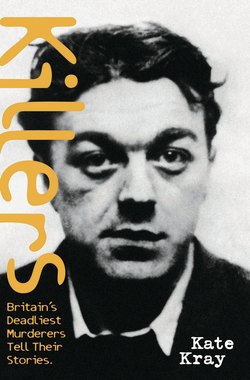

Читать книгу Killers Behind Bars - Kate Kray - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Meaning of Life

ОглавлениеIt’s like being on another planet … that’s the only way you can cope with it. I had to forget about my life before and think of it as being taken away from the world I had always known and put into another world. A world that was completely alien to me. A strange world of different noises, different smells. It’s an unnatural world, a one-sex world and it’s an unnatural life to be locked away 24 hours a day, every day. You know you’re never going to be able to do simple things like swim in the sea or walk under the stars again. You know that from now on you don’t think for yourself, or make any kind of decision for yourself, you’re told what to do and when to do it. ‘Please, Sir, can I do this? – please, Sir, can I do that?’ You know that’s how it’s going to be for the rest of your life – my life …. If you can call it a life. I think it would have been kinder to hang me.

That was how one of the lifers I spoke to described his life sentence to me. I suppose in a way he was right. Now, every time I drive past a prison and see those high stone walls, I think of the prisoners who are kept there and think of it as just that – another world. A completely unnatural alien world. It doesn’t take a genius to work out that if you lock a thousand men in one building for years on end it’s going to be like an unexploded bomb just waiting to go off … A world where a simple sausage can start a riot…

I was standing in line waiting to get my breakfast. There had been some delay in getting the hotplates on to the wing and the time allocated for breakfast was nearly over.

‘Get a fucking move on,’ one of the screws snapped as he shoved me hard in the back.

I fell against another con who was standing in front of me.

‘’Ere, watch what you’re fucking doing,’ he said. ‘Look, you made me drop my sausage.’ The half-cooked sausage rolled across the filthy floor, among the fag-ends. The con held out his small metal tray for another one.

The screw serving food said, ‘Sorry that was the last one, there ain’t any more sausages.’

A deathly silence fell along our line. ‘Wot, no more sausages!’ someone gasped. ‘I ain’t having that – I’m entitled to a sausage and I want my fucking sausage and I want it now!’

The screws, leaning against the wall chatting, looked over and one snapped, ‘Never mind about sausages, move along.’ The con was determined, he banged his tray on the hotplate and shouted at the screw, ‘I ain’t fucking moving – I know my rights!’

Things were turning ugly and the screws started moving in. Crack!! The con who had lost his sausage turned and whacked a screw with his metal tray, breaking his nose. Quickly, alarm bells were pressed and an almighty fight broke out. The screws scrambled out of the wing as quickly as they could, locking us inside. We responded by barricading the doors and rampaging through the wing, smashing tables and chairs and anything else that got in our way. It was just sheer frustration bubbling out. It was like a shaken-up bottle of Coke and someone unscrewing the lid. The pressure was explosive! Nothing was going to stop the flow. We smashed everything we could lay our hands on. Nobody really knew why we were doing it. We just were. It felt good to be in control again, but it didn’t last for long. We knew our newfound freedom would be short-lived and every one of us knew the consequences.

After a couple of hours, we had smashed all there was to smash and shouted all there was to shout. We had burnt ourselves out and none of us knew what to do next. We were all sitting around among the debris, smoking and chatting, when the governor appeared at one of the barricaded doors. ‘All right, you’ve made your point, come out now and nobody gets hurt.’

Someone shouted, ‘Go fuck yourself, you old git’, and we all roared with laughter.

The governor shrugged his shoulders and gave the nod to the riot squad who were standing directly behind him. They looked like something out of a science fiction film, with their full facial helmets, big batons and riot shields. Believe me, they meant business. Within seconds they had stormed the wing and were kicking the shit out of us. We didn’t stand a chance. Some of us ended up with broken noses, dislocated shoulders, cracked ribs, and the wing was completely destroyed. And all over a sausage …

To you outside it probably sounds ridiculous, but that’s how it is in prison. It’s not the soft, cushy place that the media try to make out. It’s a tough violent, brutal place. You have to fight every day – just to survive.

Christmas is the worst time. That’s when you feel it the most. You miss your family so much the pain inside you cuts like a knife. Or when someone gets a ‘Dear John’ letter, which often happens with long-term prisoners. It affects the whole wing. You can’t go and talk to your wife and sort it out; you just have to swallow and brood on it.

In writing this book, I spent many hours talking with lifers and they all seem to have the same look in their eyes – a look of despair and regret, a look that cries out: ‘If only…’

Sitting, talking with them over a cup of tea in the visitors’ hall, I often found it hard to believe that these people really had committed the horrific murders they were so calmly telling me about.

