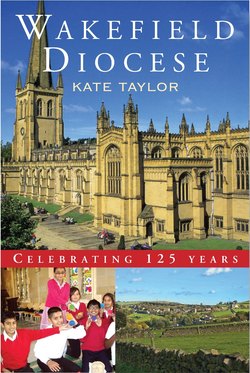

Читать книгу Wakefield Diocese - Kate Taylor - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPart I: The First Fifty Years, 1888–1938

The Origin of the Diocese

The Diocese of Wakefield was established in 1888, taking in a substantial area from the southern end of the Diocese of Ripon. It had been a long time coming!

Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, no new bishoprics had been established in the Church of England. Then came the Dioceses of Ripon (1836) and Manchester (1845). By 1875, the population of the Ripon Diocese had doubled, from 800,000 at its inception to 1,600,000. With a vast distance to cover and with so many parishes to visit, the health of the second Bishop of Ripon, Robert Bickersteth, was under strain. Moreover, Nonconformity was flourishing. It was later said that the immense success of early Methodism in the Calder valley owed something to the deadness and dullness of church life in the area, but it must have owed considerably more to the influence of the ‘wealthy capitalists and employers of labour’ who, Francis Pigou, Vicar of Halifax in 1875–88, observed, were a strong influence on the spread of Nonconformity in the area. Evidence suggesting that smaller diocesan units resulted in greater numbers of men coming forward for ordination and in more candidates for confirmation was a further incentive to create additional dioceses.

The genesis of the Diocese of Wakefield falls into two distinct phases: the first culminating in the Act of Parliament of 1878 which authorized the establishment of a Wakefield see; the second, dating from 1884, bringing the Diocese into being by the Order in Council of 17 May 1888.

For any new diocese to be created a very substantial capital sum was needed to endow the bishopric. The Bishoprics Act of 1878 specified a minimum income of £3,500 a year.

Although there had been earlier suggestions that a new see should be created with Halifax as its cathedral city, it was the death of Charles Musgrave, Vicar of Halifax and Archdeacon of Craven, in April 1875 that prompted moves to create a further bishopric in southern Yorkshire with Halifax parish church as the cathedral. It was thought that some £100,000 would be required. The Halifax living was a substantial one. There seemed a possibility that some of the endowments of the benefice could be appropriated, by means of an Act of Parliament, towards financing the bishopric. A leading advocate of a Halifax diocese, industrialist Sir Henry Edwards (1812–86), who had represented Halifax in Parliament in 1847–52, suggested that, rather than appropriating funds from the living, the diocesan of the new see should also be the Vicar of Halifax. The idea was canvassed at a meeting in London attended by several Members of Parliament, but the scheme came to nothing and later in 1875 Francis Pigou was appointed to the Halifax benefice. However, when the Ecclesiastical Commissioners set up a committee to define the boundaries of the proposed bishoprics of Truro and St Albans, it was asked to look at the need nationally for other new bishoprics. The committee included the Conservative West Riding Member of Parliament, Lieutenant Colonel Walter Spencer Stanhope. Its initial recommendations were for sees centred on Liverpool, Newcastle and Southwell. When, following its deliberations, the Bill was first drafted in 1877, a diocese of South Yorkshire had been added which would have included Sheffield (not part of the Diocese of Ripon) as well as Halifax and Wakefield and places between. The prospect of being severed from York did not appeal to the church people of Sheffield and, when the bill finally came before Parliament, Sheffield had been dropped from it but the South Yorkshire scheme remained. The Government’s first intention was to identify Wakefield as the cathedral city. Following an intervention from Sir Henry Edwards, the Bill proposed either Wakefield or Halifax as the cathedral city, leaving the final decision to the Queen in Council.

There was what the Wakefield Herald described as a ‘monster meeting’ in Wakefield on 23 May 1877, with leading civic as well as church figures there, to seek formal support for ‘the superior claims of the town’. The Mayor of Wakefield, Alderman W. H. Gill, took the chair. The Vicar of Wakefield, Norman J. D. Straton, and Wakefield’s Conservative Member of Parliament, Thomas Kemp Sanderson, were on the platform together with Lieutenant Colonel Stanhope. Alderman Gill referred to his meeting with the Home Secretary to press the claims of Wakefield. Stanhope expressed concern that, if the see were centred on Halifax, the bishop would have a lower status than the vicar as the latter had some thirty livings in his gift and the new bishop would certainly have far fewer. Wakefield people had already undertaken a major restoration of the parish church. There had been no comparable work at Halifax. Sanderson, pointed out than in 1836 there had been the possibility of Wakefield being the cathedral city rather than Ripon. Moreover, Wakefield was not, like Halifax, merely ‘on a railway branch line’. A sum of £100,000 was again identified as necessary to endow the bishopric. A number of Wakefield people promised individual donations of £1,000. Sanderson proposed, ‘Inasmuch as the Bill empowers Her Majesty by Order of Council to make choice between Wakefield and Halifax as the cathedral city for the proposed new diocese, this meeting desires to express its sense of the superior claims of Wakefield and hereby prays Her Majesty to select the former place.’ It was, of course, carried.

A similar meeting in the New Assembly Rooms in Halifax on 25 May, convened by Sir Henry Edwards, was less well attended. Edwards explained how he had lobbied successfully to have the option of Halifax added to a bill that originally referred only to Wakefield. The meeting secured unanimous support for a motion urging that Halifax be chosen as the cathedral city, citing the possibility of an easy adaptation of the parish church and the strategic situation of Halifax geographically and in terms of railway communication within the projected diocese. But the Halifax Courier noted ‘something like mutiny in the Halifax Camp’ because a number of the poorer vicars in the Halifax area thought that any surplus money that might still be appropriated from the vicar’s endowments should be directed to improving their livings rather than financing a bishop. The paper foresaw that the cathedral would as a consequence be in Wakefield. A committee was appointed, with Edwards among its members, to promote the claims of Halifax. Edward Balme Wheatley-Balme (1819–96) however, who was not at the meeting, sent a message that he would give £5,000 towards the bishopric fund whichever town was chosen.

Wheatley-Balme, who lived at Cote Wall, Mirfield, was ultimately the single most significant donor to the bishopric, giving some £10,000. When, before the diocese could be founded, the Ecclesiastical Commissioners required four guarantors to ensure that a house would be provided for the bishop, he was one of these. When the Wakefield Diocesan Conference was first set up, Bishop How chose him as one of his personally nominated ten members.

Huddersfield was never in serious contention as the cathedral city, and a meeting of Huddersfield clergy, again in May 1877, accepted that the honours would go to Wakefield.

The persistent advocacy of Wakefield’s MP, Thomas Kemp Sanderson, went a long way to furthering Wakefield’s cause where the two Radical Halifax members (James Stansfeld, a radical protestant dissenter, and John Dyson Hutchinson) remained detached. Pigou noted that they were more interested in pursuing the disestablishment of the church than in creating a new diocese. Pigou was asked by the then Home Secretary, Richard Assheton Cross, to give his opinion on the relative merits of the two towns for the see. At their meeting he was told by Cross that the petition of the clergy against Halifax, fearing that money that might have been used to improve their benefices would be diverted to the bishopric fund, sealed its fate. The claims of Wakefield were preferred. When Sanderson was given the Freedom of the City of Wakfield in 1895, the citation referred to its being ‘in great measure’ due to him that Wakefield had been chosen for the cathedral.

The Bishoprics Act, passed in 1878, provided specifically for a Bishop of Wakefield as well as for the anticipated sees of Liverpool, Newcastle, and Southwell. The cathedral would be, ‘Such church at Wakefield as may be determined by order of Her Majesty in Council subject to the rights of the patron and incumbent.’ The new bishopric was to have such a part of the endowment of the Bishopric of Ripon as would bring in £300 a year.

Halifax Minster, Chris Lord Photography

The historic significance of Halifax Parish Church was recognized when in 2009 it was given minster status. The accolade was celebrated at a service in November.

But although an Act of Parliament now provided for the South Yorkshire see, for some years the matter was dropped. There was an economic recession affecting both agriculture and commerce. Although the Diocese of Liverpool was formed in 1880 and that of Newcastle in 1882, there was no progress for some years on the Wakefield scheme.

