Читать книгу Letter To An Unknown Soldier: A New Kind of War Memorial - Kate Pullinger - Страница 7

Introduction

ОглавлениеOur inspiration couldn’t have been simpler.

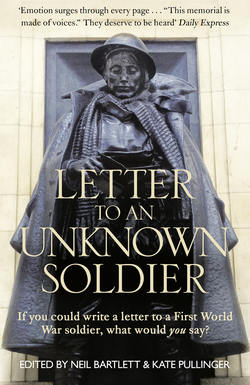

On Platform One of Paddington Station in London a famous First World War memorial by Charles Sargeant Jagger features a life-size bronze statue of an unknown soldier in full trench uniform. He is reading a letter; no one knows who his letter is from, or what message it contains. In the weeks leading up to the hundredth anniversary of Britain joining the war – in a year crowded with official remembrance and ceremony – we invited everyone in the country to pause, take a moment or two, and write that letter.

People responded in their thousands. Some wrote physical letters and posted them to the soldier at Paddington Station; the vast majority posted their letters online to a specially created website. In the thirty-seven days between the 28th of June 2014 (the centenary of the Sarajevo assassinations) and the 4th of August (the centenary of the declaration of war), the soldier received over twenty-one thousand letters. They came from across the country and around the world, and from everyone; from railway workers, writers, schoolchildren, serving soldiers, prisoners, nurses, pensioners – and the British Prime Minister.

The inspiration behind the project may have been simple, but as you will see as soon as you start to read the letters that we have chosen from those thousands for this anthology, people found responding to our invitation far from straightforward. The obvious question of ‘What shall I say?’ quickly splintered into many more. How can I write if I am not a writer? How can I talk about something as big as war? How should I address a dead person? Do I have to travel back in time and imagine I am writing my letter in 1914, or should I write from now? Am I writing to one man – to a particular named individual from my own family history perhaps – or to all the army of the dead? Is the soldier white, or is he black? Is he British, or Canadian, or Indian, or from the Isle of Lewis? And so on … The beauty of the idea turned out to be that the archetypal and archaic literary form of a letter entitled people to answer these and many other questions in their own utterly individual ways. A letter is not a text message nor a ‘like’ on Facebook – in order to write one you have to stop, and think, and feel, and compose not just your letter but yourself. A letter is also not an essay nor a short story. A letter is a page or two long, with a beginning and an end. A letter is private. A letter is everyday. A letter is familiar. A letter is, above all, personal.

All of the letters that the soldier received during the thirty-seven days that the website was open for submissions were published without censorship or alteration or editing. In creating this anthology, we have resisted any temptation to organise our chosen letters by theme or place of origin. A bewildering diversity of voice and form was as characteristic of the soldier’s daily postbag as the frequent reiteration of often familiar tropes, images, phrases and sentiments. That’s why you’ll find the letters we’ve selected in no obvious order, with a politician’s letter next to a schoolchild’s, a queer love-letter next to a military salute, a soldier’s wife next to a pacifist pensioner.

Letter to an Unknown Soldier was commissioned by 14-18 NOW as part of its five-year cultural programme responding to the centenary of the First World War. The entire archive of letters will remain on the current website until 2018, which means that if you want to read more of them all you have to do is go to www.1418now.org.uk/letter/ and start reading. After 2018, the website – including all 21,439 of the letters – will remain part of the UK Web Archive, provided by the British Library. There it will remain permanently accessible, providing future readers with a vivid snapshot of what people across this country and across the world were thinking and feeling in the weeks leading up to the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War. They give us a glimpse of what it means to remember a war that is no longer within lived experience; what it means to remember what cannot in fact be remembered.

Remembrance is usually conducted in silence. This memorial is made of voices – numerous, various, contradictory, heart-broken, angry, sentimental and true.

Neil Bartlett and Kate Pullinger,

November 2014