Читать книгу Manifesto - Karl Marx - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

armando hart

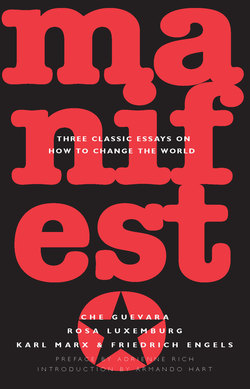

José Martí spoke of the invisible threads linking human beings across history. The publication of these three texts together: The Communist Manifesto by Marx and Engels, Reform or Revolution by Rosa Luxemburg and Socialism and Man in Cuba by Ernesto Che Guevara — all written in vastly different eras: 1848, 1899 and 1965 — will direct the reader to these invisible threads that bring together socialist ideas of the 19th and 20th centuries.

If we were capable of publishing and studying the fundamental texts on the nature of socialism, by a range of authors, we would discover increasingly profound answers to the real causes of the failure of the left in the 20th century. This has become a need that can no longer be postponed, because in the 20th century, following Lenin’s death, the essential principles of Marx and Lenin have been adulterated, whittled away. Humanity cannot advance toward a new type of thinking in the 21st century if the essence of the works of these geniuses is not clarified.

The common essence of these three texts, brought together in this book, is the aspiration of human redemption in “the kingdom of this world,” and achieving this redemption with the aid of science, by raising consciousness and by mobilizing the poor and exploited in the world. These texts represent an indictment of human alienation born out of the exploitation of human by human. Likewise, they have in common the idea that the capitalist system leads, as a result of its own development, to the need to find ways of socializing wealth.

A detailed analysis of these texts allows us to understand in greater depth that, after Lenin’s death, the political importance of culture was not integrated into socialist practice. It was not taken into account by Engels when… he pointed out:

…Civilization has achieved things of which gentile society was not even remotely capable. But it achieved them by setting in motion the lowest instincts and passions in man and developing them at the expense of all his other abilities. From its first day to this, sheer greed was the driving spirit of civilization; wealth and again wealth and once more wealth, wealth, not of society, but of the single miserable individual — here was its one and final aim. If at the same time the progressive development of science and a repeated flowering of supreme art dropped into its lap, it was only because without them modern wealth could not have completely realized its achievements.1

Socialism therefore demands the promotion of the best in human nature, and to this end it is essential to find and utilize the ideas of key cultural figures. It is crucial to select the ideas and thoughts of all the greatest cultural figures from the era of the mythical Prometheus to contemporary times. This can be done using the selective methods of Cuban cultural traditions — methods chosen precisely to find the paths to justice.

We continue to insist that the thoughts of a wise person are not enough on their own to find the path to socialism. Moreover, the infinite wisdom of great socialist thinkers is not enough to open the gateway to these redemptory ideas that, say what you might, are the most profound and sophisticated to emerge from Europe and have acquired the greatest significance over the last two centuries. As we have mentioned to the publishers, we see this book only as a first endeavor toward something more ambitious. We must continue to seek the invisible threads in order to articulate contemporary fragmented culture, or the process of the dissolution of what is known as western civilization.

It is essential to clear away the mysteries of current neoliberal fragmentation — of the anarchy and chaos prevailing in the world — an argument dramatically expressed by Fidel Castro on the 45th anniversary of the Cuban Revolution: “Either the course of events must change or our species will not be able to survive.”2

As Cubans we can grasp the essence of universal culture expressed in these texts because we have been able to perceive what has transcended from them. This is fundamental for humanity today. That we are able to interpret it within a contemporary context, on the basis of the teachings and traditions of major figures from our history, of whom José Martí is the most outstanding, is due to our experience of the revolution of January 1, 1959. In other words, we have 45 years of practice in confrontation and struggle against the most powerful empire in the world.

Moving in chronological order, I want to set out what I consider to be the key aspects of the documents we are presenting to the reader.