Two things in 1884 prompted a second campaign to secure the new diocese. The first was the establishment that year of the Diocese of Southwell. The second was the death of Bishop Bickersteth and the appointment of William Boyd Carpenter who was consecrated on 25 July 1884, to the Ripon see. One of the key figures in reviving the scheme and in ensuring a successful conclusion was the Vicar of Wakefield, Norman Straton, who, new to Wakefield in 1875, was by 1884 one of the leading churchmen in the Ripon Diocese and had become a Canon of Ripon in 1883. The other most significant figure was Joshua Ingham Brooke, who had been Rector of Thornhill since 1867, and Rural Dean of Dewsbury since 1871, and was, like Straton, a Ripon Canon.

In 1884, Straton conceived the idea of bringing the (national) Church Congress to Wakefield in 1886 as a means of promoting the Wakefield scheme and adding to the funds. The Congress founded in 1861 in Cambridge, was a voluntary gathering bringing together Anglican clergy and lay people, and embracing Evangelicals, Ritualists and the broad church party. Straton obtained support at a public meeting in August 1884 to request the Bishop of Ripon to secure the next Congress for his diocese.

At Bishop Boyd Carpenter’s first Diocesan Conference, held in Leeds on 11 October 1884, Francis Sharpe Powell, a former Member of Parliament for the West Riding who had strongly supported Halifax’s claims in 1875, raised the subject of the division of the diocese and ensured the carrying of a motion asking the bishop to name a committee to raise the necessary funds.

Boyd Carpenter paid his first visit as bishop to Wakefield on 21 January 1885 to attend the annual Church Institution soiree. The event became not so much a social event as a campaign meeting at which the bishop was urged to exercise his good offices to secure the swift division of his diocese, in particular by driving the fund-raising. That June, Boyd-Carpenter wrote to all his clergy urging them to ‘do all in their power’ to secure the completion of the Wakefield Bishopric scheme. He subsequently visited many centres in the Ripon Diocese to foster the setting up of local fund-raising committees.

By the time of the Ripon Diocesan Conference in October 1885, Straton and Brooke as secretaries of the Wakefield Bishopric Fund had contacted all those who had offered subscriptions during the earlier campaign and succeeded in obtaining promises of £24,365. Straton was able to say, ‘Those who have hitherto regarded the erection of the Wakefield bishopric as an event which might possibly occur in the distant future must now be aware that it has come within measurable distance.’

The Church Congress, held in Wakefield in 1886, amply demonstrated the facilities Wakefield could offer as the diocesan cathedral city. It opened with a reception in the recently built Town Hall on 5 October followed by processions to the parish church, St John’s and Holy Trinity where services were held simultaneously. The trade floor of the Corn Exchange was converted into the Congress Hall. The Music Saloon in Wood Street and the Church Institute in Marygate were taken over by caterers. The offices of the Wakefield Charities in Market Street became a press room and the postmaster ensured that reports could be sent by electric telegraph to all parts of Britain. One of the country’s leading clerical outfitters exhibited his garments in the Co-operative Society’s store in Bank Street.

The Wakefield scheme had nothing like the financial support from wealthy merchants or landowners that other nineteenth-century bishoprics enjoyed. Wheatley-Balme was the only individual to contribute more than £1,000. Much of the money came from subscribers giving no more than a guinea. District Visitors and other collectors brought £645 from people who had little beyond pence to give. Offertories were held in many of the parishes of the Ripon Diocese. The sum from Huddersfield parish church was the second largest and amounted to £184. At Wakefield parish church the offertory was, at £175, the third largest. From Halifax, perhaps reflecting the disappointed hopes there, the offertory was fifty-second from the top of the table, a mere £18.

By 1888, the Wakefield Bishopric Fund had raised £83,510 19s 5d of which £79,857 was invested as an endowment. The Order in Council creating the bishopric was signed on 17 May 1888. It specified that All Saints parish church should be the cathedral.

The Diocese

The new diocese was created largely from the Ripon Archdeaconry of Craven but taking in also the parishes of Crofton, Warmfield and Woolley from York’s Pontefract Rural Deanery. It lay between Heptonstall, to the north-west, Halifax, Drighlington and Morley to the north, Penistone and Barnsley to the south, Ripponden and Marsden to the west and Warmfield and Wakefield to the east, and included the industrial towns of Batley, Brighouse, Dewsbury, Halifax, Holmfirth, Huddersfield, Mirfield and Ossett, The two greatest centres of population were Halifax and Huddersfield.

It had 167 benefices including the chaplaincies of West Bretton, and Stainborough. Between 1836 (when the Diocese of Ripon was founded) and 1888, 105 churches in the new diocese had been consecrated. Eighty-two of these were new parish churches. Thirteen were parish churches that had been rebuilt or built on new sites. A further eight were mission churches or chapels of ease. The most recent of the new parish churches were St John the Baptist, Daw Green (1886), Hartshead St Peter with Clifton (1886), St Mark’s, Huddersfield, and St Anne’s, Southowram (1887). St Luke’s, Sharlston, which was a daughter church in the parish of Warmfield, was also consecrated in 1887.

Those advowsons that had been held by the Bishop of Ripon or the Archbishop (as Bishop) of York were transferred to the successive bishops of Wakefield.

The diocese had six rural deaneries, more or less comparable to those taken from the Archdeaconry of Craven. The Ecclesiastical Commissioners had intended it to have a single archdeacon. However, the clergy in the new area petitioned them for a second and an Order in Council of 17 November 1888 provided for Archdeacons of both Halifax and Huddersfield, each to receive £200 a year from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. Straton, the Vicar of Wakefield, and the other of the two secretaries of the Wakefield Bishopric Fund, was promptly appointed as the Archdeacon of Huddersfield to be followed, when Straton became Bishop of Sodor and Man in 1892, by the new Vicar of Wakefield, William Donne.

The Rural Deaneries of Halifax, Birstall and Dewsbury came within the Archdeaconry of Halifax, and those of Huddersfield, Silkstone and Wakefield were allocated to the Archdeaconry of Huddersfield. (The Halifax Rural Deanery, by then with some fifty parishes, was given a second Rural Dean in 1914 for an experimental period.)

The November 1888 Order allowed for twelve honorary canons which were to include the four priests who had been Canons of Ripon or York but were now in the Wakefield Diocese. The two Archdeacons were instituted and the first eight Canons installed on 4 December 1888.

There was already one Religious Order – the Community of St Peter, Horbury – within the boundaries of the diocese. When the Community of the Resurrection moved to Mirfield in 1898, it gained a second.

The boundaries of the diocese changed as populations continued to grow and new dioceses were formed. The major change came in 1926 under the Pontefract and Hemsworth Deaneries Transfer Measure, when the diocese was extended and the Rural Deaneries of Hemsworth and Pontefract, which had been until then in the Diocese of York, were added. This brought a further thirty-five parishes into the diocese. The Rural Deanery of Silkstone was then renamed Barnsley, and the Rural Deanery of Pontefract was created. Midhope, which came into the Diocese of Sheffield at its foundation in 1914 but which was run in plurality with Penistone, was transferred to the Diocese of Wakefield in June of that year. Five years later, in 1919, the parishes of Tong and Wyke were transferred from Wakefield to the new Diocese of Bradford. When the Diocese of Blackburn was formed in 1927, from a part of the Diocese of Manchester, the parishes of Todmorden and Walsden were added to the Wakefield Diocese and the patronage of the two parishes was vested in the Bishop of Wakefield instead of the Bishop of Manchester.

Shortly after the 1926 extension of the diocese, the Archdeaconry of Huddersfield became the Archdeaconry of Halifax, and the hitherto Archdeaconry of Halifax became the Archdeaconry of Pontefract. The extension of the diocese provided an entitlement to six further honorary Canons.

The Bishops

Wakefield had three bishops in its first fifty years, William Walsham How in 1888–97, the long-serving George Rodney Eden, who was bishop in 1897–1928, and James Buchanan Seaton who died as the diocese celebrated its jubilee in 1938. After its major extension in 1926 made the assistance of a suffragan bishop highly desirable, Campbell Richard Hone, already the Archdeacon of Pontefract. became the first Bishop of Pontefract in 1931.

