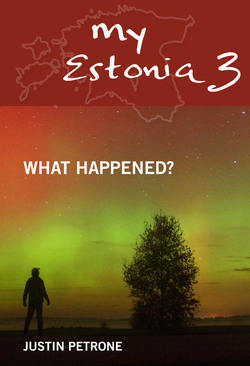

Читать книгу My Estonia 3. What Happened? - Justin Petrone - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THAT HOLE

ОглавлениеIt was easy to get distracted in the toilet of Cafe Fellin because of the words on the inside of the door.

The words told about the origins of the name Viljandi, the picturesque and peculiar small town in Estonia where we lived. They were written by a local historian and typed below an old photograph of the lake front and its many villas. It was framed and covered in glass. In the cafe with its white wooden furniture and pleasant spirals of floral-printed wallpaper, you could hear the people bustling and glasses clinking, the fidgeting of a jazz guitarist, and maybe somebody waiting on the other side of that toilet door, turning the knob to remind one of the urgency of the situation. But that was too bad. I was still reading.

The Vi was an older form of vee, water in Estonian, the historian had written. The Ljandi brought to mind the ancient name of Tallinn, Lindanisse, which meant a town or stronghold. And so, there it was: Viljandi, the town on the water. It was still true in part. In old illustrations and wood carvings, you could see that the lake beside this town was higher, and the rivers were higher, too. I had heard that one could sail to Viljandi with the right kind of boat, navigating down long-lost waterways. Back then, Viljandi was a Hanseatic merchant town, connected to the outside world by its waters.

Nowadays, it felt more like a backwater. To get anywhere from Viljandi, you needed to drive. A trip to the capital, Tallinn, and back could take five hours out of your day. The second biggest city, Tartu, with our publishing house, was an hour to the east. The beach and spa resort Pärnu was an hour to the west. And I didn’t even bother taking note of how long it took to get to our farm house in Setomaa on the Russian border. On those long days, I just drove and drove.

Some people didn’t think Viljandi was a backwater though. For these self-electing few, Viljandi was a bohemian jewel sparkling with artists and activists and eccentrics, hidden away from the crass commercialism that had afflicted the rest of the country, a respite for those who preferred to see their children fingering zithers and playing among castle ruins rather than sitting behind a computer.

There were also those who condemned the so-called “city” of Viljandi as a depopulated outpost of alcoholics and pensioners. A friend, who had left Viljandi, referred to his hometown as “That Hole.”

“How can you stand living in that hole?” this Estonian friend would ask me. He had left “That Hole” when he was eighteen and never looked back. Now I wasn’t even sure what to call him. His mother had named him Priit, but after he moved to Hollywood and started a career in music and film, he started calling himself “Brad.” Brad Jurjens, you know, like Brad Pitt. Each year, he returned to visit his mother in “That Hole” for a few weeks, then he was gone again, back to the City of Angels. When he did come to visit he would invite me out to a pub, where he would guzzle beers, check out girls from behind his shades, and ask me awkward questions.

“You’ve got to explain it to me. How can an American guy like you stand to live in a hole like this?”

“You really think your hometown is a hole?”

“Of course it is! Why do you think I left?”

The same question was more or less posed to me by my new acquaintance Diego when he stopped by during the Viljandi Folk Music Festival, and asked in a low and weary voice, “How can a guy from New York like you stand to live here?”

“You mean in this hole?”

“Si.”

Diego didn’t ask me this question in front of our Estonian wives. No, he decided to wait until we were out in the street to spring it on me. It still wasn’t much of a street. Sepa, or Smith Street, was more of a dirt path when our family moved in. There were some remnants of cobblestones, but most had been dug up and sold by some entrepreneurial Viljandier in the past, and what was left was so mottled that I had even come to fear it, mostly in autumn and spring when the rains came or when the snows melted, because deep puddles would hide amongst the muck and your car would hit them hard and get stuck. Whenever it did, I would think of my Estonian friend in Hollywood and chuckle about “That Hole.”

