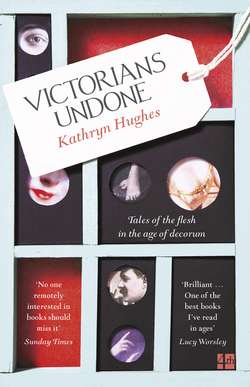

Читать книгу Victorians Undone: Tales of the Flesh in the Age of Decorum - Kathryn Hughes - Страница 8

Lady Flora’s Belly

ОглавлениеI

It is the last week of June 1839, and a young woman lies dying in Buckingham Palace. Outside, in the grand mansions of Mayfair and the long, sweltering sweep of Piccadilly, the Season is winding down, and anyone who is anyone is getting ready to leave London in search of stiff sea breezes and creamy country air. But thirty-three-year-old Lady Flora Hastings is adamant that she will not make the long trip home to the Scottish Lowlands for what will surely be her last few days on earth. It is important that she dies here, in central London, in view of the gawping public and the equally ravenous press. Lady Flora ‘remains much in the same state’, the Standard assures its anxious readers. Lady Flora ‘is still in extreme and undiminished danger’, explains the Morning Post, which has come to feel a proprietorial claim on this whole terrible business. ‘This unfortunate lady is, we fear, sinking rapidly to the grave,’ murmurs the Bradford Observer, as if it were standing by the patient’s bed on the first floor of the palace, taking her pulse. If the Observer actually had been present, it would not have liked what it saw. Lady Flora is as thin as a skeleton and almost as bald, a discarded rag doll rather than a soft, solid woman in her prime. Still, what you find your eyes drawn to again and again is not the patient’s once-elegant neck, now stretched like twisted rope, nor even her scalp, which is a rucked patchwork of bristle and skin. No, what you notice is her belly, which thrusts obscenely from her sparrow frame. In fact, if it did not seem so unlikely, you would swear that Lady Flora is about to give birth.

One floor up, the twenty-year-old virgin Queen of England sits writing her journal, as she does every night. It is, Victoria declares, ‘disagreeable and painful’ to have a dying person in her home. Just this week she has been obliged – although only after much ‘gulping’, according to one hostile witness – to cancel the end-of-Season ball she was planning in the Throne Room. Now that the novelty of Victoria’s fairy-tale first year on the throne has worn off, a smart quadrille is the only thing guaranteed to restore a rosy flush to that boiled-egg face. Sharp-eyed commentators can’t help noting a ‘bold and discontented’ tone to everything the young Queen does now. It was she who first started the rumour that the unmarried Lady Flora Hastings was, to use the polite equivocation, ‘enceinte’. Or if Victoria wasn’t the originator of the scandal, she was certainly quick to take it up, batting it around the middle-aged matrons in her retinue, searching their faces to see which bits of the story could be made to stick. And, although the doctors have more or less scotched the possibility, there is still an outside chance that at the very last moment Lady Flora, whether dying or not (and, frankly, the Queen has her doubts), will suddenly produce a baby from under her virgin skirts.

To understand ‘the Lady Flora Hastings affair’, a constitutional crisis that threatened to end Queen Victoria’s sixty-three-year reign almost before it had begun, you need to go back to 1834. It was in February that year that Lady Flora Hastings, then twenty-eight, sailed into court life under false colours. Officially she had been appointed as lady of the bedchamber to Victoria’s widowed mother, the Duchess of Kent, with whom the fourteen-year-old then-Princess lived in a suite of grubby rooms at Kensington Palace. But from all the muttered corner conversations and sliding glances it hadn’t taken the teenage heiress presumptive to the British throne long to work out that Mama’s new lady-in-waiting was actually intended as a companion for herself. The problem was that Victoria already had a confidante – her beloved governess Louise Lehzen, to whose firm care she had been entrusted at the age of five. Lehzen had been the Princess’s staunch ally in her struggles with the infamous ‘Kensington System’, that regime of isolation and control designed to ensure that when Victoria came to the throne at the age of seventeen or so (her ageing uncle William IV could not last much longer), she would appoint her mother as her Regent before retiring to the schoolroom for a further five years. That would allow time for the Kent coffers to refill, for the Duchess to entrench her Coburgian clan at court, and for Sir John Conroy, the Duchess’s Comptroller, to establish himself as the real power behind the throne.

Baroness (Louise) Lehzen

Yet for all its strenuous intentions, the Kensington System had proved unequal to its crooked task. According to Conroy, who had devised the elaborate set of rules by which young Victoria was to be shielded from any influence that might lessen her mother’s or his own, Lehzen had turned out to be a snake in the grass. Hiding in plain sight, as governesses are apt to, Lehzen ‘stole the child’s affections’ and set Victoria ‘against her mother’. The climax had come in 1835, when the sixteen-year-old heir to the throne refused to sign the papers that a desperate Conroy and the Duchess waved in front of her, the ones that promised to make them her Private Secretary and Regent the moment she became Queen. And in return for Lehzen’s steely support throughout all the shouting, slamming of doors and spraying of spittle, Victoria had funnelled towards her governess the affection that should, for safety’s sake, have been spread more evenly. When Lehzen’s name appears in Victoria’s nightly journal, it is spontaneously lavished with ‘dearest’ and ‘best’. The Duchess, meanwhile, is simply ‘Mama’, with an occasional limp ‘dear’ dutifully careted in as an afterthought.

The Duchess and her Comptroller had shuffled their plot to substitute Flora Hastings for Louise Lehzen behind a cover story about the latter’s unsuitability as companion to the young woman who could at any moment be called to be Queen. Lehzen might be known by the nominal title of ‘Baroness’, but that hardly qualified a Hanoverian pastor’s daughter who chomped caraway seeds (the Victorian equivalent of chewing gum) to provide the social gloss required to turn a German dumpling who muddled her ‘w’s and ‘v’s into an English Rose. Or, indeed, into ‘the Rose of England’, which is what some of the more gushing prints insisted on calling the heiress presumptive to the British throne. Dinner guests at Kensington Palace had started to whisper how unfortunate it was that Princess Victoria had yet to master the knack of eating with her mouth closed, especially given her habit of stuffing it so full of food that she resembled a small, pouched rodent. By contrast, Lady Flora’s table manners – indeed everything about her – were exemplary. The eldest daughter of the late Marquess of Hastings was known to be naturally pious yet sufficiently worldly to belong to what the newspapers liked to call ‘the Fashionables’. From the late 1820s you might spot the tall, slender young woman gliding around the supper room at Almack’s or attending one of Queen Adelaide’s Drawing Rooms (her brother was a gentleman of the bedchamber), her graceful figure and modish outfit warranting a short admiring paragraph in the gossipy Morning Post.

The Duchess of Kent and her daughter Princess Victoria, 1834

Within days of Lady Flora’s arrival at the Kensington court-in-waiting on 20 February 1834, fourteen-year-old Princess Victoria had protested in the only way available to her, by taking to her bed. Over the next six weeks she ran through her habitual repertoire of headaches, backache, sore throat, ‘biliousness’ and a fever, which not only got her the concentrated attention of ‘dear Lehzen’, who was ‘unceasing … in her attentions and care to me’, but also handily kept Mama’s new lady and her long neck at bay. Still, Lady Flora could not be dodged for ever. As summer gave way to autumn the Duchess made it clear that wherever Victoria and Lehzen went, Lady Flora was to go too, like an elegant hobble. The new lady of the bedchamber gamely trailed the inseparable girl and governess as they huffed up and down Hampstead Heath for the sake of the Princess’s convalescence, whiled away the holiday months in a series of grubby rented houses on the south coast, and sat through I Puritani at the opera for what seemed like the hundredth time. And it was here, in these awkward triangular huddles, that young Victoria had first grown to loathe Lady Flora as a ‘spie’ who snooped on her most private conversations, quarried her most intimate thoughts and bore them back in triumph to Conroy and Mama.