Wakefield’s first bishop, William Walsham How (1823–97), had spent twenty-eight years as Rector of Whittington, Shropshire (his father had purchased the advowson) before, styled Bishop of Bedford, becoming a suffragan to the Bishop of London and Rector of St Andrew Undershaft in 1879. He was consecrated in St Paul’s Cathedral on 25 July. In 1888, at sixty-four, and now a widower, How recoiled from the prospect of ‘spending his declining years in a region of smoke, of coal pits, and mill chimneys’ and shrank from the heavy task of organizing a new diocese, but regarded it as his simple duty to accept the challenge. He had a friend there already in Joshua Ingham Brooke, the Rector of Thornhill, whom he promptly appointed as his Archdeacon of Halifax. Another friend, William Foxley Norris, was presented by Sir John Ramsden to Almondbury in 1888. How’s son Henry became Vicar of Mirfield in 1889. How had been educated at Shrewsbury School and Wadham College, Oxford, before going on to Durham for a course in Theology. He was, for a new diocese, primarily a safe pair of hands. He was of high-church leanings but was not an out-and-out Tractarian: he conducted retreats and held quiet days, but he abhorred some of the ritual associated with the Oxford Movement. The education and welfare of children were among his prime concerns and he was one of the original figures named as a trustee for the National Society for the Protection of Children when it gained its royal charter in 1895. It was under his influence that the Church of England Society for Waifs and Strays founded a boys’ home, Bede House, in College Grove Road, Wakefield in 1892. He died on 10 August 1897 while on a fishing holiday in Ireland. Today he is best known for his hymns, in particular ‘For all the saints who from their labours rest’, which he wrote at Whittington and which was first published in 1864 in Hymns for Saints Days and other Hymns.

Bishop How

Unlike Bishop How, George Rodney Eden (1853–1940) had an accelerated career, at least until he reached Wakefield. He came from what used to be termed ‘a good family’, his grandfather, Sir Robert Eden, being the third baronet of West Auckland. He was educated at Richmond (Yorkshire) and Reading and gained a scholarship to Pembroke College, Cambridge. In 1879, shortly after his ordination as a priest, he was invited to serve as the chaplain to Joseph Barber Lightfoot, Bishop of Durham. Four years later he was presented to the living of Bishop Auckland. In 1890, he was consecrated at Canterbury as the Suffragan Bishop of Dover. He was still only forty-four when he was enthroned at Wakefield on 4 November 1897. He took his seat in the House of Lords on 27 February 1905 where he was regarded as an authority on education. He was for a time chair of the Education Committee of the Church of England National Assembly. In Wakefield, Eden was in the forefront of some of the social movements. With Walter Moorhouse, he established the Wakefield Sanitary Aid Society. Pressure from this body contributed to the local authority’s decision to clear the slums and build housing estates. With Edwin Hirst, he set up the Wakefield Garden Suburb Trust, acquiring a tract of land to the north of Dewsbury Road and then selling individual plots at modest prices to artisans or men from the lower middle class. An able administrator, he served at least once as secretary of the Lambeth Conference, staying for some weeks at Lambeth Palace. He retired in 1928 and spent some time in voluntary ministerial work in Egypt. An obituary in the Cathedral News in February 1940 spoke of the ‘keenness and shrewdness of that fine face and clear-set eyes’. A memorial was unveiled in the cathedral at the time of the Diocesan Conference on 8 October 1942.

Bishop Eden

Wakefield’s third bishop, James Buchanan Seaton (1868–1938), a bachelor and a moderate Anglo-Catholic in the Lux Mundi tradition, died in office. Seaton was a Yorkshireman to the extent that during the summer, he followed the fortunes of the county cricket team closely. He was born in Leeds and was educated at Leeds Grammar School where he gained a scholarship to Christ Church, Oxford in 1886. He took a Second in ‘Greats’ in 1890, and returned for a period to teach at Leeds Grammar School. He was made deacon in 1892 and priest in 1893. In 1893–96 he was a curate at Oswestry parish church. For the next four years he was the Vice-Principal of Leeds Clergy School (Leeds Theological College) before becoming Vicar of Armley in 1905–09. He spent the next five years in South Africa as Rector of St Mary’s and Archdeacon of Johannesburg before returning to Oxfordshire in 1914, as the Principal of Cuddesdon Theological College and Vicar of Cuddesdon. He was made an honorary Canon of Christ Church, the Oxford cathedral. Appointed as Bishop of Wakefield in 1928, he was consecrated on 1 November in York Minster and enthroned on 30 November. Spoken of as a man of ‘deep humility and boundless kindness and thoughtfulness’, Seaton was able to relate easily to the miners and mill workers of his diocese as well as to the professional classes, and made himself readily accessible to all. Seaton’s contribution in all his different spheres of work was not that of great achievements conceived and carried through, nor yet original enterprises in any particular direction. It was always and everywhere the same, namely himself and his personality. At the enlargement of the diocese in 1926, he set out to recruit more clergy and to obtain a suffragan bishop. He knew all his clergy well and entertained them at Bishopgarth. It seemed that he hated committees but loved working with young people. He held youth weekends at Bishopgarth for both males and females, hosting up to fifty at a time. He lived simply. He used to have his meals at a window in his study. He loved the Bishopgarth garden and enjoyed weeding the lawns. He ‘seldom said or did things that interested the press’, and was not a good platform speaker. He was, however, a keen supporter of the work of the church overseas and the translation of one of his young clergy to the See of Gambia must have given him immense pleasure.

The Cathedral

Under the Order in Council of 17 May 1888, Wakefield’s medieval parish church became the cathedral of the new diocese. Bishop How’s first ordination, of four deacons and two priests, took place there ten days later, even before his enthronement.

The installation and enthronement of the first bishop on 25 June 1888 was a major event both for the town and for the diocese, celebrated by the Mayor and Corporation as well as by the churches. It included a reception in the Town Hall when a series of illuminated addresses were read, and a lunch, presided over by the Archbishop of York, William Thomson, in the Corn Exchange before the procession to the new cathedral.

As a consequence of now having a cathedral, Wakefield became a city by Letters Patent dated 11 July 1888.

Wakefield Cathedral about 1900

At Bishop How’s enthronement, the Archbishop of York pointed out that the cathedral was inadequate for its new purpose and also urged the church people from across the diocese to support it financially. The first of his points was met when the extension to the east was completed in 1905 as a memorial to How. The second remained a perennial problem.

Planning for the cathedral extension began within two months of How’s death. An appeal was launched for £50,000, and John Loughborough Pearson, architect of the new cathedral at Truro, was commissioned to provide the designs, although the work was completed after his death under the direction of his son Frank. The slope of Kirkgate allowed Pearson to provide a crypt with a chapter house and vestries. The high-gothic scheme included lengthening the chancel, creating the Chapel of St Mark beyond it at the eastern end, and building north and south transepts. The foundation stone was laid by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Frederick Temple, on 18 June 1901. Work was soon to be suspended until further money was raised. Eventually £48,286 was subscribed and the extension was consecrated on St Mark’s Day, 25 April 1905.

The procession on 25 April 1905

The numerous niches on the outside of the vast east wall never held the figures for which they had been designed. The new chancel was consecrated on 27 December 1905.

The clerk of works was a Mr Crooks from Bristol Cathedral, and the main contractors were Armitage and Hodgson. The extension furnishings, including carpets from the East, were overseen by a ladies’ committee headed by the bishop’s wife, Constance Mary Eden. An altar cloth was worked by the Sisters of St Peter’s Convent. A monument to How in the form of a white marble tomb chest with a recumbent effigy by J. Nesfield Forsyth was placed in the south transept.

The memorial to Bishop How

Later memorials to the successive bishops and to some archdeacons have been placed within the extension. A memorial window to the diocese’s first registrar, William Francis Lovell Horne, who died in 1911, was added to St Mark’s Chapel.

Prior to the completion of the extension, Bishop Eden set up a committee to consider ‘the mutual relations of the diocesan and parochial authorities in Wakefield Cathedral’. A memorandum of 1905 focused on the lack of endowments, the adjustment of the legal position of cathedral and parish church, and the liabilities for the maintenance of the extension which could not ‘fairly be met by the parish only’. In a lecture in 1908 on the cathedral, William Donne claimed that the extension cost £110 a year to maintain but that there had not been much support from the diocese.

A Cathedral Management Committee was set up in 1910 under the chairmanship of the bishop, with equal representation from the cathedral and from the diocese

The Sanctuary was enhanced in 1912 by the addition of stone canopied sedilia and a credence on the south side with a bishop’s and chaplain’s seat opposite them. The bishop’s seat was flanked by the figures of St Paulinus and William Walsham How. Designed by Frank Loughborough Pearson and executed by Nathaniel Hitch, they were given as a memorial to the baronets Robert and Tristram Tempest of Tong Hall.

