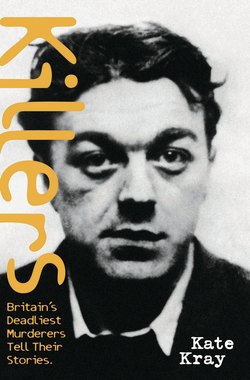

Читать книгу Killers Behind Bars - Kate Kray - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

John Straffen

ОглавлениеIt was a cold, grey November day; the early morning air was freezing. The thin, chilling rain was still falling as I parked my car in the visitor’s bay. I pulled my collar up, ducked my head down against the icy drizzle and walked towards the prison. I had come to Long Lartin high-security jail in Evesham, Worcester, to visit Europe’s longest-serving prisoner – John Thomas Straffen.

It was in 1951 – Winston Churchill was Prime Minister and the scars of the Second World War were still evident – when the name Straffen first caused nationwide revolution. In July of that year, Straffen came across a little girl named Brenda Goddard, aged six, in a field and offered to show her where to find some flowers. It was there that he strangled her.

On 8 August the same year, he strangled Cicely Batstone aged nine.

At Winchester Assizes, doctors declared that Straffen, then aged 21, had a mental age of nine, and was found unfit to stand trial for the double murder and was subsequently sent to Broadmoor Hospital for the Criminally Insane.

Seven months later, he escaped from Broadmoor. He gave the guards the slip, climbed on to a shed and scaled a wall to freedom. After just four hours on the outside, he murdered his third victim, five-year-old Linda Bowyer. Linda was found strangled in a wood near her home at Farley Hill, ten miles from Broadmoor. This time, Straffen was deemed fit to stand trial and was sentenced to death by Mr Justice Cassels, but reprieved from the gallows just five days before his execution by the then Home Secretary, who advised the Queen to exercise her prerogative of mercy.

The sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. The judge at his trial said, ‘You might just as well try a babe in arms.’

Straffen has been imprisoned since 1951 making him the longest-serving ‘lifer’ in Britain and Europe.

As I waited in the visiting centre prior to meeting John Straffen, I thought about his crime and felt somewhat apprehensive and doubtful about visiting a child murderer. I admit that, after reading the newspapers and watching news bulletins about a child being killed, I, too, stand up and shout, ‘Lock ’em up and throw away the key,’ and that’s the last I think about it. But what happens to offenders after they have been sentenced? Capital punishment has been abolished and we no longer live in the Dark Ages when convicted killers were locked in dungeons. Nor do they fall off the face of the earth; they do exist, and burying our heads in the sand doesn’t make them disappear.

In John Straffen’s case, society did just that — locked him up and threw away the key. After more than 49 years in prison, he is still a Category A high-risk prisoner and for such prisoners security is tight, even tighter than when I visited my husband Ronnie Kray in Broadmoor.

I felt like I was visiting Hannibal Lecter in the film Silence of the Lambs because I was a woman visiting a dangerous man whom no one had seen or heard of for nearly 50 years. The names of Brady and Hindley are synonymous with child-killers, but the name of Straffen is clouded in a cloak of secrecy.

I handed my VO to the officer. I was told to leave my handbag in a locker; I was not allowed to take in even the simplest of things, such as a pen and paper. The only money I was allowed was a handful of loose change for the coffee machine in the visiting hall. An image of my face was digitally printed on to a security badge. My hand was placed on to store the identifying characteristics of my palm and fingers, and then I was asked to remove my jacket which was put through an X-ray machine.

I walked through a metal detector and was ushered into a small side room and bodily searched, top to toe, by a female officer. I was moved on to several more check points, where on each occasion my handprint was checked and double-checked. Eventually, I went through a turnstile similar to one at a football ground, but this was no game, this was for real. For the last time, my hand was checked and I was told to sit at table number 12. The visitor’s area resembled a school assembly hall which had a stage built at one end with five officers sitting behind a blue guard rail. At the other end of the hall was the control unit manned by one officer, guarded by at least eight others.

I looked around; across the ceiling were blue wrought-iron girders with swivelling security cameras monitoring every move. The only indication that they were active was a small, red flashing light. For a moment, I gazed at one camera wondering who might be watching me, but quickly I averted my eyes. Lined regimentally across the hall were approximately 40 low tables, all numbered, surrounded by four chairs that had been screwed to the floor, three beige in colour and one brown.

I sat down in the brown seat at table number 12 only to be told by a burly officer that the brown chair was designated for the inmate only, and that under no circumstances was I allowed to touch the prisoner.

I didn’t know what to expect as I waited to meet the man who had spent almost half a century behind bars. I wondered how I would greet him. I didn’t want to seem over-friendly or too aloof but, on the other hand, I was the first person he had agreed to be interviewed by.

My thoughts were broken by the activity in the control unit, and suddenly officers were on alert indicating Straffen’s arrival. A loud electronic buzzer sounded, an iron door opened, an officer nodded to the control unit and warned, ‘Cat-A man coming through.’

John Straffen’s 6ft 2in stooped frame appeared in the doorway. He was wearing the prison-issue blue-striped shirt, denim jeans and jacket. Gone was the mop of blond hair which gave the killer a respectable look of innocence way back in 1951. Instead, he was completely bald but had hair sprouting from his ears and nose giving him a sinister appearance. He did, indeed, resemble Hannibal Lecter. I stood up, smiled and, with an outstretched hand, said, ‘Pleased to meet you, John.’

His cold, bony hand gripped mine. His eyes gazed unblinkingly. A shiver went down my spine. He sat down in the brown chair and seemed shy and awkward. I asked if he was OK, sat beside him and looked into his haggard face; it was etched with pain, or was it sadness? His eyes struck me first, his piercing blue eyes, like the innocent eyes of a child trapped inside an old man.

