Читать книгу Lesbian Pulp Fiction - Katherine Forrest V. - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

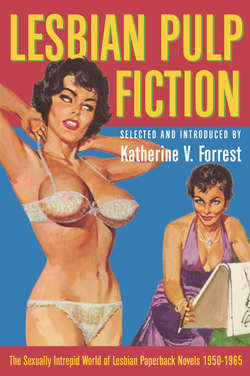

Spring Fire

ОглавлениеIt was a gray afternoon, and the sun was hidden behind a sheet of dull sky, with the wind kicking the leaves along the curb in front of the Tri Epsilon house, where they stood talking.

“I’ll pick you up after the meeting,” he said. “We could squeeze in a few beers at Rick’s.”

“Not tonight, Jake-O. I’m tired. Think I’ll catch up on sleep. Those Monday night chapter orgies wear me down.”

She was thinking that Mitch would be waiting in the room. Before dinner she would tell Mitch that she was going out with Jake when the chapter meeting let out, and then she would surprise her. She’d say, “Do you think I could go out with him when I knew you were up here? I can’t kid myself any longer, Mitch.” Maybe that would erase the nervous undercurrent of tension between them since Jan had gone. It would be more dramatic that way, surprising her like that.

“OK, I’ll give you a ring.” He took the pipe out of his mouth and leaned over to kiss her quickly. Jake was funny the way he sang aloud in the streets. He walked away singing, “Oh, here by the fire we defy the frost and storm,” and Leda heard him as she walked up the steps and came into the front room of the house. The thought came that if Jake were gone forever, it would be strange, but if the choice were to be made, it would be Jake who would go. Not Mitch. Was she upstairs? She teased her own curiosity, prolonging it, sweetening it by tarrying in the hall downstairs.

To the left of the dining room there was a small alcove, with square boxes and names printed evenly above each one. In her box there was an envelope with her name scrawled on the outside, and no postage or address. Girls were coming down the stairs, milling around in the hall waiting for the dinner gong. They were reading papers, playing cards, singing at the piano, and talking together in close, separate groups. Leda took the envelope to the scarlet chair in the corner near the entrance to Mother Nessy’s suite. She ripped the seal open and held the thin notebook paper in her hand.

Dear Leda,

This letter is for you alone. Please tear it up when you are through.

More than anything else I want you to understand what I’m going to say here, and why I’m saying it. I want to leave the sorority and become an independent. Maybe it’ll be the best thing for me, and maybe it’ll be just another defeat, but I have to do it. Leda, darling, you know that I love you. You know it, even though I haven’t shown it the past few days. I’ve been worried and afraid, and now I know for sure what’s wrong with me. I suppose I should go to a doctor, but I don’t have the nerve, and I’m going to try to help myself as best I can.

Lesbian is an ugly word and I hate it. But that’s what I am, Leda, and my feelings toward you are homosexual. I had no business to ask you to stop seeing Jake, to try to turn you into what I am, but please believe me, I didn’t know myself what I was doing. I guess I’m young and stupid and naïve about life, and I know that you warned me about the direction my life was taking when you told me to get to know men. I tried, Leda. But it was awful. Even Charlie knows what I am now. I think that if I go to an independent house, away from you, the only person I love, I’ll be able to forget some of the temptation. If I stay in the sorority, I’ll only make you unhappy and hurt you. I love you too much to do that.

Please announce that I am leaving during the chapter meeting tonight. Don’t tell them why, please, because I want to straighten myself out and I don’t want people to know. Tell them that I thank them for all they’ve done, but that I’d rather live somewhere else because I don’t fit in here.

I know how you’ll feel about me after reading this. I’ll try to stay out of your way. Tonight I am going to eat dinner downtown, and then during chapter meeting I’ll pack most of my things and move to the hotel until I get a room at the dorm. Robin Maurer is going to help me.

There’s nothing else to say but good-bye, I’m sorry, and I do love you, Leda.

Mitch

The dinner gong sounded out the first seven notes of “Yankee Doodle.” Mother Nesselbush stood in the doorway of her suite. She looked down at Leda, who was sitting there holding the paper the note was written on, not moving. It was customary for one of the girls to lead her in to dinner. Marsha usually handled the task because she was president, but Marsha was hurrying to finish the last-minute preparations in the Chapter Room for the meeting. Mother Nesselbush cleared her throat, but to no avail. Leda sat still and pale and Nessy bent down.

“Are you all right, dear?”

“Yes.”

“That was the dinner bell, you know.”

Leda said, “Yes.”

“Would you like to escort me to my table?”

Leda looked up at her, a thin veil of tears in her eyes, so thin that Mother Nessy did not notice. She could sense the waiting around her, the girls waiting to go into the dining room, Nessy waiting, the house-boys who served the food waiting for her. Standing slowly, she crooked her arm and felt Nessy’s hand close on it as they moved across the floor into the brightly lighted hall, past the six oak tables to the long front table and the center seats.