The Cathedral Sanctuary, Harriet Evans

It is thought that a great stone cross was erected towards the end of the tenth century close to the cathedral site, marking a preaching station. Such a cross was found in 1861 at a butcher’s shop in Westgate where, lying on its side, it was used as a doorstep. It was taken some years later to the Yorkshire Philosophical Society’s museum in York. In 1933 a replica of the cross was provided by Wakefield Historical Society and placed in the south transept.

Unlike the old cathedrals, Wakefield was and is a parish church as well as the mother church of the diocese. The Vicar of Wakefield had to serve as a parish priest, with attendant civic as well as pastoral responsibilities, but was also a significant figure at diocesan level. In the early years, both Norman Straton and his successor, William Donne, had the diocesan status of archdeacon. No subsequent vicars of Wakefield did. Under the Cathedrals Measures of 1931 and 1934, and an Order in Council of 1937, the Vicar of Wakefield gained the title of Provost, adopted at the time by the heads of all the new cathedrals, defining an office ‘which would be distinct from that usually associated with Crown patronage’.

Before the Reformation, the parish church had had a Lady Chapel, founded in 1322. When this was revived in 1935 it was fitted up with an altar provided as a memorial to Canon McLeod who had been the Vicar of Wakefield from 1919.

St Mark’s Chapel gained new features in 1943, making use of a bequest by Miss Margaret Percy Tew. The beaten-metal altar front and carved and gilded reredos were designed by Sir Charles Nicholson. The altar rails, again designed by Nicholson, were made by Robert Thompson of Kilburn and bear his trademark mouse.

A House for the Bishop

At the suggestion of Bishop William Boyd Carpenter, a separate fund was established in 1885 to provide a house for the bishop. Fund-raising was led by Carpenter’s wife who enlisted an impressive team of other women to canvass individual rural deaneries and run bazaars. By February 1888, a little over £10,000 had been raised. It was an open question as to whether a house would be bought or built. The purchase of Thornes House, Wakefield, was an early suggestion.

When Bishop How first came to Wakefield, he stayed at Thornhill Rectory, which had been made available to him by his old friend, Canon Brooke. He moved quite soon to a house in South Parade, Wakefield, rented from Michael Edwin Sanderson, later to be the diocese’s greatest benefactor. In 1889, he moved to Overthorpe, Thornhill. He found living in either Wakefield or Thornhill inconvenient as almost every journey across the diocese meant changing trains at Mirfield junction, described by his son as ‘the gloomiest and draughtiest of all stations’. How would have liked to live in Mirfield and a substantial property, Hall Croft, became a candidate but the Ecclesiastical Commissioners were anxious for the bishop to live nearer to, or in, his cathedral city. By 1890, a three-acre site had been acquired in the highly respectable St John’s area of Wakefield. William White, a colleague of George Gilbert Scott, was commissioned as the architect, and the foundation stone of the new brick Gothic ‘palace’ was laid on 24 October 1891. How moved into the mansion in 1893. The name Bishopgarth was chosen by the four men who had guaranteed to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners that a house would be provided. The term ‘garth’, derived from a Norse word for a yard and could mean an enclosure or a Manor House. The name was given to a hymn tune composed in 1897 for Queen Victoria’s jubilee by Arthur Sullivan to How’s words ‘O King of Kings whose reign of old hath been from everlasting’.

Bishopgarth

Bishopgarth was fitted with electric lighting in 1908, long before many of the parish churches.

Bishop How’s successor, George Rodney Eden, lived at Bishopgarth for some twenty years. However, in August 1918, he announced that high taxation and the high cost of living made it impossible for him to continue in residence there. It was immediately requisitioned by the Ministry of Pensions but was later let to the West Riding County Council. Eden moved to the Manor House at Heath where he remained for the rest of his period as bishop. A chapel was created there and, inter alia, was used for at least one confirmation service. James Seaton, Wakefield’s third bishop, lived at Heath for a short while but in April 1929 he declared his intention to move to Bishopgarth. He died there in 1938. As Archdeacon of Pontefract, Campbell Richard Hone had bought Woodthorpe Lodge with nine acres of grounds, a paddock, some woodland, a lawn and both flower and kitchen gardens. When he followed Seaton as Bishop of Wakefield in 1938, he insisted on remaining there. He described Bishopgarth as ‘a most inconvenient and badly planned house’, with ‘dark passages and small cubicle rooms for ordination candidates, a range of necessary rooms under the roof and awkward larders and kitchens’. His wife said that it was ‘quite impossible’ and that she could not manage it with all its inconveniences and the shortage of servants. Renamed Bishop’s Lodge, the house at Woodthorpe was bought by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. All subsequent bishops have lived there. Bishopgarth was sold to the West Riding County Council.

The Principal Administrative Bodies

In October 1888, Bishop How held a meeting of clergy and laity in the Wakefield Church Institute to establish the principal Diocesan societies: these were the Wakefield Diocesan Church Extension Society (which was to assist with funding both churches and parsonage houses), the Diocesan Board of Education (which was to contribute towards school buildings, teachers and the teacher training college at Ripon), and the Bishop of Wakefield’s Spiritual Aid Fund (for increasing stipends, providing visiting clergy during the sickness of an incumbent, helping to fund temporary rest for overworked clergy, and assisting infirm or aged clergy to retire). The Board of Education worked conjointly with the Ripon Diocesan Board of Education until January 1890.

An appeal was made at the October meeting (and many times subsequently) for donors to the funds who might give a single capital sum or promise an annual subscription. The initial subscription list was short and the sums promised, typically of the diocese, only modest. The donors could indicate which of the three funds they were supporting and it was soon clear that most regarded the Spiritual Aid Fund as the most important. In their first year the Church Extension Society received £742, the Board of Education £597, and the Spiritual Aid Society £3,650, including one donation of £1,000 earmarked for the parish of St Luke’s, Heckmondwike.

In May 1908, the different funds were brought together under the new umbrella of the Wakefield Diocesan Fund and the office of Organizing Secretary was established. A Diocesan Loan Fund was founded in 1911 to further assist church extension.

Wakefield Diocesan Church Organization Society was founded in 1894 as a limited company to hold trusts and land on behalf of the diocese. It became, inter alia, the trustee of parochial property used partly for religious and partly for secular purposes since this could not be vested in the minister and churchwardens but only in an incorporated body.

Bishop How held his first (and apparently only) synod on 29 April 1889. Some 250–300 clergy walked in procession, to the gaze of numerous bystanders, wearing their surplices, college hoods and caps, from the Church Institute in Marygate to the cathedral for a communion service led by How and the two Archdeacons. From the pulpit, How observed that he saw no need for the synod to meet either regularly or frequently. He referred to the importance of the laity in diocesan affairs. He spoke of the necessity, among the clergy, for personal holiness, pastoral activity, and their own daily prayer. He referred to the disputes over ritual then dividing the church, called for tolerance of the different positions and said that ‘there are but few now who rejoice in the spectacle of prosecution of ritual offenders’ although he added that, in his view, ritualism went against the spirit of loyalty to the church.

At the afternoon meeting in the Church Institute, How returned to the matter of the laity and spoke of having decided at the outset of his tenure to set up a Diocesan Conference. The Conference, presided over by the bishop, was to be the principal forum of the diocese and was to have no more than 460 members. Clerical members included the Archdeacons, Rural Deans, Proctors in Convocation, and all beneficed clergy. Unbeneficed clergy who had held the bishop’s licence as priests for two years, were also included. The Diocesan Chancellor and the Registrar were among the lay members, together with one representative from each parish, with a second from parishes with a population of over 4,500. Lay members were to be elected triennially in each parish by male communicants aged over twenty-one. The bishop could himself nominate ten people – clerical or lay – as members. The Conference was to elect a standing committee to be charged with its general business.

The first Conference was held on 22 and 23 October 1889, in the hall of Wakefield Mechanics Institute (popularly known as the Music Saloon although strictly the term applied only to its upper floor hall). The bishop spoke of the Conference aims to make the Church in the diocese as efficient as possible and to raise the ‘lofty standard of religion and of spiritual life among the people’. A committee was appointed to draw up a scheme for the Diocesan Board of Education which would be needed in January 1890 when the new diocese became independent of the Ripon Board.

