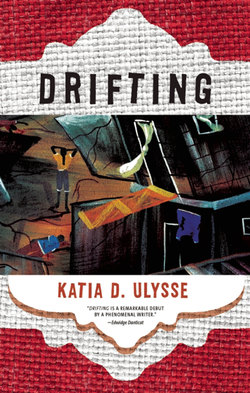

Читать книгу Drifting - Katia D. Ulysse - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFLORA DESORMEAU

Sister Bernadêtte doesn’t want me to sit next to Yseult, but she doesn’t want me near the other girls in class either. “You’ll contaminate them,” the nun says. I prefer to be near Yseult; she’s my right arm. She lets me copy the pages I need to memorize for the next day’s recitations.

“La Reine Anacaona fut enchaînée.” Yseult is standing in front of the class now, reciting her history homework. “Anacaona, the queen, was captured and taken to Santo Domingo. She was hung at the public square.”

“Very good,” Sister Bernadêtte says. “Very good” that the queen was captured and hung, or “Very good” that Yseult recited the lesson perfectly? Sister Bernadêtte smiles. The irony of it all: a citizen of the old mother country teaching Haitian children about history.

Yseult curtsies before returning to the seat next to me. I am not surprised when Sister Bernadêtte calls me next. I make my way to the front of the class and begin to recite the part about the Indiens being exterminated by a handful of Spaniards.

“When did the first blacks arrive in Haiti?” Sister Bernadêtte likes to try and confuse me. Her question has nothing to do with my recitation. And she knows I’m not good with dates.

“1503,” I tell her.

A mixture of disappointment and surprise flashes across her face. “Go to your seat,” she says in French. “And keep your mouth shut.”

“Keep your mouth shut,” someone mimics the nun.

“Who spoke?” Sister Bernadêtte wants to know.

“Yseult Joseph,” the other girls in class chorus.

Sister Bernadêtte is not convinced. “Flora Desormeau, what did you say?”

I shake my head. “Nothing.” I know what’s coming.

“Both of you,” the nun says to Yseult and me, “to the wall. On your knees. Now!”

“Dog shit,” Yseult mumbles under her breath, but I hear her clearly.

“Dog shit,” I mumble under my breath too.

“You two little piglets are disrupting my class!” Sister Bernadêtte shrieks, shaking menacing fists. “Face the wall, dumb mules. I don’t want to look at monkey faces anymore today.” The other girls in class cover their mouths as they laugh.

Sister Bernadêtte’s face is a fluffy pink pillow with big blue buttons for eyes. Her cheeks are red like the roses that grow around the grotto with the statue of the Virgin in it. Her lips are communion-wafer thin. Her large round eyeglasses make her head look like a full moon.

“Imbéciles,” she says. “Do not move until I tell you otherwise.”

Yseult and I have served this sentence countless times. Our knees are best friends with the cracked cement floor.

“C’est vraiment dégoûtant!” The nun’s French is so beautiful. It doesn’t even sound like she’s insulting us; her French is like a song—a fierce and passionate song overflowing with regret. Nostalgia.

“Imbéciles!” Yseult does her best imitation of the nun’s accent. My “C’est vraiment dégoûtant” doesn’t come close to sounding as pretty as Sister Bernadêtte’s.

Yseult and I practiced our French for years, but we’re nowhere near Sister Bernadêtte’s native-speaker timbre. The easy, unforced cadence will never dance off our tongues as it does hers.

The other girls in class, the ones who speak to their parents and their maids in French, they’ll sound like Sister Bernadêtte one day. Some of them already do. Not us. Yseult and I speak only Creole with each other and at home. Now, we gladly face the wall. The nun doesn’t realize that this punishment is sweeter to us than a hundred tito candy sticks rolled up into one. If she had any idea how much we loved it, she would think of something else. Of course, we never let on that we’re happy to stay on our knees for hours, watching the goings-on in the hotel below.

“Idiots!” The nun throws in one last insult in her pretty French.

Yseult and I look at each other and smile again. Now we have complete access to the tourists behind Cabane Choucoune’s tall wrought-iron gates. We are like angels watching over them, seeing everything they do.

Cabane Choucoune is exactly one hundred and twenty-six paces away from the school. But from our position in the classroom, it may as well be right below our window.

