Читать книгу Metal that Will not Bend - Kally Forrest - Страница 23

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

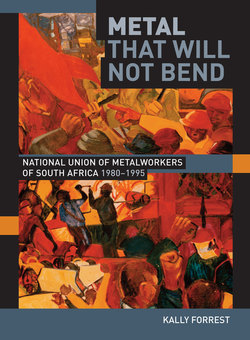

Chapter Four Breaking the apartheid mould: 1980–1982

ОглавлениеThe strike weapon is the cornerstone of union power. Its potency critically depends on its collective character, as individual workers cannot bring a factory to a standstill – and are easy to replace.

Most strikes erupt spontaneously and are followed by union authorisation. In such cases, management has less opportunity to plan a response than it does in official disputes. Wildcat strikes are often, therefore, the most effective way for workers to insist on a say in matters affecting them. Rick Fantasia remarks that solidarity is welded to the act of opposition, forged during the strike itself. Like Hyman, he believes that the spontaneous strike, independent of official bargaining routines, is often most effective in articulating and redressing grievances.1

In the early 1980s, strikes returned in force to South African. More spontaneous strikes broke out on the East Rand in 1981–1982 than in any other period in South African labour history,2 and many of the strikers were not unionised. Mawu, and to some extent Naawu, understood that wildcat strikes could be harnessed to build national worker power. In its appreciation of the power of spontaneous action, it was heir to German socialist Rosa Luxemburg’s theory of spontaneity. She wrote of the Russian revolutionary movement: ‘Its most important and fruitful tactical turns of the last decade were not “invented” by determinate leaders of the movement, and much less by leading organisations, but were … the spontaneous product of an unfettered movement itself.’ She asserted, echoing Vladimir Lenin, that ‘activity itself educates the masses’.3

In metal, there were pivotal disputes which advanced labour’s agenda and which show how power was built in a multifaceted way. These disputes struck at the heart of capitalist exploitation but also ruptured the apartheid mould when grand apartheid was at its height. In different ways, these strikes attacked divisions entrenched by the state. They expressed workers’ newfound confidence and determination to assert control over their working conditions, the fruit of the painstaking organisational work of the 1970s, and the new labour dispensation. These unions, with their emphasis on workers’ control, brought a blossoming of new ideas, demands, tactics and innovative struggles on a scale never before witnessed in the South African labour movement.

At the heart of this creative energy was a dynamic relationship between union intellectuals, union leaders and members. Militant worker action sometimes took union strategists by surprise and was seen as misdirected, but it prompted new thinking and a reformulation of demands and strategies. Such rethinking was often not what workers initially demanded, but represented a refocusing and deepening that struck more directly at the heart of their exploitation. In this way, the unions began to confront deeper restructuring issues with capital. Many struggles were lost or not immediately resolved but remained in the unions’ collective memory, to be returned to later or built on when the opportunity arose. Unions sometimes lacked the resources to cope and yet creative approaches moved their agenda forward and opened up new strategic opportunities which pushed back the frontiers of factory control.

Tarrow remarks on how social movements which are not ‘bound by institutional routines’ give rise to leaders who are highly creative in ‘selecting forms of collective action. Leaders invent, adapt and combine various forms of contention’.4 Mawu and Naawu used a range of innovative tactics, including go-slows, working to rule, grasshopper strikes, trials of strength, demonstration stoppages, consumer boycotts, legal action, sleep-ins, strategic negotiations, community solidarity, house visits, fund-raising strategies and international solidarity. A battery of tactics might be applied in a single dispute, and new ways of sustaining solidarity were devised.

Initially, unionists relied heavily on the element of surprise, using their superior knowledge of labour relations procedures and laws. Then, as employers became more sophisticated, unions were forced to revise their tactics and to view defeat as an opportunity to develop a more effective way forward. The unions’ political independence also gave them the flexibility to respond rapidly and to alter strategic and policy directions without being fettered by external dogmas and bureaucracy. They could debate and freely choose their strategies in consultation with their members, to whom they were alone accountable. It was this freedom to manoeuvre that allowed for such an explosion of innovation.

Strikes enabled the unions to force their way into factories, and every act of defiance, every success, had a ripple effect in spurring on other workers to stand up to their white employers. This increased the size and power of the metal unions, which in the 1980s expanded to every corner of South Africa. Three disputes or waves of contention were central to the rise of the metal unions in the early 1980s: the Volkswagen strike of 1980, the 1980–81 pension strikes and the East Rand strike wave of 1981–82.