Throughout the period under consideration and indeed until it was replaced in 1971 by Synodical government, the Conference normally took place annually over two days in October, meeting in various halls and churches across the diocese. It received reports from all diocesan organizations and heard papers on key issues affecting the Church nationally or at diocesan level.

The Conference also passed resolutions on many issues, including pending parliamentary action. Early in its life, for example, there was a special meeting in April 1883 to debate a motion opposing the Welsh Suspensory Bill which was to disestablish the Church in Wales. Education was a major and perennial issue in the first decades of the diocese. In 1908, at the time of an Education Bill aimed at reversing some of the provisions of the 1870 Education Act, the Conference placed on record its ‘deliberate conviction that there is no hope of any arrangement of the Education Question affording any permanent settlement or lasting peace, which does not secure – as far as it is possible to secure it – the opportunity of full church teaching for all children whose parents desire it, given by qualified teachers who are themselves members of the Church’.

From time to time the Conference focused, too, on social questions. The 1907 Conference, for example, heard a paper on housing reform (a matter in which Bishop Eden was especially interested) by Canon Moore Ede of Gateshead, who referred to the value of town planning, to co-operative house building on lines known as Tenants Limited, and to garden cities. In 1923, the Conference focused on birth control and the instruction of the young in the ‘laws’ of sex.

Licensed but unbeneficed priests living at the Community of the Resurrection in Mirfield were included in the membership of the Conference. This brought it one of the best minds in the Church at the time, Walter Howard Frere (1863–1938), an outstanding liturgical scholar who had been one of the six original members of the Community and who was the Superior at Mirfield in 1902–13 and 1916–22.

Changes in the diocesan organization reflected those at national level. Prompted, it seems, by the great Pan-Anglican Congress of 1908, the two Archbishops set up a committee to look into the organization and financing of the churches. In the light of the committee’s recommendations, the financial organization of the Wakefield Diocese was reshaped. Canon Richard Phipps, who had come to Wakefield as a curate at the cathedral in 1892, resigned the living of Brighouse in 1912 to become the Wakefield Diocesan Secretary, and, in anticipation of the national scheme, he masterminded a restructuring of the financial organizations of the diocese. Under his guidance, and after agreement at the 1912 Diocesan Conference, the over-arching Wakefield Diocesan Board of Finance was established, to take control from 1 January 1914, of the Wakefield Diocesan Education Society and the Wakefield Diocesan Fund (which held both the Wakefield Church Extension Fund and the Spiritual Aid Fund). From then onwards, the Conference, which was the supreme authority in matters of finance, had responsibility for determining the sum needed each year for diocesan expenditure.

The new scheme set out seven areas of church work and the diocesan bodies which would come under each:

Training for the ministry

Ordination Candidates’ Fund.

Maintenance of the ministry, clerical and lay

The Bishop of Wakefield’s Spiritual Aid Society.

The Wakefield Church Extension Society (object iii).

Provision of pensions for the ministry

The Wakefield Clergy Pensions Fund.

Provision for widows and orphans of the clergy and for necessitous clergy

The West Riding Charitable Society Ripon and Wakefield section.

The Queen Victoria Clergy Fund.

(Neither of these was strictly diocesan but could be used by the Board of Finance as distributing agencies.)

The erection of church buildings

The Wakefield Church Extension Society.

The Wakefield Diocesan Loan Fund.

The Cathedral Sustentation Fund.

Religious education of the young

The Wakefield Diocesan Education Society.

The Diocesan Association of Church Schools.

The Wakefield Diocesan Sunday Schools Association.

Provision for expenses of diocesan and central organizations

General Purposes Fund.

The Conference had the responsibility of appointing the Board of Finance.

Until 1912, giving by parishes towards the expenses of diocesan administration was entirely random (or so it seems). The sums contributed were very widely varied depending in part, but in part only, on the size and affluence of the parish. In 1911, the smallest sum contributed, 19s 4d, came from Farnley Tyas. The parish of Dewsbury gave £58. At the 1911 Diocesan Conference the scheme for quota payments was introduced, with parishes being assessed against a variety of criteria and then informed of the size of contribution required in the following year ‘to meet the diocesan and central needs of the church’. Free-will offering schemes were strongly recommended. The system was, inevitably, widely resented albeit utterly essential. In 1930 a report was made to the parochial church council of Holy Trinity, Wakefield, observing that Holy Trinity had always considered the payment of the quota as its first duty. The note adds the wry observation that it was ‘almost alone’ in the diocese in taking this view initially.

In 1913, Phipps, who had private means, moved into Manygates House, Sandal, a substantial dwelling lying in some six acres of parkland and ‘pleasure grounds’. In the absence at the time of any other diocesan administrative base, the house became the centre for meetings of the Diocesan Board of Finance and other committees.

Diocesan conferences gained a place in the national administrative structure in 1920 when the Church Assembly was established after the seminal report of 1916, Church and State, had argued that Parliament had ‘neither the leisure, fitness nor inclination to perform efficiently the functions of ecclesiastical legislature’. The Assembly was made up of a House of Bishops, a House of Clergy and a House of Laity. Under the Church Assembly (Powers) Act of 1919 it could pass measures which, if approved by Parliament, received Royal assent, just as Acts of Parliament would do, and became part of the statute law of England. Effectively the state church gained a high degree of self-government. Diocesan conferences elected their representatives to serve for three-year periods in the House of Laity. Parochial Church Councils and the attendant Electoral Rolls became mandatory. The number of parochial representatives on the Diocesan Conference depended from 1921 on the size of the electoral roll rather than on the number of communicants.

The Diocesan Board of Patronage was established in 1920. The Diocesan Dilapidations Board came into being in November 1923 under the new Church Assembly’s Ecclesiastical Dilapidations Measure of that year. Its concern was with the state of repair and the maintenance of parsonage houses. It had to appoint surveyors, and any further alteration to the houses could be made only with the Board’s consent. It was accepted that the Board might itself have to instigate repairs and would then need to recover costs.

The diocese had perhaps no permanent office until 1923 when it made use of 5a South Parade, although certainly for a time in the 1890s its administrative headquarters was in Manor House Yard, close to the cathedral. Then, in 1925, through the gift of Miss Mary Thompson, it acquired 1 South Parade which was given the name of Church House. The house was both opened and dedicated, by Bishop Eden, on 4 November.

There were very few synods. The first since the time of Bishop How was held on 10 and 11 May 1921, when Bishop Eden expressed concern at the comparatively small number of candidates from the diocese coming forward for ordination, and went over the resolutions from the Lambeth Conference and York Convocation.

Church House

Other Diocesan Organizations

Bishop How established a Diocesan Lay Readers Association (for men only) in 1889. Anyone with a licence from Ripon would be granted his licence. Others could get one, it was announced, by passing a simple examination on the Bible and the prayer book and by satisfying the bishop as to his moral character and fitness for the office. All Lay Readers would get a licence which would hold good throughout the diocese and, if an incumbent requested it, would also be given a commission to exercise the office in a particular parish. Perhaps it should be noted that, although ‘Reader’ has always been the formal designation, until recent years ‘Lay Reader’ was much more commonly used within the diocese, even in issues of the Diocesan Gazette and the Wakefield Diocesan News. For the sake of consistency, ‘Reader’ has been adopted hereafter.

The Diocesan Council of Girls’ Friendly Societies was established in 1891 by Edith How, the bishop’s daughter-in-law, who came with her husband to live at Bishopgarth with the widowed bishop.

A Diocesan Board of Missions was formed in 1905. It was designed to promote the work within the diocese to support missionary work abroad and, to this end, to plan missionary exhibitions and festivals within the diocese.

The Diocesan Sunday School Teachers’ Association was founded on 27 June 1908, bringing together a number of smaller bodies.

Bishop Eden formed the Diocesan Board of Readers in 1921. At the time he explained, ‘In the increasing scarcity of clergy, we are convinced that a real call is coming, especially to our educated laymen, for all earnest and sincere church people to take an active part in the evangelistic work of the church.’ The aim of the Board was to raise standards and to arrange and supervise conferences. A first diocesan admission service for Readers was held at the cathedral on 6 May 1922. Sixty-six Readers were admitted into the new office. Each attended in the Chapter House to sign a new roll and make a declaration. They were presented by Archdeacon Harvey as the Warden of Readers. W. H. Coles served as the registrar for the new organization. Bishop Eden said that the service marked an epoch in the long and chequered history of the Readers’ movement which had been revived in the 1870s. Formerly it was only a diocesan office. Now Readers were admitted into a Corporate Body for the whole Church of England.