In the end, though, the Kensington System was bested simply by one silly old man living longer than anyone thought possible. By the time William IV, he of the pineapple-shaped head, died in the early hours of 20 June 1837, Victoria had passed her eighteenth birthday and was constitutionally entitled to reign alone. In those first thrilling days of power she tore through the old Kensington court like a tiny Tudor tyrant bent on restoring her favourites and casting her enemies into outer darkness (the Tower, sadly, being no longer an option). Lehzen was put in charge of running the royal household and became Victoria’s ‘Lady Attendant’, while the Duchess, angling for the title of ‘Queen Mother’, was told sharply that the thing was impossible. Lady Flora was left in no doubt either that her services as a companion to the new Queen were not required, although nothing could be done about the fact that she was still a member of the Duchess’s household, and would be moving with her employer to Buckingham Palace. Mercifully left behind in Kensington for good were the hateful Conroy girls, Victoire and Jane, whom Victoria had been forced to endure for years as unofficial maids of honour. Like the ugly sisters at the end of the pantomime, the beanpole pair now withdrew from the stage, and could henceforth be heard squawking loudly in the local shops about how much the new Queen still depended on dear Papa.

Just four years earlier Victoria had been playing with her dolls, a collection of 130 adult female figures named after celebrity aristocrats of the day and dressed to perfection by Lehzen’s clever needle. Now, in their place, the new Queen assembled twenty-six real, breathing women to be her daily companions. At the head of the new household was the fashionable Duchess of Sutherland, whose fairy-tale title was Mistress of the Robes. Other senior ladies included Lady Lansdowne (socially awkward but keen to please), Lady Portman (nice but dull) and Lady Tavistock (plain but tactful). The more junior maids of honour included Miss Pitt (beautiful), Miss Spring Rice (annoyingly friendly with Lady Flora), Miss Paget (‘coaxy’ and ‘wheedly’), not forgetting Miss Dillon, who was said to be ‘wild’ and required careful handling. Less glamorous in every way was Miss Mary Davys, the daughter of Victoria’s former tutor and chaplain Dr George Davys, who now became Resident Woman of the Bedchamber and was, noted Victoria in her journal, ‘a very nice girl (though not at all pretty)’.

With the exception of Mary Davys, ‘the ladies’ were drawn from the pool of great Whig families that furnished Lord Melbourne’s current government. Lady Tavistock was sister-in-law to Melbourne’s ally, the doll-sized Lord John Russell; Lady Lansdowne was married to the Lord President of the Council; while Lady Portman’s husband, newly ennobled, was doing sterling service in the Upper House. To wait on the young Queen was an extension of a political way of life that billowed out from Westminster to the grand Whig townhouses of Mayfair and from there to the rolling blue-green acres of Woburn, Chatsworth and Bowood. A confidence exchanged over dinner at Buckingham Palace might end up, a year later, back at Westminster, wrapped in a bit of new legislation or tossed away as a knowing joke.

On 17 July 1837 Mary Davys left her family home for this ‘dream of grandeur’, gusted along by a handsome salary of £400 a year. But although she was now hobnobbing with ‘the rank and fashion of London’, Mary soon discovered that the life of a courtier was no less mundane than life in a sedate vicarage. On receiving your ‘daily orders’ each morning, you might find yourself called upon to accompany the Queen on a walk, to church or on a visit to blind, elderly Princess Sophia, still mouldering away at Kensington Palace. Alternatively, there might be some kind of official business: a factory inspection, perhaps, or a visit to an orphanage, or one of the quarterly ‘Drawing Rooms’. But whatever the setting, the rules remained the same. You were required to walk far enough behind her little Majesty so as not to throw her into shadow (she wasn’t even five feet tall, although she insisted that she was still growing), but near enough to be useful if she needed to hand you something: a limp posy that had been offered by a none-too-clean fist perhaps, or a shawl that was now surplus to requirements. Indeed, ‘shawling’ was the name one wearied veteran gave to the whole fiddle-faddle of spending your days as a glorified lady’s maid, one who didn’t even get cast-offs and tips to compensate for all those hours lost to blank-eyed tedium and aching calves.

The evenings, too, could be numbing. Being placed next to the very deaf Duke of Wellington meant spending hours either shouting or being shouted at. Having Lord Palmerston – aka ‘Cupid’ – as your neighbour required you to shuffle your knees under the table to avoid his hopeful pokes and squeezes. And sitting next to one of Her Majesty’s more leaden cousins – Prince Augustus, say – involved racking your brains until you found a subject on which the young man from Saxe-Coburg would venture more than a single syllable. Dinner over, you might find yourself corralled into interminable games of ‘schilling’ whist with the Duchess of Kent, whose impenetrably Germanic English required you to strain to catch her drift. Finally, the teenage Queen, able for the first time in her life to determine her own bedtime, insisted on everyone staying up until past midnight, which meant that the larks in the company spent two hours stifling yawns and trying not to glance too obviously at the clock.

‘You must accustom yourself,’ Lady Ravensworth advised her daughter on her appointment as maid of honour in 1841, ‘to sit or stand for hours without any amusement save the resources of your own thoughts.’ But it was your own thoughts that were often the problem. As Mary Davys quickly discovered, the vacancy at the heart of court life quickly filled up with gossip, intrigue and petty drama from which it was impossible to remain aloof. The fact that the senior ladies were mustered on a rota, coming into waiting for only several months of the year, should have allowed for a regular freshening of the atmosphere. But in reality it never felt like that. Life at court was rather like attending a select girls’ boarding school where lessons had been temporarily suspended and some of the older pupils were breasting the menopause.

Take the business of nicknames. The habit of giving people aliases had begun during the last years at Kensington. John Conroy was known behind his back as ‘O’Hum’, and stage-whispered comments were made about his origins in ‘the bogs of Ireland’. O’Hum in turn had flung back remarks about Louise Lehzen’s table manners, making reference to ‘the hogs from Low Germany’. Other tags were ostensibly more benign, although you could never be quite sure, especially in a bilingual court where meanings and intentions quickly skidded. Flora Hastings had long been known as ‘Scotty’. Another of the Duchess’s attendants, Lady Mary Stopford, was ‘Stoppy’. Miss Spring Rice was ‘Springy’. Newcomer Mary found herself called ‘Humphry’ after the inventor of Davy’s safety lamp, designed to protect workers in enclosed spaces from suffocation and sudden combustion. Given Mary’s role as the royal household’s peacemaker and go-between, this sounds about right.

Yet despite her determination to resist the ‘too attractive, too fascinating’ lures of court life, Mary Davys found herself dragged into the household’s increasingly toxic churn. During the interminable drawing-room sessions after dinner the Duchess of Kent made a point of trying to pump her former chaplain’s daughter for information about what the Queen was thinking and doing. (Where once the Duchess had slept in the same room as her daughter and monitored her every waking moment, now she was crammed into pointedly poor accommodation at the other end of the palace, and only got to see her when there were other people present.) And although Mary resisted the Duchess’s fishing expeditions as tactfully as she knew how by keeping the conversation fixed firmly on such neutral topics as the novels of Sir Walter Scott, she could not help feeling sorry for the middle-aged woman in the too-bright silks who complained that she was now treated ‘as nothing’. Banished to the far end of the long dining table with Lady Flora Hastings, the Duchess could be heard sighing theatrically about how horrible it was to see Victoria’s ‘pretty young face’ next to Lord Melbourne’s old one, night after night.

Actually, the Duchess had a point. Spending up to six hours a day with her Prime Minister, including dinner most evenings, Victoria had started to hang on Melbourne’s every word, gulping down his thoughts on such pressing matters as how to spell ‘despatches’ and why women pack more for a short trip than men. More delightful still was the retrospective sympathy he offered over her struggles with the trifecta of Mama, Conroy and Lady Flora. The girl who had been brought up by her governess to give nothing away was, within a few weeks, telling Melbourne all about ‘very important and even to me painful things’, including what she insisted on describing as the ‘torments’ of her Kensington ‘imprisonment’. And he in turn, a middle-aged widower who had recently lost his only child, found himself enchanted with his confiding little mistress.

Lord Melbourne, c.1839

The political diarist Charles Greville, watching the new reign from his vantage point as Clerk of the Council, reckoned that the young Queen’s feelings for her Prime Minister were ‘sexual, though She does not know it’. What struck Greville was the greed with which Victoria lapped up Melbourne – not just his jokes and his thirty years of political knowledge and his remnant good looks, but his thrilling romantic history. For not only was Lord Melbourne the widower of the doomed Lady Caroline Lamb, who had gone mad with love for Lord Byron, but just the previous year he had been accused of ‘criminal conversation’ in the divorce trial of the notorious Mrs Caroline Norton. One of the founding intentions of the Kensington System had been to insulate the Princess from exactly this sort of dirty talk, which had been the lingua franca of her uncles George IV and William IV’s courts. A cordon sanitaire had been thrown around the girl, and no man was allowed to approach, unless he happened to be a cousin from the Continent. Indeed, one aristocratic lady visitor, arriving at Kensington Palace to take tea with the Duchess and the Princess, had been taken aback to be told that her six-year-old son would have to wait outside in the carriage.

