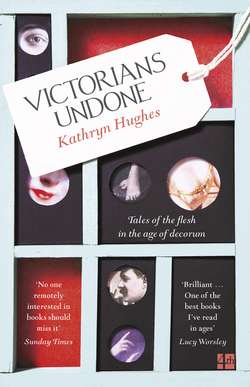

Читать книгу Victorians Undone: Tales of the Flesh in the Age of Decorum - Kathryn Hughes - Страница 10

Charles Darwin’s Beard

ОглавлениеI

On 28 April 1866 the Royal Society held a Saturday soirée at Burlington House, its grand Palladian headquarters just off Piccadilly. Although the event had been timed to coincide with London’s social season, it would be gilding things to describe the occasion as ‘glittering’. This was a gentlemen-only affair, attended by professional men of science and genteel savants in subfusc who gathered to ponder the latest advances in their own discipline, learn about developments in others, catch up with old friends and make contact with new ones. The glaring absence of ladies probably accounts for the glum mood of the twenty-four-year-old Prince of Wales, who had agreed to attend the event only after months of nagging from the Society’s President, General Edward Sabine. Bertie’s sulkiness was hardly helped by knowing that his hosts would have much preferred to be welcoming his father, the late Prince Albert, in his place. Now there was a man you could have guaranteed to take a genuine interest in the exhibits that cluttered the stately interior of Burlington House that night: deep-sea telegraph cables encrusted with barnacles, a machine for extracting oxygen from the atmosphere, photographs of sunspots, not forgetting ‘Mr Preece’s electrical signals for communication in railway trains’. Buzzing around these emblems of modernity were the leading geologists, naturalists and chemists of the day, all avid for a glimpse of tomorrow’s world. The Prince of Wales by contrast looked ‘utterly uninterested’ in any of it, managing to last for little more than an hour before slipping off into the Piccadilly night to begin his evening, this time for real.

Before he left, though, His Royal Callowness was scheduled to shake hands with some of the Royal Society’s most distinguished Fellows. Amongst the select group was a tall, stooped man with a long grizzled beard that appeared to put him in his mid-sixties at least. The Prince clearly had no idea who the old gentleman in the dress suit was, and the old gentleman appeared equally flustered in return. Failing to understand whatever listless remark the young Prince lobbed in his direction, the reluctant courtier gave a deep bow and scurried away.

It is hardly surprising that the Prince of Wales either did not know or did not care that the old man who had just been presented to him was Charles Darwin, the most celebrated scientist of the century, winner of the Copley Medal, and author of the epoch-making On the Origin of Species. What was extraordinary, though, was the fact that most of the other guests at the Royal Society had failed to recognise Darwin too. Indeed, the scientific superstar had been obliged to sidle up to old friends and introduce himself, an ordeal for such a shy man, and a mortification for those who realised too late that they had spent the evening snubbing the most distinguished person in the room.

In fairness, men such as William Bovill MP, Dr Lyon Playfair, General John Lefroy and Sir Wentworth Dilke had not seen Darwin for several years. Chronic ill-health, brought about partly by the anxiety of being known as the man who had killed God, kept Darwin in seclusion at Down House, his estate in rural Kent. Here he lived with his devoted wife Emma and their seven surviving children, sticking to a rigorous programme of thinking and writing unruffled by the flim-flam of scientific celebrity. A recent flare-up of his long-standing symptoms, which included vomiting and eczema, had given Darwin a gaunt, papery look that made him appear much older than his fifty-seven years. But, explained Emma Darwin, writing to her aunt Fanny Allen the day after the Royal Society event, it wasn’t so much the ravages of ill-health that had made Charles unrecognisable as his new beard – ‘it alters him so’.

Charles Darwin, beardless, four years before he published On the Origin of Species (c.1855)

You can see why the scientific establishment had been baffled. The last time anyone had set eyes on Charles Darwin he had been clean-shaven, apart from muttonchop sideboards. During the past four years of almost total withdrawal from public life he had grown a heavy beard that covered the lower half of his face and reached a good way down his chest. Instead of being ginger and springy like his earlier sideboards, this new instalment of facial hair was soft and white, which made him seem both ageless and ancient. It also made him look like someone else entirely. The features by which Darwin used to be most easily recognised – pouchy jowls and a long, thin, downturned mouth that readily rearranged itself into the sweetest smile – had vanished under a carpet of hair. Even his famously bulbous nose, which he always joked made him look like a farmer, seemed different somehow.

Darwin never trimmed his beard, although he did hack regularly at the hair on his upper lip to produce what his son Francis described as ‘a rather ugly appearance’. This habit of pruning his moustache too severely for elegance was a consequence of wanting to keep it out of his food at mealtimes. There was nothing he could do, though, about the stains left by his heavy snuff habit, which gave the middle part of the ’tache a dirty yellow look, colloquially described as ‘snuffy’. His hair, or at least the fringe that remained around the edges of his massive skull, was cut by Emma whenever Charles remembered to ask her.

