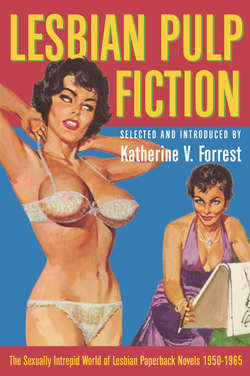

Читать книгу Lesbian Pulp Fiction - Katherine Forrest V. - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Women’s Barracks

ОглавлениеThat day, too, we were assigned to housecleaning.

To ward evening, a truck unloaded straw for mattresses—and also a batch of five new recruits, who were immediately sent off to peel vegetables in the kitchen. Ursula and I had just finished cleaning the three bathrooms. She had been chattering rather easily most of the day and I had begun to feel that I understood this frail girl who nevertheless was streaked through with decided, even passionate elements of character.

As we came out on the stairway we noticed one of the newcomers crossing the hall, laden with a huge pile of straw. It was a lady. A lady such as one saw in films. At first glance, the lady appeared fairly young—thirty or thirty-two. But on closer scrutiny one saw that she was somewhat older.

Ursula stood still and murmured, “Isn’t she beautiful?”

The woman was tall and extremely blonde—a peroxide blonde. Her hair curled in ringlets over her forehead and fell in waves alongside her face. Her nose was fairly long, but quite narrow and very slightly arched, giving her an air of distinction. She was heavily made up. Ursula stood stock-still, a wisp of a girl wrapped in her long beige smock, watching the passage of this beautiful creature. The woman had such a marvelous scent! And in passing, she threw Ursula a smile that was as perfumed as the woman herself.

At that moment our sergeant-cook appeared, roaring, “Hey, you there, the new one—Claude! What are you doing with that straw? You’re supposed to be in the kitchen!”

To our astonishment, we beheld the one called Claude raise a snarling face over her pile of straw, and from her artfully made-up mouth there came forth one of the most violent replies that I had ever heard. As for Ursula, she stood agape. “You can go to hell!” the lady spat at the sergeant. “Just because you’re a sergeant, don’t think you can get away with anything! First, I’m going to fix my bed and when I’m through, I’ll come and peel your potatoes, and if you don’t like it you can kiss my behind!”

The sergeant-cook must have realized that this was no little girl from Brittany, for she went away without saying a word.

Now Claude turned toward us. “Can you imagine, talking to me in such a tone of voice! What does she take me for—her servant? More likely, she’d be mine! I volunteered out of patriotism, and not to be treated like an inferior by a conne like that!”

It was strange, but the coarse words with which her speech was peppered seemed to lose their vulgarity when they were spoken by Claude. She had a very beautiful voice, cultured and modulated, the sort that could permit itself the use of slang.

“Can you tell me where to find the switchboard room?” Claude then asked. “That’s where I’m to bunk. I’ve got to take charge of the telephone.”

An assignment of this sort seemed prodigiously important to us. Full of respect for Claude, we showed her the little room near the entrance that had been set aside for the telephone operator.

Claude dropped the straw on the floor, went to the window, opened it, and leaned on her elbows, looking out into the street.

Facing our barracks was a large hotel, and in front of the hotel entrance stood the doorman, very tall, very thin, with graying hair and thin lips. His cheeks were highly rouged, his eyelids were painted a bright blue, and he bowed with feminine grace before every man who entered the hotel. Then he resumed his haughty nonchalant stance, staring directly before him at the windows of our barracks.

“You could take him for the ambassador of Peru,” murmured Claude. We had no idea why “ambassador” and why “Peru,” but the phrase enchanted Ursula and she started to laugh.

“How old are you, child?” Claude asked her.

This time Ursula replied, “Seventeen,” without hesitation.

Claude placed her hand on Ursula’s head and stroked her soft hair. I felt as though I were intruding. “You have the air of a tiny little girl, and you’re ravishing—you’re like a little bird,” Claude said.

It was obvious that this was the first time anyone had told Ursula she was ravishing. And yet, because it was said in another person’s presence—mine—it was quite normal, almost a conventional remark.

Ursula never forgot her feelings at this first meeting. When she spoke about it to me later she said that Claude’s voice was so gentle, Claude’s hand was so soft that she wanted to reply, “Oh, and you are so beautiful!” but she didn’t dare, and she uttered the first banality that came to her. “I’ve been here since yesterday. I’m from Paris. Where are you from?”

