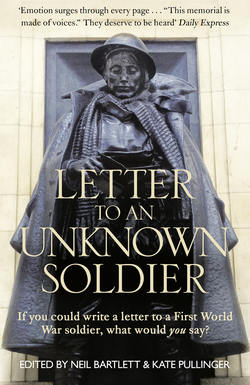

Читать книгу Letter To An Unknown Soldier: A New Kind of War Memorial - Kate Pullinger - Страница 8

Letters to an Unknown Soldier

ОглавлениеDear Unknown Soldier

Imagine you could read my letter now and see how far the world has come since you were fighting in the war. You may have been Unknown then but not now because you have millions of people writing you letters in which most of them are expressing their feelings for you and saying how much of a good person you are.

If I could meet you now there would be so many questions I would ask you but for now here are just 3.

1. What was your family like?

2. What did you like to do?

3. Who were you fighting for?

Shane Cook

14, London, Holloway School

Dear Owen

Your mother called today, I wish I’d been out.

Anyway I made her welcome.

She sat in your chair, I don’t know if she was trying to make a point.

You were very quick off the mark to sign up with your pals.

Not a thought for me or the kids.

Why didn’t you take all the clothes I’d laid out for you?

You’ve only got one pair of smart trousers.

The heavy thick coat is still where you left it.

Your mother said you’ll catch your death, what do I care?

And you’ve left the back gate off its hinge, well I’m not going to fix it.

Anyway I will send you the back pages of this week’s Gazette Times.

Mind you by the time you get it the runners and riders have already run.

I saw the postman again today, I hung out the washing, as all the women do, we all watched him pass, then we all went back inside.

God Bless.

Mary

Mary Moran

Sheffield

You don’t know me yet, but I have things to tell you. You’re about to go back, and I’m sorry to say it’s going to be worse than ever this time. You’re going to be wounded, I’m afraid. Very badly. But you’ll survive. You’ll make it home. You have to, you see. Forty years from now you’ll become my grandfather.

Not that home will be a bed of roses. Wages will be down, and three men will fight for every job. At times you’ll be cold, and at times you’ll be hungry. And if you say anything, they’ll come at you with truncheons.

And then it will get worse. There are some lean years coming. And I’m sorry, but along the way you’ll realise: the war didn’t end. It was just a lull. You’ll have to do it all again. This time your son will have to go, not you. You don’t know him yet, but you will. But don’t worry. He’ll get back too. He has to. You’re my grandfather, remember?

And I’ll be born in a different world. There will be jobs for everyone. They’ll be building houses. You’ll go to the doctor whenever you want. I’ll go to school. I’ll get free orange juice. You’ll get free walking sticks. But most of all we’ll get peace. Finally, year after year. I will never go to war, you know. I will never have to. The first time I go to France will be a trip with my school.

So go back now, and play your tiny part in the great drama, and sustain yourself by knowing: it comes out well in the end. I promise.

Lee Child

Writer

Dear Soldier

You are strong and brave. You are going to face unknown terrors because you have been told that you are protecting your home and family by fighting the threat of domination and oppression by a foreign foe.

Your finest emotions of loyalty and courage have been subverted by power-hungry empire builders, both politicians and monarchs.

The same lie has been perpetrated in France, Germany, Austria-Hungary and Russia, and will be spread across the globe.

Consequently brave young men across the world have been led to believe that they are doing the right thing by killing one another.

If you could see into the future you would know that this will happen time and again. Young men, and some women too, will be manipulated by those in power to commit murder for the sake of King and Country/the Fatherland/the Revolution, or for Jihad.

You don’t have any quarrel with those young men who speak different languages and have different religious beliefs.

I am asking you to be even more brave.

TURN BACK.

GO HOME.

Show that you can see through the propaganda and that you are not prepared to kill or die for the greed and selfishness of the ruling class.

Meantime, I wish you well and hope that you return safely, and don’t come back like my grandfather, whose mental and physical health were ruined after nearly four years at the front.

With love,

Anna Sandham

Anna Sandham

70, Oxford, Grandmother

The letter I didn’t send

Dearest Luke

As I watched you walk away with all the other men, marching off to France, I thought I would die from pain. I wanted to wrench you out of that line, take you home to where you belong and know that you would always be safe, and always be you.

This fighting is not for you. You have never been a violent person, you are the most kind and gentle man I have ever known and this will do violence to your soul. I am so afraid that you will come home with nothing behind your eyes but horror and a heart so bounded by stone and afraid of the worst that can happen to people. You would never let yourself love anyone again, through fear of the horror.

I think I fear the damage to your soul as much as I fear you dying. How terrible it would be to live the rest of your life with nightmares, screaming terror and despair.

May God be with you always,

Mum xxxx

The letter I did send

Dearest Son

How proud I was of you as you marched off to defend our country from the Germans, and how wonderful you looked in your uniform. We are all thinking of you, my dearest son, and of the adventures you will have in France. Maybe you will learn a little of the language and eat some wonderful food.

You will be in my thoughts and prayers every minute of every day, my darling boy. Stay well and come home safe to us.

I love you and may God bless you always,

Mum xxx

Sue Oxley

64, Glastonbury, Mother

For my father, who did fight in a war and who came home damaged in his soul.

There you stand, a monument to so many who never returned. Did you leave home whistling, upbeat and expecting adventure? Were you there at the outset, when people still believed the war was just and would be over in weeks, or months at most? How quickly did you realise you had been sold a lie? I look at you and wonder who you knew – did you serve with pals from home, all in together and watching out for each other, or did you join up far away from those who knew you, because you had something to hide? Did you by chance meet a boy called Cyril from Cornwall, who would have claimed to be eighteen, but who was just a child of sixteen? Did you, like him, leave the safety of your hometown to sign up in London, away from the friendly local recruiters, who knew your age and sent you home to your mother? How many were there like him in your unit? How many of them made it home, like he did? How many went on to have children, like Cyril’s daughter, my mother?