None showed much remorse for what they’d done, in as much as they were sorry and guilty for having stolen someone else’s life, but they all regretted their crimes – because it meant a life in prison for themselves…

There’s been a lot of political talk recently about life really meaning life, but the cons would argue that a life sentence already means just that. It stays with them until the day they die. It can never be revoked.

A life sentence is divided into four parts: security, training, assessment and, finally, preparation for release.

Prisoners are often moved from prison to prison. The authorities don’t like them to get too settled and it is thought that too long in one prison can be detrimental for the lifer. Everyone needs stimulation and challenge and changing prisons at regular intervals can, they believe, help to provide this.

Stage One

Once they have been given a life sentence, all prisoners are allocated to what is known as a main centre prison. For men, that’s currently Wormwood Scrubs in London, Gartree in Leicester, or Wakefield.

The small number of women lifers are usually sent to Durham H Wing, which is a small, secure unit that holds up to 40 women at a time. The unit is inside Durham men’s prison. Or they are taken to Bullwood Hall in Essex.

The ever-increasing number of youngsters (under the age of 21) serving a life sentence are sent to Aylesbury, Swinfen Hall and Castington. These main centres are lifer-only units and are meant to give the lifer a chance to settle down and come to terms with their offence and their sentence. It also gives the screws a chance to carry out an initial assessment and to decide if the prisoner is a risk to himself, other inmates or to staff.

After sentencing, you receive your tariff date. This is the length of time you must serve in order to meet what is called ‘the punishment and deterrence’ set by law. In all cases you must complete your tariff date before you’re let out. However, your case will be looked at by the Local Review Committee before that, usually three years before your tariff date.

Tariff dates vary. My brother-in-law Reggie Kray, for example, didn’t have a tariff date because he received a recommended sentence. The same is true of Harry Roberts. He has to serve a recommended 30 years, so the tariff system will not apply until he has completed his recommended sentence.

Stage Two

This is usually the longest part of the sentence and is mostly served in more than one prison. If you’re considered a high-risk prisoner, then you are sent to a dispersal prison. These are the more secure prisons.

If not a high-risk prisoner, you are sent to a Category B training prison. These prisons have a more relaxed regime but still within a secure perimeter. Cat. B prisons are not only for lifers. Other inmates will be serving much shorter sentences. These men will all have a release date and may be allowed parole and home leave. This can cause problems for the lifers. They often strike up a close friendship with these other inmates, so they find their departure hard to take. That, in turn, can cause frustration and resentment – and sometimes trouble.

Stage Three

After many years in a Cat. B prison, the move to a Category C is normally the most difficult. For a long time the lifer has probably been looking forward to the day when he will eventually be moved to a Cat. C, because, as he sees it, he’s finally on his way out. It is a big step forward.

Cat. Cs are much less secure and have a lower level of supervision, although still within a secure perimeter. However, the lifer can face new problems. The inmate population will be a lot younger than most lifers at this stage in their sentence and they tend to be serving much shorter sentences. In a Cat. C prison, the lifer is expected to adjust to the pressures and stresses of life on the outside. He also loses all the privileges that he has become accustomed to in other prisons, while release is still an uncertainty. He sees other Cat. C prisoners enjoying home leave and looking forward to their release date but the wait for the lifer is endless. He still has to undergo many reviews and reports before there is even the prospect of a move to a Cat. D.

Stage Four: Category D, release phase and PRES hostel.

Under no circumstances can a lifer proceed to a Cat. D without the approval of the Minister of State for Prisons, and that’s only given after a recommendation from the Parole Board.

After settling in to a Cat. D prison, the lifer may be taken on supervised days out. These become more and more frequent, until the lifer has built up confidence and trust. Then, and only then, is he allowed unsupervised days out and allowed to work outside the prison.

Security at Cat. Ds is kept to a minimum and, essentially, the lifer is his own gaoler. After a specified number of days out without any problems, and when all the reports have been satisfactory, the Parole Board and the Home Secretary eventually agree that the lifer can be given a provisional release date.

This is usually preceded by a period of six to nine months at a Pre-Release Employment Scheme hostel (PRES). While he’s at the hostel, the lifer is expected to find a job and will have to save the best part of his wage to show that he can cope on the outside. Once he has complied with all the rules, and only with approval, he will be allowed weekend home leave.

Stage Five: life licence.

After many years in prison, and only after long consideration by the Parole Board, a lifer may eventually be allowed out of prison for good. This will be on licence and under the strict supervision of the Probation Office. However, the final decision to release a lifer does not come from the Parole Board; they can only submit a recommendation for release. The final word comes from the Home Secretary.