In 1930, Bishop Seaton formed a Diocesan Council of Youth.

New Churches, New Mission Rooms and New Parishes

The fundamental concerns of the diocese in its first fifty years were the provision of further churches to serve a growing population and the clergy to staff them, and the gathering of the flocks to attend them. Pressures for new churches came from the spread of housing into the suburbs, the emergence of council-housing estates, and the development of a new community serving a colliery. The churches might be built for new parishes, or in areas designated as conventional districts which might later become independent parishes, or chapels of ease (consecrated buildings in the same parish as, but at a distance from, a parish church) or as mission churches (licensed for worship but not consecrated). Where there was little hope of finance for a church building, Commissioners looking at the needs of the diocese advocated the opening of mission rooms.

Not infrequently, new congregations were brought together in these mission rooms, perhaps making use of an existing church school. A temporary mission chapel might follow. As funds slowly accumulated (or if a prosperous benefactor emerged) a permanent church might ensue. The lack of money, in particular, meant that the fulfilment of new-church schemes might take a long time, as much as twenty years or more.

While the landed classes had been generous in building and endowing churches in the area in the past, the new diocese now enjoyed relatively little of their support. Some still gave sites for new churches (Lord Dartmouth, for example, provided the site for St Andrew’s at Bruntcliffe) but these might come, too, from industrial concerns or from a local authority which had acquired land for housing.

The process of church building and of establishing new parishes had continued independently of the expectation of a new diocese so that Bishop How’s earliest act of consecration, on 27 May 1889, was of one of the churches planned before the see was created. St Luke’s, Heckmondwike, was on a site given by the Low Moor Iron Company. The parish had been formed in 1878. Services had taken place first at the National School and then in a temporary iron church. Typically for the period the church was designed (by Medland Taylor of Manchester) in a Gothic style, specified at the time as ‘geometrical decorated’. An endowment had been provided by Mrs Woodhead of Moor House.

Lack of funding meant that a church might be partially completed years before the overall design was accomplished. An example of the not unusual struggle was the forty-year gestation of St Peter’s, Barnsley. Its history went back to 1872 when a schoolroom was built on Doncaster Road as a mission for St Mary’s, Barnsley’s parish church. Two years later a visiting priest conducted a mission in the vicinity which resulted in the drawing together of a congregation. One of St Mary’s curates, John Lloyd Brereton, was given charge. Plans for a church were drawn up by the Hampstead architect Temple Lushington Moore (1856–1920), but fund-raising was dismally slow. By 1883, a large enough endowment had been amassed to provide a stipend of £150 a year and the new parish was formed with Brereton as its first vicar. Three years later, in 1886, a temporary nave was built on the site planned for the church, next to the schoolroom. By 1892, a more extensive and permanent building could be envisaged and the cornerstone was laid in January of that year. At the time, Brereton referred to the ‘slow and uphill struggle’ and observed that when he had first gone there, the local people had little idea of what a church was and thought it was something for the upper classes. In October 1993, Bishop How consecrated the still-temporary nave and the newly added chancel, side aisles and vestries. With the church still unfinished in 1908, a public meeting was held in Barnsley’s Arcade Hall when the Rector of Barnsley, Canon Foxley Norris, said that the parish still had only half a church and no parsonage house and that out of a stipend of £160 the vicar was spending £40–£50 on rented accommodation. A committee was established with representatives from the church councils of each of the Barnsley parishes to remedy the situation. The foundation stone of the new nave was laid on 2 July 1910 and the completed church was consecrated on 14 December 1911.

Each of Wakefield’s first three bishops set up a Commission of Enquiry into the ‘wants and requirements’ of the diocese, How in January 1889 within a year of his installation, Eden in 1907 when he had already been in the diocese for nine years by which time many of the proposals of How’s Commission had been met, and Seaton in 1929 when, with a somewhat changed brief, the Commission was asked to report on cases where existing churches and mission rooms appeared to be unnecessary.

How’s Commission included both his archdeacons, all six rural deans, a further member of clergy from each of the deaneries, and a number of lay people. It considered not only the need for more churches but the situation in regard to church schools, and the question of whether there were advowsons which could be transferred to the bishop. Its report, which was published in March 1890, noted that it was always difficult to secure the endowments required for new parishes and that the funds at the disposal of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners to contribute to them had been seriously diminished. Hence the Report, published on 5 March 1890, recommended the formation of only a modest number of new parishes. Two further parishes were needed in the Dewsbury Deanery, where steps had already been taken to create one at Bruntcliife, to serve Purlwell, and Gawthorpe with Chickenley Heath. In the Halifax Deanery they were needed to serve a rapidly developing suburb in the Queen’s Road area, and in the centre of Todmorden. Both Marsh and Crosland Moor, in the Huddersfield Deanery, warranted new parishes. St Jude’s, a newly built chapel of ease at Salterhebble, which was almost ready for consecration, might also serve a new parish. Adjustments were suggested to the boundaries of other parishes and the Report recommended the creation within existing parishes of further chapels of ease, mission churches and mission rooms. A new parish of Horbury Junction had been formed, with services held in a mission room, but a new church was needed.

Bishop How, in a rather low-key manner, issued an appeal for £50,000 to meet the recommendations in the Report. Typically it met only a modest response. In its first year it raised £13,670 but by the time of the 1898 conference it had realized only £27,000. It was wound up the following year.

Very gradually most of the recommendations were met. St Jude’s was consecrated on 30 November 1890 and the area became a district chapelry in January 1891. The church of St Mary the Virgin, Horbury Junction, the third Anglican church in the village of Horbury, was consecrated on 10 October 1893. The new parish of Crosland Moor was established by Order in Council in 1893 after Sir Joseph Crosland offered £1,000 towards building the church. Bishop How did not live to see the church itself, however. The memorial stone for St Barnabas was laid by Bishop Eden on 4 August 1900. The church was consecrated on 4 October 1902. (Its west end was completed, although without its planned tower, in 1958.)

Before his death in 1897, Bishop How had licensed or consecrated more than twenty chapels of ease, mission churches or mission rooms. Some were merely rooms within a church school, as at Northowram, some were temporary iron churches erected cheaply in the hope that, in due course, a new church would be built and possibly a new parish established, and some were handsome daughter churches like St Aidan’s, Skelmanthorpe. This had been designed by George Frederick Bodley (1827–1907) for the parish of Scissett. It was consecrated on 28 September 1895 and became a separate parish in 1900. The last church that How consecrated, in 1896, was St Saviour’s, Heckmondwike, which was provided by Edward Wheatley-Balme as a chapel of ease, and which replaced an iron church. Iron churches, popular and cheap, were eminently capable of recycling. This one had come from St Luke’s Cleckheaton in 1889 and went on to Jeremy Lane, Heckmondwike, for use as a Sunday School room.

One of How’s last acts was to agree with Edward Simpson of Walton Hall the site for St Paul’s mission church in Walton. It was another iron building and had been constructed in London and brought in sections by rail to Walton. It was dedicated on 10 January 1898 by Bishop Eden.

In August 1900, Lord Savile laid the memorial stone of All Saints, the chapel of ease at Elland. It was the new peer’s first visit to the diocese since he had acceded to the title, and a formal address of welcome was given. The architect was E. H. Fellowes Prynne but the intention, not unusually, was to build just the chancel, with vestries below it, and the first part of the nave. The north and south transepts would follow when finances permitted. For a time in 1903 work came to a standstill because of lack of money but in November 1903 the chancel and transepts were dedicated by Archdeacon Brooke. A debt of £5,000 meant that there could be no consecration. When consecration came, in May 1912, the church was spoken of as ‘a noble ideal pursued with faith and tenacity, through almost unspeakable difficulties’.

In the Halifax Deanery, a separate scheme for church extension in the town and district was inaugurated at a meeting on 6 November 1900. Its objects were to obtain sites, build and enlarge churches and mission churches, and make grants towards the stipends of additional clergy. It was accepted that in regard to the last item it would co-operate with the Diocesan Spiritual Aid Society. In consequence, in 1902, the Halifax and Rural Deanery Church Extension Society was formed and proposed the creation of a new parish carved out of King Cross and Mount Pellon (already mooted by How’s Commissioners), a new parish near Brighouse Station carved out of the parish of Rastrick, and a stone church to replace the iron one at Siddal. It identified the need for mission rooms at Bailiff Bridge, Norwood Green, Hove Edge, Wainstalls, Luddendenfoot and Midgley.