You can’t tell me, of course, but let me tell you something. We still recruit children today, but we do it openly, seemingly without shame. We have learned nothing from your suffering and sacrifice; recruitment remains a numbers game. Children sign up more willingly, they ask fewer questions, and they get paid less. The ones who join up at sixteen these days often don’t have many life chances. They are too young to vote, but apparently old enough to serve. My grandfather Cyril was just a boy when he ran away to fight. What an indictment it is on our society that, one hundred years after he joined up, we have not progressed enough to apply the simple maxim ‘Children, Not Soldiers’ to our own Armed Forces. I’m glad you can’t understand, because I believe that if you knew how little has changed, then you, like me, would feel ashamed.

Demelza Hauser

45, St Albans, Mother

I sit on the Board of a charity which works to prevent the recruitment of children into armed forces across the world. My grandfather’s story of running away from home in Cornwall at sixteen to join up in London is part of our family history. He died when I was very young, so I never had a chance to ask him about his experiences in the war. It makes me sad that a hundred years after my grandfather was a child soldier, we still recruit children into the Army.

Somewhere in the world somebody is walking on the place where you fell. Or maybe they are lying on their back, face turned to the sun, picnicking with beer and sandwiches. Do crops grow on your grave? Cows move slowly across it? Does a farmhand bend to pick up a bullet casing and put it in her pocket? Has the minefield been ploughed over or left fallow? Are homes built there? Is there a town where once there were battlefields? Fields where once a town stood? Across five continents, one hundred years before you were sent into battle, and one hundred years since, and before and after, and before and after again, lying between layers of earth, under sand dunes, rocking upon the seabed, buried beneath rubble, incinerated into dust: the bones of the fallen. Almost anywhere in the world, wherever one of the living stands now, a warrior has fallen.

We have forgotten their names: The Unknown Warriors. I wonder, at night when the station is still, do they appear from all directions? Dressed in uniforms of every kind, camouflage to cotton and followed by others dressed in the clothes of everyday, farmers’ overalls and jeans, business suits, high-heeled shoes, djellabas, rubber flip-flops and leather sandals, shorts, tunics and T-shirts, trainers, sports clothes and sun hats. I wonder if one day there will be another statue standing alongside you, to those people who fell beyond the battlefield, who were queuing for bread when the shells struck, or serving dinner to hotel guests at a poolside restaurant when a grenade was thrown, crossing the street when they were sighted through the crosshairs of a sniper’s rifle, sitting in front of their office computer when the first plane struck, shopping in a mall when armed gunmen burst in, walking to the fields when they trod on a mine, buying fruit in the bazaar when the suicide bomber passed by.

Would you even recognise this new kind of warfare? As you board your train to France and the trenches, did you ever imagine it would come to this? Will there come a time when we will commemorate them, lest we forget: a statue, a tomb for them too, uncounted, countless? The Unknown Civilians.

Aminatta Forna

London, Writer

Stay safe. Get back. Bring as many back with you as you can manage. Nothing else matters.

Sean

25, USA, US Army, Infantry

For Nathan. I’m sorry I wasn’t there, dude. Things might have gone differently.

Hello Tommy

I never knew you, but my Grandfather, Fred, joined up, like you. He’d been a miner and worked at the pithead at Senghenydd – leaving just before 440 died in the explosion on 14 October 1913. He’d left the colliery to go and work in Dundee, where he also joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, before emigrating to New Zealand in 1911.

Three years later, war broke out in Europe and after working as a gold-digger and miner in New Zealand, Fred joined the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZACs) as a field artillery driver. This involved driving a team of horses pulling a gun carriage into the field of battle. A few days after joining up there was an explosion on 12 September 1914, at the Ralph Mine in Huntly, where he had been working, claiming the lives of 43 men. He must have sensed then that he had some form of charmed life.

Fred served at Gallipoli and at the Somme, where he was injured and hospitalised. Like so many others he never spoke of it afterwards. A million soldiers died or were wounded during the Battle of the Somme, and 100,000 died at Gallipoli, so it’s incredible that Fred survived both campaigns, albeit with injuries.

After being evacuated to England on medical grounds, Fred was visited in hospital by Sarah Jones, who was raised by his half-sister after her own mother died. They fell in love and wanted to marry, but Fred was forced to New Zealand before he could be officially discharged by the ANZACs. Before he returned to the UK he worked for the Wellington City fire department.

Fred made it home to Britain safely and married Sarah in 1919. They settled in West Chislehurst, a suburb of south-east London, and had six children, the youngest being my father. Never one to shy away from danger, Fred joined the London Fire Brigade and received a bronze medal in recognition of his ‘long and zealous service’. Fred served during the Blitz of the Second World War and must have faced considerable danger most nights. He suffered a number of shrapnel wounds while fighting fires during the war.

In 1944, Fred was discharged from the fire service due to injuries, but he continued to work in the theatres of London’s West End as a fireman – responsible for lowering and raising the curtain during each performance.

Fred died in 1967 when I was nine and I wish I’d had the opportunity to talk through his life with him. As I write this, Frederick and Sarah’s legacy is six children, 16 grandchildren and 45 great-grandchildren – 67 and counting. History has come full circle now that three of his 2 x great-grandchildren have been born in New Zealand.

