Читать книгу My Estonia 3. What Happened? - Justin Petrone - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

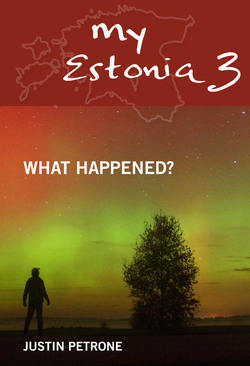

SIX SUITCASES

ОглавлениеYou should know that I returned to Estonia with only love in my heart.

In the cafes and arcades of lower Manhattan, which are haunted by eccentric and deranged characters, like the lady we used to call the “cat woman,” because she was always stroking a feral cat, I felt the long-armed but loving embrace of Estonia, that land I had left behind. Even while the mountains of garbage piled up along the avenues, and the cat woman’s dementia grew worse through the seasons, so that I once saw her with vomit all over her coat and the sidewalk before her, I had that extra bounce in my stride because I knew that I was one of the lucky ones, the ones with alternatives, the ones with another place to go.

In my New York office, I decorated my computer screen with an image of a lighthouse on Saaremaa, the largest Estonian island, and when I grew tired of sighing over the cool water and rocks, I changed it for an aerial view of Tartu’s Supilinn area, those crooked roofs, the orange and red autumn leaves. I would ride satellite maps across the ocean, to see how close I could get to the cozy studio apartment in Tallinn’s Kalamaja district that we left behind when we moved to New York, and though we were so far away and someone else was living there, I would stare at the tiny red roof for a while, and imagine it was me standing in that sunny driveway beside it, and how I would walk down the road and pass the cats at the dumpster and then head on to the local corner shop, to buy a few boxes of tasty Georgian dumplings and a big bag of Kalev chocolates...

Some might have called it “homesickness” but, somehow, I was experiencing this longing in my country of birth.

When Supilinn’s rooftops ceased to soothe me, to console me among the jackhammers and bleating cars and arrogant pedestrians, I found another image of Estonia, a photo of an old farmhouse nestled in green-yellow fields, and put that across my desktop. That farmhouse, the real one in the picture, was from Iceland or Greenland, and it had that Ilon Wikland illustration-like Swedish red, with the white trim around the windows, but in my mind that didn’t matter, because it was my Imaginary Estonian Farmhouse, a place where I thought the greater me, the eternal soul of me, belonged.

One time, my boss Bernadette caught me staring at it.

“What’s that?” she asked. Bernadette was anything you could ever want from an Irish woman, with the big hair and the big laugh and that bright, joyous, contagious sarcasm that all us New Yorkers seemed to have. Bernadette and I used to give each other updates not only on the latest biotech industry rumors but also on the cat woman’s condition if we saw her, taking note of her general deterioration into madness, whether she looked clean or dirty, or if she had gotten sick again. And yet neither of us expressed any regret about her. We had to laugh about it because it was so awful.

“What’s what?” I looked up, blushing.

“That,” she pointed at the screen with a freckled finger. “You keep staring at it.”

“Oh that. It’s my Imaginary Estonian Farmhouse,” I said. “See, there’s the main house, and the barn.”

“So, is that where you’ll be doing your job for us next year?”

“What? Oh, yeah, sure,” I pointed at the wooden dwelling. “I’ll be writing about biotech from there.”

People always want to know the “why” of things, why you did this or that, but the truest, most absolute answer is that we left New York because it was leading us around in circles, and something else was calling us from beyond the sea.

Estonia, Estland, population 1.3 million or so at that time. A speck of marshes and forests on the northern seas, with a few castles and apartment blocks and country estates thrown in for decorative purposes. It was calling us, the same way it had called me with its siren song many years before. Something was going to happen to us in Estonia, and so we had to go there.

But what was it?

We didn’t know that part. Whatever it was, it was strong enough for us to endure the physical and emotional hardships of leaving America.

And that was a true hell. All of that furniture, all of those contracts that needed to be severed, telecommunications devices that needed to be returned, all of the family drama, the grief, the bitterness.

“How could you leave behind New York?”

“Why not? Should I spend the rest of my life renting the second floor of somebody else’s house? And spend three hours every day in the dirty subway train, commuting?”

“You could look for a new job.”

“I have looked for a new job, and all of the others pay less than the one I have.”

“That just can’t be. That just can’t be…”

I have to look out the window now, to stare at a tree or a train, something to forget about the memories. When I think of those months toward the close of 2006 and beginning of 2007, I can only remember the darkness and the rain. Only one majestic moment stands out. That was the night I went for a walk beside the Atlantic Ocean, the night when I learned that we were expecting a new child. The sound of the waves was heavy, and there were a lot of stars in the sky, and it was moist and cool enough that you could see your breath. I stayed out on that ocean beach for a long time that night, staring up into the reassuring cosmos. There were forces in the universe greater than yourself. You just had to trust them. Somebody had told me something like that.

I heard footsteps approaching in rapid succession, the sound of shoes on sand, and then a late-night beach jogger ran past me. Out on the sea, I could see the glow from the ships. I thought about the ship that had run aground once out here, its hold full of illegal Chinese immigrants destined for sweatshops. That was their dream, though, to come here, to New York, the place to be. And I was one of the lucky few who were actually born here. Why did I need to leave?

The waves crashed on the shells, and I watched a plane come in to land at John F. Kennedy International Airport, which wasn’t so far from our house. We had already bought the tickets. It was all done and set. All we would need to do is pack our suitcases. There were three of us and each of us could take two. Six suitcases for lugging one family’s life across the ocean.

But there were actually four of us now, sort of. A new child. Epp wanted to call her Anna. The last time Epp had visited Estonia, she had interviewed her grandmother Laine, and heard more stories about Laine’s mother Anna, a lady who lived in a big house by the sea a long time ago. Grandma Laine was not one to peddle sob stories, but she was not the most uplifting character either. Laine had very light blue eyes and an ancient face. It was a face of cataclysmic geology, that peak of a nose, those ravines of eyes, the patch of snowy white fuzz beneath the chin. She wore a blue handkerchief around her head, and asked you practical questions about the pluses and minuses of life.

But at least one time, Laine gave Epp the full story about what had happened to their family in 1949, how Anna and a teenaged Laine hid in the woods when the Soviet military forces came to arrest them and send them to Siberia, surviving on ants during three long nights in March. So they escaped. A middle aged woman and a teenage girl managed to outwit one of the most bloodthirsty regimes in living memory. There were uglier things, too, but I won’t go into those. What I will tell you is that Anna’s story was a hero’s story, and even when I was standing on that dark, foggy beach, I knew that a new heroic little Anna was coming.

But she wouldn’t be born in New York. Not all children could be born there. Some children had to be born in other places and this child would be born in Tartu.

Tartu, where my sister-in-law and brother-in-law and little troublemaking niece Simona lived, Tartu, with its university where I could continue my studies, perhaps gaining skills that would bring in income, or maybe, if I was truly lucky, I could live the easy life of an academic myself, idling away the hours reading books and grading papers and thinking of ways to spend all of those free days in summer. Tallinn was full of bankers and politicians and professional celebrities who liked to have their personal lives chronicled in the tabloids, but Tartu! It was different. The academic, bohemian oasis was waiting for me.

And so, we put our most important possessions into six bags one night and boarded a plane to Warsaw, and from there to Tallinn, to take the train to Tartu.