By the time Charles Darwin had started growing his beard in 1862 he was already behind the times, as middle-aged gentlemen living in the country are apt to be when it comes to matters of fashion. In the 1830s and 40s, the decades of his young adulthood, the prevailing taste had been for clean-shaven faces. You have only to look at pictures of his near-contemporaries – Disraeli, Dickens, Ruskin – to see a series of girlish-looking young men, tender and rosy-skinned. But shift forward fifteen years, and each one of those lovely faces now lies buried under bristling facial hair. The first sign of a change in fashion had come in the late 1840s, when sideboards began creeping further down men’s faces, broadening out to the point where they became fully-fledged sidewhiskers. There were several ways of styling these new arrivals: broad but close-cropped attachments were known as ‘muttonchops’, while long, combed-out ones became ‘Piccadilly weepers’ or ‘Dundrearies’, after a dimwitted character in a play by Tom Taylor. Sidewhiskers could either be worn on an otherwise clean-shaven face, as Darwin did until he was fifty-three, or they might be teamed with a neat moustache, as modelled by that unlikely pin-up, Prince Albert.

Prince Albert in the 1840s

Gradually muttonchops and Piccadilly weepers crept further south, eventually meeting up under the chin sometime in the early 1850s. The result was the ‘Newgate frill’ or ‘chinstrap’, an odd arrangement whereby the neck and jaw were left riotously hairy while the rest of the face was clean-shaven. The effect was like a reverse halo, and was sported by Darwin’s younger friend and colleague, the botanist Joseph Hooker. Darwin, coming to beard-wearing a few years later, opted for the newly popular ‘natural’ beard. A natural beard required a man to do nothing more than leave his facial hair to grow untouched, give or take the occasional snip at the moustache with his wife’s scissors. This was also known as a ‘philosopher’s beard’, in homage to those thinkers of the Roman Republic such as Epictetus, Critolaus and Diogenes, who distinguished themselves from the smooth-shaven citizenry by their far-seeing wisdom and shaggy facial hair. Which explains why, aboard HMS Beagle in the 1830s, the young, temporarily bearded Charles Darwin had earned the nickname ‘Philos’.

Yet just because everyone else was growing a beard by the 1860s, it didn’t mean that Darwin found it easy or natural to follow suit. When the time came to announce that he had belatedly succumbed to the new fashion, he sent Hooker advance warning in the form of a photograph. In June 1864 the eldest Darwin boy, William, had taken a picture of his newly shaggy father in the garden at Down House, and this was now despatched to the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, where Hooker was Director. A copy also went to Asa Gray at Harvard. Self-conscious about the change he was unveiling, Darwin described his new look in his covering letters with a metaphorical shrug as ‘venerable’. Hooker, sensing Darwin’s anxious embarrassment, responded enthusiastically by return of post, declaring that his newly bearded friend appeared exactly like the figure of Moses in the fresco on the walls of the House of Lords. In this kitsch Biblical scene by J.R. Herbert, a hugely bearded and elaborately mustachioed Moses – he appears to have waxed the ends for the occasion – carries down the Tablets of the Law to some slightly less hairy Israelites. Hooker’s compliment was a neat if oblique allusion to the way Darwin’s On the Origin of Species had, in the five years since its publication, become the secular equivalent of the Mosaic tablets, a textual key to Life itself. Funnily enough, said Darwin in his pleased reply to Hooker two days later, his sons had said exactly the same thing about him looking like Moses.

Joseph Hooker modelling a neck beard, or ‘Newgate frill’

Darwin’s decision to announce his new beard to Hooker and Gray by sending them a photograph is not quite as coy as it sounds. Victorian men of science, even those who knew each other well, frequently used this new technology to exchange portraits as a way of strengthening personal and professional bonds. On receiving the ‘venerable’ photograph, Hooker immediately asked if he could have a copy to send to George Thwaites, Superintendent of the botanical gardens at Peradeniya, Ceylon, and another for Daniel Oliver, Professor of Botany at University College, London, both of whom he knew would value an updated image of the author of On the Origin of Species.

Even so, you sense that Darwin, always thin-skinned, was worried about how this new beard would go down in his wider professional network. The half-joke about the beard being ‘venerable’ was his way of putting distance between himself and his startling new appendage. In the unlikely event that Hooker or Gray made fun of his altered appearance, Darwin would be able to brush off his hurt by presenting his beard less as an essential part of himself than a temporary prop, a joke beard almost. Of course neither man offered any such barb. Gray’s only slightly carping comment was that the beard aged Darwin, a point that was picked up by another disappointed recipient of the photograph who was startled to discover that the clean-shaven middle-aged scientist he was used to picturing had turned into an ‘elderly gentleman with a grey beard’.