If, and when, you’re finally let out on licence, you are still not free in one sense. You have to report to a probation officer once, maybe twice, a week in the beginning. You also have to ask their permission to do anything like move house or change your job. You can’t go abroad on holiday or have any association with known criminals.

If you are lucky enough to find a job, your probation officer may insist that you inform your employer that you’re ‘out on licence’. In some cases, if the crime you committed was a particularly violent one, you may have to tell the employer the nature of the crime: then it’s up to him if he still wants to employ you. If, as a lifer, you start to become personally or romantically involved with someone, your probation officer will want to meet the person and, if you haven’t already told them that you are ‘out on licence’, the probation officer will.

A detailed report on your progress is sent to the Home Office every three months. If your probation officer or the Home Office is not happy with your progress, you can be recalled to prison at any time.

For this book, I interviewed ten lifers. All of their stories are different. Some are sad; some are just downright brutal. I didn’t write this book to justify or condone in any way what they did nor to say that they shouldn’t be punished for their horrific crimes. On the contrary, I don’t think murder should go unpunished. What interested me was the truth – as they saw it – of what happened – not the newspaper stories or the gossip but the real story behind the story. I don’t think it’s my job to judge them – they’ve been judged already. All I am trying to do here is tell you their stories as they told them to me.

It was my brother-in-law Reggie Kray who first introduced me to Harry Roberts in Gartree Prison in 1988. When he was interviewed for this book Harry had been in prison for 28 years for killing three policemen but, in all, he spent 33 years and seven months of his 58-year life in some of the toughest prisons in Britain, although to see and speak to him, you wouldn’t think it.

Harry is a very intelligent, astute man who keeps himself up to date with the outside world in every aspect. After serving so much time in prison, though, there isn’t anything he doesn’t know about the system. He says: ‘Don’t matter how much you “hoot and holler”, you will never beat the system.’

If anybody should know, Harry Roberts should – he’s an expert. Harry first went to prison in 1954, before I was even born, when prisons were tough. He told me that back in the 1950s prisoners weren’t allowed to talk, and a deathly silence hung over the cold, wrought-iron landings. In those days the food was slop; you were only allowed one egg a year, at Easter, and your one treat was Christmas Day when there was fish and chips for dinner.

‘They didn’t muck about with ya in those days,’ he told me. ‘They would birch ya or give ya the cat-o’-nine-tails or, if ya murdered someone, they would simply hang ya!’

Harry has the dubious honour of being Britain’s longest-serving Category A prisoner. Being a Cat. A prisoner for more than 20 years means that Harry was considered a high risk and treated accordingly. He was monitored 24 hours a day, something which not only affects the prisoner but also his family and friends. For instance, if someone wants to visit a Cat. A prisoner, the prisoner must first ask their wing officer for an application form so that the visitor can be included in their list of approved visitors. The visitor must fill in their full name, address, occupation, phone number and relationship – if they are not a relative then they will have to state how and when they came to know the prisoner. The Governor will then write and ask if the person wishes to visit and the visitor will have to send two passport-sized photographs to the prison. Once the prison has received them, they will ask the police to go to the visitor’s house and check that the photographs are valid. After all that, and for security reasons, visits with Cat. A prisoners take place in a separate room, in the presence of two officers.

At Broadmoor and Rampton security is slightly different. The forms are still sent to the visitor’s home and still have to be approved by the Home Office, but the photographs are taken at the hospital. All the visitor’s personal information is then put on a special card, a bit like a credit card. After that, each time a visit is made, the visitor must produce the card or entry will be refused.

In 1992, card phones were introduced in most category prisons. Using their earnings or private cash, prisoners are allowed to buy these special Prison Service phone cards from the prison canteen. Of course, for lifers who have been locked away for a long time these new card phones were amazing! Ordinary phone cards are no use as prison phones don’t take them, nor in-coming calls for that matter.

In most prisons, phone calls are only occasionally listened in to by the screws, and this is done at random. If you are Cat. A, however, the calls are always listened to and are also sometimes tape recorded. Cat. A prisoners may only call a telephone number on their approved list, once again only after stringent checks have been made, and all Cat. A calls have to be pre-booked.

The governor of each prison sets a limit on how much a prisoner can spend each month on phone calls and prisoners are normally only allowed to buy two phone cards at one time, but this does vary from prison to prison.

In all the years Harry Roberts has been inside, he’s tried to escape – and failed – 22 times. That’s why I was very embarrassed when, on one of my visits to Harry, I took him a present. I had asked Harry if there was anything I could get for him and he had said that he would like a track suit – large size and preferably a dark colour like navy blue or black.