Claude was about to answer when a corporal appeared—a third one. We seemed surrounded by corporals. This was a large girl, rather gentle and reserved, she had charge of the office. She had some forms in her hand and she gave them to Claude to fill out.

Ursula tugged at me, and we left.

Our aristocratic Jacqueline was the first to receive a secretarial post. She would always be first everywhere, with her enchanting face and her air of being owed the best, and yet this was so natural to her that we could not resent her manner. She returned at noon, absolutely delighted with her office. Her lieutenant was a man of excellent family, she announced to us, highly cultured. And he had already invited her to have lunch with him tomorrow. Of course, he had a wife and children in France.

Soon most of us were assigned to work in various offices at GHQ. I became, for the time being, a file clerk and the operator of a mimeograph machine in the Information Bureau. But the Captain had no idea what to do with Ursula. Most of us could type, at least; Ann could drive a car; but Ursula had no accomplishments. Finally the Captain put her down as sentry for the barracks.

Ursula remained seated all day long at a little table by the entrance, keeping a registry book in which she noted down all of our comings and goings. Opposite her was the switchboard room, where Claude was stationed. Through the half-open door she could glimpse Claude’s glistening blonde hair. From time to time, Claude came out of the little room for a chat. She still wore that same wonderful perfume. But with tender dismay one night Ursula asked me if I had noticed that Claude had little creases at the sides of her mouth, and white hairs mingled with the blonde. Indeed, Claude could have been her mother. And in those first days I felt that this was what drew Ursula to Claude, the wish that she had had a mother as gay and amusing as this woman, with her inexhaustible store of gossip about all the celebrities in Paris.

But soon the stories Ursula brought back from Claude were less innocent. Ursula was fascinated and yet a little puzzled by the ease with which Claude related her bedroom experiences; she had slept with most of the currently fashionable actors and writers of the capital, and she kept up a continuous stream of intimate chatter about her lovers to the girl. Ursula would repeat Claude’s gossip, somewhat in awe, and somewhat as though wanting reassurance that there was nothing wrong in her adoration of Claude. Claude would tell her, “I absolutely adored that boy, and then suddenly I had enough of him. My only love was always my husband, but he’s a dog. He drinks too much, and he’s a fairy, damn him! As soon as we’re together, we fight. Luckily, I had Jacques. He was my great consolation. He was still a child, a high-school boy. He used to come to me after school. I trained him. I made him my best lover.”

Ursula couldn’t get over her astonishment at this woman who adored her homosexual husband but fought with him, and who had so many lovers, and who was so much at ease about it all. The world of grownups had always seemed distant and mysterious to Ursula. With Claude, that world became even more distant, and all the values that Ursula had so painfully established for herself were overturned.

But one thing was certain: Ursula felt that the one person who really cared about her was Claude. Big Ann was pleasant and sometimes brusque; the aristocratic Jacqueline irritated her, perpetually wanting to fuss over her and take charge of her; Mickey was a clown who made her laugh; and I suppose I was just someone who listened, someone she found it easy to talk to. Ursula complained that the corporals scolded her endlessly, and the Captain could scarcely remember her name. But Claude talked to her, confided in her as in a friend, called her her little bird, stroked her hair, smiled at her with her perfumed smile. Claude knew so many stories, she was afraid of no one, and she had a way of looking at Ursula with her black eyes, a way that made Ursula forget every desire except to remain close to Claude as much as possible.

One night there came an order for the sentry to sleep in the switchboard room with the telephone operator, so as to make sure that the service would continue in case of a serious air attack. I helped Ursula drag her iron cot into the little telephone room. Her heart must have been beating with joy. What heavenly evenings she would pass with Claude!

That same evening, Claude decided to throw a secret little party in the switchboard room. We organized it among a few of the girls, and sent Ursula out to the corner pub to fetch some bottles of beer.

Ursula put on her cap and hurried out. It was the first time she had been out since her arrival at the barracks. It was raining. Down Street was narrow and dark. Ursula found her way to the pub, which was brightly lighted and full of smoke, and crowded with soldiers in various degrees of drunkenness. They called out to her, “Oh, Frenchie! Look at the French girl!” Ursula told me later that she didn’t know what to do with herself. The soldiers’ eyes shone and their lips were wet with beer. They had thick red hands. Ursula’s heart fluttered. She kept her eyes fixed at a point on the wall while she was being served. Finally it was finished. The soldiers tried to catch hold of her arms, but she freed herself and ran out. Ursula plunged toward the barracks as to a refuge.