‘Susannah and the Elders’ (1837), by John Doyle, shows Victoria flanked by Lords Melbourne and Palmerston

All of which made this sudden access to men, and stories about men, quite thrilling. It wasn’t just Lord Melbourne, although he remained the sun of Victoria’s solar system. It was also the gentlemen in her household, each dedicated to anticipating her needs before she had registered them as the merest flicker. There was Mr Charles Murray, who was master of the household; Colonel Cavendish, the equerry; and Sir Robert Otway, the groom-in-waiting. One young man, pretty Lord Alfred Paget, had taken chivalry to the most elaborate heights. The gallant young equerry kept a picture of the Queen in a locket around his throat, and made sure that his golden retriever, Mrs Bumps, was similarly attired. During the court’s periodic residences at Windsor all the gentlemen, including Lord Melbourne, wore ‘the Windsor Uniform’, an olden-days rig of breeches, buckles and cutaway coat with scarlet facings. It was like a fairy tale. It was a fairy tale.

II

If the Duchess of Kent appeared to have deflated to half her former size in the move to Buckingham Palace, her favourite lady-in-waiting had become more sharply defined. It was as if someone had outlined Lady Flora with a firm lead pencil: wherever you looked she was always there, ‘spying’ on the company and making her sharp little jokes. All of which was ironic when you considered that her status had tumbled along with her employer’s. At Kensington Flora had prided herself on keeping her desk as well-organised as ‘a Secretary of States’, as befitted a key member of the court-in-waiting. But with Victoria ascending to the throne on 20 June 1837 as a legal adult, Flora had been demoted overnight to the position of paid companion to the middle-aged widow of a minor Prince. Yet if she felt the humiliation, she said nothing. Instead she continued to behave as she always had: ‘restrained and uncommunicative’, according to Mary Davys, who was shaping up to be as good a ‘spie’ as Lady Flora herself. While the other court ladies popped in and out of each other’s sitting rooms to while away the endless hours with drawing, sewing, practising magic tricks and reading the Bible, Lady Flora made it quite clear that she was not open to such invitations: ‘we never think of going to her room’, explained Mary; ‘she does not wish it’.

At the end of April 1838 Lady Mary Stopford, about to finish her current period of waiting on the Duchess, was getting ready to hand over to Lady Flora, who had been away from court since the previous August. For the first time since their positions had been so dramatically reversed during the first few hours of the new reign, those two old foes, Baroness Lehzen and Lady Flora Hastings, would be obliged to live alongside each other once more. Lady Mary Stopford took advantage of a brisk carriage ride around Windsor Great Park to give Mary Davys ‘some hints about my conduct to Lady Flora Hastings, and said now was the time that I might by a little tact be useful to the Baroness and Queen whom she will try to annoy’. Twenty-two-year-old Mary, though, was not optimistic about her chances of neutralising ‘Scotty’s’ astringent reappearance at the palace. ‘The poor Baroness will be much plagued, I fear!’ wrote the worried clergyman’s daughter, ‘but we will hope for the best.’

Victoria, meanwhile, was not hoping for the best at all. On 18 April the young Queen confided to ‘Lord M’ how much she ‘regretted’ the fact that Lady Flora would soon be back in waiting, since she was, and always had been, the ‘Spie’ of her mother and Sir John. Lord M pronounced himself ‘sorry’ at the news too, and proceeded to pluck from his teeming memory a scurrilous account of Lady Flora’s antecedents. In response to the Queen’s pointed enquiry as to whether the late Marquess of Hastings had been a man of any talent, Lord M said emphatically not: ‘he could make a good pompous speech and gained a sort of public admiration’, but ‘“he was very unprincipled about money”’. Five days later, and with the ‘odious’ Lady Flora’s arrival now imminent, Victoria returned to the subject that had begun to obsess her: ‘I warned him against … [Lady Flora], as being an amazing Spy, who would repeat everything she heard, and that he better take care of what he said before her; he said: “I’ll take care”; and we both agreed it was a very disagreeable thing having her in the House. Spoke of J.C., &c.’

This segue in Victoria’s journal from Lady Flora to ‘JC’, trailed by that insinuating ‘et cetera’, was nothing new. During the Kensington years she had been forced to watch as Lady Flora and Sir John plotted ostentatiously in corners to get Lehzen – whom they snootily dubbed ‘the nursery governess’ – dismissed from Kensington Palace and bundled back to Hanover. But now, with that battle definitively lost, the fact that the conspirators were still spending so much time together was beginning to make people talk. Conroy’s constant presence at Buckingham Palace could be explained away by the fact that, while he had been dismissed from the Queen’s household (or rather, never appointed), he was still her mother’s Comptroller. To emphasise the point, he had taken to travelling every day from his Kensington mansion to the Duchess’s cramped suite in what was still referred to as the ‘new palace’, where he got under the feet of her visiting Coburg relatives and provoked some of Victoria’s more nimble ladies to dive for cover whenever they heard his booming voice on the stairs. There was, though, one room where he could always be sure of a warm welcome. Even Mary Davys, who tried so hard to keep her mind on ‘subjects of higher importance’, allowed herself to drop hints in her letters home. The real reason, she explained, why she would not think of knocking on Lady Flora’s door was because ‘I should be afraid of meeting Sir John who is there a good deal.’

Sir John Conroy, 1837

To those who wondered what on earth the stand-offish Scotswoman and the noisy Irishman had in common, it was doubtless pointed out by more sober-minded courtiers that, actually, their two families had been allies for decades. Conroy’s brother had been the Irish-born Marquess of Hastings’s aide de camp during his governorship of India from 1813 to 1823. The two men had bonded in adversity when both had been implicated in a banking scandal that had left their reputations in tatters – hence Lord Melbourne’s jibe about Hastings being ‘unprincipled about money’. In addition, Conroy’s anger at being let down by the Crown chimed with Flora’s own family mythology. Twenty years earlier her father had been left bankrupt after lending money to the Prince Regent. Lord Hastings’s final years had been spent trying to scrabble back his fortune by accepting the Governorship of Malta, a position that smacked of desperation for a man who had once been spoken of as a future Prime Minister.

So Lady Flora and Sir John had ample reason to bond over the way ingrate monarchs habitually swindled their most devoted public servants. In a letter written at the end of the first summer of the new reign, Conroy had spewed out his bile to Flora at how the Queen and Melbourne were currently batting away his claims to a peerage. Flattered by being taken into his confidence, the usually ‘uncommunicative’ Flora responded with what sounds remarkably like passion: ‘I feel that to know how deeply that letter touched me, you would require to see into my heart – I feel all its nobleness, all its generosity; of how kind in you thus to allow me to enter into your feelings to think me worthy of sharing them, to tell me I can be a comfort to you!’ Lady Flora is adamant that Conroy is ‘not treated as you deserve’, and that he ‘suffers for his integrity’. However, ‘these are days when the injustice of a court can influence only its own petty tribe of sycophants. You have met with much ingratitude & doubtless you will meet with more, but there are true hearts still left.’ Sir John, she concludes, is her ‘dearest friend’. From here her thoughts scramble to the fact that ‘in much you resemble my father. In much also your fate bears some analogy to his’, before finishing with ‘your reward is in Heaven’, which is probably not what Conroy was hoping to hear. At this point the usually ‘restrained’ lady of the bedchamber signs off to ‘my beloved friend’, calling herself simply ‘Flora’.

Around the time Lady Flora came back into waiting, Conroy unleashed the full blast of his anger towards Victoria for withholding the things that made his black heart beat faster: power, a peerage, a public stage on which to strut and bluster. By 11 June 1838, a fortnight before the coronation, to which he was pointedly not invited, Conroy had filed a charge of ‘criminal information’ against The Times. In effect he was suing the paper for claiming that he had siphoned off money from the Duchess of Kent’s bank account. Such was the tinderbox of bad feeling between the two households at the palace that Conroy suspected Victoria of having planted the piece herself. The list of witnesses to be called included Lord Melbourne, the Duchess of Kent and a jittery Baroness Lehzen, who had turned to jelly at the prospect of giving evidence at the Queen’s Bench. Which is exactly, of course, what Conroy had hoped for.