Even though the tourists never vary their routine, the scene around the pool is always worth Sister Bernadêtte’s wrath. When they’re not splashing around, the men-tourists stretch out under the sun until their backs turn boiled-lobster red. Then they flip over and do the same to their front sides. The women-tourists wear enormous hats and bathing suits emblazoned with giant sunflowers and ferns. There aren’t any children-tourists. Maybe tourists don’t like children.

Maybe children don’t like to be tourists. Even if they did, Manman says, Cabane Choucoune isn’t a place for kids.

The tourist-wives, in their enormous hats, sit at the edge of the pool, reading magazines and dipping painted toes into the sea-blue water. Sun-seared servers, in head-to-toe karabela accented with yards of multicolored ruffles, shuffle in and out of a revolving door. Each one balances a tray heaped with glasses that have little umbrellas in them (to keep the drinks from getting wet, should all that splashing around in the pool get out of control).

The little umbrellas are pretty, but the tourists pull them out of their glasses as soon as they snatch them off the servers’ trays. They destroy the pretty umbrellas while they sip their drinks. They break the tiny wooden poles, the ribs, and then they crush the colorful paper covers between their fingers.

The house where I live is fifty-three paces from Cabane Choucoune. I can see the sweetsop trees in our yard from Sister Bernadêtte’s classroom. Our house is a two-story A-frame with slender windows that have white shutters on either side. The floor creaks. Otherwise it is a very quiet house. The other place where we used to live was not quiet at all. We had to leave it after Papa went to New York. Manman could not live there with Papa gone. She said a bad spirit moved in the day he left. The bad spirit refused to let her sleep at night. It was in the air, under the floorboards, behind the walls, on the roof, but mostly inside Manman’s head.

Manman likes our new house better. The staircase that leads upstairs curves like a capital S. The banister looks like it belongs in a fairy tale. The wraparound porch is a good place to sit and watch hummingbirds flutter their wings as they feed on soft blossoms. The pantry is large enough for a flock of chickens, but only one lives in there. We bring her in at night from the yard. She gives us one egg every morning.

There are two bedrooms upstairs, but we occupy only one. The other stays locked all the time. The landlord says he lost the key to that door. We cannot open it. A doll lives in the locked bedroom. She sits in a high chair. Her hair glistens in the sunlight that streams in through a hole in the roof. Her lips are like a dried rosebud. Her face is pudgy, round, and pink like Sister Bernadêtte’s.

“You can almost see the doll room from here,” I whisper to Yseult.

“Shut up, little serpents!” the nun yells.

I wait for Sister Bernadêtte to choose another animal in her menagerie of insults, but she does not. Her jowls shake and she scrunches up her lips hard as if she’s trying to keep the words she’s not allowed to speak from slipping out. I turn my attention back to Cabane Choucoune. The tourists continue to bake themselves. The servers have fresh drinks on their trays. I try to count the little umbrellas. The tourists crush them even faster now.

When the bell rings, Sister Bernadêtte exhales loudly. “Good riddance, little bats.”

Yseult and I bolt out of the classroom like the African gazelles we read about in geography class.

Yvela is outside, as usual, waiting. She’s a few months older than Yseult and I, but looks much older. Yseult and I hold hands and skip down the street to my house. Our feet barely touch the ground. Yvela runs behind us.

Naturally, we stop by Cabane Choucoune and peep through the wrought-iron gate that separates the hotel from the rest of the island. The tourists are still baking themselves and dipping their toes in the sparkling water. The servers are still shuffling in and out of the revolving door with an assortment of drinks on their trays.

“One day,” Yseult says, “I’ll come to Cabane Choucoune and dip my toes in the pool too. I’ll sip drinks with umbrellas in them and have lots of fun too. One day I’ll wear a large hat and sunglasses that hide my eyes. One day I’ll wear a bathing suit with flowers on it too. One day after I become a famous artist . . . One day . . . Maybe after I go to New York and my paintings are in every gallery in the world and I become rich and beautiful like the tourist wives. One day.”

Yvela laughs and says, “Woy, pitit! You have a better chance of wearing that ruffled skirt and serving the tourists their drinks.”