I was standing in the doorway of the switchboard room when we heard Ursula’s hurrying footsteps on the stairs outside. Claude brushed past me into the hall and opened the door for her. She stood there in the doorway, so shining, so blonde, with her khaki shirt partly open, revealing her white throat. Ursula pressed herself suddenly against the woman, and Claude held her in her arms. Her hands gently caressed Ursula’s hair.

I can only suppose that Claude forgot my presence, or perhaps she thought I had gone on into the switchboard room. But I remained in the doorway, and I saw Claude gently press Ursula’s head against her full breasts, separated from Ursula’s cheek only by the khaki shirt.

It was not hard for me, then or later, to understand Ursula’s feelings. After her first, unnerving visit to a pub full of roistering soldiers, she had hurried along a dark, alien street and found again at the end of it Claude—beautiful, shining Claude—who at that moment must have seemed to her the very embodiment of warmth and safety and gentleness.

Claude raised Ursula’s chin with one hand, drawing her face closer, and suddenly, in the dimly lighted hall, she kissed Ursula on the mouth. It was a quick light kiss, like a brush of a bird’s wing, a kiss so discreet as not even to startle the girl.

Just then Ann and Mickey came along, with their drinking glasses hidden under the jackets of their uniforms.

In the switchboard room, a little clock sounded nine. The corporal of the guard had closed her eyes to our soiree, since Ann had given her to understand that Warrant Officer Petit was invited, and, naturally, any corporal reporting our little party would only be making trouble for herself. (I had already noticed that Ann seemed to be born with a sense of how to manage things in the Army.)

Petit was the last to arrive. The little room was filled with cigarette smoke. Claude had taken off her uniform, and was now wearing a dressing gown—blue with little white dots. She was seated on the bed with one of her legs folded under her, and the other kicking a red slipper. A lock of platinum hair fell over her forehead. A cigarette trembled in her lips, while she was engaged in reading Mickey’s palm.

Petit surveyed the room, with her scrunched-up eyes of a man of the world. Petit might readily agree that Claude was beautiful, but a woman like Claude had no interest for Petit. To our warrant officer, Claude was only a dilettante. One might pass a pleasant evening with a woman like that, but nothing else. At bottom, to the Petits of the world, Claude was a pervert, a perverted woman of the sophisticated milieu, but a woman in spite of everything. As for Ursula, Petit scarcely glanced at her, obviously summing her up as a nice little thing, but nothing special. She looked at Mickey. Her expression said, “A little fool.”

Ann was standing against the table with her arms crossed. She had rather thick muscular arms and broad masculine hands. Petit poured herself a glass of beer, and drank it down without stopping; she was satisfied. It was said that her last two intimate friends had remained in France on the farm where the three of them had lived before the war. She was all alone here, and felt herself aging. Soon enough she’d be fifty years old. In Ann, she must have seen herself as she had been at twenty-six—solid and robust, with a deep voice and a man’s hands. Ann looked directly into her eyes, and from her relaxed and satisfied expression Petit seemed to know that everything was going well. It was probably then that Petit decided to use her influence to have Ann made a corporal as soon as possible. That would make things a lot simpler.

Much was to happen between the women who were at Claude’s little party, and when I traced back their stories, I found that the threads began to be woven together on this night.

Mickey was laughing as usual and playing the little comedian. Claude knew that she was making no mistake; she had wide experience with men, with women, and with life: Mickey would go far for adventure, even though she was still a typical demi-vierge. She was pretty, in her gawky way, she was ready for anything, she was gay, a good comrade, and well liked by everyone. Claude predicted a rich lover and a long voyage for her. Then Claude turned her gaze upon little Ursula, sitting silently at the foot of the bed, and Claude’s face filled with tenderness for the child. A girl still so young, so new, altogether inexperienced and untaught. She must have thought of her own life as a little girl, for despite her bravura manner of an adventuress and a femme fatale, she was born of a provincial middle-class family. Ursula had already brought me Claude’s story of how she had been lifted out of her small-town shell when quite young, through marriage to an elderly, dissipated Parisian who had initiated her into the city’s circles of debauch. He had finally succeeded in completely disorienting a character that was at bottom healthy. Claude had left him at last, and married a younger man, an engineer by profession. But her second husband had his special passion, and had taken a job in London so as to be near one of his male friends. Claude had followed him in May, just before the fall of France, for she was in love with him despite his habit. She was a woman overfilled with love, and her love had to be dissipated. All the love that she might have had for a child had to be used somewhere. And here was this girl, this little Ursula. I think there was the same mothering desire in her love for Ursula that she had felt when that boy Jacques had come to her with his schoolbooks under his arm. And yet there was with it a devouring avidity for something as delicious as a slightly green fruit. It was strange, absurd, but when Claude talked of Jacques one could see that it had seemed to Claude as though she were carrying on in a motherly role, continuing a boy’s upbringing, just as someone who had taught him to wash, to eat, to walk. She, Claude, was also a mother in her way. She had taught him to eat of another sort of food—and she was proud of his progress, with a maternal pride. And little Ursula—how wonderful it would be to watch her little mouth open for the first time, and to see her overcome with happiness, like a child to whom one has just given a beautiful toy!

