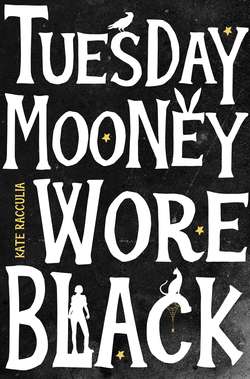

Читать книгу Tuesday Mooney Wore Black - Kate Racculia - Страница 8

THE OPENED TOMB

ОглавлениеThe Tillerman house was dead. Over a century old, massive and stone, it lay slumped on its corner lot, exposed by the naked December trees and shrubs growing wildly over its corpse. It was ugly, neglected, and, despite its size, withered; a black hole of a house. If the real estate agent were the kind of person who ascribed personalities to properties – he was not – he would have said it was the loneliest house he had ever sold.

His instincts told him this would be a strange, quick sale, with a giant commission. When he’d told the owner that, out of the blue, they had a buyer for the Tillerman house, some guy named “R. Usher,” the owner said, after a long pause, “Don’t sell it for a penny less than listed.” But the agent was anxious to get this over with. He had been inside the Tillerman house once before, and he hadn’t forgotten how it felt.

A figure appeared on the sidewalk, rounding the corner up the street. The agent shielded his eyes against the white winter sun to get a better look. A man. Wearing a long black coat and a giant black hat, broad and furry, something a Cossack might wear against the Siberian winter. The real estate agent smiled to himself. Yes. This was exactly the buyer you wanted when you were trying to sell a haunted house.

“Hello, young man!” said the figure, waving, ten feet away now. “I assume you’re the young man I’m supposed to meet. You are standing, after all, in front of the house I’d like to purchase.” A bright red-and-purple-plaid scarf was looped around his neck, covering the lower half of his face. He pulled the scarf down with a red mitten to reveal a ridiculous curling white mustache. “Young man,” said the buyer, “allow me to introduce myself. Roderick Usher.” And he held out his hand.

The agent, while technically younger than the buyer, resented its being pointed out to him. He was years out of school, up and coming in Boston real estate, and, yes, selling this property for the listed price of $4.3 million would be a coup, but he wasn’t a young man. He was a man. He shook Mr. Usher’s hand and gestured to the property. “Shall we go inside?” he said, and pressed the quaver out of his voice.

Dead leaves crackled beneath their shoes as they walked under the portico and up the front steps. The lock to the Tillerman house was newly installed, but the key never wanted to work. The agent turned it to the left gently, then the right, then the left again. “What a beauty she is,” said Mr. Usher, his hands clasped behind his back, head tipped up to take in the carvings around the door, flowers reduced to geometric lines and patterns, a strange mishmash of Arts and Crafts, Nouveau and Deco, that didn’t jibe with what the agent knew about when it was built. It was almost as if the house had continued to build itself long after it was abandoned. “If she’s this lovely on the outside,” said Mr. Usher, “I can’t imagine what—”

The lock turned at last, and the agent pushed the door open.

The first thing that struck him was the smell. Of rot and garbage, of meat gone rancid, of animals that had been dying in the walls for decades. He pressed the back of his suit sleeve to his nose without thinking, then lowered it, eyes watering. The house had no electricity – when it was first built it did, but the wiring hadn’t been up to code since Woodrow Wilson was president – but it did have enormous ground-floor windows on one side of the great hall, which cast light throughout the first floor and down into the vestibule. It was enough to see by. It had been enough, on the agent’s previous showing with a buyer, for the buyer to take one look around and say, “Let’s get out of here now.”

Let’s get out of here now, said the agent’s brain.

“What a glorious – oh – oh my!” said Mr. Usher, and swept past him into the house. He took off his giant furry hat, clutched it in both hands at his chest, and spun back to the agent. Grinning. His front teeth were large and crooked. “My goodness, do you know what you have here? Can you feel it?”

He didn’t wait for the agent to answer, and charged up the steps, through the archway, and into the great hall.

The agent followed, slowly. His feet did not want to move. It was exactly what had happened to him the last time he entered the Tillerman house: his body did not want to be here. An uncontrollable part of his brain – his otherwise rational, adult brain – reacted to this place as though he were six years old. Six years old, and pissing himself on Halloween because his big brother, in a scuffed and stage-blood-spattered hockey mask, leapt out at him from the dark.

He cleared his throat. Took the steps one at a time. Until he was standing in the half-dusk of the great hall. Mr. Usher, who’d been dashing around the room, turned back to him.

“She died here,” he said. “Can you feel her?”

The agent managed something like a smile.

“Long, long ago, you came to Matilda Tillerman’s,” Mr. Usher continued, “she, the last surviving heir of all that Tillerman wealth – you came to her house to drink and to dance, to laugh and to talk, to be alive, together, in this glorious house. They all came here, were well met here, from every corner of this city, every nook and cranny. But something happened, nobody can say for sure what, and Matilda shut her doors. Shut out the entire world and made of her house a tomb.” He sighed and laid a hand gently on one of the columns supporting the upper gallery. “And a beautiful tomb it is.” Plaster flaked beneath his fingertips.

He tipped his head to the side. “Young man,” he said, “I’m going to buy this house. I won’t keep you in suspense any longer, so you can stop looking so frightened. But I would ask a favor. I make it a point of putting a serious question to a man whenever I meet him. Would you permit me?”

The agent, relieved to the point of tears that this showing was nearly over, would have permitted the buyer anything. “Yes,” he said. “Of course.”

“Marvelous.” Mr. Usher dropped his furry hat to the floor. It sent up a puff of ancient dust. “I have lived for a good long while. Enough to have borne the world,” he said. “And sometimes, the world is far too much for me. Too great. Too painful. Too lonely. I expect, if Ms. Tillerman will allow me to interpret her past actions, she may have felt the same. Is it selfish then, or self-preserving, to shut oneself away? At what point does one give up, so to speak, the ghost?”

The agent swallowed. He didn’t know what to say. No one had ever asked him a question like that before. It made him almost as uncomfortable as the house. It was too personal. It was too—

He had, once or twice, imagined it. How it would feel to say, to his bank account and his car and his condo and his girlfriend and his job, Go away. Leave me alone. So he could rest, and listen, and think, and maybe have a chance, one last chance, to remember what he’d been meaning to do before all this life he was living got started.

“I’m not sure,” he told Mr. Usher, “what to say.”

“An honest response,” Mr. Usher replied. “I appreciate that. I—”

A gust of frigid wind howled through the still-open door and lifted clouds of dust and spider webs from the walls and the floor. Delicate debris filled the air. The buyer coughed. Then the breeze caught the door and slammed it home with a crash.

The agent felt his entire body electrify. Mr. Usher jumped, and laughed.

Then: a second crash.

Smaller, closer, nearby in the house, off to the right. The agent’s body twitched violently and he doubled over, hands on kneecaps. He couldn’t stay here. This house was too much for him. He heard Mr. Usher walk across the great hall and pick something up off the floor and mutter to himself. Oh, you clever house, the agent thought he heard. What else are you hiding?

“Come on, dear boy,” said Mr. Usher, suddenly at his side, helping him upright and clapping him gently on the back. “It’s enough to frighten anyone, opening a tomb.” He smiled, the curls of his mustache lifting almost to his eyes. “Makes one feel a bit like Lord Carnarvon.”

The agent didn’t know who that was.

“Best hope there’s not a curse,” said Mr. Usher, walking back down the steps toward the door and the light, “for disturbing her.”