Читать книгу RED & WHITE PHOENIX - KEITH POLLARD - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 1 HULL, HESSLE ROAD & THE FISHING INDUSTRY

ОглавлениеBefore I start my story, I would like to give you a brief background about the city of Kingston upon Hull, and particularly the famous Hessle Road area of the city where I grew up.

Hull was granted a Royal charter in 1229, and thus became known as Kingstown upon Hull – the river upon which it stands –and its’ history goes back as far as Anglo-Saxon times. What we now call Hessle Road was in the 19th century called Patrick Ground Lane, in the then Pottery District of Hull. Maps of the time show how the lane was in open countryside, with only a small concentration of buildings located around the still standing Vauxhall Tavern.

By then, it was becoming evident that Patrick Ground Lane, and the rough track from it that led to the village of Hessle, was quite unsuitable as an effective thoroughfare. By the early 19th century, many wealthy influential merchants had begun to move away from the town centre to new large mansions in the rapidly-developing villages to the west of the city, such as Hessle and its neighbour North Ferriby. The construction of a good road between the business centre of Hull and the merchants’ new mansions was essential.

Charles Frost, a Hull solicitor, was the main instigator of the building of the new turnpike road from Hull to Hessle. He received strong support from the majority of the local estate owners, with opposition coming from the competition-fearing trustees of the Hull-Anlaby-Kirk Ella turnpike, now Anlaby Road.

An Act was passed that enabled the turnpike to be built, and the first tolls were collected on July 28th 1825. For some twenty years, the road was identified on maps as Hessle New Road, being shortened to Hessle Road by the 1840s, and Patrick Ground Lane was no more. A toll bar was erected on the town and county boundary two miles to the west of the city centre, at Galley Clough Lane, roughly where Division Road stands today, and the road remained a turnpike or toll road until 1873.

During the 1870s, Hessle Road really began to expand westwards towards the neighbouring village of Dairycoates, which was also growing rapidly. 1872 and 1873 trade directories show that the Hull end of the road was becoming a busy commercial centre with grocers, butchers, fishmongers and more public houses competing for trade. The Vauxhall Tavern, the Alexandra Inn (formerly the Hessle Road Inn), four unnamed beer-houses and several coffee houses are also listed. However, in the area between Coltman Street and Dairycoates village, housing remained fairly sporadic and rural in nature. In Dairycoates, a Wesleyan Chapel had been erected, having been opened in December 1865, and the Dairycoates Inn was popular.

By the mid-1870s, building on the north side of Hessle Road had spread nearly a mile from Coltman Street up to Glasgow Street, whilst the south side was even more built-up. The commercial development of Dairycoates had continued with a post office, grocer, cobbler and butcher all flourishing – not to mention the Locomotive Hotel and the Temperance Hotel. The growth of the Hessle Road community saw several new churches being consecrated, including St Barnabas Church (1874), on the junction with South Boulevard, and a Congregational Church (1877) near Coltman Street. The growth in trade and improvements in transport were primarily responsible for this expansion, whilst the opening of West Dock (later Albert Dock) added to the boom and an influx of workers led to more and more housing development in the area.

The growth and importance of the railway system led to Dairycoates becoming a major railway junction, and when Hessle Road ceased to be a turnpike, the new freedom from tolls encouraged the introduction of the horse-drawn tram system across the city between 1875 and 1877. This service meant that it was now possible for people to commute even greater distances to work, further encouraging the growth of the suburbs.

Whaling was a big part of the history of Hull, with vessels sailing to the Scandinavian Peninsula in the latter part of the 1500s; and by 1618 vessels from Hull, along with those from Holland, were using the Norwegian island of Jan Mayen as a fishing station. Due to the English Civil War and the London-based Muscovy Company’s constant claims that the Hull whalers were ‘interlopers,’ the Dutch began to dominate whaling in the late 1600s, but, during the following century, government bounties and subsidies, along with the duty placed on imported oil and bone, helped the whaling business to grow in England.