The first of these is, naturally, The Communist Manifesto, written, as is well known, by Marx and Engels in 1848. It begins with the famous words, “A spectre is haunting Europe…,” to which I might add: this spectre has remained at the center of history for 150 years. We could also state that since 1848 no political event has been without direct or indirect relation to the fire of ideas and feelings which this text evoked. In one way or another, the text has been present in the historical subconscious of western civilization, either to support or to undermine it. Of even greater importance is that it has been present, over the past 150 years, in the interweaving of redemptory ideas and aspirations that have been at the heart of western civilization. What we have to ask ourselves is whether humanity is capable of forgetting, of pushing to the side, the hopes and emancipatory aspirations that are framed by the communist ideal.

The Manifesto was written to describe and denounce the capitalist social regime in mid-19th century Europe. No political document written since has achieved this with such depth and clarity, or so faithfully expressed the revolutionary needs of its historical period. It described with scientific depth and literary quality the essence of social and economic history since remote antiquity up to its time; and no other document of its kind has improved on its analysis. Without the lessons it provides, the subsequent development of history in the second half of the 19th century and the whole of the 20th century could not be understood.

During the trial of those involved in the July 26, 1953, attack on the Moncada garrison, the state prosecutor accused Fidel Castro of being criminal for the fact of keeping books by Lenin in the apartment of Haydée and Abel Santamaría.3 Fidel responded: “Those interested in politics who have not read and studied Lenin are ignorant.” Moved by Fidel’s words, I resolved to embark upon an in-depth study of Marx, Engels and Lenin. After more than 50 years, I can say that those interested in politics who have not read The Communist Manifesto of 1848 are also ignorant. Those who, like Fidel, study it and learn from its teachings, and at the same time embrace the cause of the poor, will find the path to revolution.

Reading The Communist Manifesto, with the benefit of experience acquired through events of the past century and a half, we can see that the authors not only described profoundly and concisely the historical period in which the text was written, they also provided invaluable teachings for the world in which we live today.

The reader, by viewing humanity’s development since then through the key lines in the Manifesto, will see that capitalism has continued to march toward taking control of the surplus value created by human labor, which it still extracts from workers. The theft has continued, it is more widespread and has been carried out in a more dramatic fashion. To the extent that we are capable of making an abstraction without prejudice, it enables us to interpret the concrete facts we have within sight and confirm that capitalist society is jeopardizing the relations of production that the system itself has created.

It is clear that modern bourgeois society, which has emerged from the ruins of feudal society, has continued to march forward amid the contradictions and antagonisms that it generated and never abolished. Instead, all it has done is to continue substituting the old conditions of oppression; it is evident that socioeconomic antagonisms and the exploitation of human labor have become increasingly threatening to humanity’s future on earth. It may be demonstrated that wherever bourgeois power has existed, it has continued to transform the relations of production into an alienating factor that makes individual freedom a simple commercial asset. It has substituted the numerous structured freedoms with inhuman and soulless market freedoms. Put simply, instead of exploitation clouded by political or religious illusions, bourgeois power has continued to establish open, direct and brutal exploitation.

Doctors, legal experts, priests, poets and scientists have, over the past 150 years, become its paid servants. It has continued to wipe away the emotions and feelings that in the past have characterized social relationships, reducing them to simple financial relations. Likewise, it will be understood that the bourgeoisie cannot exist unless it is to transform unceasingly the instruments and relations of production and, consequently, social relations in general. It has continued to eliminate all that is simple and timeless, all that is sacred it has made profane, and human beings have been compelled to analyze the nature of their real social relations.

Study The Communist Manifesto as though it were a valuable historical document giving the background necessary to gain insights into and better confront the realities of the present and the future. Compare it with what has happened in the past 150 years and the reader will see that essential truths in the text have been confirmed and exemplified in increasingly dramatic ways by life itself.

Let us see: If this study has been carried out in an unbiased fashion, it will reveal that the course of social and political events confirms that to the present day, the history of society continues to be a struggle between oppressor and oppressed, engaged in eternal confrontation, sometimes veiled, but otherwise direct and open. There is a crucial warning here for all human beings inhabiting the earth and particularly for those involved in making decisions: these struggles have always ended with the victory of one or other of the belligerent classes, with the revolutionary transformation of the entire society or with the collapse of the classes involved in the confrontation. This idea torments us and is the key question in the world of the 21st century.