Most important of all, though, Darwin was determined that Hooker should not run away with the idea that he had grown a beard because he thought it suited him, or because, heaven forbid, he was trying to look fashionable. He was doing it, he explained carefully, for the sake of his health. In the late spring of 1862 the facial eczema from which he had suffered all his adult life had flared up in a ‘violent’ attack, bubbling his face and swelling his lips. At the spas Darwin routinely visited in search of a cure for his repertoire of mysterious yet distressing symptoms, men suffering from skin conditions were routinely advised to grow a beard. This was both a way of hiding the disfigurement and of avoiding the further irritation that came with daily shaving. So that was what Darwin decided to do. Or rather, according to his carefully crafted version of events, it was what his wife Emma told him to do. On 4 July 1862, in a faux-casual postscript to a letter about the cross-pollination of wheat, Darwin announced to his eldest son William, ‘Mama says I am to wear a beard.’

Despite being careful to give the impression that he had had no choice in the matter, Darwin had every reason to welcome this chance to hide his face from the world. As a twenty-year-old Cambridge undergraduate he had been so self-conscious about his scaly skin and ‘bad’ blubber lips that he had been known to pull out of planned beetle-hunts with friends in order to sit alone in his rooms until he was fit to be seen in public. On one occasion he had even fled halfway through an expedition in North Wales on account of his blistered skin. And while some of his adolescent self-consciousness had lightened by middle age, his symptoms had not. As a clean-shaven adult he had, on occasions, been rendered ‘hardly recognisable’, according to Hooker, by a particularly bad flare-up of facial eczema, which turned his usually plump, mild face red and angry, so that he resembled an indignant cherub.

This would be unpleasant for anyone, but for a man who had long been convinced of his own ‘hideousness’ it was mortifying. Following his mother’s death when he was eight, Charles had been raised by his older sisters at the family home, The Mount, in Shrewsbury, ruled over by their forbidding physician father, Dr Robert Darwin. Loving and responsible though Marianne, Susan and Caroline Darwin were, the grief-felled teenage girls found it hard to give the little boy the unconditional love he now needed so badly. Instead, they expressed their affection as anxious caretakers are apt to do, by finding fault. Caroline became known as ‘the Governess’, Susan was ‘Granny’, and both of them kept up a drizzle of complaints about young Charley’s spelling, handwriting and, in Caroline’s case, his looks and personal hygiene. Absorbing the message that he was somehow unacceptable – was that why Mama had gone away so suddenly? – Darwin grew up believing that he was ‘painfully ugly’. His nose, he told a school friend, was ‘as big as your fist’, and for that reason he was careful never to be pictured in profile. As a lanky adolescent he hated his large feet, made even more conspicuous by bunions. And his habit of gulping down comfort wherever he could find it meant that he had taken to asking for second helpings at every meal, like a giant Oliver Twist. In fact, for a time it looked as though young Charley Darwin was on his way to becoming as fat as his grandfather, the poet, physician and early evolutionist Erasmus Darwin, who was a twenty-four-stone mountain of a man. Eaten up by self-consciousness, the plump, knobbly-footed teenager dashed through the backstreets of his native Shrewsbury between school and home in an attempt to avoid people’s pitying looks. Even as a twenty-nine-year-old man, one who had made a thrilling name for himself by sailing around the world on HMS Beagle, not to mention losing twenty pounds in the process, Darwin was terrified of asking his cousin Emma Wedgwood to marry him. She would, he was convinced, find him ‘repellently plain’.

When Charles Robert Darwin was born in 1809 it had been into the smooth-chinned world of Jane Austen. The men from the provincial gentry and professional classes amongst whom the Darwins and their Wedgwood cousins naturally took their place were nearly always clean-shaven. In scraping the whiskers from their chins each morning with well-tempered cast steel they announced themselves as inheritors of Enlightenment values: rational, civilised, the opposite of beasts. Darwin’s father and grandfather before him, both distinguished men of science, had shown their treble-chinned faces to the world, confident about meeting its gaze without need for concealment. An open face denoted an open mind; beards, by contrast, were for men with something to hide.

In these circumstances it was inevitable that a smooth face became not only philosophic, but fashionable too. George ‘Beau’ Brummel’s morning shaving ritual was deemed so instructive that the cream of London’s ton was invited to pull up a chair and watch. In an attempt to match his dandy friend, the Prince Regent kept his porcine face free from stubble, while the only time his father King George wore a beard was when he had disappeared temporarily into the land of the mad. Meanwhile, at the Darwins’ local workhouse in Shrewsbury, which went by the euphemistic name of ‘The House of Industry’, the poor were shaved once a week. This provision was designed less to bolster the inmates’ well-being than to return their faces to a state of order and legibility, in the hope that their minds and morals might follow suit.