Even while she kept chattering with the rest of us, Claude studied the girl through the corner of her eye. She smiled at Ursula, and drew her nearer, putting her arms around her, living again the intimate moment in the doorway.

Petit was watching, with a malicious and slightly obscene light in her eyes. She had the air of saying, “I leave her to you. That one doesn’t interest me at all.” But it was flattering to Claude that Petit understood at once. Claude always enjoyed the idea of being considered a dangerous woman.

The barracks had been in existence for more than a month. Every morning we went through our drill in Down Street before hurrying off to our various jobs. One day the Captain announced that a military ball was taking place, to which all of us had been invited.

That evening we were all loaded onto trucks and carried across blacked-out London. As we bumped along, Jacqueline regaled us with tales of the formal balls she had attended before the war, dressed in white tulle. She remembered the family limousine, with the chauffeur in uniform, bowing as he opened the door for the young lady. I suppose she could not help feeling her superiority to most of the girls in the truck, who behaved with a good deal of vulgarity. And I suppose that Jacqueline really had no desire to go to a dance at a training camp, where she might be pawed by any soldier from anywhere. But neither did she want to remain alone in Down Street. Besides, it might be amusing to see what a soldiers’ dance was like, just once.

The truck made a few too many sudden stops. The driver must have found it amusing to jolt our bunch of girls so that we fell all over each other. Most of us laughed, but Jacqueline protested, for her back was again giving her trouble. One of the women called her a snob, and told her to cut out her mannerisms.

When I really came to know Jacqueline, I understood that she suffered from a perverse need to impress everybody. That night, she hoped that she would faint, so as to make that woman regret her words. But it didn’t happen, and she didn’t quite feel like feigning a loss of consciousness, as she sometimes did by letting herself slide into a kind of feebleness that readily took hold of her. But the bouncing truck brought tortures to her back. She had been suffering these odd spells ever since that night of her flight and her accident. I knew the pain was real enough, but I sometimes wondered why she had jumped from the roof of the house in the first place. Was it really because of that pair of perverted drunkards whose children she was taking care of? Was it really to escape from them? Or had she done it because of some need she carried within herself, a need for drama and for disaster?

I was astonished, and filled with admiration for her honesty, when Jacqueline told me once that she often asked herself the same questions.

“There seems to be a tradition of melodrama in my family,” she said. “One of my first memories is of being surrounded by people, all of them talking about the airplane crash that killed my father.”

Soon after that, Jacqueline told me, there had been a stepfather, elegant, attentive. She recalled the household scenes, later on, between her mother and her stepfather because he would kiss her when she came home from school. She spoke of the attempted suicide of her stepfather.

She had left home to escape this concentration of hatred and misfortune, veiled by riches and good manners. But her fate followed her wherever she went. Or was it perhaps that she carried it with her? Jacqueline wondered.

A week after her arrival in England, in the first family to which she had come on an exchange visit, the husband had died of a heart attack. After that she had lived with a couple, a man and his wife, who came in turns each night to knock on her door. She hated them. She wanted to punish them, to bring about some sort of explosion, to provoke a drama. Yes, she said, she knew now that it was drama that she wanted most of all. She could just as well have left quietly. No one would have kept her back by force. But she had preferred to stage an escape—to jump. She had had visions of herself as a beautiful corpse beside their house.

But instead, Jacqueline had howled in pain under their windows all night long and no one had come. In the morning she had dragged herself to her room. It was finished. The drama had failed.