“Close your stinky snout,” Yseult snaps, and Yvela’s face looks fifty years older. “When I grow up, I’ll be rich and beautiful. And I will come to Cabane Choucoune and do as I please. Yvela Germain, you’ll be the one wearing the servant’s skirt. You’ll be the one bringing me whatever I ask. You’ll be my personal rèstavèk—just like you are now.”

“What about Flora?” Yvela has a smirk on her face. Her young mistress could dream a great future for herself, but what would she predict for her friend? “What is Flora going to do while you’re busy being rich and beautiful and so on?”

“Flora is my best friend,” Yseult retorts. “We’ll be together. Always. Naturally, when I come to Cabane Choucoune, she’ll be with me.”

Yvela cups her hands over her rows of cracked, rust-colored teeth and giggles. “She’ll take my place then!”

I pretend not to hear. Yseult is a great artist. She sketches everything she sees and makes them look better than they are in real life. She’s sketched me a thousand times and managed to make me look presentable.

Yseult always says she will be a great artist one day; I believe her. As for me, I don’t know what I’ll be when I grow up. Maybe I’ll learn to make school uniforms and wedding gowns for ladies who don’t know how. Maybe I’ll die before I become anything. Who knows? But if Yseult tells me that we’ll come back to Cabane Choucoune together one day to be as carefree as the tourist-wives, then that’s exactly what will happen.

“Yseult Joseph,” Yvela screams, “let’s go before your manman sends the Tonton Macoutes after me.”

“Manman doesn’t care what time I get home anymore!” Yseult shouts back, taking my hand in hers. “Flora and I will play oslè for as long as we want. You can take me home afterward.”

Yvela scratches her head while mumbling something under her breath.

When we reach my house, we take off our shoes and sit on the porch. I press the soles of my feet against Yseult’s. There’s a diamond-shaped space between us. Our skirts are bunched up and tucked under our thighs.

Yseult throws the first round of oslè. We use real goat joints, not those slime-green plastic jacks that some of the girls whose mothers live in New York send them. She throws one of the oslè high above her head. “Un do,” she says and picks one up from the floor. “Deux do.” She picks up two. “Trois do . . .” She drops one of the oslè and grunts. It’s now my turn. “Yvela, fetch my things.”

Yvela brings Yseult her sketchbook and a pencil. Yseult stares at my face while her right hand moves swiftly on the paper. She shows me her creation a few moments later: my eyes now have a mountain range in them.

I can play oslè for hours without losing a turn. Yseult doesn’t mind. She can sketch for hours without stopping. She draws one of the mango trees with ripe fruit hanging from its limbs. “Yvela,” Yseult says, “get us a couple of good ones from that tree.”

Yvela scales the tree like a boy. Her scarred knees cling to the bark. Yseult sketches Yvela’s face and gives her the body of a zandolit—a lizard. Yvela’s grip is firm as she pulls herself higher and higher. “Come get them,” Yvela calls out.

Yseult and I run toward the tree to catch the fruit in our skirts, lest they fall on the ground and burst. When Yvela climbs back down, we sit together and eat until we’re full.

“Wait for me here,” Yseult tells Yvela.

“What else would I do?” Yvela sucks her teeth.

“Keep showing off,” Yseult says. “See if I don’t tell Manman. See if she doesn’t pull out what’s left of your brown teeth.”

Yvela makes the sign of the cross on her lips. “Pardon me,” she responds.

“I want to see,” Yseult says as she takes my hand. She wants to go upstairs every time she comes to my house after school, especially when Manman is not here.

“Where is she?” Yseult squints as she peeps through the keyhole. “Where is the doll?”

“I don’t know,” I tell her. I look through the keyhole too. The high chair is there, but the doll is not. “Stay with me.”

“I can’t,” Yseult answers quickly. Her eyes dart about. She runs down the stairs.

“I don’t want to be alone,” I tell her.

I have to go, she says without words. Just her eyes.

When we reach the porch, Yseult takes Yvela’s hand and runs away.

* * *

Madan Casseus watches me when Manman is away. She won’t get here until dark. I try not to think about the missing doll. I try not to think about anything at all.

Manman went to the leaves doctor’s compound again. She took Karine and Marjorie with her. Manman took me to the leaves doctor once, but the man said I was different from the other girls somehow and did not need special protection against bad spirits. (Manman is afraid the bad spirit might follow her to our new house. The leaves doctor concocts a special lotion that’s supposed to keep all bad spirits away.)