All of which makes young Charles Darwin a highly unusual young man. For by the time he was twenty-seven he had grown and shaved off his beard multiple times. One of the few contexts in which it was acceptable for a late-Georgian gentleman to sport facial hair was while at sea. And Darwin, famously, had spent almost five years, from December 1831 to October 1836, on HMS Beagle, a ten-gun brig-sloop commissioned by the Admiralty to survey the coast of South America. Although his position as a self-funded ‘gentleman naturalist’ did not bind him formally to navy discipline, Darwin instinctively observed the service’s codes of conduct during his exposure to them. And those codes decreed that, while it was acceptable for officers to grow beards at sea, on shore they were obliged to shave. Mixing with the local elites, both native and European, the ten or so Beagle officers were expected to appear as smooth-skinned gentlemen when presenting their papers to the Consul, dining at the house of a British merchant, attending a concert, visiting a botanic garden, hunting with the local padre, and even on trips up-country to stay on a grandee’s coffee estate.

Robert FitzRoy, captain of the Beagle – a stickler for a clean shave

In the case of HMS Beagle, the obligation to keep up appearances was doubly pressing, for the captain of the ship was Robert FitzRoy, nephew to the late Foreign Secretary Lord Castlereagh, and well-known for being the most crashing snob. FitzRoy was also ‘an ardent disciple of Lavater’, and therefore keen on reading faces and skulls for signs of character. He had almost turned Darwin down for the post of ship’s naturalist simply because, as Darwin recalled in his autobiography, ‘he doubted whether anyone with my nose could possess sufficient energy and determination for the voyage’. An out-of-place beard might mean the young man being left behind for good.

Darwin must have started growing a beard soon after the Beagle set sail from Plymouth on 27 December 1831, for by the time the ship reached the Equator seven weeks later he was sufficiently bristly for the crew to be able to perform the symbolic shaving ritual that always marked a seaman’s first ‘crossing of the line’. Under the watchful eye of a makeshift ‘Neptune’ the sailors ‘lathered my face & mouth with pitch and paint, & scraped some of it off with a piece of roughened iron hoop’, before dunking the neophyte in a tub of water. Darwin found the whole business ‘disagreeable’, although he knew he had got off lightly. The thirty-one equatorial debutants who followed him had ‘dirty mixtures’ pushed into their mouths and rubbed on their faces, the kind of toxic rough-housing that would have played havoc with the gentleman naturalist’s tender skin, not to mention his delicate stomach (he had been throwing up non-stop since they left Plymouth). All the same, you do sense a certain muffled pride in Darwin’s reaction to this bit of ritual bonding. The young man who just a few years earlier had scuttled home to his elder sisters whenever the crudities of public school proved too much had managed to survive this symbolic first shave without fainting or having to lie down.

After spending the spring and early summer of 1832 surveying the crumpled coast around Rio de Janeiro, the Beagle headed south towards Montevideo. As the little ship nosed towards Terra virtually Incognita the tone on board stilled and chilled. The barometer was falling, the seas were restless, and on coming ashore it was clear that something had changed. All the comfortable props of civic stability – sun-dappled white churches, busy market places, discreet whores, weather as pleasant as an English garden on a hot summer’s day – were beginning to fall away. In their place came armed soldiers, empty shops, sullen women, sheets of driving rain. Sailing into Montevideo at the end of July, the Beaglers had been corralled into putting down an insurrection of local black troops, while in Baha Bahia a month later Darwin had the feeling he was being watched, and his passport was checked and double-checked by henchmen of the local warlord. Safely back on board ship and headed south again, the older hands started to tell end-of-the-earth stories about shipwrecks, savage Indians and – a particular favourite – cannibal banquets. FitzRoy wrote home to his sister that ‘I am again quitting the demi-civilised world and am returning to the barbarous regions of the south …’ Darwin, in turn, wrote to his sister: ‘Every one has put on cloth cloathes & preparing for still greater extremes our beards are all sprouting. – my face at present looks of about the same tint as a half washed chimney sweeper.’

A few weeks later this ‘sprouting’ facial hair has become ‘a great grisly beard’ that, Darwin reports happily, has transformed him into ‘a wild beast’. By the time the Beagle reached Tierra del Fuego in the last weeks of 1832, the beard was so long that the young man could see the end of it when clasped in his fist. This wasn’t simply a gratifying novelty, it was practical too. During his week-long treks inland in search of mammalian fossils, stranded seashells and soil samples, Darwin often found himself obliged to bivouac at high altitude. On these occasions a beard acted as a muffler in the freezing dawns – ‘I never knew how painful cold could be.’ All the same, this didn’t stop the tyro naturalist complaining that he was feeling increasingly odd and itchy, like a bear forced into wearing an overcoat. And yet, such is the short memory of young men that by the time the Beagle eventually rounded Cape Horn and was heading north towards the elegant port of Valparaíso, where Darwin was due to lodge with an old Salopian classmate, he was grumbling once more about the chore of being ‘obliged to shave & dress decently’.