In short, The Communist Manifesto invites us to reflect on the truths it sets out. With this in mind, those who have read this famous document should read it once again. If you have not yet done so, read it for the first time. You will always find it a useful guide to understanding the historic drama of exploited peoples and as a lesson in the struggle for human and social emancipation.

We can say today, paraphrasing Engels, that The Communist Manifesto is one of the greatest documents ever written in support of the poor of the earth in favor of their struggle for liberation. We could begin to discuss his ideas using the profoundly ethical thinking of José Martí, when he said, in relation to Karl Marx: “He deserves to be honored for declaring himself on the side of the weak.”4

Let’s move on to comment on Rosa Luxemburg’s text. From an intellectual point of view and particularly within the terrain of social sciences, history and philosophy, she is one of the most outstanding women in the world and among the elevated intellectuals of the human race. With her assassination on January 15, 1919, the right wing demonstrated its powerful class instinct and proved that it was more aware of the caliber and significance of unswerving revolutionaries than many who proclaimed themselves as such.

Rosa fought equally against reformism as she did against dogmatism, meaning that she made enemies among dogmatists and reformists. As it was both sides that imposed themselves on the evolution of socialist ideas in the 20th century, the illustrious adopted daughter of the Germany of Marx and Engels was smothered under the tapestry of false interpretations of these founding fathers’ work.

Much was lost to the world revolutionary movement with the assassination of Rosa Luxemburg and the marginalization of her luminous ideas. Until now we have been arguing the importance of the subjective factor in history, in a progressive sense. The dramatic reality of contemporary times has shown that this same factor also impacts negatively as a painful historical lesson. In relation to Rosa Luxemburg’s ideas, we have a sound judgment to make in this respect.

In this text Rosa criticizes reformist statements from a dialectical perspective and in terms that are logically rigorous. She points out how positions originating from these statements exacerbated contradictions between the rich and the poor and led to the need for a social revolution. The 100 years that have passed since she wrote this text demonstrate that reformism, far from succeeding, helped to universalize anarchy, wars, brutal conflicts, and even to expand terrorism throughout the globe, creating the particularly grave situation we currently face in the world.

The basic argument put forward by reformists in the times of Marx, Engels and Lenin and, consequently, in Rosa Luxemburg’s era, stated that capitalism could cushion and even overcome class differences with measures such as the following:

- Improvements in the situation of the working class

- Extension and broadening of credit

- Development of the key means of transport

- Concentration of the trusts that accentuated the tendency toward the socialization of the means of production

For reformists, these processes would blunt the class contradictions that would lead to social upheaval and, therefore, to a revolution against capitalism. The position set out by Rosa Luxemburg was that these processes could slow down or delay and, as a consequence, lengthen the workers’ struggle, but that in the end social chaos was inevitable.

How are the weaknesses of these reformist theses manifested? If capitalists were people without petty ambitions and were educated, or at least had common sense, the ideal situation would naturally be a process of reforms. Yet this doctrine fails because, as Martí said: “All men are sleeping dragons. It is necessary to rein in the dragon. Man is an admirable dragon: he has been given his own reins.” The key then is in the triumph of common sense, intelligence and culture. We Cubans know this because of our ethical, juridical, social and political traditions of universal value.

What is certain is that the failure of reformists is due not to the possible logical value of their statements, but to the objective fact that the petty and short-term interests of the owners of wealth prevail over more elemental truths than logic. Moreover, these essential truths that, as I say, are rooted in common sense, will lead them to consistently apply reformist ideas; but the [reformist] process will not take place because evil, mediocrity and petty interests rule in the minds of the principal owners of wealth.5 All social systems have disappeared on account of this mixture of stupidity, mediocrity and evil.