A plate of buns went from hand to hand, each girl taking one and passing the plate mechanically, reaching for it with the left, offering it with the right, as they had been taught when they were pledges. The bowl of thick, dried mashed potatoes came next, and the long dish of wizened pork chops, the bowl of dull green canned peas, and the individual dishes of cole slaw. When Leda tasted the food, she felt an emetic surging throughout her body and she laid her fork down. Around her there was a churning gobble of voices that seemed to slice through her brain like a meat cleaver. Mother Nessy stared after her when she went from the room.

“She said she was sick,” she told Kitten, “and I knew it when I saw her before dinner. Poor thing. There’s a flu epidemic going around, and I’m willing to bet my life she’s got the flu.”

The car was gone from the driveway. Leda put on the sweater she was carrying and ran down the graveled drive. In her hand she clutched her felt purse, and at the corner she caught a taxi.

At the Blue Ribbon there was a crowd of students waiting at the rail with trays, sitting in the booths with books piled high beside their plates, pushing and standing near the juke box with nickels and dimes, the pin-ball machines ringing up scores in her ears as she looked for Mitch.

The Den was quieter, and the waitresses were lingering lazily around the front of the room near the bar, where a few boys munched liverwurst sandwiches and drank draught beer. The bartender dropped a glass and cursed enthusiastically. Leda pushed the revolving door and felt the cold autumn wind.

Mac’s, Donaldson’s, the Alley, French’s, Miss Swanson’s, all of them alive with hungry students swarming in and out, the smell of hamburger predominant in each cafe, the sizzling crack of French fries cooking in grease on hot open grills.

“Ham on rye.”

“One over easy.”

“Hey, Mary, catch the dog.”

“Well, hell, you’re almost an hour late!”

Leda stood finally on the curb in front of Miss Swanson’s. She fumbled in her pocket for a nickel and ran into the drugstore on the corner. She made a mistake dialing the number, and she held the hook down until the nickel came back and then tried again. When the voice answered, there was a long wait, the far-off sound of voices shouting down the halls, and then the answer, quick and flip. “Robin’s out to dinner. Call back later.”

Her heart was pounding, and she could feel the perspiration soaking her body. If Mitch was eating with Robin, she might have it arranged already. Where was she eating? With the car, she could be anywhere, but it was unlike her to drive far at night. The clock read seven-thirty. In half an hour the chapter would meet and Mitch would go back to the house for her bags. Leda shivered in the night air and wished she had found Mitch before she had a chance to see Robin and carry her plan through. Now Leda would have to tell Marsha she was sick, that she had gone for medicine because she was sick and she could not attend the meeting. She would be in the room waiting for Mitch when she came.

A car swerved away from her as she stepped off the sidewalk into the street. The cab driver grunted, and skirted the curb narrowly as he drove fast.

“Hurry!” he said. “You girls always gotta be someplace fast. That’s all I hear is ‘Hurry, driver!’ Hurry, hurry, hurry.”

“Marsha’s in the Chapter Room,” Kitten said. “Thought you were sick.”

Leda said, “I am.” She found the door to the room locked, and she knocked three times fast and once slow.

“Who goes?” she recognized Jane Bell’s voice.

“Pledged in blood,” Leda said. “Promised in the heart.”

“Enter.”

The bolt was slipped off and Jane Bell stepped back. She was wearing a silky white gown with a deep red scarf on her hair, drawing her hair back behind her ears. There was a sharp odor of burning incense in the dark room, lighted only by five single candles on a small table covered with the same silky white material. Marsha knelt at the table, arranging a red velvet-covered book with a black marker on the open page. When Leda walked in the room, panting, her face damp and hot, Jane stared at her.

“My gosh,” she said, “you look feverish.”

“That’s what I came about. I can’t attend the meeting tonight. I feel lousy.”

Marsha looked up from the book at Leda. There was an angelic look to her face by candlelight, a look that she was fully aware of, cultivated and practiced. When she conducted the weekly chapter meetings, this look lent an air of piety to the conduct of the service. With the members of the chapter standing in a solemn semicircle before her, she felt that there was something spiritual about her leadership, celestial and sacrosanct.

“We’re having a formal meeting tonight,” she told Leda, as if to persuade her sickness to end.

“I see you are. I’m sorry. I just feel lousy.”

“You look feverish,” Jane Bell remarked again.

“I hope you feel better.” Marsha smiled. “Did you know that Mrs. Gates, our Kansas City vice-counsel, gave us three new robes? Jane has one on.”

