Читать книгу Lesbian Pulp Fiction - Katherine V. Forrest - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеA lesbian pulp fiction paperback first appeared before my disbelieving eyes in Detroit, Michigan, in 1957. I did not need to look at the title for clues; the cover leaped out at me from the drugstore rack: a young woman with sensuous intent on her face seated on a bed, leaning over a prone woman, her hands on the other woman’s shoulders.

Overwhelming need led me to walk a gauntlet of fear up to the cash register. Fear so intense that I remember nothing more, only that I stumbled out of the store in possession of what I knew I must have, a book as necessary to me as air.

The book was Odd Girl Out by Ann Bannon. I found it when I was eighteen years old. It opened the door to my soul and told me who I was. It led me to other books that told me who some of us were, and how some of us lived.

Finding this book back then, and what it meant to me, is my touchstone to our literature, to its value and meaning. Yet no matter how many times I try to write or talk about that day in Detroit, I cannot convey the power of what it was like. You had to be there. I write my books out of the profound wish that no one will ever have to be there again.

Having lived through this era, in all these years afterward I was certain that I knew in general outline an early literature so very close to me. What I understood of the paucity and the aridity of lesbian literature was the impetus for my own first novel, Curious Wine. Yet in compiling this collection, I discovered the range of our early books and some wonderful, revealing, ongoing scholarship about them. We had more books than I knew, better books than I had thought, and some of them were by writers of international reputation.

I grew up in the post-war 1950s, an idyllic world if you were a straight white male or if you were naïve enough to believe TV’s idealistic “Leave It to Beaver” image of the average American family. It was 1960 when I discovered the seedy lesbian bars of Detroit, when I found my community and came of age. The birth control pill had just been introduced into the United States; it was a mere nine years after our first lesbian and gay organization, the Mattachine Society, had begun in Los Angeles; and five years after Daughters of Bilitis, our first national lesbian organization, had formed in San Francisco. According to the American Psychological Society, I was sick. According to the law, I was a criminal.

From the beginning of the ’50s, popular fiction increasingly reflected the hypocrisy of the times. Tereska Torres’s Women’s Barracks was released in 1950 by Fawcett Gold Medal Books, one of the first books to be published in the brand new paperback format. A publishing sensation, it ushered in what is today termed the golden age of pulp fiction, an era of books so inexpensively produced and priced so low that, as Ann Bannon has said, “You could read them on the bus and leave them on the seat.”

The enormous sales of Torres’s novel ignited an unprecedented boom in lesbian-themed publishing never since duplicated, and the lurid suggestiveness of the three women on its cover became the template for lesbian pulp fiction. Women’s Barracks was the book that led Gold Medal Books pulp fiction editor Dick Carroll to seek out Vin Packer to write Spring Fire, and to advise the young Ann Bannon to rewrite her first novel so that the lesbian subplot would become the central story.

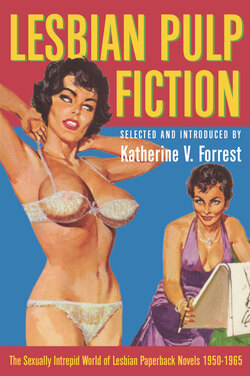

With “morality” seemingly pervasive in the land, lurid covers of paperbacks screamed sex from every retail bookshelf and Americans gobbled up the books by the millions. A new breed of publisher emerged to reap huge pro fits. For lesbian books, cover copy proclaimed our evil in order to meet morality requirements while the come-hither illustrations beckoned the reader into their pages and promised lascivious details. Publishers were not the only ones who profited; popular paperback writers of the time made more money than their hardcover-published counterparts, Vin Packer’s Spring Fire, for example, selling a million and a half copies its first year of publication.

Virtually all writers of homosexual material in those days used pseudonyms, and the men often used female ones—e.g., Lawrence Block, who penned several quite good lesbian novels under the name Jill Emerson: Enough of Sorrow is excerpted here. A considerable number of male writers authored lesbian fiction in the ’50s and ’60s, either from prurient interest or, more likely, to cash in on a publishing boom; their books outnumbered the women’s perhaps five to one. For pre-1970 male-authored works with lesbian content I refer interested readers to Barbara Grier’s invaluable compilation, The Lesbian in Literature and will mention here only a few notable authors: Lawrence Durrell (Clea from The Alexandria Quartet, 1960), D. H. Lawrence (The Fox, 1923), John D. MacDonald (All These Condemned, 1954), John O’Hara (Lovey Childs, 1969; plus numerous short stories), Theodore Sturgeon (Venus Plus Ten, 1960), and John Wyndham (Consider Her Ways, 1957).