In its cyclical comings and goings, Darwin’s beard marked his criss-crossing from British gentleman to common tar to wild beast, and all the way back again. Clean-shaven, he was an emissary of British civilisation, an educated man with a family name that rang bells and with no reason to hide his pleasantly pudgy face from the world. But with a beard baffling his features, the man with a face like a chimneysweep, or even a bear, became indistinguishable from the common tars who heaved HMS Beagle around the globe. The ease with which mild, bashful young Charley Darwin could slip into this other identity – dirty, beastly and resolutely male – was thrilling. Armed with a beard, pistols and a geological hammer, he fancied that he might be confused with a ‘grand barbarian’. That, after all, is what had happened to Captain Robert FitzRoy RN, he of the impeccable lineage and finicky manners, who on the one occasion he had neglected to shave had been mistaken for a pirate.

Beard-wearing, though, did more than mark a simple boundary between civilisation and savagery, a line in the sand on which everyone could agree. The coastal ports of South America, where the Beagle officers regularly came ashore to mingle with the local elites, comprised an ethnographic free-for-all. In Bahia, Santa Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, Montevideo, Maldonado, Santiago and Valparaíso you would find African slaves, Jewish tailors, German blacksmiths, Arab traders, free blacks, American architects, Scottish engineers, English merchants, Argentinian gauchos, Fuegian Indians, not forgetting that large group of nondescripts and crossbreeds who belonged everywhere and nowhere. Amidst this polyglot jabber a beard became a conspicuous cultural marker, a handy feature to grab on to when trying to place a man you had only just met.

In letters home to his sisters Darwin makes jokes about how, if he were to turn up in Shropshire right this minute, he would be mistaken for a ‘Solomon’ who might start to ‘sell the trinkets’ – playing on a series of associations between Orthodox Jews, long beards and itinerant peddling. On another occasion he relates an encounter with a Uruguayan tradesman who suspects him of being a ‘Mohammedan’ simply by virtue of his long beard and his habit of washing his face.

As the tradesman’s mishit neatly demonstrates, in this mongrel world a beard could never do more than hint at a stranger’s identity. Throughout the Beagle’s voyage, Darwin was increasingly confronted with evidence that physical appearances – not just clothes but the bodies that filled and shaped them – were as much a matter of culture as of nature. On board ship were three young Fuegian Indians who had been educated at Captain FitzRoy’s expense in London. FitzRoy had collected these specimens on an earlier voyage, and hoped that now, released back to their old communities, they would form the nucleus of a Christianising mission amongst their own people. Having spent a formative year learning their Bible at a schoolmaster’s house in Walthamstow, these three young people now dressed like Britons and spoke a pidgin version of English. They had proved a big hit during their time in London, and were even presented at court. Queen Adelaide, grieving the loss of her endless babies, had made a particular pet of plump, merry ten-year-old ‘Fuegia Basket’, to whom she gave a cast-off bonnet. In their new incarnations the Fuegians appeared to Darwin like respectable members of the servant classes: vain, touchy, not always quite honest, but still recognisably creatures of the civilised world.

Jemmy Button (left) after his return to Tierra del Fuego in 1834 and (right) during his time in London (1833)

Just how far the Fuegians on board the Beagle had travelled from their earlier selves became startlingly apparent in the closing days of 1832. On 17 December the ship had anchored at the Bay of Good Success, a densely forested inlet at the very bottom of the South American landmass. Captain Cook and Joseph Banks had made land here sixty years earlier, but since then few Europeans had set foot on shore. As the Beagle nosed into the bay, Darwin got his first sight of indigenous Fuegian Indians. They had gathered on a ‘wild peak overhanging the sea’, forming something between an advance guard and a welcoming party. When the ship came closer, the tall, naked men issued an ambiguous ‘loud sonorous shout’, part threat, part salute.

It was thrilling, like something straight out of the boys’ adventure stories young Charley Darwin had lapped up during his Shrewsbury days. Writing later to his second cousin William Fox he described the watchful Fuegians with a delicious shudder as ‘savage as the most curious person would desire’. The Fuegians were equally gripped by the encounter. As they clambered down from the headland to take a closer look at the Beaglers, it became clear that the tribesmen thought that two or three of the shorter naval officers in the landing party were actually women. The seamen’s pale skin – paler anyway than the Fuegians’ ‘dirty copper colour’ – marked them as belonging to the fairer sex. This was despite the fact that the ‘ladies’ all sported heavy beards.

