Читать книгу Insatiable Appetites - Kelly L. Watson - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1. Inventing Cannibals: Classical and Medieval Traditions

In a famous and gruesome tale from ancient Mediterranean mythology, the god Kronos (Saturn in the Roman incarnation) swallowed his children out of fear that he would lose his power at the hands of his son, as had been prophesied by his parents. Prior to eating his offspring, he had also castrated his father, Uranus, in a fit of jealous rage. After watching Kronos consume all but one of their children, Kronos’s sister-wife, Rhea, tricked him into eating a stone instead of their son Zeus. Later, as predicted, Zeus took revenge on his father and freed his brothers and sisters from Kronos’s body.1 Thus from acts of castration and cannibalism the leader of the Olympic Pantheon rose to power. Centuries later, in the 1820s, the Spanish artist Francisco Goya would memorialize this fateful event in the painting Saturn Devouring His Son. This story is only one of many mythological tales of cannibalism that have lasted the ages.

While humans consuming other humans has likely occurred since time immemorial, the Western idea that there are certain peoples who are prone to consuming other humans and that man-eating is directly related to other “savage” characteristics finds its origin in the ancient Mediterranean world. From these ancient traditions medieval genres like travelogues and bestiaries emerged. Thus by the time that Columbus arrived in the Caribbean, he carried nearly two thousand years of discursive cannibal history with him. Before jumping into an analysis of cannibalism in the late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century Caribbean, we must first understand the intellectual tradition inherited by early modern Europeans. Explorers, soldiers, settlers, and priests brought with them evolving traditions about how to interact and engage with difference. They inherited the belief that peoples who inhabit the far reaches of the world and people unlike themselves were often man-eaters. This chapter traces ideas about cannibalism from Ancient Greece to medieval western Europe through a survey of some of the most influential texts.

The Origins of Anthropophagy in the Ancient Mediterranean

In Herodotus’s Histories, he describes several types of man-eating practiced by both Greek and non-Greek peoples, including acts of vengeance cannibalism, starvation cannibalism, and ritualized man-eating. The first of these tales of cannibalism, in book I, is an act of vengeance by a group of Scythian hunters angered by the harsh treatment they received at the hands of Cyaxares, the king of Media, when they returned empty-handed from a hunt. Herodotus writes, “They [the Scythians] felt that this treatment from Cyaxares was unwarranted, and they decided after consideration to chop up one of their young pupils, prepare him for the table in the way they had usually prepared wild animals, and serve him up to Cyaxares.”2

The second story of cannibalism in The Histories also involves vengeance. Astyages, the son of Cyaxeres, had a dream that his daughter Mandane would bring great danger to his kingdom. So, in order to preserve his power, Astyages married her to an inferior nobleman, a Persian named Cambyses. Soon Mandane became pregnant, and Astyages had another dream, which foretold that her offspring would rule in his place. Once the child was born, Astyages called upon a trusted relative named Harpagus and asked him to kill his grandson. Harpagus had no choice but to agree, but he was unable to complete the task himself, so he passed it on to a herdsman named Mitradates. Rather than kill the boy, Mitradates and his wife, who had just given birth to a stillborn child, passed him off as their own and put their deceased child in his place as evidence of the deed. Years later Astyages discovered that his grandson, called Cyrus, was still alive and brought Harpagus before him to answer for his crime. After pretending to be happy with this turn of events, Astyages told Harpagus to invite his own son to greet Cyrus. “However, when Harpagus’ son arrived, Astyages murdered him and dismembered him. He baked some of his flesh, stewed the rest and prepared it all for the table.” After Harpagus had eaten, Astyages asked him if he enjoyed the feast and called the servants to bring in a platter containing the boy’s head, hands, and feet. Rather than recoil in terror or grief, Harpagus told the king that he could do no wrong and returned home with his son’s remains. Years later, at the urging of Harpagus, Cyrus rebelled against his grandfather and ruled in his place, thus fulfilling Astyages’ dream premonition. In another story of cannibalism in the sordid, sad tale of the kingdom of Media, troops under Cyrus’s father, Cambyses, resorted to cannibalism in the face of starvation on an ill-fated attempt to conquer Ethiopia. Cambyses had been warned that this mission was foolhardy, but it took the desperate cannibalistic acts of his soldiers to finally convince him of this.3