In some few places, new churches were provided without struggle by individual benefactors. How’s Commissioners’ Report had noted the desire for a mission church at Cornholme, Harley Wood, at the north-western end of the diocese. An iron chapel opened there in 1896. The handsome stone church of St Michael and All Angels, which replaced it, designed by C. Hodgson Fowler, was consecrated on 27 September 1902, the full cost being borne by Mrs A. Master-Whitaker, wife of the Vicar of Helme, who secured an endowment of £120 to provide for a Curate in Charge. Cornholme became a district chapelry a year later.

At Thurlstone, in the geographically vast parish of Penistone which covered thirty-four square miles and had a population of over nine thousand living in scattered hamlets, a chapel of ease was, the Commissioners had said, ‘much needed’. It had to await benefactors. The sisters Mary and Hannah Bray, who died in 1895 and 1897, left the residue of their estates in trust to the Vicar of Penistone and the Bishop of Wakefield (in all some £5,000) towards it. Captain Vernon Wentworth of Stainborough Hall (Wentworth Castle) made a grant towards the provision of a Curate in Charge. St Saviour’s was another of the churches designed by C. Hodgson Fowler. Its foundation stone was laid on 5 November 1904. The church was consecrated on 9 December 1905. Fowler’s plan had been for a tower at the west end of the church. However, this was never built and the west end was ‘temporarily’ completed (it still is) with a brick wall where the rest of the church is in the local millstone grit.

St Saviour’s, Thurlstone

If St Peter’s, Barnsley, took many years to complete, the church of St Edward the Confessor, serving the Kingstone area at the western end of the town, was, as it were, handed to the diocese on a plate. It came quite independently of any recommendation by How’s Commission. It was surely the most sumptuous of the new churches in the diocese, and was built and endowed by Edward Lancaster of Keresforth Hall in memory of his parents. Early English in style, it was modelled on a church in Southport designed by same architect, Goodwin S. Packer. The memorial stone was laid by Lancaster’s daughter, Mrs Fanny Jane Shaw, on 5 October 1900, and the completed building was dedicated and consecrated by Bishop Eden on 13 November 1902. The church, which had a clerestory, side aisles and a mosaic-floored chancel, was designed to seat 400, with a large crypt containing a meeting room with stage, and a vestry with a robing room. Another ground-floor vestry was converted into a Lady Chapel in 1910. No expense was spared on the materials. It had granite columns, pews of pitch pine, choir stalls of oak, an octagonal alabaster pulpit and matching octagonal font by Norbury, Paterson and Co. of Liverpool. There was a reredos in English alabaster and Italian marble by Harry Henry and Son, Exeter. Lancaster also provided a seven-bedroom vicarage. A good deal of house-building was taking place in the area and a new parish was formed from parts of St George’s and St John’s.

Neither of the new parishes proposed at Purlwell and the Queen’s Road area of Halifax had come into being when, after nine years as its bishop, Eden commissioned a new report in 1907 on the needs of the diocese. In the period since Bishop How’s Commission had reported, the diocese had gained three ‘fully equipped’ parishes, five chapels of ease, and twenty-one mission churches and mission rooms. There had also been an increase in the number of curates and Readers. Among the mission churches was St Hilda’s, King Cross, which had been opened in 1898 as a memorial to Bishop How. In 1909 Eden’s Commissioners recommended this as the church for the previously suggested parish in the Queen’s Road area. The need for a parish at Purlwell was also reiterated. But otherwise, rather than proposing further new parishes, the Report advised that ‘at least’ three conventional districts – lying within an existing parish but with their own Curates in Charge – should be formed. These were needed where a colliery or mill had developed its own population. In due course they might become separate parishes. The Report looked for the completion of three partially built churches and the provision of nine parsonage houses, including one for each of the two new parishes and others for parishes where no parsonage had yet been built or to replace an existing but insanitary house. It urged that steps should be taken towards the erection of four more chapels of ease, ten mission churches (six of them taking the place of existing mission rooms) and twenty-three new mission rooms. One parish was to be taken back into the parish from which it had been divided. Three existing parish churches, which were now too small for an expanding population, should be replaced by new churches. The report also recommended some rearrangement of parish boundaries and some rearrangement of parishes within rural deaneries. It noted that the present supply of clergy was totally inadequate and that fifty-seven parishes needed further staff. A body of special-service clergy was needed, too, for hospitals and other public institutions. The Report was of course followed by an appeal for the money, this time with a rather greater fanfare!

How’s appeal for funds to meet the recommendations of his Report had been launched quietly. Not so Bishop Eden’s! Randall Davidson, the Archbishop of Canterbury, came to Wakefield in the summer of 1910 to initiate it. He stayed at Bishopgarth overnight before being given a civic welcome in the Council Chamber of Wakefield Town Hall on the morning of 25 June. A public lunch for 500 people, with a menu described by the Wakefield Herald as ‘recherché’, took place on the ground floor of the Corn Exchange before the company moved upstairs to the assembly room for the formal speeches. The event, possibly the last such occasion in the diocese, was attended by many of the leading aristocracy and gentry from the county. They included Earl Fitzwilliam, the Earls of Dartmouth, Harewood and Scarborough, Lord Allendale, Lord Savile, Lord St Oswald, Sir George Armytage, Sir Edward Green, Sir Thomas Pilkington, Sir John Ramsden, Sir Walter Stanhope, and the Right Honourable Charles George Milnes Gaskell. Davidson referred to a link between himself and Wakefield when he spoke of a predecessor, Archbishop Potter, who had been a Wakefield man, and remarked that he had a portrait at Lambeth Palace of Potter as a boy of eight evidently reading from a Greek Testament. Bishop Eden spoke of the need to raise some £6,500 a year – more than twice the current level of donations – to provide a further £3,000 for the Spiritual Aid Fund, £1,500 for the Church Extension Fund, and £2,000 towards Education.

Among the parish churches that Eden’s Commissioners identified as too small was St Paul’s at King Cross, Halifax. The parish had been taken from the parish of Halifax in 1846 and the church had been consecrated in 1847. Although parts of the parish had been taken into St Hilda’s and St Jude’s, it still had some 15,000 or 16,000 inhabitants. The original church seated 450. Its replacement, on a nearby site, was designed by Sir Charles Nicholson and was his first major commission in the diocese. The new St Paul’s was consecrated on 26 October 1912.

When Bishop Eden consecrated St Matthew’s, Northowram, on 31 May 1913, he noted that it was the third church in the Borough of Halifax that he had consecrated in three years. Hitherto, the old school had served as a mission church. The church was the gift of George Watkinson (d.1961) who had been the curate at Coley but who became the first vicar of the new parish. The cost of the tower was defrayed by his brother, S. L. Watkinson. The architects were Walsh and Nicholson of Halifax and the style was described as ‘Halifax vernacular’ or fifteenth-century English Gothic, and subsequently as ‘Arts and Crafts Gothic’. The nave and aisles were lined with diamond-shaped brown quarry tiles from Nostell. The site had been a quarry.

The war and the ensuing depression led to a period of stagnation before further churches were built. By 1924, shortly before its major expansion, the diocese had 177 parishes (those worked in plurality counting as one). Ten had a population of over 10,000 while, at the other end of the scale, fourteen had a population of under 1,000, Wilshaw being the smallest at 232.

New house-building programmes prompted the building of St Cuthbert’s, Birkby, in 1925, with the intention of creating the first new parish in the diocese for many years. The architect was A. H. Hoare who, more than a decade earlier, had designed St Andrew’s, Purlwell. The foundation stone was laid by Lord Halifax on 2 May of a church which would initially have just a chancel, a part of the nave, and part of the south aisle. The partially built church, with a temporary west end, was consecrated on 23 August 1926 and the area, until then a conventional district, became a separate parish in 1933. (The west end was completed in 1956.)

Local authority building schemes, providing substantial housing estates, brought a new challenge to the diocese. Wakefield Corporation embarked on its great Lupset estate in the early 1920s. A three-acre site was given by the vendors of the Snapethorpe estate, the Old Roundwood Colliery Company, and earmarked in 1926 for an Anglican church (Methodist and Roman Catholic churches were also built to serve the estate) and an appeal was launched for funds in May 1928 when the area had 1,400 new houses and a population of over 7,000. Initially only a parish hall-cum-mission room was built. The church itself, in a modern style breaking away from the Gothic, was built from stone from a demolished woollen mill and from the old Wakefield Registry of Deeds building in Kirkgate. When it was consecrated, in October 1936, it was the first church to be consecrated in the Borough of Wakefield for sixty years. The new parish was formed from parts of Alverthorpe, St Michael’s and Thornes.