In the end none of the witnesses appeared. All the same, the Times business provided the nagging mood music to Victoria’s post-honeymoon period as Queen, a grinding reminder that the ‘torments’ of the Kensington years had not gone, but were waiting to bloom in strange new shapes. ‘I got such a letter from Ma., Oh! oh! such a letter!’ recorded a blazing Victoria in January 1838, reluctant to commit further details to paper, convinced that someone was reading her journal and blabbing its contents around the court. A few weeks later the Duchess attempted to patch things up by writing Lehzen a conciliatory note, but when that fell flat she retreated into her old nest of grievances, and added a few new ones for good measure. She complained that her ‘childish’ daughter was rude to her in front of other people and always took the opposite side in any argument. She put it about that Victoria had broken her heart, and paraded around déshabillée to prove the point. She spoiled Victoria’s nineteenth birthday that May by slyly presenting her with a copy of King Lear, and then sulked all the way through the anniversary ball. She believed John Conroy when he told her there was a plot to get rid of her, but couldn’t understand why Victoria continued to be so hostile to the man who was dragging the royal household through the courts. There had never, concurred Lord M, been a more foolish woman, not to mention a more untruthful one. Mind you, he added with a knowing look, the Duchess was fifty-two, which everyone knew was an ‘awkward’ age for a woman.

Nineteen was turning out to be tricky too. Victoria had danced through her first weeks on the throne as if this were the ‘happy ever after’ stage of a fairy tale, the proper reward for all those years as a Princess in the Tower (and there actually had been a tower in the grimy suite at Kensington Palace into which the Kent household had been crammed). Twenty-seven years earlier, in 1812, Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm had published their Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales). In these wildly popular stories, a copy of which was lodged on the bookshelves of the Kensington nursery, wicked stepmothers (actually mothers in the original version, before the Grimms felt obliged to soften the sting) were routinely vanquished, old crones turned out to be fairy godmothers, and missing fathers were restored to hearth and home.

Which is pretty much what had happened to Victoria during those magical first months on the throne: her estranged mother had been banished to a suite of rooms on another floor of the palace, Sir John Conroy and Lady Flora had been all but exiled from her court, and Lehzen had been given the keys to the household and installed in the next-door bedroom, as befitted her position as Victoria’s ‘dearest Mother’. Victoria herself had danced and dined and rode from dawn to dusk on her favourite horse with her adoring new father, Lord Melbourne, exactly as lucky young people in fairy tales are supposed to. Charles Greville, who combined a forensic eye with real psychological acuity, gave the best account of Victoria’s launch into pleasure:

Everything is new and delightful to her. She is surrounded with the most exciting and interesting enjoyments; her occupations, her pleasures, her business, her Court, all present an increasing round of gratifications … She has great animal spirits, and enters into the magnificent novelties of her position with the zest and curiosity of a child.

But now, a year into Victoria’s reign, it was becoming apparent that her life was not in fact culled from the pages of a fairy tale collected from the timeless forests of Westphalia. It was, rather, part of the grinding bureaucratic machine that was modern monarchical government. The despatch boxes arrived relentlessly several times a day, and however much Lord Melbourne put a hopeful gloss on things, the news did not always sound good. That May a violent uprising of farm labourers in Kent had gone further than anyone predicted. Canada was restless, split between the upper Protestant and lower Catholic territories. In Afghanistan the lives of British soldiers were at risk. Closer to home, Europe was threatening to break apart, despite everyone’s best intentions to keep faith with the geopolitical arrangements that had been hammered out at the Congress of Vienna twenty-three years earlier. Belgium was fighting to withstand the territorial bullying of the thuggish Netherlands, and Uncle Leopold was dropping crude hints that his niece should intervene to help the smaller country, over which he had ruled for the past seven years. Finally, and most worrying of all, Lord Melbourne was barely clinging to power. There had been crises in the autumn of 1837 and again in February 1838. At any moment, Lord M, Lord Palmerston, Lord John Russell and all the other kind Whig statesmen who took such a fatherly interest in Victoria might be out. And then she would be left alone. Even worse, she would be left alone with the detestable Tory Sir Robert Peel, that ‘cold odd man’ who, sniggered the Whig toffs, had all the camp charm of a provincial dancing master.

Even the delightful domestic routine that had buoyed Victoria through that first giddy year of being her own mistress was beginning to pall. The most ‘magnificent novelties’ could start to drag when repeated for the hundredth time. She had taken to snapping at everyone – not just Mama but even her ‘Angel’ Lehzen, ‘who I’m often cross to, when I’m ill-tempered, as I fear I often am!’ She was terrified that a maid she had recently dismissed would start spreading stories about just how awful her temper had become. With Lord Melbourne, too, Victoria was apt to sulk whenever he showed an inclination to spend the occasional evening away from her. But then, when he came scuttling back the next morning, she dropped hurtful hints about how boring it was to spend so much time with old people.

Victoria registered her unhappiness as she always did, through her body. Strictly speaking, she had two: public and personal. At the coronation in Westminster Abbey on 28 June 1838, it was Victoria’s public ceremonial body that had been symbolically rebirthed when the Archbishop of Canterbury consecrated her to her new life as monarch. The grandeur of this transformed existence had been captured by George Hayter, whose coronation portrait shows the young Queen sitting high on her massive gold throne (see plate 5). On her head rests the Imperial State Crown, while her right hand gravely grasps the stem of the Ceremonial Sceptre. The crosses on top of the sceptre and crown symbolise the sovereign’s temporal power under the Cross, while her feet rest on a bolster of English roses and lions. Victoria’s visible flesh, meanwhile, appears to have hardened into marble, so that she has, in effect, been turned into a metaphor made out of stone.

Every British monarch from the Middle Ages onwards had been obliged to negotiate the discrepancies between their public bodies and their ordinary mortal selves. Mostly they did this by employing portrait painters who slimmed down paunches, straightened out noses and festooned frail flesh with a lavish splatter of jewels and military decorations. When obliged to appear in person before the general public, they relied on extravagant artifice: at his coronation in 1821 the portly, middle-aged George IV (formerly Prince Regent) had been pulled in with corsets, puffed out with padding and wrenched into a shape that might just pass for a plausible king. In Victoria’s case, the gap between these two modes of existence was even more abrupt: set against the pomp and circumstance of the monarch’s public body, her biological femaleness and extreme youth felt like a glaring mistake. For every approving spectator who gushed that ‘the smallness of her person is quite forgotten in the majesty and gracefulness of her demeanour’ there was another who believed that the person who should really be occupying the throne was Victoria’s sixty-seven-year-old uncle Ernest, Duke of Cumberland and King of Hanover, a man who cut a handsome dash in full regalia (see plate 4). Indeed, it had been so as to see off the unpopular Ernest’s claims to be the most convincing – that is, male – heir to William IV that John Conroy had insisted on bustling Princess Victoria around the country in the years prior to the old King’s death. In a series of staged public appearances at factories, charity schools and regattas – ‘progresses’, an annoyed King William called them – the Princess had been presented to her future subjects as their next monarch, this insistence on her constitutional status as the first in line to the throne intended to blot out any lingering anxiety about that small, female body.

There was a further complication. It wasn’t simply that Victoria didn’t look like a Prince, it was that she didn’t look much like a Princess either. Her long torso and stumpy legs were a world away from the tall, slender, high-waisted aristocratic female ideal modelled by the 130 costume dolls that had been her constant companions during her later childhood and adolescence. Having reached menarche early, at twelve and a half, she had stopped growing before she was quite five feet tall. What’s more, her menstrual cramps and exhaustion, coded in her journal as ‘billiousness’ and ‘weakness’, had woven their way into her difficult life at Kensington, so that low, dragging belly pain became the recurring accompaniment to all the tension, all the shouting and the tears. And like any young woman who has been schooled not to express her emotions (Lehzen had always been very strict about that), Victoria had fallen into the habit of managing her feelings through food. Over the past few years she had swung between being fat and slim, according to whether she felt she was winning or losing the war against Mama, Conroy and Lady Flora.