Jane twirled and the robe floated on her gracefully. Inwardly Leda thought, Jesus! Oh, silly Jesus! but she pacified them by touching the material and exclaiming, then apologizing again. She backed out of the room just as the electric buzzer gave the signal for the members to line up in the hall and prepare to enter in single file.

The halls were still, the pledges confined to their rooms for study hour. Leda found the room dark. Mitch had not come yet. She struck a match and lit a cigarette, and in the blackness she went to the window and watched the street. Ten dragging minutes later the convertible pulled up in front of the house, and Mitch slammed the front door and hurried up the walk. Leda lay down on the bed, watching the cigarette smoke curl to the ceiling, and waited.

After the light went on in the room, Mitch felt a flood of surprise in her stomach as she saw Leda. She shut the door and set Robin’s large empty suitcase on the floor. Leda sat up and looked at her.

“You’re going to pack now?” she said.

“Yes. I thought you’d be in chapter meeting.” She tried not to look at Leda, but she could feel the girl’s eyes piercing her, stopping her attempts to avoid those eyes, and she went to the bureau and began removing socks and handkerchiefs and scarves.

Leda let her click the suitcase open, and watched her while she placed the things inside it. She could feel the sharp edges of the letter against her chest there near her bra where she had put it before dinner. With her left hand she reached down and fished the letter out and stuck it under her pillow.

“I decided,” Leda said finally, “that the least I could do was to say good-bye to you.”

Mitch felt choked up and agonized with desire. She scooped out an armful of slips and panties and pajamas, and thrust them in there with the other clothes. Her lips formed the word “Thanks,” and she meant to say it, but there was no sound. On the floor of the closet there were fluffy swirls of dust near her tennis shoes, and she brushed them away with her hand. She tossed the shoes onto the bed, and took the chair from the desk over to the closet to reach the boxes at the top.

Leda said, “Want any help?”

“No. Thanks, though. I can do it myself.”

“You’ve got an idea,” Leda said, “that you can do everything yourself. I don’t know where you got that idea.”

“Sometimes it’s up to yourself,” Mitch said.

“You’ve got a lot of ideas, I bet. I bet you’ve got thousands of good ideas.”

The box slipped from Mitch’s hand and fell to the floor, spilling out two round hats, one black, one brown, both alike—round and plain.

“Someday you’ll find out that most of the ideas don’t work. None of them work.”

Mitch stopped tying the strings on the top of the box and looked up at Leda. “What are you trying to say?” she asked. “What are you trying to tell me? You never say anything right out. You always talk around and make it hard.”

“I’m trying to say, don’t go. Going isn’t the answer.” The tears came in her eyes, and Mitch looked away at the shoe bag on the closet floor. She thought of Robin, her friend, of the swimming team, of other years and anything to keep them from being the same, but this made it worse and the sob started low in her throat. Then Leda bent and caught her shoulder and held her, kneeling on the rug, listening to the stifled crying.

“Mitch,” she said, “don’t go. Don’t leave me, please.”

“But you know what I am. I told you what I am in the letter.”

“I don’t care. Mitch, I don’t care.”

“I can’t stay with you. I won’t feel right, I—”

Leda put her hand on the girl’s face and felt the tears. She turned her face and put her lips on the salty moistness. “Come on over to the bed,” she said. “Get up, Mitch, and come on over to the bed.”

Mitch lay down with her face buried in the pillow, and Leda sat on the edge, her hands stroking Mitch’s hair.

“Can you hear me, Mitch? Listen, it doesn’t help to run away. You don’t think it helps, do you? It doesn’t help.”

“No,” Mitch sobbed. “I can’t stay here. I can’t bear to see you every day and know what I’m doing to you.”

“What are you doing to me? What in hell are you doing to me?”

“I’m a Lesbian,” Mitch answered. “That’s how I feel about you, too. I’m not like you—with Jake and everything.”

“Oh, God, Mitch! All right, listen. I love you, you crazy kid. I don’t have to label my love, do I? Do I have to say that it’s Lesbian love? OK, then that’s what it is. It’s Lesbian love, pure and simple. Ye gods, I’ve known about myself for years. I didn’t run away. I didn’t walk out and run away. You gave me plenty of reason to. You were the first one to come along and blow up my little plan for hiding the way I am. You think you’re doing something to me! Oh, Mitch! If anyone’s doing it, I’m doing it. I’m doing it because I love you.”

Mitch brought her head up from the pillow and turned over on her side. “But you said it,” she said. “You said you couldn’t love a Lesbian. You said—”

“I said so damn much, didn’t I? You’ve got to understand, Mitch. I don’t like what I am. If Jan ever knew, I’d take a razor and slash my wrists. I couldn’t live with people knowing, and pointing and saying, ‘Queer’ at me. No one knows but you, and I guess I never would have told you if you hadn’t started to leave. Do you think it’s easy to admit it? It was different when I could say it wasn’t this way, that I was bisexual and all that rot. Bisexual—that’s sort of like succotash, isn’t it? Only this succotash hasn’t got any corn in it. It’s straight beans!”