While the Scythians are implicated in the revenge cannibalism of book I of The Histories, it is in book IV that they receive greater scrutiny and become the paradigmatic cannibals. Herodotus begins by describing the conquests of the Scythians and Darius’s plan to seek vengeance on them for their acts of aggression against the Medes. He then relates several different versions of the origins of the Scythian people, one of which traces their descent to the offspring of Heracles and Echidna, a snake-human hybrid. Much of book IV is taken up with a detailed description of the people and places in the region of Scythia. But despite the anthropophagous reputation of the Scythians, it is in fact their neighbors that Herodotus accuses of institutionalized cannibalism: “North of this agricultural region there is a vast uninhabited area, and then there are the Cannibals, who have their own distinct way of life and are not Scythian at all.”4

There are other people Herodotus accuses of occasionally committing acts of cannibalism, but the Cannibals are the only group to be defined by these acts. For example, he describes the funerary practices of the Issedones, who prepare a special feast on the occasion of a father’s death made of sacrificial animals and the dead man’s body.5 Herodotus is actually quite careful to distinguish among types of man-eating. He passes only minimal judgment on ritualized cannibalism, like that practiced by the Issedones. Acts of revenge cannibalism similarly are not judged as significantly worse than other acts of revenge, all of which bear severe consequences for those involved and their descendants. In other words, in tales of revenge cannibalism, it is not that a human being is killed and consumed that causes repercussions; more often it is the rashness and pride of the perpetrators that come back to haunt them. Thus Herodotus distinguishes between cannibalism (ritual, starvation, revenge) and Cannibals (people who actively seek to consume human flesh).

Throughout the Histories, Herodotus makes sure to give his reader all available information on a topic even if he does not find his sources very credible. For example, of the different versions of the origins of the Scythians that he relates, he indicates which he finds most reasonable. He is unconvinced by the version preferred by the Scythians themselves, which ties their origins to Heracles and Echidna. That does not mean, however, that Herodotus’s conclusions are always plausible. In his lengthy narrative on the regions surrounding Scythia, he describes a group of people living on the edges of the kingdom: “Far past this rugged region, in the foothills of the mountain range, live people who are said—men and women alike—to be bald from birth; they are also supposed to have snub noses and large chins, to have a distinct language, to dress like Scythians and to live off trees.” Beyond the lands of the bald people, Herodotus reports, he has only the sparest of evidence. He claims that the bald people tell of “goat-footed men living in the mountains, and that on the other side of the mountains there are other people who spend six months of the year asleep,” but he does not trust these reports. In fact in book III he offers a statement similar to that of Montaigne more than a thousand years later: “If one were to order all mankind to choose the best set of rules in the world, each group would, after due consideration, choose its own customs; each group regards its own as being by far the best.”6 Thus much more than most writers who followed him, Herodotus treats the act of cannibalism carefully and with a crude nod to cultural relativism.

Much has been written about the plausibility or implausibility of the existence of Herodotus’s Cannibals, but whether or not he is to be trusted on the topic, other classical writers followed his example and believed that Scythia and other regions on the edges of the “civilized world” were populated by man-eaters.7 Strabo describes the cannibalistic practices of the Celtic inhabitants of the British Isles, who are “more savage” than others in the region, practice incest, and are “man-eaters as well as heavy-eaters.” To shore up this claim, which he admits comes from less than trustworthy sources, he looks to the reputation of the Scythians for support: “And yet, as for the matter of man-eating, that is said to be a custom of the Scythians also and in cases of necessity forced by sieges, the Celti, the Iberians and several other peoples are said to have practiced it.” Thus, it is because the anthropophagy of the Scythians is so notorious that he finds the tales of Irish cannibalism to be somewhat credible. Furthermore, like Herodotus, Strabo maintains that there is a difference between resorting to cannibalism out of necessity and being a Cannibal, although he does seem to criticize acts of starvation cannibalism, as he asserts that only those on the fringes of “civilization” have resorted to it.8