All of which explains why, at the time of her succession, Victoria was looking her slenderest best, with a handspan waist of just twenty-two inches. No wonder that returning from his first meeting with the new Queen in the summer of 1837, the habitual old rake Lord Holland had declared himself ‘a bit of a lover’, finding her ‘in person, in face, & especially in eyes & complexion, a very nice girl & quite such as might tempt’. Yet the fact was that just a year later, no one was feeling particularly tempted by Victoria. After the early bloom of those first few months on the throne she was, suggested several commentators, reverting to her former fat and commonplace incarnation. Indeed, she now resembled nothing so much as a vulgar minor Duchess from an unpronounceable bit of Germany: those pouchy jowls, oyster eyes, and a chin that became a neck without you quite noticing how. In the summer of 1838, and increasingly feeling ‘cross’, Victoria developed a rash over her hands, while some months later one of her eyes sprouted a stye, which she insisted on showing to a repulsed Lord M. Meanwhile, her short upper lip, which her elder half-sister Feodora (so beautiful that men stopped and stared) had nagged about keeping over her teeth, was now permanently hitched to reveal sharp little rodent points. As a result she looked, in the words of one appalled maid of honour, like a caricature of the merry little rosebud of a Princess who until recently had so enchanted the nation.

Young Queen Victoria

Most upsetting of all was her figure. That twenty-two-inch waist had immediately started to swell, as if queenship required something more of her. In addition to eating too often and too fast, she had taken to gulping down prodigious amounts of alcohol at mealtimes, much to Mama’s and even Lord M’s alarm. All the ladies at court were obliged to change their clothes several times a day, matching their outfits to the demands of the moment: eating breakfast, waving at charity children, entertaining dull Coburgians after dinner. In such an intensely visual economy, where you presented a new version of yourself to the world every three hours or so, it was hard to hide even a modest change of shape. As Victoria started to puff out she increasingly opted for fitted bodices that showed off her excellent bust (Lord M said that a good bust mattered more than anything), and bell-shaped skirts under which she could smuggle extra poundage and the disproportionately stumpy legs that had long been the despair of her dancing mistress. But that autumn, passing through Paris, Lady Holland had heard a whisper from the Queen’s dressmaker that her clothes were having to be made larger than ever. Incontrovertible proof came in mid-December when Victoria stepped on the scales and found that she weighed nearly nine stone, which was ‘incredible for my size’.

Lord Melbourne did his best to try and jolly the Queen out of her physical and moral slump. What about eating only when hungry, he suggested. In that case, snapped the Queen, I would be eating all day long. Well, why not walk more, he asked. Victoria triumphantly fished out the example of Donna Maria of Portugal, exactly the same age as her, who walked all the time and still resembled a pudding. In any case, walking always meant getting stones in her shoes. Have them made tighter, came the mild prime ministerial reply. Melbourne also dropped hints about her personal hygiene, which had fallen off sharply. She really should try to change her clothes more often, something about which she admitted she had become ‘lazy’. And a bath taken in the early evening, before dinner, hinted the premier, might not go amiss.

Perhaps, though, looking like a caricature and smelling like a sweating horse was exactly the effect Victoria was after. Her early brief spell of prettiness had turned out to have its disadvantages, for it had not only attracted the attention of slobbering old roués like Lord Holland, but also stirred up the male population in the strangest ways. Earlier that year an admirer had managed to get access to the Chapel Royal, where he disrupted Morning Service by bowing, kissing and waving his hand to Victoria. Then there was Tom Flower, who was convinced that he was going to marry the Queen, and on one frightening night in July 1838 had managed to get within seven yards of her bedroom to tell her so. A few months later the infamous urchin Edward ‘the Boy’ Jones would live for a week in the back passages of Buckingham Palace before being apprehended with the Queen’s underwear stuffed down his trousers.

And then there was the endless heartless public chatter about which of her boy cousins she would marry – Hanoverian George, Coburgian Albert or Alexander from the House of Orange. For until Victoria’s body did what it was supposed to and produced a male heir, there was always the chance that the throne would be seized by her uncle the Duke of Cumberland, who, if Salic law had prevailed in Britain as it did in Hanover, would even now be ruling in her place. Yet none of Victoria’s suitors seemed to have the makings of a hero-prince in a Grimm fairy tale. They were plain, dull young men who blushed and stammered when they spoke to her, yet dared to imagine that they might one day lie alongside her in the marriage bed. Altogether more charming, although actually no less disturbing, was the way that ordinary Britons felt they owned the young Queen as if she were their personal pet. In the August of that second year some poor people left a kitten in a basket for her at Buckingham Palace. Next time, she was terrified that it would be a baby.

III

The culminating act of ‘the Lady Flora Hastings affair’ began in the darkest days of 1838. On 21 December Conroy won his case against The Times, and was overheard crowing that the Queen had been spotted coming in to dinner with red, swollen eyes. At the other end of the country Lady Flora was feeling queasy. She had been out of waiting since late August, and was spending Christmas with her family at Loudon Castle, near Kilmarnock, where she had been stricken with sickness and runny bowels. Her mother, the Dowager Lady Hastings, begged her eldest child not to return to London until her stomach had settled. But the sad news that Lady Mary Stopford was dying of consumption meant that Flora was urgently required to take her place. The Duchess of Kent, who was spending Christmas cooped up in that tatty fun palace Brighton Pavilion, with a daughter who barely acknowledged her, did not know how she would cope without at least one of her favourite ladies by her side. Flora, although hardly in a state to endure a four-day journey of deep winter ruts and uncertain privy stops, insisted on setting out for court the moment she was summoned, because she ‘could not bear to think of the D[uches]s’ being alone’.

What happened next has come down to us as so solid and certain, so much a matter of documented and established fact, that it has never been called into question. According to this habitual version of events, Sir John Conroy, happening to be in Scotland, arranged to share a chaise on the journey south with Lady Flora. But this turns out to be quite wrong. The mistake occurred because few biographers have looked at the Hastings family letters, including those written by Lady Flora, since they were read by the original recipients 180 years ago. That, in turn, is because the documents lie scattered in archives around the world, folded into other people’s lives. But if you extract and collate these various correspondences from the Huntington Library, the British Library, Balliol College Archives, Mount Stuart Archives, and the Flintshire Record Office, it becomes apparent that Lady Flora set out on 2 January 1839 quite alone in a private carriage, and in such a hurry that she was forced to travel for sixteen straight hours, without making her usual break near Doncaster to visit her cousin Lady Helena Cooke of Owston Hall. Sir John, who had indeed paid a brief visit to Loudon over the holiday period, was now tucked up safely at home in Kensington with his wife and family. The confusion arose because three months earlier, at the end of her previous period in waiting, Sir John had escorted Flora in a post-chaise from the palace to the Port of London, where she was due to embark on what was colloquially known as ‘the steamer’, or steamboat, for Edinburgh. Given that their friendship was already the ‘matter of joke and loose talk’, this was enough to set tongues clacking.

Why on earth had Flora Hastings risked ruining her reputation by travelling with a man to whom she was not related? Perhaps because, still unmarried at thirty-two, she considered herself such an old maid – her letters to family members are full of wry underlined phrases such as ‘at my years’ – that it would have seemed simpering to insist on a chaperone to protect her virtue while travelling with an old family friend such as Sir John. Then again, she may have considered that she did need a chaperone to make sure she was safely settled in her berth on the steamboat, and Sir John, a man she thought of as a second father, seemed an ideal protector of her maidenly virtue. A letter received by Conroy from the Dowager Marchioness Hastings on the day her daughter set off on her return journey south addresses him warmly, and thanks ‘you My Dear Sir John … & Lady Conroy, for all your kindness to My Dear Child & to say how I have felt all your attention’, before going on to explain just how unwell Flora has been over Christmas. Nor can we dismiss Lady Hastings as a provincial fussbudget far removed from court gossip: she makes a point of mentioning in her letter to Conroy how pleased she is that 1838 ‘closed with the Defeat of the Machinations’, a reference to his vanquishing of The Times. Lady Hastings then proceeds to drop a pointed hint that it is to the Duchess (no mention of the Queen) that Flora feels ‘a very sincere & grateful’ attachment.

