Читать книгу Home SOS - Katherine Brickell - Страница 11

Chapter One Fire in the House Introduction

ОглавлениеHome SOS casts a vital spotlight on the domestic sphere as a critical, yet overlooked, vantage point for understanding the trajectory of Cambodia, a Southeast Asian nation known for its encounters with genocide (Hinton 2005; Kiernan 2002), reconciliation and peacebuilding (Ciorciari and Heindel 2014; Gidley 2019; Hughes and Elander 2017; Öjendal and Ou 2013, 2015; Peou 2007, 2018; Richmond and Franks 2007), post‐conflict transition (Öjendal and Lilja 2009; Peou 2000), and economic transformation (Hughes and Un 2011; Hughes 2003; Springer 2010, 2015). During Pol Pot’s genocidal reign (1975–1979), the home was rendered ‘ground zero’ in efforts to break apart families, intimacies and other relations of the former society. As a lifeworld ‘constituted by relatively stable associations, relatively known and shared histories’ (Bhabha 1994, p. 42), it had to be destroyed. Cambodia needed to be ‘killed’, to cease to exist both literally and symbolically, for the radical communist revolution to be built (Tyner 2008, p. 119).

After decades of upheaval and displacement, Cambodia moved through a so‐called ‘triple transition’ (Peou 2001, p. xx): from armed conflict to peace, from political authoritarianism to liberal democracy, and from a socialist economic system to a market‐driven capitalist one. The accelerated neoliberal path that the country has taken, and its unravelling experimentation with democracy, has had a profound influence on domestic life. In this political economy context, at a time of formal peace, Home SOS contends that home is, once again, a spatial epicentre of intimate violences, thought to have been consigned to its genocidal past. It is not only that wounds remain in dysfunctional marriages and traumas carried through time, but rather, with its formal end, Cambodia opened up to the world, and new wounds have reconfigured and compounded the old.

The dual focus of Home SOS on domestic violence and forced eviction shows that the home is not a ‘pre‐political’ or ‘unexceptional’ space (Enloe 2011, p. 447) separate from these political changes. Its internal intimacies and external‐facing dynamics have the capacity to temper, retell, and rework the grand narratives of change that have so dominated writing on Cambodia. As a pivotal space of bio‐necropolitical world (un)making, the home demands greater scrutiny. It is where the production and destruction of life is perhaps most regularly and intensely expressed, yet it is systematically overlooked in theoretical writing in geography and related disciplines.

The starting point of the book then is the ‘extra‐domestic’ home, in and through which, multiple forms of violence flow and coalesce. This ‘extra‐domestic’ reading derives ‘precisely from the fact that it [the home] had always in one way or another been open; constructed out of movement, communication, social relations which always stretched beyond it’ (Massey 1994, p. 171). The home is host to violences that are played out through the microdramas of daily life, but also through public political worlds that influence, and are influenced by, the domestic situation (Blunt and Dowling 2006; Brickell 2012a, 2012b; Nowicki 2018). Tracing these violences through the realm of the extra‐domestic problematises the narrowness of ‘crisis‐affected’ and ‘crisis‐prone’ descriptors limited to countries and regions experiencing war, conflict, and natural disasters. The intimate wars of domestic violence and forced eviction render the home a crisis‐affected and crisis‐prone space, both inside and outside, of these formal hostilities and calamities. Home SOS thus works to reaffirm and reprioritise the home as a political entity that is foundational to the concerns of human geography.

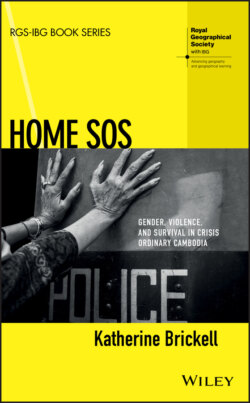

More specifically, the book contributes to geographical scholarship on intimate geographies of violence and crisis that have not commanded as much attention as high‐profile public ones. The concern of Home SOS is not simply the enactment of domestic violence and forced eviction but how they are experienced and contested. While neither domestic violence nor forced eviction are formal emergencies, the title of the book deploys the SOS distress signal. This internationally known code has been used by forced eviction women activists in Cambodia as a political statement of emergency to oppose their dispossession (Figure 1.1). Their public SOS calls reassert the importance of imbuing everyday structural violences with a sense of scholarly and political urgency that is so often lost, given the seeming intransigence of routine violences (Philo 2017; Scheper‐Hughes 1996).