The street that day though was still under construction, full of mud and sand and new pipes sticking out at strange angles.

There was also hope. For a long time, I had feared that nothing in Viljandi would change. And yet it had changed in my few years spent there, mostly for the better. It just took longer for the change to arrive to Viljandi than it did in the bigger Estonian towns. I was sure that Sepa Street would once again be proud. Perhaps most of the city would follow. A fully functional cinema would open one day, maybe even a spa.

But that would take more time. On that day there were still rotting planks over the stagnant puddles. The faint musk of dog feces snaked through the air and into the nostrils, and since you could never seem to see the source of the stink, you just had to wonder if it was new excrement or perhaps older, medieval, archaeological scat, that had been unearthed by a workman.

I had taken Diego out into the street to show him the steps to the ancient cellar that had been found.

But the steps were not the only thing. There had been other interesting finds.

When they had pulled up the street, or what had been left of it, the archaeologists went to work with surveying tools and shovels. They were led by Andres, a former neighbor of ours from Tartu. He was another one of those mythical Estonian men who carried around with him a big personality and yet communicated very little.

Andres was about a decade older than me, a dark-haired, sturdy guy with a square chin. His wife Kärt was a petite woman with a terrific laugh. I would make a droll comment now and then and then she would cackle with her entire body, leaving me to wonder if what I had said had actually been funny or if Kärt was just a bit insane.

Kärt was a brunette, and similar enough in coloring that she could have been Andres’ midget sidekick. But Kärt had an Estonian last name. Andres had a strange last name that had some T’s and V’s in it, and I had heard that his father had been Ossetian, a little nationality wedged in the Caucasus. Andres also had fathered about seven children, three of them with Kärt, but despite this obvious source of stress, he seemed entirely relaxed, and kept a number of pot-bellied pigs in his backyard. During ‘white night’ grilling parties in June, he would take the pigs out and stroke their bellies and grin. That was back in those Tartu days. Sometimes in Viljandi, I did wonder why we had ever left.

Once I had proofread an academic article for Andres. It involved discoveries found in an ancient latrine located just across from the main building of the University of Tartu. Old toilets, as I learned, are goldmines for archaeologists. One can imagine how some Estonian court jester in the Hanseatic days went to relieve himself after a night of dancing and debauchery and dropped his flute into the toilet’s hole. Bloop! Centuries later, Andres showed up with his own gang of merry men and women and found the same instrument encased in the orange-colored clay of the ancient dumping site. According to the article, the flute they found in that old toilet still played. I imagined how Andres had held the precious find aloft in triumph, and then cleaned it out a bit with his muddy fingers, placed it to his lips, and started to play it. When I described this scene, Kärt cackled insanely and said that it didn’t happen exactly that way.

Andres loved his job and I envied him for that. He spent those weeks in our mud hole of a street in Viljandi scurrying back and forth and taking measurements. Each time he passed, I would ask if they had found any skeletons. I was convinced that there had to be dead people under our street. It just seemed like that kind of place.

“So, Andres, have you found any Teutonic knights?”

He shook his head. No knights yet.

“Any Swedish soldiers?”

“Not yet,” he said and trudged on.

I was cautioned by a neighbor about this morbid interest. “God forbid those people find a skeleton,” she had said. “In that case the archaeologists will be digging here for a year! The street will never get done.”

But they did not find any human bones on Sepa Street. There was plenty of trash though. It made Andres’ eyes brighten. There was fog and delirium behind his glasses. And every once in a while, he would come to me to share his special treasures.

“Do you see this beaker shard?” he would hold out a sliver of ancient blue glass in his palm. “This was made in Venice!”

I stared at the shard, trying to imagine how a tiny piece of such a great city could wind up in a hole in Viljandi.