After spending several nights with the Conroys in Kensington, on Thursday, 10 January Flora made the short hop back to Buckingham Palace, where the court had reconvened from Brighton. The Duchess was in a particularly jumpy mood, fretting about a new staircase that had materialised insultingly close to her own rooms. That same day a nauseous Lady Flora consulted Sir James Clark, physician to both the Duchess and the Queen. As well as feeling sick, she had a pain low in her left side, and her stomach was swollen. On Victoria this extra poundage could have been stowed away under one of her carefully contrived bell-shaped skirts, but on Lady Flora, who favoured dresses that clung closer to her slender frame, you really couldn’t miss the swell. In addition, her complexion was yellow, and most disturbing of all, one of her legs throbbed with shooting pains. Clark, a Scotsman long known to the Hastings family, examined the patient over her dress and wrote a prescription for rhubarb pills, a standard treatment for constipation, together with a camphor liniment to rub into her stomach.

This may have reassured Flora. Alternatively, if she knew anything of Clark’s diagnostic record, she had every reason to continue feeling very worried indeed. Victoria had recently made her doctor a baronet in recognition of the way he had stood up to Conroy’s ferocious bullying in the autumn of 1835, when the Irishman had hung over her sickbed while Mama and Lady Flora loomed in the background, pressuring her to sign a contract that promised to make him her Private Secretary once she became Queen. But when it came to doctoring rather than flunkydom, Clark had a comically bad track record. Put in charge of John Keats in Rome in 1821, he had breezily diagnosed the poet with stomach trouble, despite the fact that the young man was spurting blood from his consumptive lungs. And the year before that, Clark had reassured Victoria’s father, the Duke of Kent, that he was on the mend just as the fifty-two-year-old succumbed to a fatal chill brought on by damp stockings. Clark’s apologists claim that he told patients what they wanted to hear, because he grasped the beneficial effect of an optimistic mind on a fretful body. He also needed the fees: Sir James, the son of a butler, was a man who minded very much what he was paid.

Flora, writing to her uncle with controlled venom weeks later, maintained that at that first consultation Clark had been negligent, if not downright incompetent: ‘Unfortunately he either did not pay much attention to my ailments or did not quite understand them, for in spite of his medicines, the bile did not take its departure.’ Although Clark visited Flora’s room twice a week throughout January, he did little beyond patting her stomach through her clothes and pronouncing himself blandly satisfied with her progress, and made unfunny jokes about how she must be suffering from gout. So Flora briskly took matters into her own hands: ‘by dint of walking and porter I gained a little strength; and, as I did so, the swelling subsided to a very remarkable degree’. By mid-February her usually slender figure was getting back to normal, and she had been able to give away some dresses that no longer fitted. Heartily relieved, she even felt sunny enough to pass on to her sister a risqué remark from her Swiss maid, Caroline Reichenbach, about how m’Lady no longer resembled ‘une femme grosse’, or a pregnant woman.

If Lady Flora was not sure what was wrong with her, the Queen had no doubts. ‘Lady Flora had not been above 2 days in the house,’ recorded a flushed Victoria on 2 February, ‘before Lehzen and I discovered how exceedingly suspicious her figure looked, – more have since observed this, and we have no doubt that she is – to use the plain words – with child!! Clark cannot deny the suspicion; the horrid cause of all this is the Monster and demon Incarnate, whose name I forbear to mention but which is the 1st word of the 2nd line of this page.’ You didn’t have to be much of a code-breaker to work out that she was referring to Sir John Conroy. Counting back on their fingers, Victoria and Lehzen reckoned that it was four months since the Duchess of Kent’s Comptroller and lady of the bedchamber had travelled together in a post-chaise to the Port of London. Now the consequences were beginning to show.

Victoria lost no time passing on her suspicions to Lord Melbourne, and he at this point was happy to stir the pot. To the Queen’s fishing comment on 18 January that ‘Ma. disliked staying at home, and disliked and was afraid of Lady Flora’, Melbourne had replied provocatively, ‘In fact she is jealous of her.’ What’s more, recorded Victoria in her journal, Lord M had looked ‘sharply, as if he knew more than he liked to say; (which God knows! I do about Flo, and which others will know too by and by). “She tells him everything the Duchess does”, he said.’ There was no need to spell out who ‘him’ was.

The news of Lady Flora’s pregnancy now flashed through the ladies and gentlemen of the court, carried on stage whispers, arched eyebrows, slight nods and smirking glances, so that by the time the senior lady-in-waiting, Lady Tavistock, came back on duty at the end of January she found ‘the Ladies all in a hubbub’, with ‘strong suspicions of an unpleasant nature existing there with respect to Lady Flora Hastings’s state of health’. The ladies, reported Greville, who had got the story from Lord Tavistock, begged Lady Tavistock to ‘protect their purity from this contamination’. This might sound like fake outrage, mimsy posturing designed to keep the scandal bubbling away. But behind the ladies’ flutter lay a genuine terror that their good names were about to go down with Lady Flora’s. Over the previous thirty years the English court had gained a reputation as a moral pigsty, with the Queen’s uncles George IV and William IV appearing to live permanently inside a Gillray cartoon, one in which pink-cheeked buffoons with crowns askew spent their days frolicking with their fat-bottomed mistresses in a puddle of drink. There was even a laboured joke doing the rounds about how you would search the court in vain to find a ‘maid of honour’. The arrival of a young virgin Queen in 1837 was meant to signal a fresh start, a new broom. Yet now it looked as though Victoria’s household was no more chaste than its predecessors, putting at risk the reputations of all those virtuous matrons and respectable girls who had been so recently recruited as shawlers-in-chief.

Since Victoria was, by her own admission, not ‘on good terms’ with her mother – a damning detail in itself, as far as watching moralists were concerned – Lady Tavistock rejected the obvious step of approaching the Duchess about Lady Flora’s swelling belly, and went to Lord Melbourne, an old friend, instead. Lord M responded with his habitual advice of wait and see. Privately, though, he must have been spooked, for he sent immediately for Dr Clark, a man for whom he had never much cared. Clark, with his handy knack of telling people what he thought they wanted to hear, agreed with Melbourne that Lady Flora’s figure looked ‘suspicious’, although she had given ‘other reasons’ for her odd shape – probably constipation. But the doctor admitted he was sceptical, for if Lady Flora’s guts were really so disordered, how then was she able to ‘perform her usual duties with apparent little inconvenience to herself’? Clark’s implication was clear: having evidently struggled through the puking, hollow-cheeked first trimester, Lady Flora was now showing the blooming health of someone in flourishing mid-term.

When Melbourne passed all this on to the nineteen-year-old Queen at dinner on 2 February, he found her primed to explode with vicious glee: ‘when they are bad, how disgracefully and disgustingly servile and low women are!!’ But such sententious self-pleasuring was exactly the kind of thing guaranteed to send Melbourne skittering crab-wise. It was impossible, he cautioned, for any doctor to be absolutely sure about a pregnancy, and as for women, they ‘often suspect when it isn’t so’. In fact, said the Prime Minister, trying to sound like a statesman rather than the old court tabby cat his political enemies sneered he had become, ‘The only way is to be quiet, and watch it’ – by which he meant that, given time, Lady Flora would either produce a baby or not, and the matter would be decided once and for all.

More than anything, Melbourne wanted to contain this petticoat frenzy, so that should a pregnant Lady Flora ‘wish to go’ quietly from Buckingham Palace to some country cottage for her confinement, it would be easily managed without firing up a scandal. Lord Melbourne was a man of the Regency. He was himself rumoured to be the result of an affair between his spectacularly promiscuous mother and one of her many aristocratic lovers. He cared not a jot whether Lady Flora was pregnant or not, although on balance he thought she probably was. These things happened all the time, and in the best families too. Especially in the best families, in fact. All that mattered was making sure the growing scandal did not rebound on his mistress, whose own disordered domestic life was beginning to make a stir. Newspapers, especially of the Tory persuasion, were quick to hint that the little Queen had thrown over her mother’s authority and was now to be found cavorting in a seraglio presided over by that slack old whoremaster William Lamb, better known as Lord Melbourne.

Far from calming things down, Lord Melbourne’s policy of laissez-faire only tightened the tension as everyone tried not to stare too obviously at Lady Flora Hastings’s mysteriously shifting shape. Baroness Lehzen, usually so flinty, retired to her bed with a migraine. Sir James meanwhile started to badger Lady Flora on his regular stomach-patting visits with the uncouth suggestion that he be allowed to examine her with her stays removed. Lady Flora had recently had some new corsetry made to take account of her changing shape, and the doctor clearly believed that she was trying to bamboozle him with the oldest trick in the book. Offended by Clark’s insinuation, Flora rejected the suggestion immediately. This act of impertinence swiftly got back to the Queen, who responded by sending Lady Portman, her favourite lady-in-waiting, to instruct Sir James that he was to confront Lady Flora with the suspicions against her. When it came to phrasing the charge, Lady Portman suggested that Clark should follow a formula devised by Baroness Lehzen. He was to ask Lady Flora whether she was ‘privately married’.