In 1766, Samuel Standidge began the investment that laid the foundations of Hull as a major whaling port. War with England, and a blockade during the war with France, meant that the Dutch involvement in whaling was effectively dead by the beginning of the 1800s. By this time, the Hull fleet made up about 40% of the British whaling fleet, and peaked around 1820, when 62 vessels returned with the produce from 688 whales, worth approximately£250,000. This amount of trade in the city resulted in the expansion of other manufacturing.

1821, however, was a disaster for the whaling industry, with nine vessels crushed in ice. Many investors withdrew their money and the fleet was reduced by almost a third. In 1822, another six vessels were lost and eight others failed to catch a single whale. The industry declined to the extent that, by 1869, the Diana was the sole remaining vessel sailing from Hull. After this was wrecked off Donna Nook on the Lincolnshire coast, the whaling industry moved to Scotland. But by this time, the fishing industry had become of primary importance to Hull’s economy, and by the later part of the nineteenth century, it dominated the Hessle Road area of the city. Most of the families in this area lived in predominantly ‘two up, two down’ terrace houses in an area of about four square miles, bordered by Anlaby Road to the north, Coltman Street to the east, Goulton Street to the south and Hawthorn Avenue to the west.

We ‘Hessle Roaders’ liked to think of the area as a small village on its own, proud that we were from Hull and yet living in a close, friendly community, whose residents were honoured to say that they ‘come off Hessle Road.’ At its’ peak, the fishing industry sustained an estimated 50,000 local lives. There were more than 160 long-distance trawlers based in the port, several of them built locally in shipyards at Beverley and Selby.

The way that the owners of the ships named their vessels is very interesting. Hamblings’ trawlers all were all named after Saints, such as the St Romulus; all trawlers owned by Lord Line were ‘Lords’, such as the Lord Nelson; Kingston’s trawlers were named after jewels, like the Kingston Topaz; the names of Boyd Line ships began with ‘Arctic;’ and Ross Group trawlers’ names started with ‘Ross’.

Sadly, there were all-too-many dark days of tragedy over the years, deeply affecting the Hessle Road community, when Hull trawlermen were lost to the cruel seas. The words of skipper Philip Gay of the Ross Cleveland on March 5th 1968 leave a lasting memory. He called over the radio, “I am going over. We are laying over. Help us, Len, she’s going. Give my love and the crew’s love to the wives and families.” She was the third Hull trawler to be lost within 26 days. In modern times it was an unparalleled blow, even for a community well used to sacrificing its men folk who fished the unforgiving northern seas.

It fell to the workers of the Fishermen’s Bethel to tell families of their losses. It must have been an awful job breaking the bad news to relatives in days when large families were quite normal, and there were around 50 families for each ship. Firstly, they had to inform them that the company had lost contact with the ships and later, after no radio contact or sightings by other trawlers, they had to impart the tragic news.

The earliest losses were recorded in 1862, when three men died, and the last in 2000, when Michael Lambert, aged 59, died result of an accident on the Westella. In all, the list of Hull’s lost trawlermen has over six thousand names on it. The youngest were boys aged 14, lost or killed in accidents between 1862 and 1895, when children left school at an early age. One of my own uncles started work at 14, as clerk to an engineering company on St Andrews Dock. At the other end of the spectrum, James Coull, the cook on the Alonso, was the oldest trawlerman to die at sea, aged 71, when his ship was presumed to have hit a mine in 1944. Two Pollards are on the list, Joseph, who was killed in an accident on board the Achilles in 1863, and Thomas, who was lost overboard on the Tubal Cain in 1884, but I have been unable to find out if either were directly related to my family. I have traced my own family history back to 1690 on my father’s side, to a gentleman named Adenego in Bradford West Riding and to 1690 on my Grandmothers side Levi Gibbs from Fingest, a small village in Buckinghamshire. Funnily enough there was a Mesheck and Shadrach also on the Pollards side. But on my mother’s side, I have been able to go back only as far as 1841. Her mother, Louisa, was one of eight children whose maiden name was Boynton, from the South Shields area. But my grandfather on my mother’s side came from a seafaring family in Hull. My mother’s father was killed in an accident at sea, not on a trawler, but on a merchant ship. Apparently, he slipped, fell down the engine room steps, and died from his injuries. After that, my grandmother was unable to cope with five children, who were taken into the Sailors’ Childrens’ Society orphanage on Cottingham Road in Hull, where they stayed until they were able to be returned to their mother. My mother’s cousin, Ray Mearns, was aged 34 when he was a mate on the St Romanus, which went down with all hands on the January 11th 1968 on its way to fish off Norway. Not unusually at the time, the St Romanus had gone to sea without a radio operator. Many radio operators refused to sail on some ships because accommodation was so limited that they had to sleep in the tiny chart room. Trawlermen were very suspicious people, and some trawlers had ‘a bit of a shadow’ hanging over them – the St Romanus was one of these. There were stories about a crewman jumping overboard, saying he had decided to go home to see his girlfriend, and being drowned, along with a shipmate who had jumped over to try and save him. Another lad, who had previously sailed on her, had a premonition about going down with the ship and signed off before she sailed on her last trip. It was a feeling he could not explain, and he never went to sea again. Bill Weightman, my uncle’s brother-in-law, was skipper of the St Sebastian. At the age of 27, he was lost with all hands when the ship sank on the 29th September 1938, and left a wife and two children.