And around the corner, at the end of Munga or Monk Street, Andres said they had found the remains of a potter’s shop. The style of the earthenware matched ceramic shards found in Pskov, a Russian city of 200,000 located 20 km southeast of the Estonian border. It seemed that the potters in Viljandi, the water city, had been trading with the Slavs of Pskov long before any marauding Teutonic crusaders arrived on horseback. Or perhaps a potter from Pskov had gotten in trouble with the local authorities and fled his home to set up shop in quiet Viljandi, a place where it was certain that nobody would ever find him.

There were other curious finds on our street. Some coins, a horse shoe, a stone pendant. And plenty of animal bones.

Even I had my little discovery. I had been raking out a plot of dirt when I turned up a very human-looking jawbone. This led me to all kinds of uncomfortable hypotheses about my neighbors, until Andres came and calmed me and said that it had probably belonged to a sheep.

But the day after brought something truly sinister to the surface – an unexploded mine that had been dug up right next to our barn! You can imagine how happy I was that I had never done any renovation work around there. The newspaper said it had been lying there since the Second World War, and a special bomb unit had been called in to take it away and detonate it. I asked all the old neighborhood ladies I knew, but nobody could remember hearing of any battles on my home street.

Andres didn’t bother himself with such things anyway. They weren’t old enough. But he did find some ancient cellar steps that led straight across Sepa Street. They were formed by huge, rounded boulders, stacked on top of each other by God-knows-who, hundreds, or even a thousand years ago. They went down into the ground and then rose up again on the other side. The archaeologists had marked off the site with a metal fence. They had even brought a video camera to record the dig. Andres said he had been studying maps of the site, drawn by cartographers in the employ of the Polish crown, to which Viljandi and much of southern Estonia had been subject between the 1560s and 1620s. It was one of those periods that only historians bothered to recall, but the oldest, most accurate maps of old Viljandi made by Polish cartographers were actually kept in Moscow, Andres said.

Andres and the archaeologists abandoned their camp when the Viljandi Folk Music Festival came around. But I was impressed enough with the cellar to show it to Diego, my new Chilean friend, that day when he came to visit. And while we were standing there, gazing down into the ancient hole, he had to ask:

“Don’t you go out of your mind with boredom in this hole, man?”

Poor Diego. He was like me. He had come to Tallinn on a whim and met his future wife by chance. Any rational man would have gone back to Santiago and married a local girl named Violeta or Veronica. But Diego was different. He was a romantic. It had been the night before he had to leave and yet he couldn’t forget that Estonian maiden, even in Chile. So he had to marry her and move to Estonia after that.

And so here he was, staring down into some crypt, grateful that he lived up in Tallinn and not down on Sepa Street.

“When you have three kids, you don’t have time to go out to bars or the movies anyway,” I told Diego. “And this place is good for raising kids. I can walk them to school, bike to the shop to pick up some groceries. Our daughters can run to their friends’ houses to play. You can’t do that in Tallinn. Or in New York.”

Diego nodded a bit as if he almost believed me.

“And, I mean, the view of the lake is beautiful,” I added.

“Sure, it is. But do you really want to look at it every damn day?”

A mutual friend told me Diego was having a hard time adjusting to life in Estonia. I knew he had quit working at a graphic design firm, not because of pay or disappointment with the work given him, but because he could not connect with his co-workers for some reason. I bet it wasn’t anything they said or did, but the silence that had gotten into his bones and irritated him from the inside out. Why else would Diego have pulled me aside earlier that summer and whispered, “All the people from this country should be removed and replaced by Brazilians”?

Elias, my Swedish-Estonian chef friend, had stopped working at a local restaurant for much the same reason. He complained how his fellow cook, an Estonian, would say nothing to him during the work days.

“Nothing, not a word. You ask him a question and he shrugs.” It drove Elias to take up work on a cruise ship.

“You still didn’t answer me,” Diego said and put a hand on my shoulder. “How do you cope, man?”

It seemed Diego wanted a longer answer from me. “Look, don’t get me wrong, it’s been really hard,” I confessed.

“What’s been hard?”