“What about Jake?” Mitch blew her nose and sat up. “What about all the time you spend with Jake?”

“Maybe I’m trying to prove something to myself. Part of me is trying to say that I’m not what I am. That’s the part of me that everyone knows—the alluring Leda, the queen, Jan’s daughter, an apple never falls far from the tree. Out with Jake every damn day to keep myself away from what I really am. Want to know what sex with him is like? It’s like dry bread, that’s what it’s like. Like dry bread!”

Leda got up from the bed and reached for her cigarettes on the desk. She felt relieved, cleansed, as though her mind had been emptied and she was free. She walked over to the suitcase on Mitch’s bed and picked up the clothing, taking it in her arms to the drawer. “You want this all put back, don’t you?” she said to Mitch. “You won’t leave me?”

“No,” Mitch said. “I’m going. Robin arranged everything, and—oh, Leda!” They stood in the center of the room holding one another, their lips fastened hard, their arms strong around each other. Leda’s hand reached for the buttons on Mitch’s blouse.

“Just stand still,” she said. “Just let me take everything off and look at you. I want to look at you.”

The skirt fell to the floor, and the blouse. Mitch stepped out of her shoes and stood before Leda.

“I want to love you,” Leda said.

Her hands stroked Mitch’s body gently. She leaned over to kiss her lips and her forehead and the closed eyelids. She said her name and held her, feeling the fast beat in her pulse and knowing that she had almost lost her.

The blood beat furiously in Mitch’s throat and she could feel a mounting strength in her legs and arms. With the arrogance of a master, Mitch’s nails dug into Leda’s flesh as she began to pull the sweater and the thin blouse from her shoulders. She let her teeth sink into Leda’s neck.

“No, faster!” Leda cried. “Faster, Mitch!”

Leda’s gasp was one of pleasure and desire and it moved Mitch to more violence, pinning Leda’s wrists behind her back and jerking at her skirt.

Neither of them heard the door open.

They turned in time to see Kitten and Casey framed in the doorway, eyes big, mouths dropped, and they fell apart from one another when the door was slammed, and the sound of feet running down the hall was as loud and fast as the beating of their hearts in that room.

It was a long time before they talked. Mitch lay dumb with horror, never forgetting the look on their faces as they had found her that way with Leda, unclothed and wild like a fierce animal. Sitting with her head hung, her hands pressing at her eyes, Leda was the first one to speak after the minutes passed as they would in a slow nightmare when nothing is real.

She stood up and picked the blouse off the floor. “Look,” she said. “I’ll go and talk to Marsha. That’s where they ran to. I’ll go and straighten it out.”

“How?”

Leda reached in the closet for a fresh blouse, and straightened her skirt so that the zipper was pulled and on the side. She ran a comb through her long hair, and her hands were trembling.

“I’ll explain it somehow. Marsha’s gullible, and I’ll explain it. I have to go now, or they’ll have a chance to talk and spread the story.”

Mitch said, “‘I’ll go too, Leda, I’ll go too. What’ll we say?”

“No!” Leda put her hands over her face and shook her head. “I’m sorry I yelled. We’ve got to handle this just right. You stay here. It’s better for me to go alone.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes. Look, get into bed. I’ll turn the light out and you stay here. If anyone else comes by, pretend you’re asleep.

She waited while Mitch pulled her pajamas from the suitcase on her bed and threw the suitcase down on the floor, before she stepped into the pants and the coat. After she got in bed, Leda snapped the light out and went back by her own bed before she opened the door to go.

“Don’t worry,” she said. “Don’t worry at all. And stay here!”

In her hand, as she walked toward Marsha’s suite, Leda clutched Mitch’s letter, wrinkled and folded on the long sheet of notebook paper. Her eyes were set and determined, and there was a tight line about her lips.

Under the heavy violet and black quilted robe, Mother Nesselbush wore a voluminous peach-colored flannel nightgown. Her hair was rolled on large black pins so that it pulled at her scalp and gave her round face a bizarre expression like that of a mild Jersey cow. Her skin shone with “night cream,” and until everything began, it was with conscious effort that she stifled the great yawns that exposed her pressing lethargy, as well as her gold-studded molars.

Everything began when Marsha shut the door to Nessy’s suite and pressed the lock down to secure it. Beside those two, Casey, Kitten Clark, Jane Bell, and Leda shared the secrecy of the meeting that was about to commence. Marsha stood while the others sat in various positions around the small anteroom.