Several times, lads with whom I went to school or worked with, lost relations. When I was nine, the Lorrella and Roderigo went down on January 26th 1955. I can still hear the women crying as they ran through the streets, knocking at doors and calling out with the news of the sinkings – there were few televisions in those days and no local radio stations, so it was all word of mouth. Johnny Rose, the brother of my friend Colin, lived on Newton Street, only 100 yards from our terrace, was only 19 and was on the Roderigo. Tom Sutton, the father of my good friend Steve, who lived very nearby on Division Road, was on the Lorrella.

A Facebook group entitled ‘Hull’s Fishermens History’ contains a letter from the owners of the Lorrella, J Marr & Son, sent to the wife of one of the men who was lost, that shows the approach of the trawler owners towards their workforce, who were effectively casual labour – something that fishermen have fought for years to put right. I think the letter illustrates the stark reality of life for the men and their families who put the fish on our tables, and a look at this group’s Facebook page is well worth the time spent. The letter reads as follows:

Dear ‘Mrs Smith’

It is with very great regret that we have had to abandon all hope for the Lorrella or her crew. We wish to offer to you our deepest sympathy in your bereavement.

Nothing can be done to recompense you for your loss of your husband but we are very anxious that you should suffer no financial hardship until such time as your affairs are put in order and we are therefore making an ex gratia payment to you of £6. 11. 3d per week for the next eight weeks. Our cheque for the first week’s payment is enclosed.

Yours faithfully,

J. Marr and Son Limited

Another trawler to be lost was the Kingston Peridot, which went down with all hands when she capsized off Norway in 1968. One of the crew was Kenny Swain, who was on his first trip as a ‘decky learner.’ I had been to school with Kenny, and although he was two years older than me, I knew him quite well. He had been finished at the Langham Picture Theatre, where he worked as a projectionist, and so he decided to go to sea. I was chatting to him a couple of days before he joined the ship and wished him the best of luck on his new venture. That gives you a very sobering sense of mortality and even thinking about it now gives me shivers up my spine.

Accidents were numerous. My Uncle Jim got washed overboard and swears that he must have gone underneath the ship, as he saw the hull. Whilst the crew were looking over the side for him he was washed back on board behind those searching for him. All he sustained was a broken leg which was set and placed in a splint on board – so he completed the 19-day trip with a permanent limp.

Some fourteen poor souls never even got to sea or died when returning home in St Andrews Dock. One trawler, the Lady Jeannette, foundered off the dock, or ‘turned turtle,’ in the river, with the loss of nine lives. These unfortunate souls would probably have been in the accommodation area, getting their kit bags ready to go ashore at the time. The youngest was only 18.

What the trawlers used to do was to reverse into the lock to make it easier when they were leaving – it allowed them to merely sail straight out into the river and head for Spurn Point and north to the fishing grounds. Depending on which way the tide was running, they could come in four hours either side of high tide. The Lady Jeanette must have been coming in on the outgoing tide, as she had gone inland towards Hessle to turn round in the river, then used the tide to bring her back down towards St Andrews dock, whilst using the engines as a brake to ensure she did not come into the lock head too quickly. Apparently however, the tide was nearly at its lowest and she hit a sand bank, but with the river still running fast it pushed her over and off the bank in to deeper water. According to my father, who saw the tragedy, quite few men managed to swim ashore, but those inside the ship had no chance.