To get to the leaves doctor’s compound, you have to start walking before the sun even thinks about rising. Walk for a long time, past a cemetery teeming with stray goats and graves heaped with food and candle wax. Go through the marketplace where vendors haggle in a singsong that tells you you’re a long way from Port-au-Prince. Cross a valley full of bones that crumble under your feet. Pray that the scorpions scurrying on the blistering rocks don’t sting you. Walk some more until you see the statue of Fatima nestled in the shimmering mosaic grotto on the other side of a little stream. Cross the little stream, then stop. Stop at the grotto; everyone does. Kiss Fatima’s feet three times. Seven, if the line behind you isn’t too long. Then walk up a mountain that’s so high it takes hours to reach the top. When you do reach the top, sit down and rest awhile before starting down the other side. The leaves doctor’s compound is visible from that distance, but you won’t reach his front door until it’s so dark that you’ll think you’re blind. But you’re not blind because your eyes will catch the glow of a bald-headed lamp that’ll draw your shadow into the house long before you reach it. When Manman goes to the leaves doctor’s compound, she stays for several days so that he has plenty of time to do whatever it is she’s convinced he can do.

Since Madan Casseus won’t get here until after dark, I’ll wait for her on the porch. When I hear her donkey approaching, I’ll pretend to be asleep. She’ll shake my shoulders gently and tell me to come inside. Young girl, children mustn’t sit outside by themselves.

We’ll go inside. She’ll offer me some of the food that the taptap drivers did not buy from her. I’ll take some fried plantain and spicy blood pudding. Then Madan Casseus will make me take off my school uniform and iron the wrinkles out of it. She’ll make me wash my feet in the basin before going to bed. I’ll put on my nightgown while she bolts the front door. She’ll tell me to pray for my mother and sisters. “Priye pou Manman-w, pitit. Pray for them.” I’ll kneel down by the bed. Cross myself. Recite the Our Father. Madan Casseus will recite the Our Father along with me. “Good night,” she’ll say. “Dream about butterflies and rainbows.”

“Good night,” I’ll say. “Dream about butterflies and rainbows too.”

In the morning, Madan Casseus will saddle the donkey and ride down to Kalfou Djoumbala. She’ll spend the day there, selling food to famished taptap drivers and their passengers. I won’t see her again until after dark.

In the morning, I will wait for Yseult to stop by on her way to school. We’ll run together, hand in hand. Yvela will carry Yseult’s bags as she follows us. She’ll leave only after the nun locks the gate.

Yseult and I will stand one behind the other to pledge our undying love for our nation and her flag. We’ll throw our voices high when we sing our national anthem.

Yseult’s voice will sound pretty. Her French will sound better when it’s mixed up with the other girls’, the ones who speak it even when no one is listening. “Marchons unis! Marchons unis! In our midst there are no traitors . . .”

Afterward, we’ll go to Sister Bernadêtte’s class and hope that she banishes us to the back of the room again. At lunchtime, we’ll eat quickly. Afterward, we’ll play La Ronde with the only other girls in school we like: Marie Lourdes Jean, Caroline Saint Louis, and Elizabeth Lafrance. We’ll stomp our feet and sing our favorite La Ronde song which is also an old history lesson about Napoléon Bonaparte and Henri Christophe, “Commandant, Commandant du Cap!”

If there’s still time before our next class we’ll play Good Underwear. We’ll lower our voices so that the nuns don’t hear. One girl will step inside the circle and twirl around as fast as she can. We will inspect her underwear. If there are holes, we will laugh her out of the circle. If the elastic around the thighs is frayed, we will laugh her out of the circle. If the girl is bashful and refuses to spin around, we will pull her out of the circle and push someone else in. No one will have to push Yseult in. Playing Good Underwear is her second favorite thing in life. Yseult’s panties are the best. Her papa sends them from New York. My panties are not so bad today. When it’s my turn inside the circle, I’ll spin like a hurricane whipping though palm fronds. I’ll spin and spin while the other girls cheer: “Sak pa vire kilòt yo gen twou!” Spin, spin. Show us your good underwear.