In another of her works known as the Junius Pamphlet, Rosa Luxemburg formulates a political slogan and historical choice that faces humanity: socialism or barbarism. More than 80 years after her death, history has dramatically proven her to be correct.

Today’s dilemma is that, for the time being, barbarism has imposed itself. It can only be substituted, from our perspective, by a line of march that, in the final analysis, leads to socialism.

Today we live in a world that is described as globalized; I say globalized because of what the Spanish writer Ramón Fernández Durán called the explosion of disorder. A revolutionary process must take into account objective and economic factors, but it must also consider the cultural and moral questions involved. The basic error of 20th century Marxist interpretation, after Lenin, was precisely in neglecting this key element in political practice.

Finally, we will deal with the well-known text by Ernesto Che Guevara. An analysis of this allows us to explore Che’s central idea: the role of subjectivity and, therefore, of culture in socialism and the education of the new human being.

Socialism and Man in Cuba encourages us, as the most recent of the documents published here, to reflect on the challenges facing socialism. In this text, an embryonic analysis of the superstructural and subjective factors in relation to the material base of socialist society is presented. Hence, it continues to be a key text which contemporary revolutionaries must study in depth.

In this text, Che broaches the crucial question of the ideological, political, moral and cultural superstructure and its relations with the economic base in the specific Cuban situation of the early years of the revolution. He highlights that socialism was only infant in terms of the development of long-term economic and political theory. All that he outlined was tentative, he stated, because it required subsequent elaboration, which did not happen. In an era when material incentives were promoted to achieve social mobilization and intensify production, Che insisted on means and methods of a moral character, without neglecting the correct use of material incentives, particularly of a social nature.

This is, precisely, the Cuban Revolution’s contribution to socialist ideas and it does not contradict the ideas of Marx, Engels and Lenin.

Forty years ago, he raised the problem of direct creation, in other words, the immediate results of humanity’s productive activity. Today, we must study Che’s ideas and suggestions from a broader and more general perspective of culture.

Over four decades later, the matter of subjectivity and, therefore, of ethics, is revealed to us in a more complete and defined way. Today it is inseparable from Fidel Castro’s proposal to attain a comprehensive level of culture in society. The culture of emancipation and accordingly, Che’s ideas on subjectivity, are of immediate interest in our process of revolutionary analysis of the influence of culture in socioeconomic development. This is the only way to find the path that leads to new philosophical thinking and to political action in tune with the contemporary situation.

Determining the influence of culture in development is fundamental to elaborate the ideas needed in the 21st century, especially in the Americas. To test the importance of culture in the economy is an unavoidable commitment we have with Ernesto Che Guevara. This would demand a more detailed analysis, but for now we are going to refer to the matter that Che raised, that of subjectivity. To carry out this analysis, one has to begin with the question of culture and its influence on the history of humanity. This matter has remained pending in the history of socialist ideas during the 20th century.

Let me discuss, by way of a conclusion, some reflections on the role of culture. I will do this by beginning with the history of civilizations in order to reach later more concrete conclusions. A starting point would be the opinion that in the history of civilizations, the theft and misrepresentation of culture has been the principal maneuver of the exploiters in order to impose their selfish interests on others. If this is not understood then the essence of the problem is not understood.

The introduction of the social question as the essential theme in culture is relatively recent in the history of our civilization. It was precisely Marx and Engels who, with great coherence and rigor, placed this question at the forefront of western thinking.

Until then, philosophy had existed in order to interpret the world, but from Marx and Engels the argument emerged for the need to change it. There is no philosophical and practical conclusion of greater importance for humanity in its millennial history. On studying the documents we present here, the reader will therefore understand that we have published them with the essential aim of encouraging a search for ideas that will be useful in finding the paths to revolutionary transformation.

