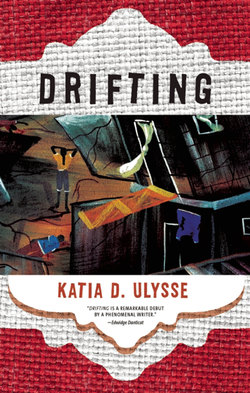

Читать книгу Drifting - Katia D. Ulysse - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSTRANGE FRUIT

Manman wrapped ripe sweetsop in the prettiest nightgown she owned. She tucked the bundle in a corner of her carry-on bag under the most delicate panties I’d ever seen. She would surprise Frisner with those: the fruit, the nightgown, and the panties. He would be grateful. He would wonder how in God’s name he survived without her for so long. How had he lived without her always thinking of him, always bringing him things like the only fruit in the world that had the power to melt his heart! Their happily-ever-after would resume with the first bite.

Manman had heard of people’s fruit being tossed out by customs inspectors on the other side, but was certain that no one would bother hers. The nightgown and delicate panties were parts of a brilliant strategy: no stranger with an ounce of decency would touch a woman’s underwear. Manman swore that her sweetsop would be as safe as a ja of gold buried under an unmarked tree in an orchard. No one would discover them. In a few hours, Frisner would taste all things past, present, and future in the succulent pulp.

My little sisters, Karine and Marjorie, daydreamed about the joys New York would bring: pretty dresses, new shoes, new ribbons for their hair, a doll like the one that disappeared from the upstairs bedroom. There would be candy by the ton. Life would be fun, fun, fun!

I daydreamed about what I would do once I reached New York too. I would find Yseult Joseph, my best friend, who was living there now. We would mend our friendship like the hem of a good dress that got caught in a thorn bush. We would patch the holes time created between us. We would be as close as we had been before she went away. We would be inseparable; this time forever.

I wrapped the six oslè I owned in a handkerchief and put them in the small purse that contained all the possessions Manman said I could take with me to the new country. Yseult and I would play oslè again.

Going to New York was like dying. We could not take most of our belongings with us.

On the night before we left, Manman gave away our dining table, the tablecloth, our dishes (even the good ones), our spoons, and every last grain of rice, sugar, and salt in the pantry. She gave away our pillows, the sheets on the bed, and the bed itself. Manman said we wouldn’t need those old things. She said we would have new lives and new possessions to go with them.

Manman could not wait to reach New York. She could not wait to see Frisner again. She’d petitioned the consul in Port-au-Prince for years, begging him to approve her application. “My children need their father,” she told him as tears leaked out of her eyes. She was overjoyed when the plane finally landed at JFK.

The worry lines that had been permanent fixtures on her face vanished. But when the cruel inspector at customs went through her carry-on bag and did the unthinkable, the lines instantly returned.

The inspector’s trained nose had gone straight to the corner of Manman’s bag where she’d hidden the sweetsop. He reached into the bag and removed her delicate panties—with a gloved pincer grip, as if they were soiled. He pulled Manman’s pretty nightgown out of the bag, shaking the silk away from his body as if it were an animal that needed to be quarantined. The sweetsop Manman attempted to smuggle rolled out onto the table and stared back at her. Her secret had been revealed. The inspector’s eyes accused her of an unspeakable crime. He did not ask questions. He did not have time to prosecute and punish her properly.

Dump the funny-looking crap and keep moving. There were thousands of bags to look through before his shift would end. Hundreds of strange fruit to throw into trash bins. “Next.” The inspector’s voice matched the fierce look in his eyes.

“Please, please,” Manman said, but what the man heard was “Tanpri souple. Pa jete sa yo.” Those words, like the fruit he’d gotten rid of, were foreign to him. They meant nothing.

Manman eyed the man and the garbage bin with equal disdain. Her joy had curdled. Something inside her had shifted. Something within her was now running and screaming like a child lost in dense woods. She’d made a mistake. Now that she was at the finish line, she realized that the race was fixed; she was bound to lose. Regret flooded her eyes when Frisner ran toward her with arms wide open.

Manman continued to cry when Frisner drove us to the colossal building that would become our new home. She cried when we walked out of the car and took an elevator for the first time in our lives. She cried when the elevator’s door slid open noisily and a corridor stretched out before us like a highway with carpet on it. The air smelled of thyme and rice pudding and cinnamon tea and burnt black beans and ginger cookies and strong coffee and beef stew with curry in it. Loud voices behind the black metal doors spoke languages I did not recognize. Manman continued to cry.