So although I never knew you Tommy, I knew one like you and you and all your companions, whether they died or survived are remembered. Thank you.

Barry Rees

Barry Rees

56, Haverfordwest, Grandson

To let Tommy know my Grandfather’s story.

I remember the day you went to war. The cockerel was crowing all day, setting the hens to fuss. I had to calm them, Mam shaking her head, saying we’ll never get them to sit.

I could tell how far down the lane you’d got. I heard you go by Rose’s dogs and then the crows lifted up out of Kings Copse and I thought it was you.

One of Rose’s dogs got loose last week. I could hear shouting from up the lane and then one of his collies tore into our yard and flew straight into Jenny. She squawked when he hit her. All the cluck and loveliness come out of her at once. He looked at me then, just to check I understood the rules, then he grabbed her up and set off across Pike’s Field.

That evening Rose came round with the dog on a short rope and said we should see it killed. He pushed the dog down onto the lane with his boot on its neck and pulled the rope tight until it couldn’t breathe. I could hear Rose grunting as he pulled the rope tighter and the dog started whining through his nose and his eyes fairly popping out. When it was done Rose asked if we wanted the dog’s body. Mam said, no, thanking you, Mr Rose, but we’d be happy to take one of your chickens to replace the one we lost.

I don’t like Rose. I wish he’d taken the King’s Shilling instead of you, and then I got to wondering, if you offered the King his shilling back do you think he’d let you come home sooner?

Martin Daws

Bangor, Poet

Hello Soldier …

Are you coming, going or a little lost? I can’t tell.

You look so sad, are you? I can’t tell.

You look lonely, so lonely, are you? I can’t tell.

You look worn out, exhausted, are you? I can’t tell.

Nothing left or more to give? I can’t tell.

You look scared, bewildered, are you? I can’t tell.

Stiff upper lip or stifling the dread? I can’t tell.

Steadfast and proud or reservedly petrified? I can’t tell.

A true believer, or believer in fate? I can’t tell.

Here’s what I CAN tell you … past, present and future.

‘Whatever it is, you wear it well, you did us proud, my boy, my son, my soldier.’

Love A Stranger xx

Lisa Turrell

43, Solihull, Raisemore, Marketeer

We work alongside two military charities: Veterans at Ease and Desert Rats Memorial Association. Both work tirelessly to support ex-military personnel, recognising the efforts of our unsung heroes, remembering them with pride.

With most of us asking the same questions,

among them: did you receive this letter today

or weeks or even months ago and produce it

now to refresh your memory of what it says;

is it a love letter, a letter from home, or lines

from a friend you are happy to know is alive;

who knitted that scarf untied round your neck,

the only piece of non-regulation kit and a clue;

is that a smile on your face or is it just the way

your mouth curves when it is settled in repose;

is it possible you never in fact received the letter

but composed it and now are reading it through

one last time before dropping it in the postbag;

if so, is it a love letter, a letter from home, or lines

to a friend who will be happy to know you alive;

yes with most of us asking these same questions

we forget to think this might not be a letter at all

but a list of questions you have prepared for us,

among them: what makes it possible to end now

our conjectures and leave perfectly free and easy,

heading into town or out to Oxford and the West,

with it making no difference to anything apparently

whether we notice you watching us or fail to notice.

Andrew Motion

London, Poet

I am the lady in charge of odd parcels, blurry writing, the not-quite-right addresses. I am the investigator, the letter opener, the get-things-running-smoothly woman. I wear a loose uniform and heels that dig in when I walk. I have auburn, curly hair. My mother called me ‘homely’ once. There are seven drawers in my desk, three down the sides and one across the middle. The bottom right is devoted to you.

There is something thrilling about the tearing of envelopes not meant for your hands. A quick scan – and quick it is, I promise you. I don’t want to pry down the words to find addresses, names, ranks, platoons. The clues are threaded together and the letter moves on, or plunges into the bin beside me. Something always feels wrong about binning those, though.

When I found the first letter addressed to ‘the girls at home depot’ I laughed. Of all the people you could write to, you write to us. I read it out loud on a break, you were so flirty then. Charming and witty like a poet, our warrior poet out on the lines. And punctual too, we looked forward to loopy handwriting on a Wednesday morning. Then you began to change.

Our happy bard grew sad. The letters became too painful to read out, so I locked them in my drawer and left them for days. Something was private about your suffering. After a while I stopped opening the letters.

The letters have stopped. I should have realised sooner, I know. It must be cruel of me, this shameless word-reader, to have left your letters lonely for so long. I resolved myself to burning them in secret, freeing my heart of the burden that is you, my dear tommy. But first, I needed to read.

Sneaking out of the workplace was a cause of some terror for me. I am the girl who is punctual, polite, the early-arrival-who-opens-the-windows. I am not the girl who sneaks out the back door, past the ladies smoking ration cigarettes and to the relative safety of a book store.

I think you must have died. How could you do that to me, without sending so much as a name to call you by? No face to match the words, no frame to fill the hole your letters have left me. My tall soldier, small soldier, blond soldier, brunette soldier. My lost soldier, my found soldier, my brave soldier, my letter-composing coward. I know everything about you, yet I know nothing. How can you mourn someone you cannot prove existed or died? Yet I do, I do.

I am the daughter who aches, who pried, who longs. I am the sister who animates you, runs with you, fights with you and buries you. I am the one who laughs, and cries, and curls up into a ball at the thought of you. I am the one who misses you.

Come to home depot, my silent soldier. I’ll be waiting.