“Oh, living here. Everything. You know, I really started to hate the Estonians in my heart. I started to think that they were all just a bunch of Nazis and I didn’t want to have anything to do with them.”

Diego took off his sunglasses and looked up at me. “Man, that is exactly how I feel,” he stammered. “And I thought I was alone. And I’ve had nobody talk to.”

“You can’t exactly tell your wife that her people are a bunch of Nazis.”

“No, I don’t think that would go over too well.”

“But, hey, not all of them are like that, and, whatever, you’ve just got to accept them. I’ve learned that I am who I am and they are who they are, and I might as well just live my life and be happy.”

I didn’t tell Diego that I had been seeing a psychiatrist for years. And whether the emotional temperament of some Estonians had been connected with my depression or not, they had not made my life any easier. Little things would set off my rage. The sight of an alcoholic rummaging through a trash can. The impatience of a person standing behind me in line at the grocery store. I could hear those tight breaths, feel them on my neck because I had bought enough food and drink to last a week, and that person just wanted to buy his ham and cigarettes. Those clicks of the tongue, that nettled sigh that said, “You are inconveniencing me.” In Viljandi, a man would bump into you on a sidewalk, clip you on the shoulder, nearly knock you down, and then grunt and keep on walking, as if nothing had happened. It was all, as they said, normaalne.

Ninety-seven out of a hundred Estonians would be fine to me. But it was those three Estonians, those garbage-picking drunks and pushy shoppers and rude pedestrians, whom I loathed. I knew it was wrong to hate a whole nation just because of the pitfalls of a few bad characters. Estonia had given me everything: a lovely and loving wife, three children, a writing career, a charming house in a rambling old town, stunning lake views, fun anecdotes about medieval toilets, unearthed mines, and sheep bones. On warm summer afternoons in Pärnu the car would cruise down the streets past the most golden, beautiful women you ever saw. You’d go to “Supelsaksad,” the 1920s-style cafe and eat the best meal you ever ate, sit on the most comfortable camel-humped couch you ever sat on, and then head over to the beach to swim in the warmest water you had ever touched and to breathe in the freshest air your lungs ever savored and roll amongst the soft, wonderful sands.

And yet I had grown wary of Estonians, even those ones in Pärnu. Every zombie drunk forager, every heel-clicking bureaucrat. My distaste ran so dark and deep that I eventually determined the only way out was either to run away and desert my family or to succumb to tolerance and accept the locals for being who they were, not because they all deserved it, but because not accepting them was unhealthy and could drive me to do dangerous and unreasonable things.

The way I had come to see it, Estonia wanted you to change. It wanted you to speak its language and think its thoughts. It wanted you to ignore those drunks in the park, and to be more efficient with your shop transactions. It wanted you to grunt and keep on walking when a fellow pedestrian slammed his shoulder into you. And, above all, it insisted that you would never complain about its weather. Even a “Kind of cold today, isn’t it?” would earn you another lecture about wearing warmer clothing.

In the end, to become an Estonian was to kill some Italian-American or Chilean part of yourself, if you had the fortitude or mental discipline to really do that. Most people didn’t. Most foreigners who reached that point went running back to the mother country.

I remembered reading an interview with an American-Estonian businessman who had lived in Tallinn for years. I found it in a celebrity magazine shortly after we had moved back to Estonia. While we were unpacking our bags, the businessman’s family was packing theirs. “Ten winters of this is enough,” the guy said in the story. “We’re moving to Hawaii!”

Back then, I thought Hawaii was for surfers and the weak of mind. I thought I would be tougher than that businessman and others like him.

By the time Diego had asked me his very big question, I thought I had graduated from the most painful parts of the adaptation process. It had been almost seven years since we had returned from New York with our six suitcases, and I thought that I had at last come to terms with Estonia and my relationship to it. I believed that I was emotionally prepared to spend a long time in Viljandi’s watery embrace. The future, as far as I could see, would be more of the same.

Little did I know.