Meanwhile, Bishop Eden retired in October 1928. He had consecrated two last churches in the preceding June, St John the Divine, Rishworth, and St John the Evangelist, Staincross. The latter, which then gained its own parish, had been built as a chapel of ease for Darton, and Bishop How had dedicated its chancel on 27 April 1897.

The first consecration by Eden’s successor, Bishop James Seaton, on 20 March 1929, was of St Michael’s Castleford, in the area which had come into the diocese only in 1926.

When Seaton set up a Commission, on 9 August 1929, to inquire into the needs of the diocese, the emphasis was different from the two earlier ones, reflecting the changed times. In addition to looking at further church extension, it was to report on cases where existing churches and mission rooms appeared to be unnecessary. It was, as the previous Commissions had done, to advise on possible rearrangements of parish boundaries and rural deaneries, but it was also to enquire where paid lay workers might be usefully employed. It completed its report in two years. It noted that since Eden’s 1909 report, eleven new parishes and two new ecclesiastical districts had been formed. Nine new parish churches had been built and consecrated and there had been four new district churches, and eight mission churches or mission rooms. There were three instances of the union of parishes. Twenty-four new vicarage houses had been built or bought.

In 1932, despite the difficult economic climate nationally, Bishop Seaton made an appeal for £35,000 – the report had suggested a figure of £45,000 – to fulfil the new recommendations. In less than three years, on 6 April 1935, he was able to hold a service in the cathedral celebrating the realization of that sum. ‘No appeal in this diocese’, Seaton claimed, ‘has been ever supported by so many individuals, rich and poor, young and old.’ Others attributed its success to Seaton’s friendly personality and ready availability. Many organizations, like the Mothers’ Union, the Girls’ Friendly Society, and the Church Lads’ Brigade, as well as parishes and individuals, had contributed. Addressing the congregation, Seaton outlined what had already been achieved. Holy Cross at Airedale had been consecrated. Building had begun at St George’s, Lupset. St Barnabas, Barnsley had been completed. An iron church, transferred from Pontefract, had been sited at Three Lane Ends, Castleford (and dedicated as St James the Great) as a mission chapel for All Saints, Whitwood Mere (Hightown). It was prompted by changes to the parish boundary and plans by Castleford Urban District Council for a housing estate. There were ‘school churches’ at Lundwood and Wrangbrook, a mission building had been acquired at Rawsthorne, endowments had been provided for six curates, and five further sites had been obtained for church or school building.

The village of Upton had developed as a consequence of the opening of the colliery there. The colliery company provided a site for the church cum schoolroom at Wrangbrook in the parish of South Kirkby. Colonel Sir Maurice Bell, one of the directors of the company, laid the foundation stone of a new, small and modern church building on 4 May 1931. It was dedicated to St Michael.

The building of the vast Airedale estate by Castleford Council brought an urgent need for a new church there. The township had come into existence in 1921. A temporary iron church had been acquired from Castleford in 1922 when the area was still in the Diocese of York. Initially a conventional district, with a Curate in Charge, it became the separate parish of Airedale with Fryston in 1930. Appealing for funds for a permanent church, Bishop Seaton called it ‘the most immediately urgent need in the diocese’ and urged all those who bought Airedale coal to make a donation. The building of the church of the Holy Cross was remarkable! News that Fryston Hall was to be demolished prompted the purchase of its stone for £300. The stone was taken to the site for the new church with the help of volunteer labour, including that of coal miners. The Ionic columns were re-erected at the front of the church. The Marquess of Crewe laid the foundation stone on 18 March 1933 and the church was consecrated on 14 July 1934. The church was designed by Sir Charles Nicholson and the pews were by the ‘mouse man’, Robert Thompson of Kilburn. Many parishioners had come to Airedale from County Durham and the stoup was made of stone from Durham Cathedral.

John Charles Sydney Daly, the energetic young man who had come to Airedale as Curate in Charge in 1929, moved on less than a year after the consecration of the church. He was consecrated as the first Bishop of Gambia and Rio Pongas on the Festival of Philip and James, 1 May 1935, at All Hallows by the Tower, London. Daly had been at King’s College, Cambridge and the Dean of the College preached on the occasion. Fifty people from Airedale attended. ‘All must have felt that they were taking part in a gallant adventure of the Church of England,’ the Dean observed.

The offertory at the 1935 service of thanksgiving for the success of Seaton’s appeal was for the Gambia Diocese.

Holy Cross, Airedale

The Union of Benefices

Rationalizing by uniting benefices has occurred since the sixteenth century. While the spate of unions of benefices in the diocese did not come until the latter part of the twentieth century, some few unions actually took place or were explored much earlier. The union was normally preceded by a Commission of Inquiry and required an Order in Council to confirm it. In rural areas, benefices might be united where the population was too small to warrant the maintenance of separate parishes. In urban areas, already in the 1920s the clearance of housing from town centres might provide a case for uniting adjacent benefices. Under the Union of Benefices Act of 1921, St Mark’s, Huddersfield, was united in 1922 with the mother parish of St Peter, and St Luke’s, Norland, was united with Christ Church, Sowerby Bridge. In 1924, having been overseen by the Vicar of Penistone for at least fifty years, the benefices of Midhope and Penistone were united.

Bishop Seaton promoted a Public Inquiry in the mid 1930s, during the building of the Lupset housing estate, into the advisability of uniting Christ Church, Thornes, with St James’s, Thornes, in Wakefield. The scheme was rejected at the time but Seaton warned that the removal of much of the population of Christ Church (through slum clearance) would mean that the possibility must be revisited.

The Two Religious Communities: the Community of St Peter, Horbury, and the Community of the Resurrection

Although the Community of St Peter, Horbury, and the Community of the Resurrection at Mirfield lie within the diocese, neither is a diocesan body. But their contribution to the work of the diocese warrants their place in this history.

The Community of St Peter, the first religious community in the north of England since the Reformation, was founded in 1858 by the high-church incumbent of Horbury, John Sharp. He had been prompted by his cousin, Harriet Louisa Farrer, to bring together women ‘pledged to devote themselves to rescue and preventive work’, who could run a refuge for girls and young women. More will be said of this long-lasting venture later. As the Community grew, Sisters were sent, or daughter-houses founded, to oversee penitentiaries or rescue houses elsewhere, including Carlisle, Chester, Croydon, Freiston in Lincolnshire, Joppa (Edinburgh), Leeds, London, Rushholme (Manchester), Sheffield, and Wolverhampton. Some of their number also worked in more local parishes of high-church inclinations, visiting and teaching. They served in all three Horbury parishes, at Middlestown, and as far afield as South Elmsall, and All Saints, Leeds. At Horbury Bridge, as well as teaching in the Sunday School, they managed a night school for girls. In the early 1920s they also assisted with parish work at two London churches and at St Peter’s, Folkestone. From 1925, invited by the parochial church council, the cathedral staff included two of St Peter’s nuns. They lived in Wakefield at St Gabriel’s House, Rishworth Street, which was dedicated on Lady Day, 25 March. At the cathedral they cared for the altar vessels and the vestments, cleaned the silver, looked after the linen and arranged the flowers. But they also worked with young people in the Sunday Schools and undertook pastoral work in the parish. Between 1900 and 1908, when it ceased to hold women prisoners, nuns from St Peter’s served as visitors at Wakefield Prison. From 1922 they also visited Armley Gaol. In 1900–20, Sisters managed the County Home, Stafford, for discharged women prisoners. The Community of the Holy Paraclete at Sneaton Hall, Whitby, was founded from St Peter’s where a small school, later to be called St Hilda’s, had been started in 1875. Shortly after the outbreak of the First World War, the school was refounded at Whitby by some of the Sisters from Horbury who had taught there and who formed the nucleus of the new Order. During 1905–30 Sisters managed a High School and undertook missionary work at Nassau in the Bahamas.

Retreats for clergy, for their own Associates, and for others, were provided at the Convent from 1865. In 1915, they began offering retreats to working women and girls. In the 1920s they provided a retreat house at Balhousie Castle, Perth.