family. Mum served the food on our plates and set them on the oval-shaped, oak dining table that stood in the middle of our kitchen. I dreaded casseroles, stews and gravy. Desserts were particularly messy.

I became resourceful and devious. By sitting down first, when Mum’s back was turned at the sink and others were combing their hair before coming to the table, I had time to move food from my plate to the next plate, which belonged to whoever was visiting. This was a relief. If Mum left the kitchen for a moment, I risked reaching across the table and placing my meat on Dad’s plate. Sometimes I gave his plate a roast potato as well. These were his favourite foods and together with Grandma, Dad was my favourite person in all the world.

When everyone was seated and busy eating or talking, I grabbed fistfuls of food left on my plate, whipped it under the tablecloth and slid it in my pockets. This was why I didn’t like sloppy foods, like mashed potato and meat covered in gravy. I ate a small amount of cabbage or carrot, and pretended it was a lot, chewing it over and over, finishing my meal at about the same time as everyone else. Or I pretended to chew and swallow nothing.

Main courses were a trial but desserts were worse. They were sticky or soft and hopeless for slipping in pockets.

Mum made chocolate sauce puddings, apple crumbles, apple puddings, golden syrup dumplings, jam tarts, sago puddings and custards, usually served with stewed or preserved fruit. Made with full-cream milk and butter, the desserts also contained sugar, available by the cupful from a big hessian bag in our pantry.

My heart sank when Mum insisted on pouring custard sauce or cream over the top of a steamed pudding. About the only dessert I could slip safely in my pocket was cinnamon apple cake, and even that was messy.

I tried to tell Mum, ‘I’m full. I don’t want dessert, thank you,’ but she would reply, ‘What’s wrong with you? I thought you wanted to be tall and strong like your Dad.’

Nothing but a cleaned-up plate satisfied my mother. She would remind me how as a child she ate ‘bread and dripping through the week and bread and jam on Sunday,’ and for good measure would add: ‘Think about those poor starving children in India, be grateful and eat up.’

I couldn’t see how the eating of my dessert would ease the plight of children in India. I wanted to lose my breasts. I couldn’t tell Mum that, so I waited for everyone to leave the table and for her to leave the kitchen, even for a moment. Then I’d jump up and toss the food off my plate into the scrap bowl and run it outside in the dark to Rip the dog, whose turn it was for a meal at the end of the day. Rip developed a real sweet tooth.

Summer passed into autumn, and autumn was nearing winter. My periods were on time every month. At school, I remained the only girl with breasts but they were shrinking and I hid them by wearing more clothing as the weather turned cooler.

However, Mum was starting to question my behaviour. I was quieter and on weekends, I liked to disappear into the bushland adjacent to our property, my thoughts as my companion. My mother and sister called me ‘stuck up’ and ‘rude’ when I didn’t want to join them in visiting our neighbours, who put the kettle on for a cuppa, whatever the time of day, and served sugar-laden cakes and biscuits.

I had friends on neighbouring farms but preferred to be alone or doing outdoor jobs. Luckily Mum liked me to help Dad and I was with him every possible moment. She worked hard, helping on the farm when I was at school, and she kept our house spotless and our large cottage garden beautiful.

Some local families had electric power, but it hadn’t entered our valley yet, so Mum did her housework manually: polishing the linoleum floors on her hands and knees, beating her cake mixtures with a wooden spatula, and washing our clothes in a wood-fired copper. She prodded the clothes with a broken axe handle before heaving them into a concrete trough to rinse in cold water, and wrung them by hand before pegging them on the outside line. The steel-bladed Southern Cross windmill by the river provided our water supply, pumping water to a tank 100 metres uphill from the house to gain sufficient pressure. Careful usage was essential because otherwise, when the wind didn’t blow, the tank ran dry.

One night, lost in thought over how to avoid the shepherd’s pie that Mum was baking for tea, I forgot to turn off the tap into the calves’ trough. Next morning, Dad gently asked, ‘Did you forget to do something last night?’ The tank had run dry. I blushed and hung my head. I would not forget again.

The following week the doctor came to school. My chest was almost flat. As far as I could tell, Daryl stayed out of sight. Nobody laughed as I lined up with the other girls in panties and singlets. The doctor chatted, probed and listened to each of us in turn before passing us on to the nurse who weighed us. At 6st 12lbs (43.5 kilograms), neither the doctor nor nurse noted my weight loss because they hadn’t seen me for four years.

My report was good on every count. While dressing I looked sideways and was pleased to notice other Grade Six girls were growing breasts too.

I had worked hard for three months, preparing for the doctor’s visit. Now it was over. That afternoon, pushing my bike through the school gate to pedal home, I felt relieved I would not have to risk making Mum cross at mealtimes any more.