Here was the first sign that the Fuegians understood facial hair differently from their visitors. Although the Anglicised Fuegians were noticeably embarrassed by the ‘poor wretches’ on shore who were giving such a bad first impression of their native culture, the indigenous Fuegians were equally appalled by the returning wanderers. On being introduced to ‘York Minster’, the oldest of the Anglicised Fuegians, the locals were deeply troubled by the young man’s rough chin. They ‘told him he ought to shave; yet he had not twenty dwarf hairs on his face, whilst we all wear our untrimmed beards’, chuckled Darwin. As far as the Fuegians were concerned, foreigners were welcome to wear their disreputable whiskers, even the ladies. But they themselves would continue to keep up standards by sticking to a smooth chin. As a parting shot, one of the older tribesmen yelled at York that he was ‘dirty, and ought to pull out his beard’.

The Beaglers’ next destination was a settlement a few miles along the coast at Woollya Cove, where FitzRoy planned to set up his Anglican mission under the direction of a strangely listless young man called Richard Matthews. Matthews, aided by the three returning Fuegians – as well as York Minster and Fuegia Basket there was a fifteen-year-old boy called ‘Jemmy Button’ – would attempt to teach the local natives cleanliness and Christ. Before the mission could get under way, though, the Beagle endured a week of terrifying storms – the worst, said FitzRoy, that he had ever known. Not until mid-January 1833 was a landing party able to make its way into the cove on four small boats and begin building the mission. After so much misery it was cheering to find that the soil was deep and good, and garden beds were quickly sown with potatoes, carrots, turnips and beans, much in the manner of a rectory kitchen garden. Darwin couldn’t help noticing, though, what ‘culpable folly & negligence’ marked the choice of items that had been sent out by the ladies of the Church Missionary Society to settle twenty-two-year-old Mr Matthews into his new life at the ends of the earth: wine glasses, tea trays, soup tureens, not forgetting a handsome mahogany dressing case in which to store his razor.

It soon became clear that the tribesmen of Woollya were not as biddable as those further north. True, there was community singing one night, in which the Fuegians joined enthusiastically if ‘ludicrously’ out of time. But things turned sour when York Minster insisted on yelling ‘Monkeys-dirty-fools-not-men’ at the Fuegians in an unmistakable tone of disgust, while one of the older tribesmen made an alarming pantomime of pretending to skin and chop up a man. They are ‘so bold Cannabals that one naturally prefers separate quarters’, confided a jittery Darwin to his journal, his head full of the shocking stories that had been circulating about the nightmares that awaited at the very edge of the world. Yet despite the distinct possibility that young Mr Matthews was being eyed up for the Fuegians’ cooking pot, Captain FitzRoy gave the orders for the Beagle’s crew to depart. They would return, he promised the young missionary, in several days’ time to see how the little band of Christian soldiers was getting on.

Almost immediately, life became unbearable for Matthews, who had ‘no peace by day and very little rest at night’, according to what Darwin heard later. The Fuegians swarmed into his wigwam, and requested everything they saw – ‘Yamershooner’: ‘Give me’ – and when he said no, they took it anyway. One group stayed outside, making a racket to stop Matthews sleeping, while others picked up rocks and threatened to kill him. The three Anglicised Fuegians from the Beagle made no attempt to help when yet another group held the missionary down and ‘teased him by pulling the hair of his face’. There was obviously something about the young man’s whiskers that the Fuegians found comical, even slightly obscene. When, as FitzRoy had promised, a party from the Beagle made its return on 6 February, Matthews was spotted running towards the boats, screaming. As he was pulled on board he gaspingly explained that just five minutes earlier his flock had been plucking out the hairs of his beard one by one, using mussel shells as pincers. ‘I think,’ wrote Darwin that night, ‘we returned just in time to save his life.’

Darwin’s observations on beards – his own and other people’s – were to take root in his thinking and writing over the next forty years. In the books and articles that issued from his study at Down House he would repeatedly test the line that ran between nature and culture, the given and the made. What did it mean, exactly, that the ‘savage’, ‘miserable’, ‘abject’ Fuegians, who seemed at times to be barely human, turned out to have all the prejudices of Home Counties aunts when it came to wispy chins? And why had the returning Fuegians, whom Darwin had been convinced would continue to live as civilised Britons, reverted to their ‘grievous’ ways within months of being repatriated? Thinking more generally, why was it the case that only men had the ability to grow facial hair – at least if you discounted the Fuegians’ assumption that white women routinely sported bushy beards? And to what extent was human hairiness evidence that, far from being crafted in the image of God (another enthusiastic beard-wearer, if you could believe the paintings), man was simply an animal that had found a way of walking on its hind legs?