“I don’t need to tell you that this gathering is an extreme emergency. We must all pledge never to reveal what we hear. Our whole reputation as a national sorority is at stake, to say nothing of the reputation of Tri Epsilon on the Cranston campus. I’ve asked Jane to come because she’s a member of the Grand Council. Fortunately, our other two members were on the scene when this thing happened. And Leda will explain her part in it. Nessy, we’ve inconvenienced you tremendously, but this is too terribly serious.”

Mother Nesselbush protested that she was not disturbed, and that she was only too thankful that she was called on. She straightened her drooping shoulders and sat forward intently.

“Maybe you better tell how it started, Casey,” Marsha said, leaning against the small mahogany table with the vase of daisies set on it.

Casey was excited. Her face was animated and colored with the heat of her adventure. She uncrossed her legs and leaned forward from the couch.

“It was right after chapter meeting. Kitten and I were going up to talk with Leda about her being nominated for Christmas Queen, and about the campaign we were going to plan. Well, we were kind of pleased and everything and I guess we just never thought of knocking, and when we got in there—well, this is kind of hard to say—we found Mitch naked and she was attacking Leda. I mean, she was kissing her and pulling at her clothes.”

“What!” Mother Nesselbush paled and caught her jowls with her pudgy hands. “Oh, no!”

Leda’s knees felt watery and loose, and her knuckles were white in a tight fist.

“Well,” Casey went on, “Kitten and I ran like the devil—”

“I’ll say we did,” Kitten broke in. “I was never so scared in my life. If you could have seen it! I didn’t know what to think. I didn’t even think when I was running.”

“What did she do when you opened the door? Gosh, Leda, you must have been crazy with fear.” Jane Bell looked over at Leda after she said it, and shook her head and wrinkled her forehead in disbelief. “Absolutely crazy with fear!” she repeated.

“You poor, poor darling,” Nessy said. “To think of it!”

Marsha moved forward and held her hand up for silence. “After that,” she said when everyone settled down, “Leda came to me in the suite. Luckily, Kitten and Casey had come right there, so the story hasn’t spread.”

“What about Susan Mitchell?” Mother Nesselbush snapped. “Where is she now?”

“You better carry on from here, Leda.” Marsha sat down on the floor, close to Nessy’s chair, and waited while Leda found words. Of course, they believed the story. It had been easy to tell it, Leda thought; not easy, but the only way. It had been the only way to tell it. Strange how she had thought that she would do it just this way if they were found, in that quick flash of intuition a second before they were found. She remembered another day when she was a child alone in her room, and in the midst of it she had heard Jan’s footsteps down the hall. If they stopped, if Jan came in the room, then she would say that she had shooting pains from cramps, and that she had been tossing on the bed and was hot and out of breath, and she would even cry to show that the pains were bad ones. But she would not spoil that moment there with herself for anything. All of the thoughts came quickly to Leda, solved in seconds, so that there was never any defeat. Now again she was not defeated, because they believed her. There was Mitch upstairs, waiting, trusting, but the time was now, downstairs, and Leda began slowly, her words careful and well remembered.

“Mitch is upstairs in bed. She’ll stay there, and she won’t talk to anyone. I told her that I would explain it, and I’m going to try to. I can’t explain it so that everything is over and forgotten as I know she hopes I will do, but I am going to try to be fair to her.

“First of all, with everyone’s permission, I’d like to read a letter.”

When she finished the letter, Mother Nesselbush rolled her eyes in utter horror. “I declare,” she said. “I do declare!”

“You see,” Leda said, “I suspected that Mitch had a crush on me. She was jealous of Jake and of the time I spent with him. I knew that, but I never dreamed the kid was in love with me like this. You know how I am. I call everyone honey and darling, and I guess the kid took me to heart. Then, after I told her to get some boy friends, she got mad and tried to ignore me. I didn’t pay any attention until I found this note in my mailbox before dinner tonight. Well, you know how I acted at dinner.”

“And I thought it was just the flu,” Nessy said. “Land!”

“So I decided that the only thing I could do was to try to help the kid. At least persuade her to wait until morning. I didn’t know what kind of condition she was in. She might do something dumb like confiding in that Robin Maurer. Then the whole campus would know. I didn’t know what to do. I couldn’t wait till chapter meeting and talk it over with you kids, because she’d be gone by then. I tried to handle it myself.”

“Who’s Charlie?” Kitten said. “Is he that independent? What does she mean, he knows?”

“She imagined that, I’m sure,” Leda answered. “I guess they had a fight or something and she thought he knew. The kid is really naïve.”

“She didn’t look naïve when Casey and I saw her.”

“Let me finish, Kitten.”

“Well, Lord, we don’t want it all over campus that one of the Tri Ep pledges is queer. That’s all the independents need.”

“I tell you, he doesn’t know. No one does!”

“Let Leda finish,” Marsha said.