Pliny the Elder echoes these sentiments in book VII of his Natural History. In the opening pages of this section, he discusses the authoritativeness of his work, pointing to men like Herodotus as his trustworthy sources: “We have pointed out that some of the Scythian tribes and in fact a good many, feed on human bodies—a statement that perhaps may seem incredible if we do not reflect that races of this portentous character have existed in the central region of the world, named Cyclopes and Laestrygones, and that quite recently the tribes of the parts beyond the Alps habitually practised human sacrifice, which is not far removed from eating human flesh.”9 Furthermore, Pliny argues, even if some of the things he describes may seem fantastic or dubious, given that humans tend to regard the unfamiliar with suspicion, they are all supported by the best sources that he could find. He presents himself as a skeptic who is naturally inclined to view evidence with measured suspicion. When describing parts of Africa for which his information is dubious, he refers to them as “imaginary.”10 And when he describes a litany of monstrous humans, he presents such specimens as real to the best of his knowledge, including people born with horse hooves; humans with ears large enough to cover their whole body; a race known as the Blemmyes who have no heads, only a mouth and eyes on their chest; and people with strap-like feet who must crawl instead of walk.11 In this way he assures readers that even if one or more of the claims he makes turn out to be false, the rest of the work should not be discredited as he was merely working from the knowledge of others.

In addition to physically monstrous humans, Pliny discusses humans whose cultural practices and traditions are the cause of their monstrosity. For example, the Gamphasantes “do not practice marriage but live with their women promiscuously” and “go naked, do not engage in battle, and hold no intercourse with any foreigner,” while the people of the Atlas tribe do not dream like other humans nor assign proper names to individuals, which have caused them to fall “below the level of human civilization.” The aptly named Cave-dwellers live in caves, eat snakes, and are unable to speak.12 Monstrous humans, then, are those whose bodies are well outside the normal range for humanity or whose cultures fail to meet the minimum standard for rationality and civilization as Pliny defines them.

In his descriptions of the various kinds of humans that exist in the world, Pliny specifies three places where monstrous humans are most likely to live: sub-Saharan Africa, the central Asian steppes, and Southeast Asia. In other words, monstrous humans reside in the places farthest from the influence of Mediterranean civilization. Out of all of these regions, it is the area around Scythia in the central Asian steppes that receives the most attention. Pliny lists the various tribes that fall under the general umbrella term Scythian. Some of these tribes he designates as civilized and others as savage. Those groups that inhabit the edges of the Scythian world are the recipients of most of Pliny’s condemnation. Some of the lands just beyond the “Scythian promontory” are too snowy to be inhabited, while others are “uncultivated because of the savagery of the tribes that inhabit it. This is the country of the Cannibal Scythians who eat human bodies; consequently the adjacent districts are waste deserts thronging with wild beasts lying in wait for human beings as savage as themselves.”13 The lands inhabited by the Cannibal Scythians appear to mirror the savagery of its supposed inhabitants. Savage people inhabit savage lands.

Book VII of Natural History is devoted to describing humanity’s various forms and capacities. A number of monstrous groups live in the lands just beyond the Scythians, including “people dwelling in forests who have their feet turned backward behind their legs”; people who “drink out of human skulls and use the scalps with the hair on as napkins hung round their necks”; and Albanians, who “are born with keen grey eyes and are bald from childhood.”14 These descriptions underscore an important element of the intellectual tradition that early modern Europeans would inherit: the conflation of physical and cultural “deformities” into a single category described variously as savage, barbarous, or monstrous. In this way an individual who looks like a “normal” human but turns out to be a cannibal is as far from “civilized” as physically divergent creatures like Cynocephali or Cyclopes.