II

Arriving back in Britain at the beginning of October 1836, Darwin lost no time in sifting through his harvest of plant and fossil specimens before forwarding them to specialists for identification. Especially important here was the material he had gathered from the Galápagos Islands, nineteen tiny volcanic specks of land straddling the Equator, stocked with species that were not found anywhere else in the world. Self-taught ornithologist John Gould got the bird samples, clergyman Leonard Jenyns the fish, while anatomist Richard Owen of the Royal College of Surgeons received the fossil mammals, amongst which were some extraordinary finds. Most spectacular were a rodent the size of a rhinoceros and an armadillo as big as an ox.

By the following March Darwin had moved into rooms at 36 Great Marlborough Street, just off Regent Street, where there was space for himself, his servant and the crates of self-addressed material from the voyage that continued to arrive at Woolwich docks. He spent his days preparing a series of descriptive accounts of his five-year expedition, including The Voyage of the Beagle and the multi-decker Zoology of the Voyage of HMS Beagle, to which Jenyns, Owen and Gould would contribute volumes. Although he had received a grant of £1,000 to defray publication costs, thanks to the generosity of the Chancellor of the Exchequer Thomas Spring Rice, this was the last time the twenty-eight-year-old would have to look for financial support from beyond his own family. As an academically disappointing teenager, he had been educated first for medicine (half-heartedly at Edinburgh University) and then for the Church (even more sluggishly at Cambridge), before his father finally acknowledged that Charles’s real talent lay elsewhere, in the natural sciences. Dr Darwin, who had grown wealthy from his secondary career as a genteel moneylender to Shropshire’s first families, now settled on his younger son sufficient capital to produce an annual income of £400. This was enough for a bachelor to get by on, as long as he didn’t develop a sudden mania for women or horses. By this single stroke of luck, Charles Darwin became that most enviable and slightly old-fashioned of creatures, a gentleman of independent means, free to follow his intellectual interests wherever they led.

Just as Darwin was clattering his crates into Great Marlborough Street, workmen digging in nearby Trafalgar Square stumbled across a cache of elephant and tiger fossils. In that jolting moment modern Britain felt both ancient and very strange. This sense that the world was out of joint was magnified a few weeks later when a young girl ascended the throne after 120 years of middle-aged male rule. A propitious moment, then, for Charles Darwin to embark on a programme of enquiry that would end by dislocating the foundations of existence.

It started in a humdrum enough way, with a series of cheap notebooks into which Darwin dashed down his thoughts on the topic of ‘transmutation’. This was the word he used to describe the snail-paced process by which plants and animals developed variations to suit their particular environment, eventually branching off to form entirely new species. Page after page of Philos’s notebook was filled with breathless jottings on pigs, lions, volcanoes, rhododendrons, mountains, pelicans, coral and greyhounds, as he worried away at the question of how animal and plant life had evolved over millennia to fit what he knew from both observation and reading was the earth’s continually shifting crust. Darwin’s grandfather Erasmus had made a start on the topic forty years earlier in his path-finding Zoonomia. The Frenchmen Lamarck and Cuvier had continued to work on the subject from different perspectives during the difficult years of the French Revolution. Now young Charles Darwin of Great Marlborough Street took up the baton, trying to design a model that would make sense of his Beagle samples, as well as account for the data he continued to harvest from the hedgerows and farmyards of Great Britain.

Over the next eighteen months Darwin spent what little free time he had from his cataloguing work letting his mind roam over the big questions. Within weeks of disembarking from the Beagle he had reached the conclusion that species operate without divine agency. In his own mind God was dead, even if it would take decades before he hinted as much to anyone outside his immediate circle. But in that case, what was the mechanism that drove transmutation? And where did that leave Man, who according to Christian teaching was God’s special creation, quite separate from the beasts of the field? From the spring of 1838 Darwin became a frequent visitor to the heated giraffe house at Regent’s Park Zoo, where he spent hours staring at its temporary resident, an orangutan called Jenny. Dressed in human clothes, sulking and skittish by turns, Jenny resembled nothing so much as a hairy, copper-coloured baby. Opening his new maroon notebook Darwin wrote: ‘Man in his arrogance thinks himself a great work worthy the interposition of a deity. More humble & I believe true to consider him created from animals.’

Although he liked to describe himself as a hermit, Darwin did allow himself to be tempted out during these months, especially to any social event that was likely to prove professionally useful. It was for this reason that he eventually agreed to serve as Secretary to the Geological Society, which brought him into frequent contact with Charles Lyell, Richard Owen and pretty much every scientific man who mattered. All the same, he was careful to muffle the direction in which his thoughts were tending. Over the previous two hundred years scientists and theologians had attempted to reconcile Christianity with the emerging evidence of the earth’s ancient history. According to this hybrid model of ‘natural theology’, God was a kind of celestial watchmaker: He made the universe and its laws, although not necessarily in the seven days described by Genesis, and then retired to view His work from a great distance.