“She brought a suitcase with her and was ready to go. I persuaded her to wait until morning. I thought that by that time I’d be able to do something—talk to Nessy or Marsha or someone. She got undressed to go to bed, and—then she—attacked me. Thank God you kids came along at the right time.”

“What did she do after they left the room?” Jane Bell asked. “I can’t even imagine this!”

“That brought her to. You see, she really went out of her mind for a minute. After the door slammed, she came to and became herself. I quieted her as best I could, and told her it would all be OK. She was scared to death, poor kid.”

“Yeah, poor kid!” Casey sneered. “She belongs in a cage!”

“I don’t know,” Leda said. “I can’t help feeling sorry for her.”

Nessy said, “You showed great presence of mind, Leda. Why, if it had been me, I would have just shrieked my lungs out!”

“You weren’t even yelling,” Casey said.

“And it’s a good thing she didn’t. If it ever got around the house—Lord, I hate to think.” Kitten reached for a cigarette and snapped the flame on her lighter. “That’s one thing we’ve got to be damn careful about. We’ve got to keep it between us. We’ll have to think of some other reason for getting rid of her.”

“Maybe I can do it,” Leda said. “Look, maybe I can convince her that the best thing for her to do is to go to the Psych Department. I’ll tell her I think she was right to want to move to the dorm, and then we’ll be rid of her and she’ll never know the difference. We can keep it all hush-hush.”

Jane Bell groaned and scratched her head. “No, that’s no answer. She’d blab it to one of the doctors and then it’d get back to Panhellenic. Besides, no telling what she might do at the dorm.”

Inwardly Leda shook at the danger of her own suggestion. But no matter where Mitch went, there was the danger of her telling her side of the story. Of someone believing it. Who’d believe it? The letter was written perfectly, leaving Leda free of any implication, and there was no other proof. Nothing. She felt stronger then, fear lending new armor.

“You know,” she said, “the kid will probably try to blame me. She’ll probably say I had something to do with it. You know how people get when they’re up against a wall.”

Mother Nesselbush giggled. “Leda, our queen,” she said. “Now really, do you think anyone would believe the child? She’s obviously demented!” Her face changed and became grave. “Girls, I don’t think the decision is ours to make. We must think of the reputation of the house. Tri Epsilon stands for honesty and loyalty, to ourselves and to the school too. This is a matter for the dean’s office, girls, and I assure you, Dean Paterson is a very discreet person. She’ll handle this with utmost concern for our welfare.”

“I agree with Nessy,” Marsha said. “It isn’t anything we can decide. We can only pledge ourselves to secrecy. No other member of the sorority is to know about this. Now, let’s promise it.”

“Promised!” Kitten said. “That’s for sure.”

“I’d be embarrassed to tell anyone else,” Casey commented. “Even now it embarrasses me.”

Jane Bell stubbed her cigarette out in the ash tray. “I don’t have to remind anyone,” she said, “that if the pledges ever learn about this, we’ll be in danger of losing the entire pledge class.”

Marsha stepped forward to the middle of the room. “We all know the consequences. It could be anything else but this. Homosexuality just leaves a horrid taste. We’d all have to pay, even though we had nothing to do with it, just because it happened under our roof. We’d be the brunt of thousands of miserable jokes. You remember the year the Sigma Delts had those two terribly effeminate boys in their pledge class? Remember what happened the day they woke up and found the signs all over their front yard? That’s just half of what we’d get.”

Leda remembered the signs. They were large cardboard ones with bright red paint. They said, “Fairy Landing,” and “Sig Delt Airport—Fly with our boys!” For weeks, the jokes out at the Fat Lady and down at the Den and the Blue Ribbon centered around the Sig Delt house. No one ever knew how it all started, or whether there was any basis to it all, but everywhere you went you heard the sly remarks, and saw the wry grins that attended the cracks about “those fairy nice Sigma Delts.” She had been a freshman then, but after two and a half years it was all very fresh in her memory. Everyone remembered, long after the boys left campus.

“I’ll call the dean,” Mother Nessy said, “the first thing in the morning. The only thing we can do tonight is go to bed and try to sleep. Leda, you’d better make up the couch in here.”

“I’m afraid Mitch will be suspicious. I mean, I told her I’d explain everything. She’ll probably wait for me to get back.”

“Oh, joyous reunion,” Casey said. “Holy God!”

“You mean you’re going back to that girl, Leda? Why, I won’t hear of it!”

“Look,” Marsha said calmly, “maybe it’s the only way. We can’t have her getting out in the halls and trying to find Leda. I mean, she won’t be violent like that again, will she, Leda?”