One of the most well-known, or infamous, disasters was that of the ‘super trawler’ the Gaul. Modern and supposedly watertight, the Gaul was only eighteen months old when she disappeared with the loss of her entire 36-man crew in the Barents Sea, 70 miles off Norway, during a fierce storm in February 1974. It was described as the ‘worst ever single trawler disaster.’ In the absence of any trace of the ship or its crew in the aftermath, it was alleged that the Gaul was engaged in ‘cold war’ espionage activities – claims repeated in a TV documentary the following year. After the examination of a wreck that was confirmed as the Gaul over 20 years later, a re-opened formal investigation concluded that an attempted emergency manoeuvre by the Gaul’s watch officer (a perfectly logical move to try to turn ‘into the sea’) caused 100 tonnes of floodwater to surge across to the starboard side of the ship, leading to a catastrophic loss of stability. Flooding took place through open doors, waste chutes and hatches and, losing her buoyancy, the Gaul sank very rapidly, stern first. The RFI report dismissed the idea that Gaul was involved in espionage or that she was in a collision, but relatives of the crew were still not satisfied and claimed that the ‘truth was still to be told.’

The list of trawlermen lost or killed just within a mile of where I lived was quite staggering:

Bean Street-36, Boulevard-28, Division Road-36, Edinburgh Street-16, Eton Street-46, Flinton Street-39, Harrow Street-39, Havelock Street-30, Liverpool Street-38, Regent Street-13, Rosamond Street-30, Rugby Street-32, Scarborough Street-37, Somerset Street-23, Strickland Street-37, Subway Street-24, Walcott Street-70 and Wassand Street-61. Those from the Boulevard were either skippers, mates, chief engineers or engineers. As they were the ‘upper class’ of the fishing industry they were the best paid, and this was a street with big grand houses, many of which survive today, even if many are somewhat run down. Most of the others who died were ‘rank and file’ crew hands. Not that the upper classes were in any way protected from tragedy. In all, 282 skippers alone failed to return home – 187 went down with their ships whilst the rest were either lost overboard or died whilst at sea. Everyone, whether the companies that owned the trawlers, the families of the crews, and the community as a whole, sustained significant losses – no-one who lived in the Hessle road area would have been unaffected by trawler tragedies. But more men did come home than did not, and for them there were both good times and bad. A particularly good ‘catch’ would result in the trawlermen receiving a very favourable amount of ‘settlings’ at the end of the trip, whilst on a less good trip it was not uncommon for them to ‘settle in debt’ after the deduction of allowances sent to wives and partners whilst they were at sea. It was well known that the trawlermens’ wives would frequently pawn their husband’s suits the minute they set sail. Then, a couple of days before the owner was due home, the suit would be taken back out, ready for use over the owner’s two days ‘recreation’ in the many ‘watering holes’ of the area. Such was the decline of the fishing industry that, by 1954, only three of these pawnbrokers remained – all of whom were making up their income with a second business. William Leighton added carpet dealing to his business plan and a Leighton’s carpet shop survived on Hessle Road until 2001. Issadore Turner, or “Izzy” as he was known to his clients, added gentlemens’ outfitting to his pawnbroking activities. It was a very hard life for the trawlermen and their families, but for the Hessle Road area of Hull the fishing industry was its lifeblood. When the industry was thriving, the area thrived too; and now that the fishing industry in Hull is no more, the character of the whole area has changed beyond recognition.

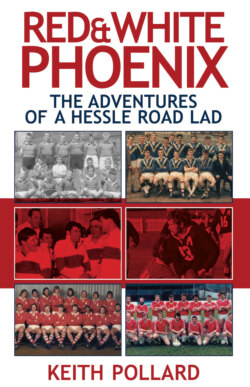

Clive Rutter’s Fish Merchant workers, my Dad on the leftClive Rutter’s workforce on St Andrews Dock