There are several versions of what happened next. Some of these accounts were constructed as cross-armed defences, some as finger-jabbing prosecutions; all were written out of panicky self-interest. However, what everyone agrees is that on 16 February Sir James Clark went to Lady Flora and challenged her with the obscure possibility that she must be ‘privately married’. Sir James always maintained that he had been polite and tactful; Lady Flora insisted that his demeanour was so wild, especially the way he barged in without waiting to be announced by a servant, that she thought he must be ‘out of his mind’. Setting the question of Sir James’s manners to one side, Lady Flora realised at once that the phrase ‘privately married’ was a weasel way of accusing her of carrying a bastard child. Furiously rejecting the charge, she told Sir James that she had recently had a period – in itself a huge and indelicate admission for a lady to make to her physician – and pointed out icily that, had he been taking notice, he would have spotted that she had actually been getting thinner recently. As evidence, she pointed to the fact that she had been obliged to have some of her dresses taken in.

At this, according to Lady Flora, Sir James started to behave like the ship’s surgeon he had once been. He became ‘coarse’ and ‘excited’, declaring, ‘You seem to me to grow larger every day, and so the ladies think.’ He urged her ‘to confess’, as ‘the only thing to save me!’ When the indignant woman refused, the doctor slammed back that nothing but ‘a medical examination could satisfy’ the court ladies, or remove the stigma from her name. At the urging of Lady Portman, whom Clark now preeningly referred to as his ‘confidante’, this needed to be done quickly, since news of the scandal had ‘reached’ the Queen.

This last bit was nonsense, of course. The Queen had actually been the first person to spot Flora’s jutting belly, as far back as 12 January, and had sent Lehzen bustling round the court spreading the news. Far from being hazy about the facts of life, few unmarried girls were more aware of the practicalities of pregnancy than Victoria. For her own jolting journey to the throne had rested entirely on the chancy mechanics of human reproduction in general, and the gynaecological frailty of women’s bodies in particular. Born Princess Alexandrina Victoria of Kent in 1819, she had been placed fifth in succession, such an irrelevant outlier that not one British newspaper bothered to announce her arrival. Only gradually, as her ageing uncles failed to produce viable heirs, did the little girl at Kensington Palace start to inch towards the throne. Even then there was always a good chance that she would be stopped in her tracks by the late arrival of a baby cousin. In 1835, just two years before Victoria passed the finishing line, it looked as though King William’s wife, forty-two-year-old Adelaide, might be pregnant again after years of miscarriages, stillbirths and wheezing infants who gave up the ghost after only a few months. ‘What do you think of the Queen’s “grossesse”?’ wrote a gleeful Princess Lieven, wife of the former Russian Ambassador and inveterate gossip, to her confidant Lord Grey, who had served as Prime Minister earlier in the decade. ‘It will lead to a most important event, and one entirely unexpected. I can well imagine the looks of all the people at the little Court of Kensington Palace.’ It turned out to be a false alarm, and ‘the little Court of Kensington’ was able to exhale, just as it had every time one of the scrapings from poor Queen Adelaide’s inhospitable womb had slipped from this world, leaving Princess Victoria of Kent her uncle’s primary heir once more.

Thus sixteen-year-old Princess Victoria had spent a good stretch of 1835 caught up in feverish speculation about whether her forty-two-year-old aunt was pregnant or merely developing middle-age spread. By the time she became Queen two years later, Victoria’s journal is full of sharp-eyed observations about the blooming appearance of the women around her. On 2 February 1839, the very day the Lady Flora scandal was breaking, Victoria recorded that ‘Mrs Hamilton was looking very handsome, but very large, and evidently not far from her lying-in.’ A few weeks earlier the girl regularly referred to in the papers as ‘our virgin Queen’ had conversed unblushingly with Lord Melbourne about the fact that his mother had suffered ‘one or two miscarriages’.

Posterity has found it difficult to countenance the idea of a young, unmarried Queen Victoria sizing up women’s bodies for evidence of their sexual lives. Indeed, when rakish Edward VII came to the throne in 1901 he was so appalled by the ‘precocious knowledge’ revealed in his mother’s letters during the Lady Flora business that he oversaw their immediate destruction, along with later material concerning her middle-aged affair with John Brown. Modern biographers too have been reluctant to contemplate the virgin Queen Victoria as a sex-mad teenager, perhaps because it spoils that moment in the fairy tale when the Princess in the Tower is finally rescued and initiated into married love by the arrival of her Prince Charming, Albert of Saxe-Coburg. Whatever the reason behind this desire to look away (something which, ironically, Victoria herself never did), it explains the longevity of that original error about Lady Flora and Conroy travelling together in January 1839, rather than September 1838. Cutting and pasting the later date into each subsequent retelling has allowed Posterity to shake its head fondly over those two foolish virgins, Queen Victoria and Baroness Lehzen, who apparently believed it was possible to be spread-legged on your back in a jolting chaise in early January and sporting a pregnant belly just two weeks later.

Nor was it the case, as some purse-lipped observers maintained at the time, that Lord Melbourne’s racy table talk was to blame for opening the virgin Queen’s eyes to the sex lives of the men and women of the upper classes. Although Mama had always made a great show of protecting her from the disreputable court of Uncle William and his ‘bâtards’, Victoria knew perfectly well – well enough to joke about it – that her rackety paternal Hanoverian relations had nothing on her maternal Coburgian line when it came to casual copulation. Pedantic Uncle Leopold, he of the excruciatingly pompous letters, had arrived in Britain to marry Princess Charlotte in 1817 all poxy with the lover’s disease. Over in Schleswig-Holstein, Uncle Ernest and Aunt Louise, parents to cousins Ernest and Albert, had divorced following their double adultery. And Mama herself was rumoured to have had lovers outside her two short-lived marriages, the most recent of whom was supposedly none other than John Conroy.

Indeed, as far as the smart money went, the reason Princess Victoria grew up hating her mother and Conroy had less to do with their bullying ambition to rule on her behalf, than with the fact they were sleeping together. According to the Duke of Wellington, speaking to Charles Greville, in 1829 ten-year-old Princess Victoria had ‘witnessed some familiarities’ between her mother and Sir John. When Greville quizzed the Duke as to whether by ‘familiarities’ he meant that the Duchess and her Comptroller were actually lovers, the Duke responded with a shrug that ‘he supposed so’. The matter hadn’t ended there, according to Greville, whose post as Clerk of the Council gave him access to all the best gossip of the day. The ten-year-old girl had blurted out what she had seen to Baroness Spaeth, a veteran lady-in-waiting and Lehzen’s best friend. Spaeth then took it upon herself to remonstrate with the Duchess, counting on the fact that their twenty-five-year relationship gave her the right to counsel the younger woman. But she had miscalculated badly. Spaeth, whom the young Victoria adored, was promptly banished to Germany, where she served out her retirement in the service of Feodora, Victoria’s half-sister, who was now installed in a draughty Schloss as Princess Ernst of Hohenlohe-Langenburg.

In court circles, the relationship between the Duchess and Conroy had long been a standing joke. Lord Camden liked to tell the story of how his little grandson, noticing the ‘assiduous attentions’ of Conroy to the Duchess, had blithely prattled that Sir John was ‘a sort of husband’ to her. Out of the mouths of babes. But while contemporaries, including Melbourne, were convinced that the Duchess and Conroy were lovers, historians have been less sure, suspecting the rumour to have been spread by Victoria’s uncle and heir presumptive, the resentful Duke of Cumberland, who doubled as the King of Hanover. All that matters, really, is that young Victoria, who ‘sees everything that passes’, according to the insightful Duchess of Northumberland, thought they might have been. Consequently she grew up with one eye fixed firmly on her mother’s waistline, waiting for the change of shape that would prove beyond any doubt that the ‘familiarities’ she had witnessed were no figment of her imagination. And when, in the course of 1838, Sir John Conroy turned his attention from the fifty-one-year-old Duchess to thirty-two-year-old Lady Flora, it was only natural that Victoria’s beady eye would follow suit, settling on the younger woman’s profile.