Pliny spends the rest of book VII discussing human physiology, devoting considerable space to sex and reproduction. He links the earlier section on monstrosity with the section on physiology through the example of the “Hermaphrodites formerly called androgynes” and individuals who had transformed from female to male or vice versa. Thus individuals (and in some cases whole tribes) who are born with ambiguous genitalia provide the necessary link between variations of the human form and the “science” of sex and reproduction. Pliny reports that humans are the only species who indulge in procreative copulation all year round rather than during a fixed season. Human gestation, in his estimation, ranges from six to ten months. Pregnant women first feel the movement of the fetus on the fortieth day if it is male and on the ninetieth day if it is female. The birth of male children was reportedly easier for the mother. Together these beliefs about reproduction reinforce the notion of maleness as humanity’s default (and more “natural”) state.15

Like other classical writers, Pliny found the female sex both degraded and frighteningly powerful. Women’s bodies were believed to do mysterious things that could have a profound impact on the environment. Contact with menstrual blood, for example, “turns new wine sour, crops touched by it become barren, grafts die, seeds in gardens are dried up, the fruit of trees falls off, the bright surface of mirrors [in] which it is merely reflected is dimmed, the edge of steel and the gleam of ivory are dulled, hives of bees die, even bronze and iron are at once seized by rust, and a horrible smell fills the air; to taste it drives dogs mad and infects their bites with an incurable poison.” Thus women were in some way always monstrous. Even in death, the corpses of men float on their back, while women float on their face “as if nature spared their modesty after death,” preserving the idea that women and men are fundamentally different in both form and capacity.16 Such sentiments were echoed often by early modern Europeans in their encounters with Indigenous Americans.

Early Christianity

At roughly the same time that Pliny was composing the Natural History, the religious teachings of Jesus and his disciples began spreading around the Mediterranean. The early years of Christianity were difficult for its adherents; they faced suppression and vilification for their beliefs, including accusations of anthropophagy. As evidenced by writers like Herodotus, Strabo, and Pliny, such claims about those who resided outside of civilization were not uncommon. The allegations against the Christians, however, remind us that one did not need to be geographically removed from the polis to be considered uncivilized or Other. Individuals whose cultural or religious practices differed from the masses, whose traditions remained mysterious, or who posed a threat to society as a whole could easily find themselves suspected of anthropophagy. Traditionally scholars have understood the accusations against the early Christians as a misinterpretation of the ritual of the Eucharist by the pagan majority. While this symbolic correlation seems obvious (and in fact will be deployed by English settlers against their French neighbors in America nearly a millennium and a half later), the Anglican theologian Andrew McGowan argues that this simplistic explanation fails to account for the fact that other groups were accused of cannibalism who possessed no such ritual.17

In the first century ce, Christians were accused of both cannibalism and incest. Much of the discussion about Christian practices among the pagan Romans centered on what transpired at their ritual meals. Pliny the Elder’s nephew, referred to as Pliny the Younger, wrote a letter to Emperor Trajan while serving as the governor of Bithynia-Pontus (in modern-day Turkey) regarding his interactions with Christians. In addition to providing a useful window into the prevailing Roman policy toward Christians at the time, Pliny the Younger’s letter also hints at the mystery surrounding Christian meals. In his account of his initial investigations into the crimes of Christians, he argues that their “pertinacity and inflexible obstinacy” alone “should certainly be punished,” and he also hints at other questionable practices. He reports on the confessions of several Christians who described their religious practices: after pledging themselves to Christ, “it was their custom to depart and meet again to take food; but it was ordinary and harmless food, and they had ceased this practice after my edict in which, in accordance with your orders, I had forbidden secret societies.”18 According to Pliny the Younger, the accused Christians steadfastly maintained that their ritual meals were harmless. The need to defend their ritual meals reinforces the fact that speculation ran rampant in the Roman world.