Freya Finch Atter

17, Holsworthy, Exeter College Creative Writing Group, Student

I’m assuming I have family that died in the war, but I don’t know any of them by name. My grandad lived through the Second World War, but he was kept at home to farm. So when I started writing the letter I didn’t have any personal link to build on. Instead I wondered ‘What would happen to a letter sent to a false address?’ My ideas stemmed from there, until I found my soldier and his woman from the home depot.

1 July 2014

Dear Sir,

You are one soldier but you stand for millions. For the millions of young British men who have fought to defend our freedoms and for the millions of us left behind who will be forever in debt to the extraordinary service and sacrifice of your generation.

When you left our shores you did so with hope and purpose. Posing proudly in your uniform, you had a sense of mission and perhaps even of adventure. You knew that you were volunteering to help your country fight a just cause. You did so eagerly, with honour and with the expectation that you might well be home by Christmas.

Today as you read this letter you know, better than we can ever imagine, the monumental horror and suffering of this War.

After what you have seen no-one would blame you for asking why. No-one would criticise you for feeling angry, sad or afraid. Barely any family in our country has escaped unaffected. So many friends have been lost; so many loved ones snatched away from us in their prime. You yourself know you will face further grave danger in the weeks and months ahead.

But be in no doubt; however dark this time of War – our world would have been far darker if you had declined the call to act. Without your service, our security, our values, our very way of life would have been lost.

Know too, that from your toil and sacrifice there will in time be a better world. It will not happen immediately. There will be yet more unthinkable horrors along the way. But one hundred years from now your grandchildren and great-grandchildren will enjoy a peace in Europe and a quality of life that is almost unimaginable.

Historians too will trace back some of the world’s greatest advances to your time. From the development of medicine that can heal wounds and sickness to the emancipation of women and the advance of civil rights for ethnic minorities.

Your bravery and selfless determination will never be forgotten. Your name – and the names of your fellow servicemen – will be celebrated on memorials in villages, schools, churches and universities across the land. Plays and poetry will honour you. Painting and monuments will depict you. Ceremonies will be inspired by you. Thousands will write about you, many will even write to you a hundred years from now.

So as you go from here, know that you are in our hearts. Your service will forever be part of our national consciousness. We are humbled by what you have given for us and we will never forget you.

Yours sincerely,

David Cameron

David Cameron

London, Prime Minister

Dear Unknown Soldier

That is what you are – unknown, unknowable. You are a sign, a symbol: a simulacrum in a shadowy world of simulacra.

There is a gap between what you really are and what you represent, a gap between the fire and the wall, where we stand, transfixed by the shadows in front of us.

Please mind the gap

– the gap between writing this letter and taking real action to rid the world of suffering.

Please mind the gap

– the gap between my sofa and the images of Palestinian slaughter on my television.

Please mind the gap

– the gap between this country and others that don’t have commissioned art memorial projects.

Please mind the gap

– the gap between now and then that allows us to remember.

And remembering is important. But I hope, for your sake and the millions like you, that remembering is not all we do.

Yours truly,

An Unknown Soul

Anonymous

West Calder

Dear Soldier,

Standing at your feet, looking up at you, my cousin Susan and I wonder if we ever noticed you before. It’s odd, looking with clear blue, fresh eyes at you, recalling our childish days when we struggled by with our suitcases – her miserable and back to boarding school, me happy and off to endless Cornish seaside holidays. Living our separate lives, blonde-haired, blood-tied.

We and our children are part of the line that you saved through your bravery and care, at a time when so many other lines were broken. Is it possible that it was you, on that day, somewhere in France and in a foreign field, in all that noise and terror (when surely the only thing to do was save your own soul), you found Harry Black? Was it you who dragged him up out of the trench that had so nearly claimed his life? He took one, bought one, his comrades had all copped one. Harry, the last man left alive and for three days, barely so, lay waiting to be taken up the line and home to a life-changing but nonetheless dignified life?

Standing at your feet I resolve to write this letter to you, because you need to understand what you did that day. We are the line that will go on to prove you right. There was a world worth fighting for, a line to walk, a line to make and a line to hold.

Love,

Vikki

Vikki Heywood CBE

Chairman 14-18 NOW

Dear Grandfather,

You met me once, my father said; it was after both Wars, and I was your only grandchild: a babe in arms. Dad said he was afraid to let you see me. Your wife had killed herself the day my Dad was demobbed, though he always suspected you might have murdered her. I think he was afraid you would do something to me, too.

To everyone else, you were a hero – a soldier who came through the Great War without a scratch, an officer and a gentleman. You were pointed out in the street of the small town you came to live, with pride and respect. For King and Country you said, unyielding as your waxed moustache. But to your family, you were the tyrant who took to beating your wife and sons when drunk, and let’s be honest, you were drunk most of the time. Once, my father and his brother ran away but it was cold and they had no money, and after three days of hunger they came back, to more beatings. Your speciality was whipping my Dad, then locking him up in a cupboard, because although he was the younger he was the brave one, the one who tried to defend his mother and brother. You weren’t the sort of hero who respected courage, or who rescued others at Ypres or Passchendaele. One of your medals was for taking out a nest of machine gunners, one by one. You were a killer, a bully, a dead shot, who had found his natural element in war.

All his life, my father suffered from his own anger, and from trying to understand you; he hated violence and injustice because he had experienced so much of yours. Was it shell shock that made you behave as you did, or your own nature? Was it your own upbringing? Dad said you loved the military life, had been bred for it, brought up to it and expected your sons to follow you into the Army when the next War came along. They joined the Navy and the RAF instead. They spent their whole lives trying not to turn into you, Grandfather, and my father never hit us, or our mother, not once, even when rage and booze boiled through his veins like poison. But Dad would always stop himself. That was his own War – not the one in which he was blown up, shipwrecked and made deaf in one ear. It was the War with you, Grandfather.