Such scant personal information exists about many of the authors that I cannot guarantee the gender of everyone I’ve included. Of necessity, given the times, with one or two exceptions such as March Hastings and Valerie Taylor, the pulp fiction lesbian writers were deeply closeted, and some have dissolved into the mists of history like Cheshire cats, leaving only their printed words behind. Others settled into another kind of invisibility. Marion Zimmer Bradley, who achieved international fame as a prolific fantasy writer (The Mists of Avalon; the Darkover novels), married and had three children, divorced, and began her writing career in the ’60s, writing her lesbian novels under the names Miriam Gardner, Lee Chapman, and Morgan Ives. In later years she refused to acknowledge this work or to discuss any of this aspect of her life.

In the past three decades Valerie Taylor (Velma Young), Ann Bannon (Ann Weldy), and Vin Packer (Marijane Meaker) have emerged to discover our warm welcome, indeed our celebration of them. Valerie Taylor (now deceased) was perhaps the first of our pulp writers to be relatively open and visible, leaving her marriage and conventional life to live in the gay area of Chicago. Militantly active in the gay liberation movement, in 1974 she formed the Lesbian Writers Conference and delivered its keynote address.

Prolific Marijane Meaker (pseudonyms in addition to Vin Packer: Ann Aldrich, M. E. Kerr) reveals in her fascinating memoir, Highsmith (Cleis Press, 2003) that she was a presence amid the Greenwich Village bar scene where she met and became involved with the more famous Patricia Highsmith. Spring Fire (Vin Packer, 1952) owns the distinction of being our first original paperback novel with purely lesbian content. In subsequent years, writing as M. E. Kerr, Meaker has become, according to The New York Times, “One of the grand masters of young adult fiction.”

Ann Bannon, who married early and had two children, held her conventional marriage together while spending weekends in Greenwich Village and portraying in her books the lesbian life she saw, imagined, and longed to live. Her eloquent introductions to the reissued I Am a Woman (Cleis Press, 2002) and Journey to a Woman (Cleis Press, 2002) provide rich reading about how her novels came into being, as does Marijane Meaker in her introduction to the reissue of Spring Fire (Cleis Press, 2004). We will soon learn much more about these writers and their times; both Meaker and Bannon have memoirs in the offing.

Joan Ellis (Julie Ellis), like Ann Bannon, married and had children, and like Meaker, continues a flourishing writing career to this day. A playwright and extraordinarily prolific novelist, she’s written dozens of novels in the family saga, contemporary, and suspense fields for major publishers.

Paula Christian, one of the best known and most popular of all the pulp writers, died in 2002. She did see some of her work return to print; Another Kind of Love, Twilight Girls (a compilation of the novellas Edge of Twilight and This Side of Love), and The Other Side of Desire are today available from Kensington Books.

Sloane Britain (Elaine Williams), the author of These Curious Pleasures (1961) was an editor at Midwood Tower, one of the top pulp fiction publishers; she committed suicide many years ago.

March Hastings (Sally Singer) was sitting in a restaurant across the street from the Stonewall Inn the night the riots began in 1969. She has lived as a lesbian all her life, and for a time was partnered with Randy Salem (Pat Pardee), whose novel Chris (1959) is excerpted.

Tereska Torres is so interesting a figure in the history of the lesbian pulps, her contribution so singular, that she deserves additional mention. After her family fled Europe during World War II, Torres joined De Gaulle’s Free French Forces headquartered in London and for five years came into contact with young women of widely varied backgrounds and sexual proclivities. This experience formed the basis for Women’s Barracks, a fictionalized account of women in wartime, including a bold and candid portrait of a lesbian named Claude. Torres’s later fiction was queer-tinged but never again so notably lesbian nor remotely successful as the book that launched the tidal wave of lesbian fiction.

Fawcett Gold Medal was the leading publisher in pulp fiction (Tereska Torres, Ann Bannon, Vin Packer), but other significant publishers were Avon (Randy Salem); Bantam (Shirley Verel, Della Martin); Beacon (March Hastings, Randy Salem, Artemis Smith); Hillman (Kay Martin); Monarch (Marion Zimmer Bradley writing as Miriam Gardner); and Midwood Tower (Randy Salem, Joan Ellis).

The diversity and quality of what I found not only surprised me, it dictated a necessity for parameters. So, before proceeding further, I’ll explain what those are and why you will not see excerpts from books you may fully expect to find here.