Other sources from the first few centuries of the Common Era also mention the slanderous accusation of cannibalism against Christians. The second-century Christian apologist Athenagoras writes, “Three things were alleged against us: atheism, Thyestean feasts, Oedipodean intercourse,” and asserts that if any evidence of such crimes could be found among the Christian population, then they deserved to be punished.19 The charge of Thyestean feasts refers to the legendary conflict between Thyestes and his brother Atreus over the Mycenaean throne. Thyestes’ children were served to him as an act of vengeance over his seduction of Atreus’s wife, Aerope. Later Thyestes raped his own daughter, thus committing a reversal of Oedipal incest.20 Athenagoras dismisses the charges against Christians as absurd but nonetheless devotes a great deal of time to refuting them. He argues that the charges of incest and sexual impropriety are illogical given that Christians focus their corporeal lives on preparation for the eternal spiritual one and as such are not “enslaved to flesh and blood, or overmastered by carnal desire,” following the Pauline belief in the spiritual superiority of celibacy. He argues that the Romans are accusing the Christians of the very things that they themselves are guilty of: sodomy, prostitution, and more. In a curious passage Athenagoras accuses non-Christian Romans of being pederasts, adulterers, and sodomites, indicating that he believes such acts of promiscuity are innately cannibalistic as they do violence to the body: “These adulterers and pæderasts defame the eunuchs and the once-married (while they themselves live like fishes; for these gulp down whatever falls in their way, and the stronger chases the weaker: and, in fact, this is to feed upon human flesh, to do violence in contravention of the very laws which you and your ancestors, with due care for all that is fair and right have enacted).”21 Christians were accused not only of sexual impropriety and man-eating but also of incestuous orgies and the consumption of babies. Their supposed crimes went well beyond the violation of social norms; they were believed to be in violation of natural law itself.

The accusations of incest and anthropophagy were widely reported by men like Theophilus of Antioch, Justin Martyr, Origen, Lucian, Clement of Alexandria, Tertullian, and in great detail by Minucius Felix.22 These were not mere rumors, as they had real and tragic consequences for Christians in the Roman Empire, as is evidenced by the case of the Christians of Lyon and Vienne in 177. After a particularly tumultuous year, in which the Christian population came under increasing suspicion, Christians were forced to stand before the governor to face charges of incest and cannibalism. For these crimes the defendants were executed and became martyrs. An imperial edict stated that Roman citizens should be decapitated, not tortured, but although one of the defendants was a Roman citizen, he was tortured before being thrown to the beasts with his fellow believers in Christ.23 The denial of the appropriate sentence in this case indicates that perhaps accusations of such a horrific crime as cannibalism rendered the privileges of Roman citizenship null and void.

Ultimately fear of unknown religious practices led to rumor and conjecture, resulting in the accusation of cannibalism, for why would a group want to keep their meal practices secret if not for some nefarious purpose? Toward the end of his letter to Trajan, Pliny the Younger refers to the growth of Christianity as a contagion that is spreading quickly.24 The danger inherent in not knowing becomes even more frightening if the mystery appears to be growing. As Christian adherents spread throughout the Roman world, their hidden and mysterious rites took on a new and terrifying face. Centuries later, men like Columbus and Vespucci would write of their fears of the contagious nature of practices like cannibalism and sodomy.

Classical Cannibal Discourse

Taken together all of these accusations of cannibalism in the classical world help us to better understand a number of important precedents that would profoundly shape the minds of early modern explorers, conquerors, evangelists, and settlers as well as those back in Europe reading of the American experience. While ancient Western writers accused a variety of peoples of cannibalism, the Scythians stand out as the most notorious group.25 Their alleged anthropophagy was prevalent in the literature, as was their supposed uncouthness and stupidity. Herodotus was careful to distinguish between the Scythians and the Androphagi, for example, underscoring the fact that although some Scythian practices might be savage and cannibalistic, they were not solely defined by their supposed anthropophagus ways. In spite of Herodotus’s contradictory and complicated depiction of Scythian peoples, it is the negative aspects of their culture that proliferated in popular discourse.26 The first-century Jewish chronicler Josephus, for example, described the Scythians as “reveling in the murder of humans, and only slightly better than wild beasts.”27