Did you have any feelings, or did anger and alcohol consume them all? Was it a form of shell shock, to turn your family into the enemy, long after the War was over? I never knew you, and I never knew my grandmother. She was the loveliest woman, gentle and kind, my father said; an innocent. You would have loved her, and she you. He would weep, remembering, right into his own old age, but he never wept for you.

Amanda

Amanda Craig

London, Writer

Our only boy,

I hope this finds you.

I miss you.

We are doing well as can be expected, considering everything.

We miss you.

How long is it now? A month, a year? One hundred years?

I’ve lost track …

I asked your father if he thought there would ever be peace. He said that people have to want peace for there to be peace. I said people need to be able to see peace to want peace. He said people need to feel peace to see peace. You know what our conversations are like …

I felt peace: When we had you. When you were here.

But since you’ve been gone – (one hundred years) – I can’t feel it anymore.

And I fear I won’t again, until you come back. And stay this time.

Your room is still empty.

So I have no peace.

So I am no help at all.

Come back to us.

I want to see peace, again.

Your father sends his love.

And I, mine.

Your only Mum

Stephen Pelton

50, London, Choreographer

Things you do not know:

When you leave, you will leave a child, growing. When night falls on the day you die, your officer will write two letters to two families, yours and his own. He will say to his mother that he has never had to write a letter like that. He has never knowingly lied before. He helped three of his men to bury what was left. He will ask does his mother think, under the circumstances, he did the right thing when he said ‘it was quick’?

Your wife and your mother will weep together in the kitchen, over a pot of tea. Your wife will smile through her tears and say, ‘At least, it was quick.’ Your mother will shake her head and reach for your wife’s hand.

Your child, a girl, will be born early, on a hot June night, to the sound of the first bombs to fall on London from a fixed-wing aircraft. Those bombs will hit the school in Upper North Street, and kill eighteen children, mostly between the ages of four and six years old.

You will be moved with infinite care and laid between men you never knew. Your wife and mother choose the words ‘Only son and beloved husband’ for your headstone. They mean to come and visit your grave when they can save the money. They never do.

Your daughter’s husband will be called up to fight in another war. He will leave her, pregnant with her second child, at home with your wife and mother. He will have reinforced the kitchen table with metal sheeting from the works, and they are used to sleeping underneath on a single mattress from the spare bed. Your eldest grandson, a boy of three, lies awake, listening to bombs falling on the streets. He loses his best friend.

Before their own house is hit, killing your wife and mother, your daughter and son are sent away to a farm in Wales. They never go back.

Your son-in-law will be killed at Cassino. Your daughter will not marry again. She helps out at your grandson’s school, then trains to become a teacher.

Your grandson becomes a teacher too, lecturing in sociology at Cardiff University, and he marries one of his students. They are pacifists. They do not approve of the wearing of red poppies on Remembrance Sunday but when their son, your great-grandson, comes home from his school, aged five, with a poppy, they let him pin it to the wall chart – but only after an argument.

Your great-grandson will find your photograph in a drawer, and will ask who you are. He is the first person to visit your grave, over eighty years after your death. He will become a military historian, and battlefield guide, keeping your memory alive and the memory of all those who fell with you. You don’t know this, but you’d be proud of him.

Vanessa Gebbie

Lewes, Writer

Soldier, acknowledge our salute. I know you will. You’ll slam that foot down, like a dog pissing on a tree, this is your ground; you won’t move. And as you raise that hand with the same conviction upon which you slam it against your enemies, we will know that you are resolute.

But I want to see into your eyes. I want to see if your convictions are betrayed by your thoughts. Because I worry that we have made you a caricature: the depth of a person is marked by the contradictions within them. I worry that it is too easy to portray you as the valiant hero, the resolute patriot, the loving father. There has to be more to you. And though you were equal to your deeds when you did them, I wonder if you could endure this image after. You cannot be defined by your actions, and if these actions are what we remember, then we do not know you.

Soldier, don’t stand for this misrepresentation: leave. Rip through the foundations that hold you down, tear open the tomb that entrenches you. As the material flakes away, we will be reminded of you shaking in the trenches, cold and wet, laden with the burden of self-preservation. But you overcame that burden – how else would you have ended up here?

Overcome another: and as you rise above the material we once thought you were, you give us hope. Because when life kicks me in the teeth, I need to know that I can rise above it. So be the man that meets triumph and disaster and treats them as impostors. Be more than what happened to you; teach us that we are more than what has happened to us. And when our values are strewn into the stream of life, leave us to fish out some new ones.

Soldier, look down. Let us know what you see; because I see the same things differently all the time. And it’s really hard to be grounded when you can’t find the spot you were standing in yesterday. This river keeps flowing and most of our dads never taught us to fish. So show us where to go.

I think you do that. Your statue was never meant to represent one thing, one position, one person. You stand as a springboard for each of us, to our own little spot. That might be to a conversation with an old relative, or an exploration into our own convictions, or an emblem of a broader notion.

Regardless, you stand resolute. Your stance is firm. Your posture is sure.

Your eyes: a mirror into ourselves.

Sean Spain

22, Bath, Bath Spa University, Student

I have been influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of the Overman & by Rudyard Kipling’s poem ‘If –’.

Dear Jack

I know we’re not on speaking terms but I’ve been thinking what if you die.

I’ve been finding it hard to forgive you and it’s worse because I’m the only one who thinks you’ve done anything wrong. Your family and mine certainly don’t.