Figure 1.1 SOS sign in Boeung Kak Lake, Phnom Penh, 2011.

Source: © Ben Woods. Reproduced with permission.

Charting the journey of Cambodia’s first‐ever domestic violence law (DV law), alongside women’s housing activism against forced eviction, I examine how each usher women’s bodily presences from the home into the wider world to make life more liveable. They are, on the face of it at least, refusals for the injustices they embody to be known only in the private realm. As I go on to demonstrate, however, the political economy of Cambodia has conspired to stymy, and in some cases quash, the transformative potential that each might hold.

Based on over 300 interviews, conducted over the past 16 years, the research presented in Home SOS pivots around experiences of intimate violence and the work of survival as told through the gendered stories of ‘ever‐married’ Cambodian women.1 It incorporates continuums and rearticulations of violence from the Khmer Rouge period and includes discussion of episodic shocks and endemic precarities played out in the lifeworlds of participants in the four decades since. In what follows, I explore the ways in which home and intimate life are sustained, contested, and disrupted through marital relationships ‘in crisis’ and which are lived out, and shaped through, this history and newer manifestations of crisis taking place.2 The book therefore aims to document, make visible, and interpret women’s experiences of violence and survival in, and through, the home as an irreplaceable centre of significance in still challenging times. Looking to the home as the spatial epicentre of married life, the book contributes to the now growing body of research in geography on family and intimate relations (see Tarrant and Hall 2019 for a recent review). While noting that home and family are not necessarily coterminous, and intimate relations are not only marital but take a variety of forms, I take the marital home as my central referent point. A little over a decade ago, the family was considered an absent presence in the discipline (Valentine 2008), and marriage as the ‘commonest form of social cooperation’ had been neglected in the social sciences on the grounds of its ubiquity, taken for granted, and more‐than‐individual character (Harker 2012; Jackson 2012). By showing how marriage is a foremost social relationship through which domestic violence and forced eviction are articulated, Home SOS further questions the validity of these grounds for dismissal.

In Cambodia ‘family is at the core of society’ and is traditionally headed by a man who is invested with meeting its economic and social needs, and women its housekeeping and child rearing responsibilities (Ministry of Womens’ Affairs (MOWA) 2015, p. 23). It is normatively accepted that Cambodian wives must provide ‘shade’ including ‘shelter, safety and prosperity’ for their children (Kent 2011a, p. 197–198) and are responsible for the management of conflict in family life. Women in Cambodia have primary duty for the social reproduction of their households and, in turn, they gain important public value through domesticity. Nineteenth century normative Cambodian poems such as the Chbab Srei (Rules for Women) refer derogatorily to women who walk too loudly in the house as to make it tremble, and should a woman act too forcefully, neglect her household responsibilities, or not fulfil the entirety of her husband’s demands, then blame can be assigned to her for the breakdown of their marriage. Divorced women are typically regarded as socially incomplete in Cambodian society (Ovesen, Trankell, and Öjendal 1996) and a Khmer proverb reminds daughters that, ‘you should be married before you are called an old maid’ (cited in Heuveline and Poch 2006, p. 102). Women’s homes and bodies therefore risk being considered as lacking when marriages fail. To avoid this, women in Cambodia are invested with the demands of ensuring the harmony, intimacy, and warmth of their marriages and wider family in the home. Domestic violence and forced eviction not only challenge women’s capacity to fulfil these expectations, but they also threaten the material and symbolic foundations of everyday life from which life is grown and sustained. Both domestic violence and forced eviction have, therefore, a disproportionate impact upon women given the intensities of homemaking in comparison to men.