Soon afterward, she had read a newspaper item about a feminine contingent being formed in the Free French Forces. That was her salvation. All the history of France passed before her eyes—pictures remembered from her childhood: the parades of July Fourteenth, Jeanne Hachette, Ste Geneviéve, the queens of France, the Marseillaise, Verdun—she was going to become part of all that! To save France! To avenge the armistice, the great shame! Her father would have been proud of her—that legendary father who had fallen from the sky like Icarus.

As soon as she was well, she had volunteered. And now she was a soldier, mingled with the women of the people. There were indeed several girls of good family—Ursula, Mickey, a student of pharmacy, the daughter of a consul—but they were the exceptions. Most of Jacqueline’s comrades now were women of an entirely different sort from any she had ever known before.

She spoke with contempt for all the members of her self-satisfied family—so sure of their prerogatives, so certain that it was a great distinction for anyone to be invited to their table—and yet, was she herself so different from them? Since she had come to live at the barracks, I knew that Jacqueline had her doubts. It was true that she accepted any sort of physical task without the slightest complaint, and that she did her best to accomplish it through pride—just to show us that she was perfectly capable of scrubbing the floor or peeling potatoes. But there were so many coarse women, with the tales of their cheap affairs with men already resounding through the barracks—she hated them all. They permitted themselves to be taken to filthy little hotels. They went to bed with sailors, copulating like animals. She, Jacqueline, would never permit a man to take her at his will. When the others talked of their cheap affairs, Jacqueline said nothing. But I knew she was thinking of the lieutenant in her office, so eager to please her, bringing her books and flowers and gifts, inviting her to the Mayfair or to the Claridge. All the men were in love with her; Jacqueline had become used to that, and she would have been astonished if it were not so. She loved to watch the shine come into their eyes, and to provoke their compliments. The other evening in a taxi, after being taken to dinner, she had permitted a young officer to kiss her on the mouth and then had come running in like a child, her eyes sparkling, to tell me about it. It was fun, it was really like one read in stories, like playing with fire, to feel him burning close to her, and to be able to put him off whenever she wished. Before the war, in France, she had been engaged to a handsome lad, quite well-to-do, belonging to her own world. Jacqueline had permitted him to kiss her and to fondle her breasts, and she had found it amusing to hold him off after that, and to feel him trembling with desire, a slave of his desire for her. It was as though she had made a discovery, that in addition to being born to an aristocracy in which one always was in the position of deciding how other people should behave, she had been born into the aristocratic sex, for it was the woman who could always decide, always command, in relationships with men. It had been a pleasant discovery. Jacqueline had been seventeen at the time.

The dance was in full swing when we arrived. The men welcomed us with shouts and cries of joy; they were mostly French, though there was a scattering of uniforms from other nations—Polish, Norwegian, and Belgian. I liked dancing, and found myself in a little circle of swing enthusiasts. Everybody was learning the Lindy, and I danced with one after another in a strange exhilaration so that I scarcely knew or remembered with which boy the dancing went well. They were still all boys to me.

Mickey was seized by a master sergeant of the Air Corps, who squeezed her tightly as they danced. He was short and slightly bald, but Mickey said he was nice enough. Mickey was never especially particular. She liked to have fun and was willing to taste out of any dish, finding them all pleasant. As she danced, soldiers called to her. They assessed her with an expert air. Her mouth especially excited them—an arched red mouth with the upper lip slightly advanced, as though the girl were constantly ready to be kissed.

While they danced, the sergeant kissed her throat. For form’s sake, Mickey pretended to be shocked. But even the sergeant could see well enough that she was not at all offended.

I looked around for Ursula, but she didn’t seem to be anywhere in the room. I learned later that, after having danced with a fat soldier who was nearly drunk, she felt that she had had enough, and sought to escape. The cigarette smoke was so thick that it stung her eyes almost to the point of tears. She was afraid of these men, didn’t know what to say to them, and was terrified merely at the idea of being touched by any one of them. She saw a door and fled outside. There was a little courtyard, and the fresh evening air made her shiver. Ursula sat down on the steps. The cool air caressed her cheeks, and she shook out her hair, relieved in her escape. Then she noticed that a soldier, quite young, was sitting on a crate in the courtyard, and watching her. There it is, she thought. I have to leave this place, too.

But in order not to appear ridiculous, she told me with her quaint nicety, she remained for another moment, planning to get up and leave as though she had just come for a breath of air.

She kept her eyes averted from the soldier so as not to give him an excuse to speak to her. The music came from the hall—muted, but reaching them nevertheless. In there, a voice was bellowing “Madelon.”