I searched high and low for a plain track suit and couldn’t find one but I did find a really great navy blue track suit with a broad yellow stripe down the arms and legs. Harry was very grateful. When he took it out of the bag in the visitors’ hall, however, he howled with laughter. ‘It’s a fucking escapee’s track suit!’ he said. Only then did I remember that prisoners who persist in trying to escape are made to wear a suit with wide yellow stripes down the side, presumably so that the screws can spot them easily, especially if they’re clambering over the wall!

I offered to change it but Harry wouldn’t hear of it. Even so, I’ve never seen him actually wearing it!

Harry helped me a lot in writing this book. It was while Harry was in Long Lartin Prison, that he introduced me to Colin Richards.

I had just finished writing Harry’s chapter when he phoned and asked me if I needed anyone else for this book. He sounded upset and that wasn’t like Harry who is normally so cheerful. I asked him what was wrong.

‘I thought I had problems,’ he said. ‘Well, I’ve just come out of the cell of a bloke here who’s in a wheelchair. Problems! I don’t know the meaning of the word!’ Harry explained to me how bad it was for Colin – he said he couldn’t even turn his wheelchair around in his cell. ‘He can’t go to the TV room because it’s on the top landing.’ Harry said it was bad enough spending the rest of your life in prison but to be in a wheelchair and still be a lifer was a nightmare.

Harry told Colin about my book but at first he didn’t want to take part. He had been in prison for ten years and had been suffering from deep depression so he didn’t want to talk to anyone. A week afterwards, he changed his mind. Later, he told me that the only reason he had agreed to talk to me was that for the ten years he had been away he had always had the same number sewn into his property – 394 – and he thought that maybe, in the third month of 1994, things might change for him. It must have been fate because Harry Roberts was at a different prison at the time and was only moved to the same prison as Colin for one month, the third month of 1994. If Harry hadn’t moved, I would never have met Colin. So maybe there was something in Colin’s prediction – who knows?

My journey to Long Lartin Prison in Evesham was a nightmare, after three of my trains were cancelled. Eventually, I met Colin Richards on a cold, wet afternoon in March 1994, and that visit will always stay with me.

Patiently, I waited for prison wardens to bring Colin into the small, grubby visitors’ hall. Harry Roberts joined us and we all had tea and chocolate biscuits. Colin is a big man with a bushy beard and looks like a Vietnam vet. At first he was quiet and shy and found it hard to talk about his crime and his own appalling injuries.

Harry had told me about Colin but I wasn’t prepared for what I found. Colin seemed such a sad, lonely figure, his eyes full of regret and despair. He’s a paraplegic, paralysed from the chest down. Until then, I didn’t know there were any disabled people in prison but there are, and Colin Richards is one of them.

Having had some experience with disabled people, I am aware of many of the difficulties that they face every day of their lives but Colin’s difficulties are tenfold. He confided many things on our visits but one of the most poignant was just horrible.

He explained to me that one of the worst things about being a paraplegic, other than not being able to walk, was the difficulty of not being able to go to the toilet. Instead, he has to evacuate his bowels by hand. When he wants to go for a pee, he has to insert a small plastic tube down his penis – a terrible thing to have to do by anyone’s standards. For Colin, this unenviable task was made much worse.

While he was in Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight, the rubber gloves and plastic tubes that Colin needed were denied to him. He was told that he was only allowed five a week, while he needs five a day! When he asked why, he was told: ‘We will not give you any more plastic tubes in case you hang yourself with them!’ Colin pleaded with the authorities and tried to explain that he really did need the tubes and rubber gloves. In the end the authorities gave in and said that he could have ‘new for old’. Colin must hand in his used tubes and gloves and then he can be issued with new ones.

Colin’s cell was 12 feet by 7 feet, just big enough for his wheelchair. He is not able to turn his wheelchair around nor move it about. There are no handrails fitted in the cell but every day Colin is expected to drag himself in and out of bed.

The communal TV room is situated on the top landing, which makes it impossible for Colin ever to watch TV. All he has to take away the boredom is his small radio. At one time, a friendly inmate would carry Colin on his back up the iron steps to the TV room but the screws stopped this. They said that it couldn’t be allowed in case the inmate dropped Colin, because the prison authorities were not insured for such an accident.

That goes for the screws too. They are not supposed to lift Colin in case they injure their backs. That’s fair enough; Colin is a big man and very heavy and the screws shouldn’t have to risk injury by pulling him in and out of his wheelchair. But Colin needs help. If the inmates aren’t allowed to help, and the screws can’t or won’t help, who the hell will?

On one of my visits to Colin, he told me that the National Health Service does not apply to prisoners. While you’re in prison, your health care is the responsibility of the Health Care Service. Prisons are allocated a sum of money for health care each year. When the money runs out, so does the dental and medical care.