It was hard to bear the white feathers and specially getting one from Ellen. Don’t flap your hand at me, I know you like her. (So do I of course, but you’re the hero now.) You’ll still say it wasn’t the feathers, you just saw the light.

Maybe you’re right. Maybe it is sometimes not wrong to kill people. Maybe this war is a glorious exception and

No, I can’t think that or only for a short time about four o’ clock in the morning. I hope in a way you’re still as determined as the day you got on the train and don’t have doubts at night to suffer as well as all the other things there. When it’s over we can argue about it in the pub.

I keep wanting to say how could you? how could you leave me? and trying to stop myself.

I want you to regret it bitterly. I’m sorry.

Will I send this? It helps writing it anyway. If I go to prison they might not let me write to you so I will send it. I expect your mother will send socks and chocolate. (Ellen too?) So just this from your friend still

Edward

Caryl Churchill

London, Playwright

Dear Tom

I hope you don’t mind if I call you Tom. But I seem to have got to know you quite well over the years. You see I was a policeman at Paddington Station for a number of years and I walked past you almost on a daily basis and each time I spared you a thought and what a great man you were having given your life for King and Country.

You will also be proud to know that Royalty has been rubbing shoulders with you for decades. Members of the Royal Family and indeed other famous people often boarded their train from platform one, from where you now stand. My colleagues and I spent many hours keeping the Royal Train safe and escorting the various dignitaries, but you’ve probably been watching all these comings and goings for years.

You’ve probably also watched the unsavoury things in life that occurred right under your nose, the vagabonds and ruffians who frequented the station to commit crimes. Nothing much has changed since you were a boy.

My grandad served in the Great War and whilst he spoke little of his experiences fighting abroad, I did find out years later some of what he went through. Having served in the Boer War in South Africa he went off to fight again in 1915 in the Gallipoli Campaign. Although he was seriously injured fighting overseas he fortunately survived to be repatriated to the UK and to live to a good age.

So Tom I can imagine what you may have gone through. But unfortunately you didn’t have the chance to see your grandson, like my grandfather did. So I’d just like to say to you, thank you for sacrificing your life for my generation to be able to live in peace. I and very many more people will always be eternally grateful to you and the many millions of your comrades who gave up so much.

Tom, as I am now retired, I may not be passing you at Paddington Station very often these days, but I will never ever forget you as a great bloke and a very brave soldier.

Thank you Tom and God Bless You.

John Owen

68, Grantham, British Transport Police History Group, Retired

Letter from the Unknown Soldier

I am not able to write adequately about the people and the country of France. Whatever one sees is different from our Punjab villages. They have here pleasant gardens, houses made from bricks, roads and carriages. The soil is beautiful, corn or roses would grow quickly if planted.

We are treated well and given blankets and food, even a scarf which I am now wearing to help me fight the cold weather. The bread is like a baton which is hard on the outside and soft in the middle, it is acceptable. We are eating of the salt of the King and loyalty becomes us.

Yet all around us are scenes from the wars in the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. So I take heart from your words, that Time is ruled by God, that my breath is in God’s will. But how I grieve for you, for all at home, that the plague is spreading. You are ever before my eyes. What more can I say.

Letter to the Unknown Soldier

How strange to receive your letter written not in Punjabi but in English. And here I am writing in foreign. Our reader and writer is a kind Brahmin in town who charges little. I have to tell you, it is true, as you must have heard from the other soldiers, the plague has come like a scythe to corn and is spreading from village to village for its grim crop! We remain safe and have turned to the snake priest who sprinkles the houses with fire to ward off evil; we make daily puja at his shrine. Dear husband, remember God is everywhere, his will is in the drinking water which becomes holy when you drink it with a prayer.

The rains have come so do not worry for the crops. The cow is giving milk and we have a good store of corn. I hope you are being treated well, that you are given our food and that foreign is green with mountain water as we have it here. The name of the German is breathed like that of the demon Harankash. There are rumours he is coming to Punjab but we know the King will send him packing.

How soon married, how soon we have been parted. I must not forget your smile and your always kind words. My husband, fight like a man and come home a hero with the shadow of God in your stride. What more can I say.

Daljit Nagra

Harrow, Writer

Dear Boy

I can’t stop thinking about you as you head off for the great adventure in France. You look very marvellous in your uniform: it is funny how a uniform turns a boy into a man so quickly.

I just wanted to say goodbye properly before you leave on the train, to remind you that even though you are excited now, things will change; and sometimes you will feel very wretched and frightened and not bright and happy as you were when the train pulled out of the station and you were all singing and waving your caps.

Always remember that you must take care of your friends and mates who will be having a rough time as well: try to keep your spirits up, even when it looks darker than hell. I don’t know how sorely you will be tested but at all times be as brave and kind as can be. I have put some cough lozenges in your kitbag and a vest for when it is cold. Remember to read, as that will take your mind off the guns. Look out for birds and flowers, as they are the signs that in the end all will be well; and if you meet local people please be polite (Bonjour, merci, au revoir).

Will you write to me? Writing is like an escape, and that is why I am writing this now, as I think that if I saw you I would cry my eyes out at having to say goodbye.

I don’t know what will happen, but every day and every moment I will be thinking of you, my Boy.

Come back safely xxxx

Your loving mother

Joanna Lumley

Actor

I wanted to express my gratitude … is what I find myself writing from habit. I’m not sure gratitude is the right word, because I’m not too sure I’m for the war, or any war for that matter.