Since the intent (and title) of the collection is Lesbian Pulp Fiction, the decision to do it justice by confining the selections to books published as original paperbacks seemed obvious. Hardcover fiction could be its own separately rewarding venture, at another time. To my dismay, the decision immediately led to the first major omission, the beloved classic novel The Price of Salt by Patricia Highsmith, written under the pseudonym Claire Morgan. Some of us (including myself) first found and read it in paperback; but its initial 1952 publication was in hardcover from Coward-McCann.

The golden age of the lesbian pulps by definition limited the historical timeframe: the first paperback was issued by Pocket Books in 1950. This precluded prior decades and superb novels, including that cornerstone of all our lesbian literature, Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness (1928). Hall’s decade, by the way, saw major lesbian-themed work by giants of world literature, Virginia Woolf and Gertrude Stein. Notable pre-1950 and hardcover novels are listed in the bibliography.

One book excerpted here, The King of a Rainy Country by Brigid Brophy (1957), requires mention for an odd reason: its publisher. Anyone with knowledge of the publishing industry would challenge the presence of Alfred A. Knopf on a list of paperback publishers. But the novel is indeed a paperback, its publisher explaining on the back cover its reasons for this “experiment.” Obviously the format was subsequently deemed an unsuccessful experiment for Knopf.

In Lee Server’s Encyclopedia of Pulp Fiction Writers (2002), Marijane Meaker recalled the instructions given to her by Gold Medal editor Dick Carroll: “The only restriction he gave me was that it couldn’t have a happy ending… Otherwise the post office might seize the books as obscene.” Her introduction to Spring Fire’s 2004 reissue addresses at greater length the conversation with Carroll, and how the mandatory ending of the book—madness and suicide—came to be.

When Three Women (1958) by March Hastings (Sally Singer) was reissued by Naiad Press in 1989 she insisted on revising it to the positive ending she would have given it had she been allowed to do so by editors at Beacon. “To compare the two endings of Three Women would require a book of its own,” she says today. “We all know the publishing climate in those days: same sex affection is out of the mainstream loop in this country, therefore, give it to us overtly for fun and games (hetero titillation) but make sure you tack on an ending of misery, punishment, sadness—that was the commercial voice, loud and distinct.” But she also remembers, “The voice of survival said to me, ‘Give them what they ask for now. You will have your way, later.’ Personally, I was both optimistic and nervous. I had a true and beautiful readership that I cherished. I gave them my integrity in the story-middle, and the feelings there implied our secret pact that one day it would all come right—which it did.”

Ann Bannon remembers no specifically stated restrictions for her first Gold Medal novel published five years later, and avers that not one word was changed in the manuscript of Odd Girl Out she turned in to Dick Carroll. No matter. The tenor of the times, its rigid moral framework, were crystal clear to her, and she produced remarkable, vivid, crucially important fiction within the dictates of that framework. Ironically, a great value of her books today is their unvarnished reflection of their times. Irony indeed when books of this period were for a time regarded as an embarrassment and generally repudiated by feminists during the ’70s and ’80s for their depiction of a “self-hating” world. The historical perspective of our post-feminist world has restored the luster these books deserve for their sexual courage, exemplified by Cleis Press’s reissues of Spring Fire and the Ann Bannon novels with covers reflective of their initial publication.

Back in those days, when the vast majority of lesbians were like isolated islands with no territory other than risky lesbian bars to call our own, and no way of finding more than a few of one another, we were in every way susceptible to accepting and even agreeing with the larger culture’s condemnation of us. We despairingly hoped that stories in the original paperbacks would not end badly but realized that in the view of the larger society, “perversion” could have no reward in novels about us, even those we ourselves wrote. For unrepentant lesbian characters who did not convert to heterosexuality, madness, suicide, homicide awaited, or, at best, “noble” self-sacrifice, such as Stephen Gordon surrendering Mary Llewellyn to Martin Hallam in The Well of Loneliness.

The good news: it’s not true that all but a precious few of these books ended badly.

Most of us believe that The Price of Salt is the first lesbian novel with a happy ending—Therese and Carol end up together—although it’s tempered by the steep price Carol pays for her relationship with Therese, the loss of her son. Aside from the lyrical beauty of Highsmith’s writing (“It would be Carol in a thousand cities, a thousand houses, in foreign lands where they would go together, in heaven and in hell…”), the affirmation of the ending is a prime reason why the novel is treasured by so many lesbians.