While teenage Victoria prided herself on being able to spot a pregnancy at fifty paces, she never ceased to be amazed at her mother’s myopia. Only recently the Duchess had caused embarrassed smirks and shocked glances when she had insisted on asking a very pregnant lady to ride with her. So it was to jolt her mother out of her habitual ‘mist’ that Victoria sent Lady Portman on 16 February down one floor to break the news that her unmarried lady of the bedchamber was suspected of expecting, and needed to submit to an examination to decide the matter. To drive the message home, Victoria condescended to visit her mother personally that same day, and later sent a message that Lady Flora should consider herself banned from court until she had proved that she was not ‘in the family way’.

The Duchess was ‘horror-struck’ by these revelations, noted a pleased Victoria. But she did not, according to Lady Flora, believe them: ‘my beloved mistress, who never for one moment doubted me, told them she knew me and my principles, and my family, too well to listen to such a charge’. And indeed throughout the crisis the Duchess never allowed resentment of Conroy’s waning sexual interest in her to infect her great fondness for her lady-in-waiting, whatever Lord Melbourne liked to suggest. The idea of the proposed examination appalled the Duchess as ‘an humiliation’, and she had no doubt, as she explained in a letter to Flora’s mother, that ‘this attack, my dear Lady Hastings, was levelled at me through your innocent child’. To show her solidarity with Lady Flora, she refused to attend dinner that night without her. When later that same evening Miss Spring Rice, the Queen’s maid of honour, asked permission to pop down to see how Lady Flora was feeling, Lady Portman stepped in to enforce the cordon sanitaire that now surrounded the disgraced lady-in-waiting. In the end Miss Rice was obliged to resort to posting a tupenny letter by Royal Mail as the only way of being certain to get a message to Flora at the other end of the palace. Infuriated by ‘Springy’s’ show of divided loyalties, yet relishing every second of the escalating melodrama, Victoria asked Lord M eagerly ‘if I didn’t look pale or red, as I had been so much agitated’. Desperate now to calm things down, Lord M assured her briskly that she did not.

Lady Flora’s immediate response to the accusation that she was pregnant by Sir John Conroy had been unfortunate to say the least. In an uncharacteristic panic and with her ‘brain bursting’, she had immediately taken a carriage to his Kensington mansion to ask what she should do. Conroy, who had spies everywhere, had assessed the situation already, and, spotting how ‘malice would distort’ her flight to his house, ordered her to return immediately to Buckingham Palace. Flora spent the evening in anxious talks with the Duchess, who begged her not to agree to an examination. The Duchess was convinced that Victoria’s real intention in demanding such a degrading procedure was to humiliate her, using the body of her lady of the bedchamber as a proxy.

But by the following afternoon, and having prayed for guidance, Flora Hastings had made the decision to submit to an examination as the ‘most instantaneous mode of refuting the calumny’. Her decision was prompted by the fact that a doctor whom she knew and trusted, Sir Charles Clarke, happened to be in the palace. Sir Charles was not only a specialist in female reproduction, he was physician to the weepy-skinned, red-eyed Dowager Queen Adelaide, whose touch-and-go obstetric history had propelled Victoria from obscure Princess to reigning monarch. Flora wanted Clarke to be present at the examination not simply because he was a friendly face, but because without him as a witness she knew that she would be vulnerable to Sir James Clark’s (no relation) need to prove himself correct in his diagnosis. With the Duchess of Kent still wailing about how cruel and unnecessary it all was, the lady of the bedchamber summoned the two doctors to her room.

It is at this point that the protagonists’ narratives start to veer wildly, so that what we are left with is a babble of jabbering voices, angry, scared, wheedling, desperate to save their own skins. In the account he published several months later, Sir James does his best to hand off the role of unfeeling, brutish physician to Sir Charles. According to Clark, Sir Charles gave Lady Flora one last chance to confess her pregnancy, since after the examination it would be ‘too late’. Refusing to do so, Lady Flora then requested that Lady Portman, whom she referred to as ‘my accuser’, should be called as a witness. On Lady Portman’s arrival, Lady Flora retired to her bedchamber with Caroline Reichenbach, her Swiss maid. At this point Sir James breaks off his story abruptly, as if he can’t quite bring himself to describe what happened during the forty-five minutes that followed. The next thing we hear is: ‘After Sir Charles Clarke had made an examination, he returned with me to the sitting room, and stated as the result that there could be no pregnancy; but at the same time he expressed a wish that I also should make an examination. This I first declined, stating it to be unnecessary; but, on his earnestly urging me to do so, I felt that a further refusal might be construed into a desire to shrink from a share of the responsibility and I accordingly yielded.’

Notice how Sir James carefully paints himself as a ‘shrinking’ creature, who has to be forced to ‘yield’ to the masterful demands of his more experienced colleague. He even claims unconvincingly that it had never crossed his mind that this was going to be a ‘medical examination’, by which he means an internal one. He had assumed, he maintains, that Lady Flora would be examined thoroughly through her clothing, probably with her stays removed. Just like the poor patient, he has been ambushed into the ‘ordeal’. However, according to the maid Caroline Reichenbach, swearing her account on oath on 23 July in the presence of an Ayrshire magistrate, Sir James’s behaviour during the examination was the exact reverse of what he had described: ‘while the whole demeanour of Sir Charles Clarke during the painful and humiliating scene was characterised by kindness, the conduct of Sir JAMES Clark, as well as that of Lady Portman, was unnecessarily abrupt, unfeeling, and indelicate’.

As Caroline recounts it, the little scene had indeed begun with Sir Charles gently suggesting to Lady Flora that if she were ‘guilty’, it would be better to admit it now, before the examination went ahead. Flora’s response was so emphatic and sincere that Sir Charles suggested that he was disposed to sign a certificate denying the pregnancy then and there. But at this point Sir James interrupted with, ‘If Lady Flora is so sure of her innocence, she can have no objection to what is proposed.’

And what was being proposed was indeed truly shocking.

In the nineteenth century most upper-class women – indeed most women – would reckon to get through life without exposing their ‘person’ to anyone except their husband and, perhaps, a midwife. Single women could avoid even this. Physicians, keen to distinguish themselves from their rougher surgeon colleagues, made a point of laying hands on a patient, especially a genteel one, as seldom as possible. As would-be gentlemen they asked forensic questions about symptoms, took careful notes and diagnosed from the other side of a heavy desk. Sometimes, to avoid any unpleasantness, the whole consultation was done by post. When on a rare occasion there was no way to avoid an internal examination, both the patient and the doctor were apt to find it a ‘blushing’ experience, and took every precaution to render it as impersonal as possible. One doctor insisted on the patient kneeling on a stool, facing away from him, while he fumbled under her skirts.

The arrival of new technologies in the 1830s and 40s should in theory have made the whole business of intimate physical examination less ‘blushing’. But in fact they served only to introduce a further note of obscenity. The speculum had come over from France in the 1830s, but its primary association with the examination of syphilitic prostitutes by police surgeons meant that it was hardly welcome in the genteel consulting rooms and well-heeled sickrooms of Great Britain. For, as the Lancet put it, while examination by speculum might be appropriate to ‘unsexed women’ already ‘dead to shame’, it constituted a shocking ‘immorality’ when imposed on virtuous women. Victoria herself was no friend either to physical examinations or to the technologies designed to depersonalise them. She thought the new-fangled stethoscope quite disgusting, and after her final confinement in 1857, refused any access to her doctors below the waist. It was not until attending her corpse more than forty years later that her last physician, Sir James Reid, discovered that she had for decades been suffering from a ventral hernia and a prolapsed womb.

As a specialist in women’s diseases, though, Sir Charles Clarke was impatient with such coyness. We know this because, by a stroke of archival luck, his lecture notes have survived. In these, delivered to an audience of junior doctors, Clarke gives a detailed account of the procedure formally called ‘examination per vaginam’, but which, he explains, is more earthily known as ‘the touch’. Briskly, he sets out the scenario to his young men: ‘You are called to a woman, that woman has got a vagina: you are called, having got a finger in your profession & that finger is to be introduced into the vagina.’ Then, in case the slower members of the audience have still not worked out what is to happen, Clarke helpfully summarises: ‘The whole operation consists in the introduction of the finger of the practitioner into the vagina of the woman.’