“No, I know she won’t. You don’t understand. The kid is scared out of her wits now. She wouldn’t lift a finger.” Leda felt queasy, listening to them picture Mitch as a wild beast roaming the halls for prey. She would have to make them believe that she was wise to go back up there to Mitch. But not too anxious. “Of course, I confess it isn’t going to help me sleep any to know she’s in the room, but—”

“No!” Nessy said. “I simply can’t have it. I’m responsible.”

Mitch would be waiting. Leda would have to go back, or Mitch might run to Marsha and confuse the story, ruin it—even if they didn’t believe her.

“I know,” Marsha said. “Kitten and Casey and I will wait in the bathroom. Leda, you go in and see if it looks OK to stay there. If it does, you can tell us by coming down to the john. If it’s not OK, then you can tell and we’ll think of something else. I mean, if you think Mitch is going to act up.”

“That’s fine,” Leda said, “and I think it’ll be OK. You don’t know this kid like I do.”

Kitten grinned. “Obviously,” she said. “Who’d want to?”

“All right,” Nessy consented reluctantly, “but I won’t sleep a wink. Not a wink!”

Marsha moved the tab back on the door and opened it. “Now, for heaven’s sake,” she whispered, “look nonchalant. Pretend we were all in talking to Nessy, and that’s all. Some of the kids might still be up. And Leda, when you come down to the john, make it subtle if anyone’s there. Then we can go to the suite and talk.”

Mother Nessy took Leda’s arm before she left the room. “You promise me,” she said, “you promise me that if that girl gives any indication of acting up again, you’ll just jump right out of that room and come down to me. I don’t care what the hour is.”

Leda said, “Don’t worry, Nessy, and I promise.”

The five girls climbed the main stairs slowly, Marsha attempting vaguely to whistle a bit from “On, Wisconsin.”

It was taking Leda a long time. What could she say to them? Mitch was numb with torment, and the sheets on her bed were wrinkled and halfway off the mattress from her perpetual turning and moving as she waited. The ticking of the tin clock on the dresser sounded frantic and Mitch made the ticks come in three beats in her mind—Les-bi-an, Les-bi-an, tick-tick-tick. Leda was one too. The thought foamed in Mitch’s brain and hurt her. She did not know why she felt dirty when Leda told her that she was a Lesbian. She thought she should have felt happy and glad that they were two. But she did not want to be one. Abnormal.

From far off she could hear the sweet voices of a fraternity serenading a sorority house down the street.

She turned the light on and looked at the face of the clock. It was eleven-thirty. Leda had been gone too long. She saw Leda’s half-full package of cigarettes on the desk, and she took one from the pack and lit it. It tasted strong and sour and she squashed it in the ash tray and turned the light off again.

Tomorrow, she decided, she would move out of Tri Epsilon and into the dorm with Robin. If she and Leda weren’t put out of the sorority, she would leave anyway. But she could not leave Leda. “I love Leda,” she said softly to the darkness, “even though we’re both that way. I wish she wasn’t that way.”

The dream came in a half fit of consciousness. Her mother was very beautiful, with black hair that came to her shoulders, and clear green eyes. Mitch loved her. She wore pants and shirts and combed her hair back, wet from her swim, and went to her mother with jewels and furs that she had stolen for her to have. Her mother smiled and accepted them. Mitch heard her say, “You’d better not steal all the time. I couldn’t love a thief.” She ran down a long alley to escape the police who were looking for her. It was late when she got back to the Tri Epsilon house and her mother was there with the police holding her arm. Her mother was laughing. She said, “You didn’t know I was a thief too,” and the policemen led her away. Diamonds were spilling out of her mother’s pocket as she went down the steps with them.

She thought she had been asleep for hours, but it was only twenty minutes to twelve. Leda must be in trouble. The dream put a ragged edge on her anxiety. The bed was a sight, rumpled and torn apart as though it had been ravaged. Mitch straightened the sheets and fluffed the pillow. In the corner of the room by the bureau her clothes lay where Leda had taken them off, kicked to the side. Mitch picked them up and brushed them off.

Les-bi-an, Les-bi-an, tick-bi-an…

Mitch thought, I can get a job. Leda and I can run away and I can work someplace. If they put us out of the sorority I won’t go home. Leda won’t either, because of Jan. Colorado is nice, or California. She had a vivid picture of the open convertible speeding through purple and rust landscapes and along white desert with the cactus along the roadside. She added glorious black nights and ten thousand brilliant stars, and a warm wind whipping at their faces. It was no good. She hated the picture. Why? A slow self-disgust chewed at her and called her coward, but she was still afraid. She promised herself to be strong when Leda came back, no matter. Whatever Leda said, Mitch would not reveal her fear. Leda loved her and this was the price. Be strong for two. The words on the storybook she’d had as a child came dancing on the scene of her mind: “Now We Are Two.”