The first unadulterated happy ending actually belongs to a novel published more than a decade earlier, in 1938: Torchlight to Valhalla by Gale Wilhelm (reissued by Naiad Press, 1985). A slender, elegant, finely written novel despite its heavily Hemingwayesque prose, its main character is Morgen, a writer; and much of the novel is taken up with her resistance to her persevering male suitor, Royal. When she first sees Toni she understands instantly her every reluctance toward heterosexuality: “I didn’t know what I was waiting for, I didn’t even know I was waiting, but when I saw you I knew.” The love scenes between the two are spare, delicate, and exquisite; and the two women end up together.

Some pulp novels of the ’60s have alternative outcomes, if not precisely happy ones. In Chris, Randy Salem’s classic 1959 novel, Chris rejects both Carol and Dizz to salvage her self. In the Shadows by Joan Ellis (1962) ends with Elaine, who is in love with her brother’s wife, leaving her possessive husband to find her own future. In the final scene of Ann Bannon’s Odd Girl Out, Laura is in a train station going off to “live my life as honestly as I can.”

Some endings are even better. In These Curious Pleasures by Sloane Britain (1961), it’s a triumph for the lesbian reader when Sloane, the novel’s main lesbian character, asks Allison to see if a reservation is available on Allison’s flight to the coast (the equivalent, in those dark times, of asking Allison to marry her)—only to discover that Allison, in hope, had made one for the two of them the day before. In The Third Street by Joan Ellis (1964), Karen leaves her husband for Pat; and in Odd Girl by Artemis Smith (1959), Anne ditches husband Mark, and chooses Pru over two-timing married Esther. All five of the Bannon novels end either with women together or going off to an open future. Paula Christian’s Edge of Twilight (1959) and Another Kind of Love (1961) end positively, as do Valerie Taylor’s The Girls in 3-B (1959) and Return to Lesbos (1963).

The Third Sex (1959) by Artemis Smith is notable on several counts. Its last line is a celebratory toast: “To Ruth and Joan, who are no longer alone.” Like the Ann Bannon oeuvre, it takes place in an authentic gay milieu, contains portraits of gay men as well as lesbians, and features a marriage of convenience—lesbian Joan is married to gay Marc for mutual protection. It also portrays a stone butch (Kim) with a femme (Joan), and Joan’s sexual exploration and fluidity of sexual roles are a precursor to lesbian behavior today.

Clearly, many of the writers of that era, like March Hastings, maintained an integrity of vision and did their best to write what they wanted to write. The jacket copy writers were the ones who did society’s work of condemnation to pass any censorship/obscenity scrutiny. There’s no better case in point than the novel titled Twilight Girl by Della Martin, published in 1961, apparently the only book by this writer—or perhaps the only one she wrote under this name. It’s the story of an innocent teenage butch named Lorraine (Lon) Harris who discovers the shadowy world where she belongs, journeys to self-discovery within that world, but lacks the inner strength to withstand condemnation by the larger society that has all the power over her life and will not allow her to be any part of the person she is. Twilight Girl (to be reissued by Cleis Press) is a fine and remarkably well-written novel, psychologically true and deeply affecting and timeless, one of my major finds. The somewhat awkwardly phrased blurb on the front cover appears in surprising agreement with my assessment: “We sincerely believe this the finest novel ever to treat of the third sex.” Then there is the back jacket copy: “…For unless the blight [lesbianism] is understood, it cannot be curbed…this book should be read by everyone bent on combating the lesbian contagion.”

An inverse law seems to be at work on pulp fiction novels: the better and more honest the book, the more its jacket copy must moralize against it. For lesbian readers, mixed messages indeed. There is real, honest, and painful truth in Twilight Girl, and it raises important questions about the nature of what it is to be lesbian. Its author without doubt knew whereof she was writing. The viciousness of the jacket copy is designed not only to hold off censors but to short circuit any insights by lesbian readers who might add up the truths in this book and begin to question the inimical judgments made of them.

For this reason the original jacket copy on each of the novels precedes each of the excerpts. Judge for yourself the tenor of the times and the differences between packaging and content, how the copywriters wrote for the censors while the writers wrote about lesbian lives as honestly as they could.

Some of the settings reflect the real world of lesbian society. The pervasive presence of the lesbian bar in Twilight Girl and a number of other novels (Ann Bannon, Paula Christian, Valerie Taylor, Joan Ellis, et al) illustrates how crucial the bar society was for gays and lesbians as our only vestige of visible community and support. Alcohol infused this fiction as it did real life. However destructively addictive, it was the necessary ingredient for breaking down inhibitions and fueling courage, and as medication for the chronic pain of being an outcast.