The proliferation of the myth of Scythian cannibals across time and space demonstrates the staying power of such accusations. But even more important, these accusations of anthropophagy against the groups collectively called the Scythians not only created the trope of cannibalism in the Central Asian steppes but helped to establish precedents regarding who cannibals were, what they were like, and where they lived. These accusations also constrained ways of thinking about cannibalism in the ancient Mediterranean world, for if Scythians were cannibals, then one knew what a cannibal was: a Scythian. This kind of circular logic will be repeated throughout the Middle Ages and the early modern period. Those who were believed to be cannibals because of their geographic location (or other defining characteristics, such as cultural practices or appearance) become themselves the very definition of “cannibals.” Thus the definition of cannibal is more complicated than merely one human who consumes another, encompassing a web of assumptions about Otherness as well.

The endurance of the Scythian reputation for cannibalism also reveals how whole groups of people were conflated into artificial categories and how the differences between them were minimized. The category of Scythian encompassed a rather poorly defined group of people inhabiting a region whose boundary was equally vague. Discursively, however, these differences and vagaries mattered little. The Scythians were cannibals, whoever they were and wherever they lived. Again this pattern will be repeated often in the following millennia.

The anthropophagus accusations lodged at other groups, like Celts and Christians and even starving soldiers, reveal another important discursive legacy of the ancient world. If one were reading Herodotus, Pliny, or Strabo in a Mediterranean metropole like Athens or Rome, it might seem that the vast majority of cannibals live on the edges of civilization, places whose landscapes mirrored the savagery of their people. In other words, the overall impression from these works is that the cannibal always lives elsewhere. Yet these authors also described acts of human consumption that supposedly occurred a lot closer to home. In each of these examples, however, the act of cannibalism was an act of desperation or revenge, not a defining cultural practice. While the unfortunate Harpagus might have unknowingly consumed his own son, this act is presented as an isolated incident that arose from the intertwining of prophecy, vengeance, and overzealous passion. In this case cannibalism occurred under extreme circumstances rather than as a habitual act. The driving force of bloodlust is undeniable in such tales, but the object of rage and hatred is pointed in a specific direction rather than indiscriminately at all human beings; the paradigmatic cannibal society was presumably one in which the bonds of shared humanity were weak and all human beings were potential food sources. Even when Cambyses’ troops were driven to cannibalism in the desert, it was out of desperation, not desire.

In the case of the Christians in the Roman Empire, however, a complicated situation developed in which a group a people who inhabited “civilization” were accused of ritualized, institutionalized cannibalism. The Christians were not an undifferentiated Other living somewhere on the fringes of civilization; they were not people who had been raised as savages, yet they chose to abandon their traditions and follow a path leading to inhumanity. Living among civilized people did not automatically make them part of civilization. In contrast to Pliny’s lurid descriptions of cannibalistic monsters in the far reaches of the world, the Christians who were accused of cannibalism in the second century seemed to have chosen rather than inherited the practice of anthropophagy. This presents a challenge to the simplistic assertion that cannibals are always fundamentally Other. If there are people living in Rome or Antioch who are secretly cannibals, then the threat of savagery and consumption is much closer at hand. One need not travel to distant lands to be exposed to threats to one’s body and spirit. These accusations highlight the distinction between the internal and external Other. Not only is this important in furthering our understanding of the concept of the Other, but it will be important in tracing the discourse of cannibalism through medieval Europe and the early modern Americas, for the strategies necessary to combat the threat of savage man-eaters need to change if the cannibals are literally among us.

Underscoring many of the descriptions of man-eaters in the classical world was the symbolic linkage of people who consumed other human beings with monsters and the monstrous. In the case of Pliny the Elder, the two were often conflated; he describes cannibals as both humans and monsters in the Natural History. Some of his richest descriptions of monsters appear in the chapter devoted to man, whom he considers the highest of all animals. Given this, it seems clear that for Pliny, the human race came in many forms with a large number of variations. Alongside Scythian cannibals he includes a description of Cyclopes, people whose feet are turned backward, Androgyni, individuals whose saliva can cure snakebites, and others who possess body parts with a variety of magical abilities.28 What, then, are the parameters for defining humanity? It is not size, skin color or texture, sexual dimorphism, number of extremities, possession of certain sensory organs, nor sociality, language, or culture. Rather the reader is left with a confused understanding of humanity. What is clear, however, is that not all humans were equal in Pliny’s mind.