Suddenly the soldier said to her, “It’s better out here than inside, don’t you think?” And as soon as she heard his calm voice, tinged with a slight foreign accent, Ursula felt reassured. Now she looked at the soldier. She could scarcely see him in the darkness, but he had a very young air and seemed rather small in stature. She replied, “Yes,” and didn’t know what else to say.

They remained silent for a long while. Ursula was suddenly quite astonished to hear her own voice break the silence.

She said, “Have you been in England long?”

The soldier answered, “I’ve been here three days. Last week I was in Spain, and it’s only about fifteen days since I was in France.”

Now Ursula looked at him with a kind of awe. He came from France! Only fifteen days ago, he had walked on the earth of France and spoken to the people of France and looked at the trees, the sky of France. It seemed to her that she had been in London for years rather than months.

She raised her head and watched the searchlights sweeping the sky. It was beautiful to see. The alert had sounded, just as it did every evening, but there had been no sound of aircraft. The German planes must have headed somewhere else instead of coming over London.

“Aren’t you cold?” the soldier asked. He spoke so nicely, with so much gentleness in his voice, that Ursula said she was touched. She shook her head. He was probably not French. He had an accent, but Ursula couldn’t tell from what country. And yet he spoke perfect French.

He was silent again for a little while, and then he said, “I admire you for joining the Army. It’s not much fun for the men, but for women it must really be hard.”

And now Ursula began to speak. Whenever she knew she was to be in the company of young men, she worried her head for days in advance to prepare some conversation, and she confessed that her voice always sounded affected to her own ears. Young men had always seemed members of another race to her, mysterious beings with whom she had no point of contact.

But this evening in the dim courtyard, Ursula found herself talking freely to the unknown soldier. She told him about her life in Down Street. She described Jacqueline, “absolutely ravishing, but a little bit artificial.” Mickey, “a good comrade, and so funny”; Ann, “everybody thinks she’ll be the first to get her corporal stripes”; Ginette, who “talks nothing but slang, used to be a salesgirl, and can sew her own uniforms to measure.” She spoke of Claude, “very intelligent, very generous,” who was her protectress. Then suddenly she saw it all, all of her comrades as we were in the mornings, tense, badly adapted to this life, ready to find distraction in anything, hungry for love, each hiding her homesickness at the bottom of her heart. Ursula saw the main hall of Down Street, and her little sentry table. And all day long the phonograph that we had just acquired kept playing the same records, “Violetta” and “Mon coeur a besoin d’aimer.” She spoke about our captain, hurried and distant, a smile always on her lips, calling us her “dear girls,” always giving the impression that she was really going to do something, that she was going to help us somehow, that she was going to create an atmosphere of friendship in Down Street. She talked about this at every opportunity, but after each of her speeches one found oneself just as lonesome and empty as before.

The soldier listened without interrupting her, and when she had finished all he said was, “I understand,” and Ursula felt herself to be truly understood, although she didn’t really know what there was to understand. It seemed to her that this boy comprehended things even before she had grasped them herself. This comforted her, like finding a schoolroom problem solved without having to trouble over it.

We were all ready to go home, and had been hunting for Ursula. Jacqueline opened the door to the courtyard and called, “Ursula, are you there? Ursula, where are you?”

Several voices shouted, “Blackout!” But we just had time to make out two forms, like little children clutched together in the dark. They started up, coming toward us.

“Hurry!” Jacqueline called. “What a relief! At last we can leave,” she said to me.

Ursula came slipping through the door.

The truck was waiting outside, and we piled in. This time I suppose the driver was too tired for his game of jolting us against one another. It was far past midnight, and some of the girls slept, leaning their heads on each other’s shoulders. Suddenly I heard Ursula murmur, “Oh. I forgot to tell the soldier good-bye.”

Just across from us sat Claude; she was holding Mickey’s head on her shoulder. I could feel Ursula stir unhappily. It must have seemed to her that Mickey had stolen her place.

We jumped from the truck, one after the other, and were swallowed in the barracks hall. The house seemed to come awake, invaded like a beehive. Doors slammed, women ran up the stairway, women called to each other from room to room.

Mickey, in pajamas, began to dance in the middle our dormitory. Jacqueline was dressed in one of her elegant flowered linen nightgowns. She sat massaging her face with cold cream. Ann, who was already carrying out the duties of a corporal, even before being promoted, came to remind us that the reveille for tomorrow was for six o’clock, as usual, and to put out the lights. One door after another was heard closing, and the night quieted. There were still a few whispers from bed to bed.