I studied him carefully as he began to speak. He whispered politely in a West Country accent that he would like a drink and a piece of cherry cake – if I didn’t mind.

I went to the WRVS canteen and returned with four wrapped Genoa cherry cake slices and two plastic cups of tea. I started chatting to him about this book, when he suddenly interrupted me. ‘No wipes,’ he said. He meant napkins. He wanted napkins. It was almost as though he wanted normality. I went to the counter and found some. I continued to tell him about the book. Again, he interrupted. ‘I can’t open my cake,’ he said as he handed me the small wrap.

He was like a child. An innocent child, one who couldn’t even manage the plastic of a piece of cherry cake. Looking at John Straffen, it was almost impossible to believe that, for no rhyme or reason, he had killed three children. He had had no motive for the crimes, none whatsoever, and certainly no sexual motive. There was one word that had been nagging away at me – why?

This was the first interview John Straffen had given and, as his story started to unfold, I thought about the little girls who were still in pig-tails when they tragically lost their lives. Those precious children never experienced any life at all, they never grew into teenagers, or were able to marry and have children of their own, and I felt saddened. But I had to take a step back and suppress my gut instinct to condemn him. I just listened to what he had to say. Whether I liked him or not wasn’t important; I wasn’t there to judge him, he had already been judged way back in 1951. This is what John Straffen told me…

I didn’t understand why the judge put the black cloth on his head, he just looked funny. He said they were going to hang me. I heard what the judge said but I didn’t understand what he meant.

My mum started to cry, and shouted out in the court that I didn’t do it. But they didn’t listen; instead a policeman took her away. I wanted to see her to tell her not to cry, but they wouldn’t let me.

I was taken to Wandsworth Prison in London and put on E Wing. There were only three cells on that wing, they were known as the ‘death-watch cells’, like the death-watch beetle, I suppose. These were the only cells in the prison to have two doors, one to enter and one to leave by. If you left by that door you never came back as it led directly to the gallows.

I was on 24-hour suicide watch. That was silly; I didn’t need to kill myself, they were going to do it for me. The cell was painted battleship grey and was freezing cold, with a bed, a table and two chairs. I was guarded by six officers on a rota, morning, noon and night; they never left my side for a moment, not even when I went to the toilet. I would sit on the bed all day watching the officers play cards. None of them spoke to me, except one officer, Mr Honey. He would bring me in little treats now and then and sometimes have a friendly word for me.

At night, I used to hear them testing the trap on the gallows to make sure it worked OK. I suppose that’s the reason they weighed me to make sure the sandbags were accurate for a clean execution. I wasn’t scared, I just went to sleep.

When they told me they had changed their mind about hanging me, I was moved from the death-watch cells to another prison. On one hand I was glad because I would be able to see my mum, but on the other I wasn’t, because I was put into the mainstream prison where the other prisoners used to hit me. In the early days, I was beaten up on a daily basis; never a month went past when I didn’t have a black eye or a fat lip.

I don’t get hit quite so much nowadays. At first, everybody knew who I was and wanted to hurt me, but I’ve seen so many people come and go, now nobody knows who I am, I’ve just been forgotten.

The last time I saw my mum was in the late Seventies. She had come to visit me in Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight. The long journey from Bath to Parkhurst proved too much for my mum, she started saying peculiar things on the visit, things I didn’t understand. I think she was going mad. The screws had to take her out of the visiting hall; I never saw her again. She died in March 1982. I wasn’t told until 12 days later; by then she had already been buried.

I wish I had seen my mum just once more before she died, to tell her I loved her, and that I was sorry. I would have liked to attend my mum’s funeral, but it was too late. My brother Roy and sister Jean used to visit me but they stopped. I’m not sure of the reason why, but I can’t blame them really.

I spend most of my time locked in my cell. I can’t get used to the new central heating system, it’s too hot, I’ve got no control over it, I can’t even open a window. The heating system is the only way to judge whether it’s hot or cold outside. You see, when you are in prison there are no seasons, it doesn’t matter if it’s winter or summer, raining or snowing, or even if it’s day or night. Your cell becomes your world and the only escape is reading. I like detective books, they’re my favourite, but two months ago I thought I was going blind. I was a bit scared, but I had a cataract operation and now I can read better, and no longer need my glasses.

At the moment, my only contact with the outside world are paid prison visitors, but next month I will get my own television set in my cell, then I will be able to watch the wildlife programmes and the cartoons I like — in peace.

Every year I’m automatically considered for parole, but every year I’m turned down. Since 1951, the authorities have used three excuses, which are: I am a danger to the public; a danger to women; and a danger to children. This year, I was turned down for parole without seeing anyone, no interview, nothing. The excuse given — a danger to children. It’s just not fair.

I admit I killed the two little girls in 1951 but I said at the time, and I will say it again now, that I did not kill the little girl who was found in Farley Woods. I have no reason to lie, and have nothing to gain.

I think it’s time I was released. Although I’m 68 years old, I could still get a job in a factory near the prison. I could tie up bundles of books maybe and earn £5 a week. I’d like that.

There are lots of things I would like to have done but have never been able to. I have never driven a car, or been in an airplane. Never had a girlfriend, never paddled in the sea, stood in the rain or under the stars.

I don’t think I am a danger to anyone any more. I’m an old man now. I’m glad they didn’t hang me in 1951 but I do believe in capital punishment. Some crimes warrant a life for a life. There are some bad men around nowadays, like paedophiles and sex maniacs; hang ’em, that’s what I say, or lock ’em up and throw away the key.