She cried as Frisner charged ahead and we followed him like ducklings. She cried as we walked past door after door after door on either side of the wide, carpeted highway. “Each door has a private home behind it,” Frisner offered. “Some have two, three, even four bedrooms.”

“Each one has a kitchen?” Karine’s voice bounced off the walls.

“Each one,” Frisner said without turning around. He would match our voices to our faces later.

“What about a latrine?” Marjorie had a pinched look on her face. She must have forgotten to relieve herself for days.

The excitement of going to New York had nearly consumed all of us. Karine could not bring herself to eat a bite of food; my own eyes refused to stay shut at night for more than a few minutes at a time.

“Where is the latrine?” Marjorie asked with even more urgency.

“Inside our apartment. Each apartment has its own toilet.” Frisner enunciated the word toilet carefully, letting us know that latrines—and all of their filthy, deep-in-the-woods connotations—belonged in the other world, not here. Frisner was careful not to call any of us by name. Perhaps he had forgotten them. Perhaps he could not recall Manman’s name either. Everything was chérie this and sweetheart that. Karine and Marjorie looked at each other and shrugged.

Frisner produced a large ring with a collection of keys on it. He jingled the keys theatrically in midair, telling us—without words—that only men of great importance could be trusted with so many keys.

“Welcome home, my love, my children!” Frisner’s face was arranged in a proud grin. But Manman missed both the “Welcome home” and the “my love” parts. The heartless man at the airport had thrown out a piece of her with the sweetsop. Both were now in a dump somewhere, rotting. Manman could not explain her loss to anyone, not to Frisner and certainly not to me.

* * *

When, after several months, the disappearance of Manman’s beloved tropical fruit still brought tears to her eyes, she opened her mouth and spat out the words that had simmered inside her all along: “I want to go back.”

“Kisa?” Frisner was incredulous. “You must be sick.”

“This country is for giants,” Manman explained with a desperate edge in her voice. “The buildings are too big. The streets are too wide. The stores are too bright. The lights are never off. The people never sleep. I feel like a grasshopper here. Vulnerable. An ant is what I feel like. I don’t belong in this place.”

The city intimidated Manman. The lights that were never turned off illuminated things she wished she did not have to see: ladies in neon shorts beckoning strangers and servicing them behind the bushes three stories below our living room window. But I needed those lights to shine eternally so I could find my friend Yseult Joseph.

Manman thought the artificially lit nights were terrifying. Back on the island, nighttime was as it was meant to be: dark. People became shadows at night, just as they were supposed to. Good shadows went home, bolted their doors, read the Bible, and slept. Bad shadows shed their skin, grew horns, tails, and hooves, and grazed like stray goats; they roamed city streets and the countryside, wreaking havoc until the soft blue light just before dawn. New York, Manman said, was supposed to be different. The people were supposed to be sophisticated. They were supposed to have a sense of occasion. They were supposed to sleep at night.

The click-clicking of high heels on the pavement below our window was terrifying. The ladies strutting like seagulls along the water’s edge, day and night, were worse than those demons that used to gather on rooftops to inventory the souls of homeless children in Port-au-Prince. The ladies kept Manman awake at night. New York was an unnatural place, she concluded, an open grave with dirt and snow piled high on either side. She wanted to fly back toward the familiar island sun and never return.

“I brought you out of there and now you want to go back!” Frisner was stunned. “If you leave New York . . . I swear . . .” He did not have to say the rest. If you leave now, we’re done, through, over, divorced. “You hated your life there,” he reminded her. “Have you forgotten how much you couldn’t wait to leave?”

“I was happy!” I could not believe Manman uttered those words. If anyone was happy in Haiti, it was me. Unhappiness came only when a certain someone made me read fifty thousand psalms when I was too tired to do anything but close my eyes and dream about Yseult Joseph. Until Yseult got on a plane and left me without a best friend, I was the happiest person on the island, wasn’t I? She used to come to my house every day after school. We’d eat mangoes and sweetsop until our stomachs ached. We kept our eyes on the doll in the upstairs room, and she never bothered us, did she? The doll was happy too, wasn’t she? Until she heard all that talk about us going to New York. It was only then that she left her cobweb-ridden high chair and was never seen again.