If a lesbian bar setting is the leitmotif of much early lesbian fiction, other lesbian novels tend to be set everywhere else that young women congregate. Spring Fire takes place on a college campus in the Midwest, in a sorority. Bannon’s Odd Girl Out has virtually the same setting. Some titles are self-explanatory: Torres’s Women’s Barracks, and Summer Camp by Anne Herbert. Novels set within the general confines of heterosexual society show a pattern of being those with the most tragic outcomes: The Whispered Sex (1960) by Kay Martin, has a nightclub setting; My Sister, My Love (1963) by Miriam Gardner (Marion Zimmer Bradley), involves the world of music; Three Women (1958) by March Hastings, is set in the art world. Shirley Verel’s exceptional novel The Dark Side of Venus (1962) features novelist Diana Quendon and Mrs. Judith Allard in the upper-class environs of London.

The success of Ann Bannon’s novels is rooted in their urban setting. Rather than an invented setting, they take place in an actual society and community where isolated lesbians of the day longed to be.

So, what kind of excerpts are here, and why did I choose them? Women’s Barracks and Spring Fire were obvious choices because of their pioneering status. Imagine, as you read these two pieces, their impact on readers as the button-down 1950s began. A number of others are included for their sexual content. Lesbian sex is vibrant during any era (somehow we manage), and you’ll see how these writers portrayed our love with smoldering candor during an era of unrelenting repression. In other excerpts you’ll find some of those happy endings I’ve mentioned. A few, like Fay Adams’s Appointment in Paris, demonstrate the variety of background. I chose others for their palpable reflection of what the times were like, what being a lesbian was like. Quality of the writing is another reason why Brigid Brophy’s The King of a Rainy County and Shirley Verel’s The Dark Side of Venus are here. Writers Ann Bannon, Paula Christian and Valerie Taylor are showcased with more than one excerpt because they have earned an enduring popularity over the decades.

Ann Bannon’s five books in particular are by far the most celebrated of our early literature, and she is called “The Queen of Pulp Fiction” for good reason. The author and her books are in a class by themselves. When her five novels were reprinted in Naiad Press editions in 1983, lesbian readers found that she had all this time been in academia (she retired as assistant dean at Sacramento State College), and she herself received the gratitude, acclaim, and embrace of her community. While the Naiad Press reprints in 1983 were instrumental in her rediscovery by readers who first encountered her in pulp format, the recent Cleis Press reissues have revealed her not only to an entirely new generation of readers learning of this history for the first time, but to the media. She has once again found a huge fan base of lesbian, gay, and queer readers, this time looking to her as living history. She has been featured in film documentaries, radio and television interviews, and in many appearances across the country where she speaks in detail about her novels and their times.

Although several of Paula Christian and Valerie Taylor’s stories follow a lesbian character (Val McGregor and Erika Frohmann, respectively), the Bannon novels form a one-of-a-kind saga featuring three characters. They begin with Laura and Beth in Odd Girl Out, and continue in I Am a Woman with Laura and her volatile relationship with quintessential butch Beebo Brinker in Greenwich Village. The dark-edged (in more than title) Women in the Shadows resumes their story. In Journey to a Woman, Beth seeks out Laura in New York, resulting in an explosive mix of all three characters. Beebo Brinker is the final book, a prequel to the four books, delineating the origins of the title character, arguably still the most iconic figure in all of lesbian fiction.

The five books, vividly written and textured with characterization and setting, charged with passion and color, are especially treasured because they portray the only community most of us knew we had back then, the almost mythic Greenwich Village. The Beebo Brinker series without question will remain a part of our permanent literature.

The importance of all our pulp fiction novels cannot possibly be overstated. Whatever their negative images or messages, they told us we were not alone. Because they told us about each other, they led us to look for and find each other, they led us to the end of the isolation that had divided and conquered us. And once we found each other, once we began to question the judgments made of us, our civil rights movement was born.

The courage of the authors of these books also cannot be overstated, pseudonyms be damned. Anyone who has ever written a book can testify to the feeling of personal risk we experience, the sense of stark exposure. The writers of these books laid bare an intimate, hidden part of themselves and they did it under siege, in the dark depths of a more than metaphorical wartime, because there was desperate urgency inside them to reach out, to put words on the page for women like themselves to read. Their words reached us, they touched us in different and deeply personal ways, and they helped us all.

In my case, and with specific reference to Ann Bannon, they saved my life.

Katherine V. Forrest

San Francisco

March 2005