And I’m not sure whether you’re out there by choice or by duty or if the two can ever be intertwined. I could talk about home or ask you what it is like out there, in the mud and the cold and the rain. I could talk about the women down the road sewing as if it will mend everything, or about my widowed neighbour who stares forlornly at the forget-me-nots in her garden and no longer speaks, not even to the milkman. But I don’t think these trivialities will put light in your heart and it is light in your heart that might pull you through the struggles that arrive with each new day. So I will tell you a story with the aim of spiriting you away to a gentle place …

After a while all the cold mud grows warmer, and the air hot. Rainforest plants appear, thick and moist and green, and they open to a lake from which steam rises. All around birds of paradise sing.

The butterflies float iridescent in the humidity and the bright tree frogs gaze longingly at the flies. A beautiful person swims there, in the lake, every day, at the foot of a ramshackle jetty which rises from the door of a house made of reeds to the bank. This ethereal being kisses the water as it flows past their nakedness. Time subsides. Reaching the bank, they raise their body glistening from the water, drawing their legs up to their chest. And then their eyes, like other fantastical worlds, invite you to join them, as temptation stretches out across the sand, waiting.

Sophie Collard

27, London, Writer

Darling

I don’t know if you’ll ever get this letter but I had to write it anyway.

Sorry for any spelling mistakes. You know I’m writing this quick and urgent as I need to catch the postman, and you know spelling was never my strongest was it, not never in school. But Roddy. I have to tell you, in case – well I can’t write it here – but you know what I’m thinking. I have to write so that I can think of you over there, with my words tucked up in your pocket next to your heart.

Of course your wife will write you too, going on about the boys and the socks she’s knitting and stuff like that. Everyone else is allowed to write you. Your mum. Jenny, Nanna. Everyone except me. But you know, don’t you, things I can’t never say? I have to say them. Otherwise my heart is going to crack right open like a walnut shell.

That day you left. The line you was in with the others – you remember me running alongside, and then stopping when I saw Alice. I was trying to tell you. Something I think you’ve guessed. And whatever happens, whatever – I won’t never get over you and I won’t never find another man if you don’t come back and I don’t care what anyone says about war and fighting but what we did was real too wasn’t it, what we did matters? It was true and ours, and it’s the only thing that matters in this world really isn’t it? It’s the only thing that lasts, that can save us – Roddy, darling, I have to tell you!

You’re a good man Roddy. I know you was scared that night and lonely and you wasn’t thinking about Alice and you didn’t mean to hurt no one it was just a long time we’d loved each other and not given in to it, wasn’t it, all those years in school and that, but for me it wasn’t like that at all. It wasn’t a mistake, no, and it wasn’t the war neither. It was the most special thing I’ve ever done. It will always be that to me. So Roddy, I won’t tell a soul, all right, I promise. I just wanted to write you this letter. I’ll raise her or him by myself to be a good person I won’t let him go to war neither if he’s a boy or maybe I will if it’s a good cause, right, like what you’re doing. I’ll do a good job I know I will – I always wanted to be a mother.

I can bear anything, I’ll go away to a home to have my baby, I won’t bring a scandal, I’ll raise him right – I hope it’s a son Roddy, I hope he grows up into a good man like you – I’ll bear whatever people want to throw at me.

If only you’ll keep safe Roddy. Please, Roddy. Just keep yourself safe and come back.

Your loving Ruby

xx

Jill Dawson

Ely, Writer

I think there were a lot of women who suffered in silence about losses because they weren’t recognised as girlfriends, wives or mothers, because their hearts contained secrets. Women who couldn’t mourn openly. I think someone I know – now ninety-two – is one such woman. I wanted to write a letter from her.

Dear Unknown Soldier

What a stupid statement. I know exactly who you are. So if I know you, then you cannot be unknown – well not to me anyway.

I never met you. You had gone to fight in that terrible, terrible war many years before I was born, but that doesn’t make any difference.

I grew up knowing that you – my great-uncle – had died in Belgium, fighting over some unpronounceable woods, and that you had been ‘killed in action’, at least that is what the telegram said. A telegram that my grandmother, your sister, took from the ashen-faced telegram boy.

‘Killed in action’ the telegram said, but what it didn’t say was that you had probably been atomised. There was no recognisable trace of you left to bury. No grave for us, your family, to mourn over.

Yes I know your name is on a wall, which is on a panel and which makes up the focus of remembrance that is the Menin Gate, in Ypres.

The Menin Gate – the British Memorial to the Missing – and you are not alone.

Alongside you are the names of 54,338 other poor souls who like you, ‘have no known grave’.

I like to think, as I stand below your name, that you are aware of who I am and that I am there on behalf of the rest of your family.

Your family. Did you know that your mother, father and youngest sister Ethel had travelled to Belgium in 1928, as pilgrims on the then ‘British Legion Pilgrimage’? They had stood beneath the same panel that I have. Did their tears make you weep?

I’ve often wondered whether even for the briefest of moments, you could have left your panel and wrapped your arms around them. A family, together again.

Your mother never got over your death. Her grief was absolute. The love your mother had for you and the spectre of grief that had wrapped itself around her, escorted her to the grave.

How cruel is fate? I truly hope that you were aware that your father departed this life on September 29th 1938 – twenty years to the day that you departed. How symbolic was that.

As I write this, I am looking at a photo of you, taken when you were a young man; a young man who seemed full of life and yet who was to have that life cruelly taken from him – and us.

I freely admit that the statue of the unknown soldier doesn’t look very much like your photograph, BUT IF I WANT TO BELIEVE THAT IT IS YOU, THEN THAT’S WHAT I’M GOING TO BELIEVE!

Until I write again, I’ll leave you with the final line from one verse of the hymn, ‘Jesus, Lover Of My Soul’:

‘Safe into the haven guide; O receive my soul at last.’

