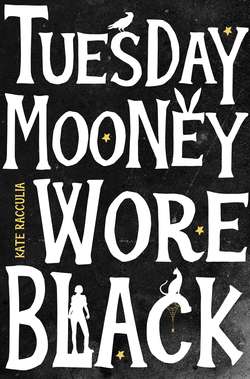

Читать книгу Tuesday Mooney Wore Black - Kate Racculia - Страница 14

5 BLOODY MARYS

ОглавлениеFriday.

Tuesday’s alarm went off at the usual time. Her arm shot out from a mound of duvet and smacked Snooze with a great deal of violence.

Before any discernible time had passed, it went off again.

And this time she remembered the night before.

Her brain sprang to life, dinging like a pinball machine. She had chased Pryce’s clue into the bowels of Park Street – ding! – and found a secret code – ding! – with a wealthy, obscenely attractive stranger – ding-ding! – who also – ran away and left her to the cops?

Had that really – had that—

She pulled her duvet up and over her face. Her lips cracked into a demented grin. Tuesday, alone in her apartment, cocooned in her bed, began to laugh. It came out first like a strangled hiss, air pushing between her clenched teeth, but the more she thought about it, the more absurd – she was exhausted, but it was – she was – her head was full of helium. The laugh pushed itself up and out into a full-throated cackle.

Tuesday Mooney was awake.

And now that she was awake, she had some decisions to make. Like: Should she call in sick? Or was calling in sick delaying the unavoidable; was it better to suck it up and get the worst of the “yes, that was me you saw on the internet in handcuffs” conversations out of the way before next week?

She stopped laughing and sat up straight.

Her parents.

It was too early to call her parents. Any call from her before eight a.m. would scare the daylights out of them, but she should probably try to talk to them before they saw it somewhere. Complicating matters was the fact that her parents had recently discovered Facebook. At her brother’s insistence, they’d created a page for Mooney’s Miscellany, which was really a way for Ollie to post pictures of the rare action figures he traded and sold out of the store on weekends. Her father thought Facebook was hilarious – “Six people liked what I had for breakfast. What a world!” – and her mother mostly used it to take personality quizzes. “Guess what?” she’d say, as though passing along hot intel. “If I were a Muppet, I’d be Gonzo.”

Did they look at Facebook at home before opening the store at ten? She didn’t know. She turned off her alarm and glared at her phone. She could check her own Facebook app and see how bad it was. She loved the internet, but she loathed feeling so fucking available. So exposed. And so goddamn distracted.

Gunnar howled from the kitchen.

She didn’t want to call them.

She didn’t want to have to explain any of this. She already knew what they’d think, even if they didn’t say it. Especially if they didn’t say it. It would ooze into all the cracks and crevices between their words.

And they would be right, this time, to be worried.

Her phone rang. The screen filled with a picture of her parents’ dog, Giles Corey III, pressed to sleep under a mound of couch cushions.

She slid her fingertip across the phone.

“Is this my daughter the terrorist?” her mother said. Sally Mooney had a voice like dark maple syrup, sweet and deep. And she was Gonzo; she invented strange, mostly useless things (an automated toast butterer, a case for golf pencils) and held firm beliefs about the healing powers of various Stevie Nicks songs. Tuesday didn’t need an online quiz to tell her that her mother was a weirdo.

“I was really hoping I could break it to you guys,” she said.

“There’s this thing, dear terrorist daughter, called the internet. It’s faster than the speed of a daughter’s admission of guilt.”

Tuesday tucked herself farther under the covers. “I don’t feel that guilty. Lucky, yes. And ashamed, maybe? That I got caught.”

“It’s true, we raised you to be slipperier than that. Are you okay? Ted – Ted, pick up the phone. It’s your daughter the terrorist.”

The line crackled and her father’s higher voice – nerdier, brighter, the voice of an overly enthusiastic cartoon squirrel – broke in. “You say terrorist, I say anarchist. Moonie! What the hell happened?”

“I—” And here it was: the wall. When asked for an explanation, Tuesday found herself unable to provide the truth, whole and unvarnished.

For a variety of reasons. Despite being on social media, they weren’t tech savvy; they wouldn’t know how to tweet Archie’s involvement to the world (not that she felt any great desire to protect him at this point). But every time she so much as glancingly mentioned a man, in any context – Pete, her mail carrier; Alvin, her bus driver; Fancy Hobbit, the short, curly-haired, bowtie-wearing stranger she saw most days on her commute – both of her parents turned into giggly preteens. For as resolutely nontraditional as they both claimed to be, for all the talk of dream-divining and heart-following, and the gently radical dogma that had permeated her childhood (the fourth little pig lived off the grid, which is why the wolf never bothered him in the first place), when it came to the question of relationships, a conservative streak ran deep. They only wanted her to “fall in love,” to “be happy” – as if the only way she could possibly be happy was by securing an explicitly sexual romantic partnership – but she wasn’t looking for excuses to get their hopes up, particularly when their hopes were theirs and not her own. So she said:

“Dorry and I figured out the clue. How could I not go for it?”

Elision was the best kind of lying. You didn’t even have to lie, just selectively tell. She selectively told them about the editorials, the hideous hearts, the raven in Park Street. She told them about the clown mannequin.

She did not tell them that it had, for a moment, worn the decaying face of Abby Hobbes.

“Oh Moonie,” said her dad, who had never forgiven himself for hiring a clown for her third birthday. “I am so sorry.”

Her phone buzzed against her ear.

It was Dex: guess who’s on the front page of the metro.

She felt her entire body try to sink into her mattress, desperate to become one with her bed.

Gunnar galloped the length of the apartment and sprang onto her feet. Then he sat, deliberately thumping his tail, flattening the duvet, and stared at her.

“The world is telling me I have to get up and get this over with,” she said. “I promise not to make too much more trouble.”

“Don’t make promises you can’t keep,” said her mother. “But be careful. You know you’re our favorite daughter.”

“I’m your only daughter,” she said. They’d been reciting the same joke, like a benediction, ever since Tuesday was old enough to understand why it was supposed to be funny.

“Moonie,” said her father, the brightness of his voice dimming. Tuesday pulled the duvet back over her head. There was never any question of telling them that she’d seen and heard Abby – never, ever would she do that – but she didn’t have to. Abby was always just below the surface.

“Be careful,” he said, “only daughter.”

An hour and change later, though only nominally more awake, Tuesday swung into her cubicle. She set the first of what would necessarily be many, many cups of coffee on her desk, and noticed someone had taped the front page of that morning’s Metro to her computer monitor. Under the headline TREASURE HUNTER IN THE HUB was a full-color photo of her