In order to achieve this, we must begin with the authors’ own logic; otherwise we will not be able to discover what their contribution was and where the essential limits to all human achievements are. This is about appreciating an undeniable cultural value. We come across major difficulties. Both the practical application of Marx and Engels’ thinking over recent decades, and enemy propaganda about their ideas — the vision of a closed doctrine with roots in rigid philosophical determinism — was imposed on the consciousness of millions of people. Those who, from the conservative or reactionary ranks, refuted Marx and Engels’ thinking, accusing them of just these same tendencies, or those who also, consciously or unconsciously, attempted to do so from beneath revolutionary banners, were guilty of the same mistake. The only difference is that the former have been more consistent in their interests than the latter.

The philosophical essence of the renowned writers of these texts is, precisely, the exact opposite of dogmatic rigidity. It is really paradoxical that philosophical thinking will only free itself from the vicious circle it is trapped in when Marx and Engels are studied and interpreted in a manner radically different from that prevalent in the 20th century, after Lenin’s death. In other words, when their thinking is approached as “a research method” and as a “guide to action” that does not aspire to reveal “eternal truths” but to orienting and encouraging the social liberation of humanity on the basis of the interests of the poor and exploited of the world. Those who followed this route in 20th century history generated real social revolutions, as in the case of Lenin, Ho Chi Minh and Fidel Castro. Those who interpreted Marx and Engels’ works as irrefutable dogma did not attain these heights; on the contrary, they made them into lifeless texts remote from reality.

An important lesson that can be learnt from this is that the value of a culture may be gauged by its power of assimilation and capacity to excel in the face of new realities. The ideas of intellectuals in all the sciences, including those of a socio-historical nature, are of no value on their own. Their value lies in their potential to discover, on the basis of new findings, new truths. The highest levels of thinking and significant new ideas are cornerstones of the building humanity is constructing in the history of culture, whose foundations are constantly moving and experiencing change. They are not the building, but the key to opening its doors and orienting us toward its interior. Their importance lies in resisting the test of time and retaining a value beyond the immediate, because they manage to synthesize the elements necessary to satisfy needs in social and historical evolution. They are changing the way in which they appear. Those who have contributed to science and culture have done so because they have been able to weave what is new into the tapestry of history.

All cultures that engage in an exploration of the ideal of justice among human beings, if this is done so in depth and with rigor, will penetrate human consciousness and find one of the keys to universal history.

To promote the redemptory ideas contained within these texts it is necessary to study what has turned out to be different from the suppositions on which the ideas of Marxism, outlined in these pages, were founded. Their evaluations were essentially grounded in European reality. Nothing other than this could have been demanded from them. The best of European revolutionary thinking in the 19th century did not arise from a Eurocentric vision.

The expansion of the United States and its ascent to become a powerful capitalist country following the War of Secession [Civil War] on the one hand, in addition to the mass migration from the Old World to North America in the final decades of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century on the other, were historic milestones allowing us to grasp the scope and form that these phenomena would subsequently assume.

If we study a letter from Marx to [Abraham] Lincoln, his hope that the outbreak of war between the North and South would become a step toward a future proletarian revolution in that country is apparent. This did not happen. The European pressure cooker did not explode, among other reasons because the potential labor force in Europe found new markets in North American territories at the end of the 19th century and during the course of the 20th century.

Friedrich Engels said that Hegel’s most important discoveries were due to the degree of his knowledge of his era and that his limitations were also appropriate to his times. It has to be pointed out that the vast knowledge in 19th century Europe, which we admire as one of the highest pinnacles of western culture, was ignorant of and did not ever value the United States, much less the growing revolutionary potential of Latin America.

The following thoughts by Engels are very illustrative of this: “The social and economic phases that these countries [referring to the Third World] will also have to go through before attaining social organization cannot be, I believe, anything other than the object of quite idle speculations. One thing is certain, the victorious proletariat cannot impose happiness on a foreign people without compromising its own victory.” This lesson has been proven dramatically in the reality of the very heart of the old continent.

Marx and Engels did not take into account the imperialist phases studied by Lenin, nor were they sufficiently well acquainted with the socioeconomic realities facing Third World countries. Neither was the founder of the October Revolution able to study our continent, although his analysis of imperialism focused on the main problem of the 20th century, and was based on information he had acquired on the liberation process that was developing during that period among the people of Asia.