God Bless You

Your Great-Nephew

Gareth Scourfield

67, Caerphilly, Royal British Legion and The Western Front Association, Retired

This letter is my chance to write to my great-uncle, who was Killed in Action in September 1918.

Brave soldier, perpetual myth:

The sacrifice slaughtered on

politician altars and citizens

needing a quick idol. ‘Look

how much better – look

how much worse –’ You,

soldier martyr and Saint

Patriot, named but by your

nation and known but by your

cliché: You journey forth bold

and confident (how else would

you go?), and die a death

cinematically heroic. Fears

dismissed, doubts diminished –

And have I said it yet?

Thank you for dying.

Thank you for dying.

Have you heard about the Xbox?

Thank you for dying.

Thank you for dying.

Take it on assurance, this

is how you wanted it – death

made meaningful in strangers’

memories (and maybe it’s

true, maybe we do preserve

you in fleeting thoughts meshed

between ‘I’m hungry’ and ‘Hey,

there’s McDonald’s’). But

when ‘sacrifice’ is pandered

beside ‘LOL’ and ‘like’ and the next

Big Issue, does the word not

lose its value? Cheap and rendered

meaningless in repetition – And have I

mentioned you must be handsome,

strong, and honourable; what other

kind of soldier is there? And maybe

you are that way, maybe –

You are that soldier’s ancestor, the one

who talked the woman and kids trapped

in their house through eight hours of Taliban

shooting, the soldier who would not

let her hang up and face it

alone. But maybe you weren’t, maybe –

you are more like those who say

they would shoot any Afghan;

who cares if she’s pregnant?

Maybe you swear and drink

and women fight instead of fancy

you. Is it blasphemy to say:

One does not become a hero

simply by having died?

Unknown but claimed by everyone,

you’ve lost your identity, sir,

it belongs to us, sir, to make

not into a mirror

but a manipulation. You

are mine to say ‘noble.’ You

are mine to say ‘tool.’ You

are mine to say ‘hero.’ You

are mine to say ‘waste.’ You

have no voice. You

have no memory. You

are mine to make a myth.

Alyssa Hollingsworth

23, Fort Monroe, USA, Bath Spa University, Graduate Student

Dear Soldier –

I see you there. You are gripping that letter, and you are angry.

We are asked to remember, but it isn’t easy. I have no experience of war and what it does to you, even though the troops – the British, the American, the Syrian, the troops in so many countries, in fact – are engaged in war almost continually. The closest I’ve come to your war is the memorial in Ely Cathedral; my great-uncles, W. A. Low and H. Low, both killed at the western front, are named on it. I didn’t know those uncles. My mother, their niece, didn’t know them either; they were killed before she was born.

My grandfather – their brother – left England during your war; he married my grandmother, fled the Fenlands and travelled to Canada, beating conscription and thus avoiding their fates. He died before I was born. I look at you on your plinth, soldier, and I think: how can I remember people I never knew? How can we know the unknown soldier?

My family has no artefacts, no touchable, tangible family history. When my mother died and we emptied my parents’ house, the only remnant of their parents’ generation was a badly made plywood plant-holder that my grandfather, a railway worker, knocked together in the 1950s.

A railway worker, like you. But alive and well in 1918, the year, perhaps, you lost your life; head down, hard at work, making a new family on a big lake in a fertile valley in the westernmost reaches of the new Dominion, far far away from Europe and the dirt and the blood and the horror. Eventually, he built a house for that family to live in. They thrived. My mother married a man who had been to university.

But you, you died on a battlefield. You got more than you bargained for, I imagine, like W. A. and H. You stand there, gripping that letter, and you are angry. You look up, away from the letter, at us, all the people, one hundred years later, and you open your mouth and you roar. You roar at everyone gathered at the cenotaphs and memorials, you shout at everyone with their speeches and their sermons and their poppies and their wreaths, and you fill those minutes of silence. You want us to listen to your message.

But we don’t hear you. We drag our suitcases up the platform past you and we look at our phones and we worry about missing the train, and we do not hear what you are saying. And the troops are deployed, and re-deployed, all over the world, again and again.

Kate Pullinger

London, Writer

Tommy reads his orders

And despite his greatcoat,

Feels the cold inside his brain.

How to tell his friends?

There’d been no training for such a job.

That they must go over the top again.

If a friend fell beside him,

What then would he say or do?

Would he stride on as taught

Or stand like a statue waiting for a train?

Richard Ireson

67, Romford, Pensioner

My maternal grandfather fought in WW1. Dedicated to all who fought.

Dear husband

It feels almost normal now, these letters, our only communication since countless months, or perhaps years? I read and re-read your every word till I have memorised not just the words but even the rise and fall of your lettering; the winding ink trails carved in your strong hand, every bit as sacred to me as the holy Alaknanda and Bhagirathi rivers that carve through and feed our land, just as your words feed my soul.

Do you remember, as children, I would watch you playing with your friends, scrambling over the rocky banks of the Bhagirathi, claiming the land in the name of the Shah? Afterwards, you would come back home with me, and we would swing on the rope swing hanging from the mango tree in the courtyard, where I sit again now, remembering and writing. You talked even then about teaching our children to climb and pick the mangoes.

Who knew then that just days after our marriage, the foreign King would need you to go to strange lands and fight his war? Did he not realise that there were others who needed you more? We who fight our own daily battles, for whom life itself has become war. But who thinks of us? Not this foreign King, not the foreigners whom your blood and sweat defend. Who will remember us, unknown soldiers of an unknown war?