When they first go into prison, all prisoners undergo a medical examination in the reception. Medical records only follow you into prison if the medical officer decides that there is a good reason for having them sent. Unless you tell the medical officer of any health problems you have, he won’t know about your ailments, so you may not get any treatment for them. In general, he will ask you if you have been receiving any medical or psychiatric treatment, if you have had any problems with alcohol or drugs and also whether you have HIV (the AIDS virus) or if you have had contact with anyone with HIV.

The physical side of Colin Richards’s problems is obvious but the mental problems he is suffering run much deeper. I feel very strongly about Colin’s situation. The crime that he committed was an appalling one, as you will find out when you read his chapter. However, the medieval days of throwing a prisoner into a dungeon and letting him rot are long gone. As a civilised nation, we would be appalled if an animal was being treated in this way. Colin Richards is a human being and should be entitled to human dignity. He has nobody. Soon after he was sentenced his wife left him and now lives in France with the two children he adores. Since he’s been away, both of his parents have died. He has nobody to care for him nor to help him; every day of his life is a struggle.

He told me about a visit that he had recently. His visitor had travelled a long way for the two-hour visit. It had taken Colin all morning to get ready and there were only three-quarters of an hour left of the visit but still nobody had come to help him across to the visiting hall where his visitor was waiting. By the time he finally reached the five steep steps leading into the hall, he had had enough. Still, no one came to help him. The hall was packed with cons and their visitors. Nobody looked up or gave him a second glance.

‘It felt like I was invisible,’ he said. ‘The door behind me was locked. I couldn’t go back and I couldn’t go down the steps. I just sat there unable to move. In sheer desperation, I cried out: “Please, somebody help me!”

‘The whole of the visiting hall fell silent. Tears rolled down my face. I was helpless. I just sat at the top of those steps and cried. At that moment I just wished I was dead!’ His eyes filled with tears as he spoke and he dropped his head.

I didn’t know what to say to him. Normally I am never stuck for words but, for the first time in my life, I struggled to find the right words to say, to give him some kind of hope.

‘There must be something someone can do.’ I told him.

He looked at me and sighed: ‘Oh yeah, what?’

As I left the prison that wet afternoon, I promised that I would find out what could be done to help him. All the way home on the train, I couldn’t get Colin out of my mind. There had to be some kind of help available, but what? I didn’t know where to start.

When I got home I looked up a booklet written by the Howard League for Penal Reform. There, they list all the organisations that are useful to people in prison. As I thumbed through the pages, I found that there were groups and counselling services to help just about everyone – there is a Rastafarian Advisory service, a Gay Rights action group – in all, over 66 different organisations. To my surprise, there was nothing for disabled people in prison. In the ten years that Colin has been in prison, he has never had any counselling to help him to come to terms with his disability. Surely, I thought, in the new prisons that are being built in this country, they can build some kind of secure unit with facilities to cater for the likes of Colin Richards.

I promised Colin that I would try to help him – not to campaign for his release but to make the public aware of what was happening, and continues to happen, to people like him.

Most of us are unaware that there are people with disabilities in prison, just as most people think there is only one women’s prison in Britain – Holloway in London. In fact, there are 12 in England and Wales. Holloway Prison provides a national centre for treating women with psychiatric problems. Styal Prison, which is in Cheshire, Cookham Wood in Kent and Bullwood Hall in Essex are all closed prisons for convicted and sentenced women prisoners. The only other closed prison for women is H Wing at Durham and that is where I visited most of the women in this book.

Durham H Wing is a small unit inside Durham men’s prison. The self-contained unit holds up to 40 women, all serving long sentences, and most are classified Cat. A. Women are allowed to wear their own clothes as long as they’re considered to be suitable. However, there are many other things that have to be taken into account when you’re a female prisoner. If you’re pregnant and likely to give birth shortly after your arrest or committal, you will go to one of the three mother and baby units that exist at Holloway, Styal and Askham Grange.

According to prison rules, pregnant women prisoners should not be alone at night; they must share a cell or have a bed in the hospital wing so that there are other people around to call on for help if necessary. If you give birth while you are in prison, or if you have a very young baby when you are sent to prison, you can apply to have your baby with you. The mother and baby unit at Holloway takes babies up to nine months. At Styal closed prison and Askham Grange open prison, the age limit is 18 months.

If you apply to keep your baby with you in prison, your application will be considered very carefully by a team of doctors, health visitors, paediatricians, prison staff and Social Services. They will consider different factors:

a) if your other children were in care before you were sent to prison;

b) whether your baby will be over the unit age limit before your release;

c) if you’re suffering from a mental or physical illness that will affect your ability to look after your baby;

d) if you are considered a disruptive influence and will not co-operate with staff.

Once you have been accepted into the unit there are, of course, strict rules and they must be followed.