“I was dancing with a sailor, and he’s crazy about me.”

“He’s a perfect dancer. He wants to take me out someplace where we can have fun. You know.”

“He’s going to phone me tomorrow.”

“But honey—it’s amazing—he knows my brother! They went to the same school in Lyons.”

As for myself, I hadn’t met anyone special. I had given my name to a few of the men, perhaps for one of the evenings when a girl is so lonesome she’ll go out with anyone. I’d seen some of the girls do things they probably wouldn’t do otherwise, out of this loneliness, and I hoped it wouldn’t happen to me.

The whispering gradually ceased. Ursula slipped through the room in the dark. She had been in the bathroom, as she was still modest about undressing; she had put on her regulation rose-colored pajamas. This was one of the nights when she slept in the switchboard room and she slipped out of the dormitory, going downstairs.

When Ursula reached the little switchboard room Claude was already stretched out on her narrow camp bed. A storm light stood on the floor. In the feeble light Claude’s bright hair shone. Everything else was in shadow. Outside, the guns began to roar.

Ursula went to sit on the edge of Claude’s bed. The alternate nights that Ursula was assigned to sleep in this room were impatiently awaited. For on these occasions Claude talked to her at length about her husband, about her lovers, about her life before the war. Claude told about places where opium was smoked, and about her travels, and about her pets. It was always passionately absorbing, and Ursula would listen without saying a word, extremely impressed by the number of important people Claude knew, by her countless adventures, and flattered to be spoken to with such intimacy. No one else had ever been like a real friend to her. Especially a really grown-up mature woman.

Ursula adored Claude, and was attracted to her in a special way she could not explain to herself. Sometimes it seemed to her that Claude took particular pains to charm her as though she, Ursula, were a man. But that would be absurd, and Ursula rejected so ridiculous an idea.

That night as she sat on the edge of the cot Claude said to her, “What a whorehouse that dance was! Where did you hide yourself? I drank I don’t know how many glasses of port. Everyone offered me port to drink. I’m sleepy. Kiss me, Ursulita.” She drew Ursula against her as she had that evening by the door, and suddenly she kissed her on the mouth. But this time the kiss was not so short. Ursula felt Claude’s lips burning hers. She didn’t know what was happening to her. She was lost, invaded, inflamed. She tried to get hold of herself as though she were drowning, dissolving in Claude’s arms. Claude drew her into the bed.

Ursula felt herself very small, tiny against Claude, and at last she felt warm. She placed her cheek on Claude’s breast. Her heart beat violently, but she didn’t feel afraid. She didn’t understand what was happening to her. Claude was not a man; then what was she doing to her? What strange movements! What could they mean? Claude unbuttoned the jacket of her pajamas, and enclosed one of Ursula’s little breasts in her hand, and then gently, very gently, her hand began to caress all of Ursula’s body, her throat, her shoulders, and her belly. Ursula remembered a novel that she had read that said of a woman, who was making love, “Her body vibrated like a violin.” Ursula had been highly pleased by this phrase, and now her body recalled the expression and it too began to vibrate. She was stretched out with her eyes closed, motionless, not daring to make the slightest gesture, indeed not knowing what she should do. And Claude kissed her gently, and caressed her.

How amusing she was, this motionless girl with her eyelids trembling, with her inexperienced mouth, with her child’s body! How touching and amusing and exciting! Claude ventured still further. Then, so as not to frighten her, her hand waited while she whispered to her. “Ursula my darling, my little girl, how pretty you are!” The hand moved again.

Ursula didn’t feel any special pleasure, only an immense astonishment. She had loved Claude’s mouth, but now she felt somewhat scandalized. But little by little, as Claude continued her slow caressing, Ursula lost her astonishment. She kept saying to herself, I adore her, I adore her. And nothing else counted. All at once, her insignificant and monotonous life had become full, rich and marvelous. Claude held her in her arms, Claude had invented these strange caresses, Claude could do no wrong. Ursula wanted only one thing, to keep this refuge forever, this warmth, this security.

Outdoors, the antiaircraft guns continued their booming, and the planes growled in the sky. Outside, it was a December night, cold and foggy, while here there were two arms that held her tight, there was a voice that cradled her, and soft hair touched her face.