Darwin’s growing conviction that even this theory gave God too much agency was likely to be painful to older men like Lyell, who was still hoping to reconcile his radical geology with his liberal Anglican faith. Meanwhile, Owen, although helpful in identifying the Beagle fossils, was increasingly likely to react furiously to any challenge to his belief that species were immutable, each one the result of a separate act of creation. How, Owen reasonably argued, could a jellyfish become an ox, or an amoeba an ostrich? More important, at this time of political upheaval – it was only five years since the Great Reform Act had extended the franchise to the urban middle classes – transmutation challenged the essential distinction between human and animal, and by analogy suggested that the boundaries that kept different races and classes of mankind apart might be a matter of custom rather than divine edict. Far from God carefully appointing men to particular stations, the social order might more accurately be conceived as an arbitrary free-for-all, with the winners – people like the Darwins, for instance – merely lucky, or at least canny, rather than especially deserving. No wonder Charley kept his mouth shut and his notebooks close.

One of the reasons Darwin had decided not to settle back home in Shrewsbury on his return from the Beagle was that it would require him to make a constant round of ‘visits to stupid people, who neither cared for me, nor I for them’. Afternoons that could have been spent over his microscope would be frittered away taking tea with his sisters’ friends. Yet although the stuffy rooms in Great Marlborough Street allowed him to pursue the autonomous, anonymous existence of an urban intellectual, there were still some social niceties that Charles Darwin Esq., late of The Mount, Shrewsbury, was obliged to observe. Getting his hair trimmed, for a start. By now Darwin’s various Beagle beards were a thing of the past. They had been replaced with wide ‘weepers’ and a clean chin, the standard look in late-1830s Britain for a man of the professional classes. A portrait from this time by George Richmond shows that Darwin’s light-brown hair was already scanty for a man who was not yet thirty (see plate 6). Still, by carefully brushing forward his fringe in the ‘Caesar’ style that had been fashionable two decades earlier, he could just about pass off his bulging forehead as evidence of a large brain rather than a receding hairline. Here was the early-Victorian equivalent of the comb-over, although whether Darwin’s hairdresser, William Willis of 19 Great Marlborough Street, sniggered or shrugged or even suggested the arrangement in the first place, we simply do not know.

Willis, who was forty-one, was originally from Huntingdonshire. He had been swept into London twenty years earlier on the tidal wave of migration that had deposited thousands of young people from the country into the crowded capital as combatants in the new urban struggle for existence. Arriving with his wife Elizabeth around 1818, he set up as a hairdresser in Brydges Street, just off fashionable Covent Garden, before moving west to larger premises in Great Marlborough Street. Aided in time by his sons Alfred and Charles, he got his living cutting the hair of the professional men who made their homes in the handsome streets that ran eastwards off Regent Street. The fact that Willis made a point of describing himself in trade directories as a ‘haircutter and perfumer’ rather than ‘barber’ suggests that he took care to present his establishment as a superior one. While he almost certainly shaved chins in addition to cutting hair, he probably forswore the teeth-pulling, minor surgery and drug-dispensing that had for centuries been associated with barbering of the rougher kind. Great Marlborough Street was a popular residential address for doctors – the proper sort, with clean hands and letters after their names – and it is unlikely that Willis would have chosen the location if he was planning to offer the pulling, hacking and blood-spilling associated with the red-and-white swirl of the barber’s pole.

Like any migrating countryman, William Willis brought his old skills and pastimes with him when he settled in London. Breeding pedigree dogs and fancy birds had long been a profitable sideline for urban barbers, since it required minimal space and capital. It drew too on a discerning eye and a feel for physical form. If you could tend a gentleman’s whiskers, or advise him on his bald patch, it was a short step to running your hands over a prize spaniel’s coat, or measuring the length of its tail with your eye.

Although Darwin had himself been born a countryman – it was only eleven years since his exasperated father had yelled at him for caring about nothing except shooting and dogs – he had been away from the loamy farmlands of Shropshire for a long time. Talking to men like Willis jogged his memory about the way forward-thinking landlords, including his own Uncle Jos Wedgwood in Staffordshire, cross-bred livestock to produce juicier, taller, woollier, stronger, milkier animals, which could be mated in turn to bring about a permanent swerve in the species. Here, thought Darwin, might be a useful analogy for what happened in a state of nature, where animals that were best adapted to their surroundings survived and bred, passing on their genetic advantage to their offspring. Cooped up in the ‘vile, smoky … prison’ that was London in high summer, Darwin harvested his country friends’ expertise on selective breeding. He quizzed his old college contemporary Thomas Eyton about his owls and pigs, while William Yarrell, a Fellow of the Zoological Society, was happy to explain his experiences of crossing established breeds with hybrids.