The way each unit is run varies but there are rules about not having your baby in your bed and about when you’re allowed to bath a baby. Babies are usually left in a nursery for at least four hours a day while the prisoner is at work or in a class.

Depending on your behaviour, the Prison Service can decide to move you to another prison. This could mean heartbreaking separation for you and your baby. If, for instance, you are at Askham Grange and your baby is 12 months old and you were then sent to Holloway, your baby would be over the unit age limit and the baby would have to go somewhere else. There are special visiting arrangements for children who are not in prison with their mothers. They can be brought in for fortnightly visits. These visits are extended and much more relaxed than other visits but the prisoners find it difficult and become frustrated.

The overwhelming need to mother their children can sometimes be the cause of trouble inside women’s prisons. Linda Calvey, who I met in Durham H wing, told me: ‘It really gets to the women, being separated from their kids. It wasn’t so bad for me because mine were a bit older. But not being there for them if they have a problem; knowing someone else is looking after your kids, is the worst. You feel helpless!’

When I met Linda, she hadn’t long become a grandmother and she proudly showed me photographs of her grand-daughter. Prison is not the sort of place you expect to find a grandma and Linda Calvey certainly doesn’t look anything like one. When I visited her, she looked young, was dressed in trendy clothes and was planning to remarry.

Over 80,000 offences against prison discipline are punished by the authorities each year. A high level of these tend to be in young offender institutions and women’s prisons.

Many of the long-term prisoners to whom I have spoken tell me that the thing that gets under their skin most is the stupid rules in prison. These rules often don’t make any sense to the prisoner and they find themselves getting in trouble for what seems to them just a screw having ‘an attitude’. Take, for instance, the rules about shaving. Men are expected to shave daily, unless they already had a beard when they were arrested. If you want to grow a beard or a moustache or to shave one off, you have to make out an application to the governor. While this may seem a stupid rule to the prisoner, when I asked a prison officer the reason for it he said it was simple: ‘In case the prisoner escapes! Every year prisoners have an up-to-date photo taken of them, to be issued to the police if they were to escape. If they had grown a beard inside prison then nobody would recognise them.’

Prison discipline is a big part of prison life. If a prisoner commits an offence while in prison, the first thing that happens is that he or she is put on report. The forms are handed to the governor and the prisoner will have to report to him. If he is found guilty of the offence, then the governor can hand out a variety of punishments:

a) a caution;

b) loss of privileges for up to 28 days (14 for prisoners under 21);

c) stoppage of up to 28 days’ earnings (14 for prisoners under 21);

d) confinement for up to three days;

e) up to an additional 28 days in custody;

f) exclusion from work for up to 14 days;

If these punishments are not considered to have worked, there are other control measures, like confiscation of property and Rule 43.

Rule 43 means that you are kept in solitary confinement, separated from the main wing of the prison, and have a different regime from other prisoners. There are two types of Rule 43 prisoners. The system is sometimes used to give a violent man a ‘cooling off’ period, generally known as GOAD (good order and discipline), or is sometimes used for a prisoner who could be a target for physical attacks, such as a child killer.

Alternatively, a prisoner could be transferred to another prison under the order of GOAD. Once all of these measures have been tried and have failed, and if the prisoner is violent, the governor can order that he is:

a) temporarily confined in a special, unfurnished cell called ‘special accommodation’;

b) placed in a mechanical restraint, i.e.:

– a body belt (with iron cuffs for male prisoners and leather cuffs for female prisoners);

– handcuffs (male prisoners);

– leather wrist straps (female prisoners).

These tough measures are only used if the governor feels they are necessary to prevent the prisoner from injuring himself or others. If a prisoner being moved from one part of the prison to another kicks out, ankle straps can also be used to restrain him.

If the medical officer thinks the prisoner poses a danger to himself or to staff, he can order him to be held in a protective cell or placed in a loose, canvas restraint jacket (straight jacket).

Prisoners quickly become versed in all these rules and punishments and few behave so badly that they have to be used. Lifers, especially, learn to ‘play the system’, as they call it. Many I met were involved in disputes with the prison authorities over what they see as their rights. In fact, I think some prisoners probably know more about the law and prison rules than the Home Secretary does! I’m sure, too, that fighting the system is one of the things that keep many prisoners going. Few are better at playing the system than Jim Dowsett who tells his story in this book.

Jim is forever fighting for his rights. When I met him he was busy suing a prison officer after a row and also writing to the Crown Prosecution Service to order the Suffolk police to return all the paperwork they took from his office after his arrest. Jim was serving his sentence in Whitmoor High Security Prison in March, Cambridgeshire. I met him through a friend, Joey Pyle, who was serving time in the same prison. Joey gets on well with Jim because they’re both businessmen, so I suppose they speak the same language.