The rescue of the best traditions within universal culture is an undeniable means of defending the interests of the poor. It is should be compulsory to carry out concrete economic studies that help us demonstrate reliably that culture has been the most dynamic factor in the economic history of the world, and particularly the world within which we are living.

In order to explore the question in some depth I suggest following the thread linking these documents historically on the basis of José Martí’s most central ideas. When we read Martí, we begin to notice a more detailed analysis of the reasons why socialism failed. He was fulfilling the role of prophet when he warned of the following:

There is something I must praise highly, and it is the affection you show in your dealings with people; and your masculine respect for Cubans, whoever they might be, who are out there sincerely seeking a world that is a little better and an essential balance in the administration of this world’s affairs. Such an aspiration must be judged as noble, regardless of whatever extremes human passion might take it to. The socialist project, like many others, involves two dangers: readings that are confused and incomplete, distancing the project from reality; and the concealed pride and anger of the ambitious, who make pretences in order to get ahead in the world, to have shoulders to hoist themselves on, frenetic defenders of the helpless. Some go like pests, the queen’s hangers on, as was Marat when with green ink he dedicated his book to her, bloody flattery, Marat’s egg of justice. Others go like lunatics or chamberlains, like those Chateaubriand spoke of in his Memoirs. But the risk is not as great among our people as it is in those societies which are more wrathful, where there is less natural light. Our job is to explain simply and in detail, as you know how to: it is not to compromise sublime justice by using flawed methods or making excessive demands. And always with justice, you and I, because mistakes that are made do not authorize those with good souls to desert in its defense. Very well then, there it is, May 1. I anxiously await your account.6

Martí represents a humanist vein from within a radical tradition. His originality lies in the fact that he was radical and at the same time determined to gather the largest number of people possible in support of the cause he had in mind.

Very often human beings have been radical and have not made a sufficient mental effort to unite all those who could potentially support them. On other occasions they have endeavored to unite large numbers of people without being radical. Martí was radical and at the same time promoted a policy aimed at overcoming the Machiavellian principle of divide and conquer, replacing it with the postulate unite to win.

At this point we touch on an essential matter within the Cuban intellectual tradition: the role of culture and ethics in society. On the philosophical plane, Martí pointed out ideas that could lead to a crucible of principles of major political significance, practice and teaching: the balance of the world / the still uncertain balance in the world,7 the utility of virtue8 and the culture of making politics.

Faced with the demagogy and evil intent of those who govern the United States — those who have spoken of an “axis of evil” that includes Cuba — we could reply that it is necessary to strive toward an axis of good that consists of culture, ethics, law and political solidarity. With that framework and in the context of the Cuban Revolution, we have read and assimilated these documents that have transcended their historical times to become a vast source of wisdom, without which it would be impossible to understand our historical times and the future of the 21st century.

Armando Hart

September 2004

1. Friedrich Engels, “Chapter IX: Barbarism and Civilization,” The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, at: http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1884/origin-family/ch09.htm.

2. Fidel Castro, Granma (Cuba), January 5, 2004.

3. Haydée and Abel Santamaría both participated, along with Fidel Castro, in the July 26, 1953, assault on Fulgencio Batista’s Moncada army garrison. Abel Santamaría was brutally tortured and killed in the days after the attack. Haydée Santamaría was imprisoned along with other survivors.

4. José Martí, “The Memorial Meeting in Honor of Karl Marx,” José Martí Reader: Writings on the Americas, (Melbourne and New York: Ocean Press, 1998), p43.

5. José Martí, “Comentario al libro de Rafael de Castro Palomino,” Obras Completas, (Havana: Ciencias Sociales, 1993), p110.

6. José Martí, “Carta a Fermín Valdés Domínguez,” Obras Completas, p168.

7. José Martí, “Manifesto of Montecristi,” José Martí Reader: Writings on the Americas, p185.

8. José Martí, “Ismaelillo,” Obras Completas.