Читать книгу Wakefield Diocese - Kate Taylor - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

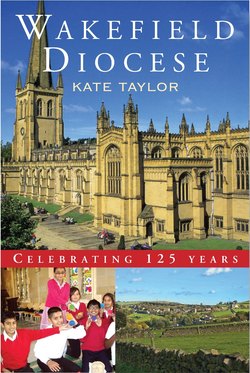

ОглавлениеIntroduction

The 125 years since the Diocese of Wakefield was formed have seen immense changes both within the Established Church and within society. They have seen two world wars, a proliferation of faiths (in particular of Islam within the diocese), a decline in people coming forward for ordination, a radical change in the status of women within the Church, and an accelerating decline in church-going. The Church has moved from being relatively inward looking to a position where community involvement of many kinds has become something of an imperative. Among the many remarkable changes it is worth noting that a suggestion in 1907 for intercessions ‘to stay the advance of Moslem activity and its false teaching by the missionary zeal of the Church’ would have been wholly unacceptable as an official recommendation a hundred years later.

There has been a substantial increase in mission focus. Before the Second World War, churches devoted considerable time and money in efforts to support the various missionary societies which undertook work overseas. In 1981 Bishop Colin James remarked, ‘Not so long ago we used to think of mission as something we in the west did to others in foreign parts. Then we awoke to the need of mission in de-Christianized England too.’

Writing at the time of the ninetieth anniversary of the founding of the diocese, John Lister, Provost of Wakefield Cathedral, said that its history had seen ‘a complete revolution in thought and social patterns’.

The first fifty years of the diocese saw a steady drive towards the provision of more churches – some with their own new parishes – and mission rooms. They also saw the struggle to retain church schools and press the claims of religious education. Later years have seen considerable retrenchment with the union of benefices, the creation of team parishes and group ministries, and the redundancy of no small number of church buildings.

In 1973, Eric Treacy, Bishop of Wakefield since 1968, looked back on forty years in the ministry to identify some of the changes he had seen in that comparatively short period. In 1933, the majority of clergy were from public schools and the ancient universities, he said. The Church was unselfcritical and, he argued, only a little sensitive to issues of human welfare. There had been an ‘astonishing change’ in the relationships between the different Christian denominations, and prejudice had gone. There had, even forty years earlier, been a lack of understanding between the Catholic and Evangelical wings of the Established Church itself. Now he found mutual respect. In the 1930s there was still an earnest desire to convert the heathen in foreign parts. Forty years later there was an acceptance of peaceful co-existence with the ‘other great religions’, though Treacy regretted that this had robbed missionary work of some of its dynamic. He discerned a change, too, in the relationships between bishops and their clergy. Bishops had been remote figures, ‘inaccessible and often incomprehensible’. Motor cars and telephones, he thought, had been among the catalysts for change. In the 1970s bishops had become ‘everybody’s men’. They were to be ‘grabbed’ for every kind of occasion, perhaps because of the lack of other public figures to take a place on platforms. But in the 1970s he also found the Church in flux. ‘Forty years ago men were ordained to a Church which was stable, which had a well-established place in the life of the community,’ he said. And went on, ‘Men who seek ordination today are entering the ministry of a church in which nothing is certain, which is far from well-established, in which things are constantly changing. They give themselves to the service of a Body which offers less security than almost any other field of employment.’ In his Memoir, written in 1955, Wakefield’s fourth bishop, Campbell Richard Hone, spoke of the problems he encountered in the 1940s when the majority of candidates for ordination were ‘from lower middle-class homes, good and sincere for the most part but with little evidence of outstanding ability, or theological knowledge’.

The 125 years saw a gradual but marked change in the role of lay people in the Church nationally which was reflected in the diocese. This has included the introduction of lay ministers and the emergence from parish laity of those seeking ordination as self-supporting priests. Recent years have seen, too, a broader embrace of cultural forms, in particular wider styles of music, and art (including art installations), and a widening of cultural and social concerns.

The major problems facing the diocese at the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first were those facing the Church nationally: declining congregations except (perhaps) in evangelical churches, the lack of clergy and certainly the lack of money to pay them, the refusal of some Anglo-Catholic parishes to accept women priests and their insistence on having a separate bishop, a diminishing liberal influence and the difficulty and reluctance of some parishes to pay the parish share.

On a much more positive note, many churches which were once open only on Sundays are buzzing with activity throughout the week. Provision ranges from lunch clubs for the elderly to activities for the whole family, such as Messy Church, or ones directed particularly at children, such as Kidz clubs.

Map of the diocese in 1888

Map of the diocese in 1926