Jim duly rang me and I promised to visit. I asked him if there was anything he’d like me to bring up for him and he said, ‘Saucepans’. Apparently the prison was allowing Joey and Jim to cook some of their own meals. So I popped into Woolworth’s on the way and bought three non-stick pans.

As prisons go, Whitmoor is better than most because it’s modern. Security is very tight. You are thoroughly searched as you go in, checked with metal detectors and there are plenty of security cameras around. However, the visiting hall is carpeted and, instead of the usual school chairs and Formica-topped tables, there are low easy chairs and coffee tables. There is even a play area in the corner so that the prisoners can get to see their children.

The hall is vast, like a big aeroplane hanger. Mainstream prisoners sit on one side and the ‘nonces and ponces’ (rapists and child molesters) on the other, separated by a gangway and prison officers. This is the only time that the two groups of criminals get close to each other.

At the back of the hall, separated by a wall, are the Cat. A high-risk prisoners.

I’d seen photos of Jim in newspaper cuttings but when I met him, he looked much older than his 48 years. That’s what prison does to some people – it ages them inside and out.

Avril Gregory was 20 years old when I first visited her. She is beautiful, just like a china doll. She looks naive and sort of lost. When she talks, there’s none of the usual enthusiasm of youth. She speaks dully. I met Avril through Linda Calvey in the H Wing at Durham Prison. I asked her if she wanted to be a chapter in my book and she said she would have to ask her mum. A few days later a letter arrived saying her mum said it was all right. Unlike a lot of prisoners, Avril was glad to tell me her story and was completely honest. She never once tried to evade any questions nor to bend the truth. She told me exactly how it was. While I was writing her story, I felt sad that such a young girl could end up serving life. Parts of her story made me cry. But when she told me that she went looking for the boy who was killed with two knives, a pickaxe handle and a cosh, I couldn’t believe my ears.

Avril told me:

I know what happened was terrible and I know I had to go to prison. I expected to be punished. But I didn’t kill Scott Beaumont. I was just there at the time it happened.

When we all went out on that Friday night, never for one moment did we ever intend for anyone to be killed. We were just kids and when you’re young you’re just stupid. You just don’t think of the consequences of what you’re doing. That’s why I wanted to tell my story – so if there is a young tearaway reading this, they might stop and think before they do anything stupid. Before it’s too late. It’s too late for me – I’ve ruined my life. I know I will always be known as a murderer and a lifer…

A new scheme has been set up to help constantly reoffending youngsters in Nottingham, some as young as 15. The court sends them in groups into Nottingham Prison. There, lifers such as Harry Roberts take them on a tour around the prison and show them what prison is really like. The youngsters are handcuffed and locked in a cell. Then lifers talk to the kids at street level, telling them that it’s not ‘big’ to be in prison, that it doesn’t matter what anyone tells them – it’s shit being inside.

Recently, I went to visit Harry Roberts in Nottingham Prison. He told me that the day before he had been showing a group of youngsters around. He said:

We were walking across the exercise yard, chatting to the kids, showing them around. One of them had just expressed his greatest fear of prison, asking if it was true that boys are raped in jail. Just at that moment a big black man called out:

‘’Ere, Harry, save one of those for me!’

The big fella was only larking about but it scared the boys half to death – they couldn’t have been any older than 15. When they left the prison, one of the boys came up to me and said that he is never going to get in trouble again, because he never wants to go to prison.

The longest-serving prisoner in Britain is the triple child-killer John Straffen. It was in 1951 that the name Straffen first caused nationwide revulsion. He was sent to Broadmoor for strangling six-year-old Brenda Goddard and her friend Cicely Batstone, aged nine, near Bath.

Seven months later he escaped from Broadmoor. After just four hours of freedom, he strangled his third victim, five-year-old Linda Bowyer. This time he was sentenced to death but reprieved from the gallows just five days before his execution date. The sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. Doctors declared that he had a mental age of nine. At his trial the judge said: ‘You might just as well try a babe in arms.’

He’s been in prison ever since and is currently in Long Lartin Prison in Evesham, Worcestershire. Over 43 years of incarceration have done nothing to rid John Straffen of the terrible burden he carries with him of his shocking crimes. His eyes are narrowed and blank. Twice he has been turned down for parole and it is doubtful whether he will ever be released. He is a lonely figure just waiting to die.

Many of the people I’ve met while writing this book, like Colin Richards and Avril Gregory, have been sad and, after meeting them, you feel very low – their sadness is contagious. I think the Nottingham scheme for youngsters is a great idea. Let them see sad figures like John Straffen so that they can decide for themselves that they’ll never end up like that. Let them see the cells. After visiting so many prisons while researching for this book I can tell you that what I’ve seen has convinced me to stay forever on the straight and narrow.