Part of it was the way Leda acted when she had said “No, faster! Faster, Mitch!” It seemed far away and morbid, as though there was an insane spark to their love that made them fierce and careless. Sitting on the side of her bed, under the harsh light of the electric bulb overhead, Mitch could not know herself in that scene. She reasoned that she was not violent. Never violent. Yet there was still the faint taste of blood on her tongue, and the way she knew she had been strong there with Leda.

Don’t blame Leda. You’re trying to blame Leda.

There was a sound of steps in the hall. Mitch caught her breath when they came to the door. It was Leda returning.

“What are you doing with the light on?”

“I had to find out the time.”

“I told you not to leave it on. I told you to go to bed.”

“I just turned it on. I was afraid.”

“Well, it’s over, so go to bed.”

“Over?”

“Yes. It’s all right.”

“Wh-what did you say? How did you explain it?”

Leda’s face was composed and placid. She took her soap from the tray on the rack behind the door. Her washcloth hung over the bar above the shoe bag and she put that with the soap. “I’m going to wash my face. I’ll tell you when I get back. Look, it’s over. There’s nothing to worry about.”

Mitch just sat there staring.

“Get in bed. I’ll be back.”

“I’ll come too,” Mitch said. “I didn’t wash yet. Wait for me and I’ll come too.” She started toward the bureau.

“No!” Leda’s tone came out sharper than she had meant it. She could not look at Mitch’s face, which was alive with a new hope. Her words went to the rug. “No, it’s better if you stay in bed. I told them you didn’t feel well. You see, that’s how I explained it. I said you were sick.”

“Oh,” Mitch said. “I—” She sat back on the bed and rubbed her forehead.

Leda walked toward the door. “Look, just get in bed. I’ll be back in a minute. I’ll tell you then.”

“OK, Leda.”

Before Leda turned the doorknob, Mitch’s eyes met hers.

“Leda?”

“What?”

“Thanks.”

When she was gone, Mitch felt sick and dull all over. She was ashamed of the way she had thought about Leda. The thoughts seemed to tease her still, pricking her knowledge that Leda had made everything all right, that now there would be no reason to run and hide. Steadily she rebuilt the structure of their love, amplifying it with Leda’s courage and with her own indebtedness to Leda. She could feel the physical ache for her down to the tips of her fingers, replacing the enfeebled numbness, charging it with renewed vigor. Healing time had conquered the doubt and fear, and her servility was sworn in that moment. Mitch felt humble and brave in the darkness of the room.

A tongue of light cut through the black as Leda opened the door and slipped back in. Mitch could hear her putting things away and getting out of her clothes. The thud of her shoes on the floor sounded unusually heavy in the silence. Mitch threw the sheets and blankets back and went over to her.

“For God’s sake, no! We just got out of one mess.”

“I’m sorry, Leda. I just feel so—”

“Get back in bed. My God!”

The covers felt itchy on her chin and she pulled the sheet up higher. She could hear Leda getting in bed.

“I know you’re upset,” she said. “I should have known better than to come over to you, Leda. I’m sorry.”

“Forget it.”

Mitch waited. Leda would tell her now—everything that had happened. The minutes crept and the clock began the game, ticking out the word.

“Leda?”

“What?”

“You said you’d tell me.” Mitch’s voice was thin and meek. She didn’t mean to keep at Leda like that, but she had to know.

“OK. I said you were sick. I said you went to bed sick and you were feverish when you came after me.”

“D-did you say that I came after you?”

“Well, hell, I had to say something! When they came in the door, that’s what they saw.”

“Oh.”

The wind blew papers off the desk and they ruffled along the floor, the noise quick and airy.

“Leave them,” Leda said. She settled back and the noise stopped.

“Well, did they believe you? What about—My God, I was naked!”

“You were sick! I told them you were sick, Mitch!” Mitch wanted to stop the angry tone. She lay quiet and another paper chased across the room and landed on top of her on the bed.

“Mitch, I’m sorry I’m so snappish. I just feel like hell. It wasn’t easy.”

“I know what it must have been like, Leda.”

“It was hell.”

“Does—does anyone know? Anyone else, I mean?”

“Just Marsha and those two.”

“It’ll be hard tomorrow. What’ll I tell them when they ask what was wrong?”

Leda turned her pillow over on the side. Then she got up and put a bottle of ink on top of the papers so they wouldn’t blow any more. “It won’t be hard,” she said. “They won’t even talk about it. Just go along as though nothing happened.”

“Leda, I don’t know how to thank you.”

“Quit saying that! What in the name of God do you think I am, your holy savior?”

The night air was crisp and Mitch snuggled down in the covers. She closed her eyes and tried to sleep, but she kept listening for Leda to say more. When she didn’t, Mitch said, “I just want to say one more thing, Leda. I’ll always stick by you—always. You mean more to me than anyone I know.”

Leda didn’t answer.