* * *

Frisner was supposed to quiver with joy upon meeting the girls he’d fathered but left behind for Manman to raise on her own. Reality in the form of indifference erased that thought and filled Manman’s mouth with a taste so sour that to this day she cannot help but be bitter.

He was nowhere near thrilled to rediscover the particulars of full-time fatherhood.

Taking care of himself hadn’t been so expensive and time-consuming. (A few kind women picked up the slack here and there—cooking warm meals, ironing sheets that didn’t need it.) Now, in addition to the landlord demanding to be paid, the grocer, the doctor, the dentist, and the pharmacist also wanted money. Even the washing machines at the laundromat didn’t care if there was only a nickel left to be split five ways. Feed me or wear filthy clothes, they hummed.

Frisner’s unexpected announcement came one payday after he counted the change that was left once all the bills were paid. “Children are like industrial-strength juicers,” he said. Manman listened quietly. “By the time they’re done with us, we won’t have any pulp left. But we could have a good life, if we sent them back. They’d be fine down there. They’re young. They’d go back to school. A year’s tuition costs less than what I spend on food in a single week. We could have a happy life, you and me. This country isn’t good for children anyway. Especially girls. What do you say, chérie?”

Manman was too stunned to answer right away. After a few minutes of deliberation she said, “Flora is the oldest. I suppose we could send her back.”

“On top of that,” Frisner went on contemptuously, unaware that Manman had made up her mind about what she would do, “there are laws in this country that dictate what we can and can’t do inside our own house. If you step out of line, your own children can crush you like the grasshopper you keep talking about. If they don’t feel like doing what you tell them, they can just pick up the phone and off to jail you go to eat your meals with rapists and murderers.”

Manman had heard rumors about American children having their parents arrested for setting them straight. “Not Haitian children,” Manman said. “My Karine and Marjorie would never.”

“Children are the real giants in this country,” Frisner half-joked. “They’re expensive as hell to keep. And they have rights! In Haiti you can erase them like mistakes on a sheet of paper. Do anything you want with them. It’s not like that here. You look at them wrong and an avalanche of trouble will tumble down on you. How many times, back on the island, did someone give away an unwanted child to a neighbor, a friend, a stranger? You could take a kid to the countryside and leave him there like a bag of old clothes. Who would care? There are so many abandoned kids on the island, who could count them all? Try any of that here. Try dropping them off somewhere and see what happens. Someone is always watching.” Frisner was laughing and slapping his knees.

Manman sucked her teeth. She was repulsed by his words, however true they were. “Karine and Marjorie would never hurt us,” she maintained.

“We could have a nice life here,” Frisner reiterated. “You and me.”

“If I stay, my girls stay with me.”

“You’ll regret it,” Frisner snapped.

He was no longer laughing. No longer listening. He did not hear the compromise: “Flora, on the other hand, would get along just fine without us. In fact, the sooner we send her back . . .”

“To hell with all this,” Frisner said, and slammed the door behind him.

He returned many hours later. A woman’s perfume was mingled up with the smell of engine grease embedded in his woolen jacket. The perfume filled every inch of the apartment, daring us to try and ignore it. Daring Manman to state the obvious: This is not Joie de Vivre. This is not my perfume.

Manman soon found a solution to Frisner’s problem (the high cost of raising a family) and hers (the click-clicking of the prostitutes’ heels on the pavement below our window). She took a factory job working from sundown to sunup. She would silence the ladies’ heels as well as Frisner’s pleas to toss her girls back to the island like unwanted catch into the sea.

Frisner now walked around the apartment with his head down all the time, sulking like a boy who could not find his favorite toy. Manman had traded him in for a job and was punching a time clock at the exact moment when they were supposed to slip into bed together. He took solace in endowing himself with the gift of prophecy. “You’re wrong,” he told Manman angrily one morning upon picking her up from the factory. “You’re very wrong: New York won’t crush me like some little grasshopper. But it will crush you. And it will make your daughters walk the streets, day and night. It will turn all of them into bouzen. Whores. Mark my words.”

“Not my Karine and Marjorie,” Manman fired back. “Those girls take after me. Flora has too much of your blood in her veins. She looks and acts just like you. If you say New York will turn her into a bouzen, who would I be to disagree?”