The twin focus of Home SOS on domestic violence and forced eviction arises, in part too, from their status as human rights abuses, which witness the ‘mutual absorption of violence and the ordinary’ (Das 2007, p. 7). The home is, perhaps, the most ordinary of spaces on which geographers train their research and analysis. An intimacy sustaining vision of the ‘ordinary’ home, however, is complicated by domestic violence and forced eviction. which both disrupt the safety, stability, and comfort that the space should normatively afford. As Lauren Berlant (1998, p. 281) argues,

intimacy … involves an aspiration for a narrative about something shared, a story about both oneself and others that will turn out in a particular way. Usually, this story is set within zones of familiarity and comfort: friendship, the couple, and the family form, animated by expressive and emancipating kinds of love … This view of ‘a life’ that unfolds intact within the intimate sphere represses, of course, another fact about it: the unavoidable troubles, the distractions and disruptions that make things turn out in unpredicted scenarios.

Berlant’s conception of intimacy brings to the fore the ‘unpredicted scenarios’, which are perceptible and woven into the ordinary. Under this guise, the ‘ordinary’ cannot be equated with the benign and harmless (Mayblin, Wake, and Kazemi 2019); its study requires that scholars go beyond and interrogate the taken‐for‐granted. The potential for such discordance, ambiguity, and negativity in experiences of ordinary life has been a motivating focus in the critical geographies of the home sub‐field, which emerged in the mid‐2000s (Blunt and Varley 2004; Blunt and Dowling 2006). As Jeanne Moore (2000, p. 213) argued, there was a ‘need to focus on the ways in which home disappoints, aggravates, neglects, confines and contradicts as much as it inspires and comforts’. Decades on, there is room to think more about how to theorise the home as a space that absorbs as well as repels ‘trouble’. The fact that in the family geographies sub‐field ‘everyday processes of family conflict, trouble and disruption’ currently only ‘occupy a marginal space in the geographic literature’ (Tarrant and Hall 2019, p.4) lends further weight to this task.

In Home SOS, I take the ‘crisis ordinary’ (Berlant 2011) as the lead conceptual frame through which I deepen theoretical engagements on intimate geographies of violence in these sub‐fields, and geography more broadly. Domestic violence and forced eviction, I contend, are both instantiations of the crisis ordinary, ‘when the ordinary becomes a landfill for overwhelming and impending crises of life‐building and expectation whose sheer volume so threatens what it has meant to ‘have a life’ that adjustment seems like an accomplishment’ (Berlant 2011, p. 3). Home SOS explores this social theory through a grounded, embodied, and long‐running account of crisis ordinaries that are unfolding in Cambodia and that allow elite men, in particular, to maintain the balance of power at the expense of women and their homes.

The book that follows is an ambitious, expressly experimental one, which rather being a single‐issue monograph is dedicated to the integrated study of domestic violence and forced eviction. Domestic violence and forced eviction are typically understood as discrete and unconnected violences, the former usually discussed as a type of interpersonal violence and the latter as a ‘violence of property’ (Springer 2013a, p. 608). However, a core argument made in the book is that the intimate injustices and precarious journeys that domestic violence and forced eviction embody are also intimately linked and, in some instances, simultaneously faced in women’s lives. I read and weave these interconnections through hybrid yet complementary theoretical engagements with the crisis ordinary and survival-work, bio‐necropolitics and precarity, intimate war and slow violence, law and lawfare, and rights to dwell (see Chapter 2). Drawing on literatures from development studies, women’s studies, anthropology, politics, and international relations (IR), and spanning development, legal, political, and social geography, I provide, ultimately, an original book‐length study that combines domestic violence and forced eviction to offer relational insights between these violences.

In this introductory chapter I set up some of the major and interconnected arguments that the book takes forward: first, that domestic life is lived and manifest in and through crisis ordinaries; second, that domestic violence and forced eviction necessitate what I call ‘survival-work’; and, third, that they are both forms of gender‐based violence. I then turn to the research trajectories that led to the convergence of the domestic violence and forced eviction research and material. I also include reflection on key overarching methodological approaches taken and how these are reflected in the content and ethos of Home SOS. Finally, I move on to the structure of the book and summarise its findings.