The worst place I visited was Rampton, when I went to see Richard Dennick. Rampton Hospital is a deceiving place. On the outside it has the look of a military barracks but, once inside, it has the coldness of a Victorian asylum. The long corridors seem to wind for miles. It’s like a rabbit warren. On the walls hang paintings done by the inmates, and down each side of the corridors are big, bolted doors, behind which are the patients.

I was taken into the depths of Rampton, to Concord Ward, to see Richard Dennick. The thing that struck me was the cold emptiness of the place. I had visited my husband Ron at Broadmoor but it was nothing like Rampton.

A burly officer unlocked the heavy steel door leading into Concord Ward. As I stepped in, there was a stale smell of confinement.

Every home has its own individual smell but Concord Ward has its own pungent odour, created by 16 men living in a closed environment. The sickening smell is a mixture of stewed tea, tobacco and body odour. The whitewashed walls are stained brownish-yellow from years of cigarette smoke. It looked like a geriatric ward in a general hospital. The big, swinging doors leading into the dorm were open and rows of unmade beds stood on either side. At the end was a room with a small glass window. I peered in. The room was empty apart from a bed; on the door was a big brass lock. It must be where the patients are put if they get ‘upset’.

I was led into a small dining room alongside the kitchen. Under the watchful eye of a screw, Ricky unlocked the fridge to get the milk. I sat down at the table. A small vase of artificial flowers stood on the tea-stained gingham tablecloth. As he started to talk, Ricky poured the piping hot tea. Like young Avril, his voice seemed flat and dull. Not surprising for a 27-year-old man who was given a life sentence at the age of 15.

He has grown from boy to man inside. The crime that Ricky committed was terrible. He killed a vicar in a vicious, brutal attack. In his chapter, Ricky talks openly about the attack and leaves nothing out. After all these years, he still thinks he was right to kill him. He said that, in court, they portrayed the killing as done for pure gain. Ricky explained with anger that they wasn’t interested that the vicar, a pillar of society, had died trying to abuse him. ‘Oh no, they didn’t want to hear about that,’ he said.

I was very struck by how different Rampton is from Broadmoor. I know Broadmoor well from visiting my husband Ronnie and my brother-in-law Charlie Smith who married my sister Maggie.

I had been visiting Ron for a few months when he told me about young Charlie who was on the same ward as Ron, called Somerset Ward. Ron asked me if I had a friend who would visit Charlie. My sister had just left her husband and was staying with me. I said I would ask her. The very next day she made the long trip up to visit Charlie Smith. Little did we know that that visit would lead to marriage.

Charlie was 35 years old. He had never really known anything other than life in an institution of one kind or another. He was even born in a prison. After a traumatic childhood filled with abuse, he killed for the first time at the age of 17, then again in prison, and was sent to Broadmoor indefinitely.

Eighteen years later he met Maggie and things changed for him. He went out on shopping trips and on a day visit home – under escort, of course – before applying to be transferred to the Trevor Gibbons unit at Maidstone psychiatric hospital. However, these things take time. For Maggie, as well as Charlie, it will be a long wait.

All the lifers in this book have very different stories to tell. I was very aware when I was writing it that some people think such criminals shouldn’t have the opportunity to tell their stories at all, for fear that they will glamorize their crime and, of course, themselves. These people will say, ‘What about the victims? These murderers may be spending their lives in prison but at least they’re still alive, unlike their victims.’

I do know, or at least I can imagine, that this is hard to take, especially for the families who lost someone they loved through someone else’s act of violence. But we can’t pretend that these people don’t exist. They do. They made the headlines, they were found guilty of murder and, quite rightly, they have been locked up. However, after talking to so many lifers and hearing their stories, I don’t think that murder should carry a mandatory life sentence. I do think that if you commit murder you should go to prison, but I think that each case should be judged on its own merits. Take the case of young Avril. She should have been punished – she admits that – but not with a life sentence.

In her chapter she openly admits taking the knives that killed the boy, but she didn’t kill him. Someone else did. Ricky, too, should be punished for what he did, but doesn’t the fact that the vicar tried to abuse him count for anything? He was a young, impressionable boy who hadn’t even discovered his own sexuality. The 64-year-old vicar was a man of the cloth – a man to look up to. Ricky was confused – and still is.

In a strange twist of fate, these lifers have become victims themselves. I haven’t set out to glamorize them or excuse their crime in any way and I haven’t made heroes of them. They’re not heroes. However, this is probably the first time they’ve told their own stories in their own way and in their own words. If you read their stories, it makes it easier to understand how such terrible things can happen. Surely, that’s no bad thing.