The line between human and inhuman, or perhaps more precisely human and monster, was (and continues to be) a site of negotiation. Can one become a monster? When does a human become a monster? Is it achieved through acts or physical appearance? For modern-day readers, the designation monster when used in reference to human beings tends to be awarded based on actions. For example, one might come across the following sentence: “Adolf Hitler was a monster.” This usage of the term feels familiar as it is not referring to Hitler as physically monstrous but rather that his horrific actions were the root of his monstrousness. At least in polite conversation, we tend not to use monster as a descriptor for people whose bodies deviate from the norm. Furthermore modern readers tend not to believe that the Cyclopes, mermaids, or Blemmyes are or ever were real. Since the Enlightenment there has been a clear shift away from the belief that humanity is widely diverse in form and an increased skepticism about the existence of seemingly monstrous or magical beings. But for much of the first two millennia of the Common Era, belief in such creatures was widespread. Yet while the other monstrous creatures described by Pliny have been rejected as mere fantasy, the man-eater who dwells on the fringes of civilization has not been rejected so readily. The figure of the cannibal is a central site through which the very definition of human is negotiated. As we move forward in time, it is important to take note of whether or not cannibals were perceived as monstrous humans or humanoid monsters.

Finally, before moving on to a discussion of the discourse of the cannibal in the European Middle Ages, we must pause one more time to interrogate the place of gender, sex, and sexuality. For most classical writers, the default form of humanity was male, and thus any reference to so-called Cannibals primarily signified men. The connection between reported acts of cannibalism and sexual deviance is also important. Taboo sex and cannibalism both represented the corruption of the body; each was seen an embodied act whose existence challenged the hegemonic power of the given society. Thus, regardless of what government or religion held sway, the control of bodies and bodily acts was reserved for the state. It was common in ancient Greece for enemies to be denied proper burial, as is detailed in Sophocles’ play Antigone. The rituals associated with death often center on control of the body. For early Christians the issue of body disposal was fraught with tension as debates over the nature of resurrection, whether it would be bodily or spiritual, raged. The denial of a proper burial or bodily disposal might mean that an individual would never achieve eternal life. In a similar fashion, for early Christians, even while one was still alive defilement of the body risked one’s eternal salvation.

Within the early Christian Church itself there were accusations that certain hidden and mysterious sects did actually perform the kinds of rights that the Romans accused them of. In the fourth century Bishop Epiphanius of Salamis believed that a Gnostic Christian sect known as the Phibionites or Borborites took part in all kinds of illicit and damning acts, including cannibalism:

They [the Phibionites] set the table with lavish provisions for eating meat and drinking wine. But then, after a drinking bout and practically filling the boy’s veins, they next go crazy for each other. And the husband will withdraw from his wife and tell her—speaking to his own wife!—“Get up, perform the Agape with the brother.” . . . For besides, to extend their blasphemy to heaven after making love in a state of fornication, the woman and man receive the male emission on their own hands. And they stand with their eyes raised heavenward but the filth on their hands, and pray, if you please—the one called Stratiotics and Gnostics—and offer that stuff on their hands to the actual Father of all, and say, “We offer thee this gift, the body of Christ.” And then they eat it and partake of their own dirt, and they say, “This is the body of Christ; and this is the Pascha, because of which our bodies suffer and are made to acknowledge the passion of Christ.”29

This lurid description highlights the way acts of cannibalism and sexuality were linked. Not only were they believed to have happened during a single ritual, but their pairing suggests that sexual impropriety set one on a path toward rejection of all that “civilization” held dear. In the vast majority of classical tales of cannibalism, it is the body of an infant or a young man who is consumed, linking the act of human consumption with homosexual acts. In the previous example, semen is both an offering for God and the body of Christ itself. If we understand that accusations of cannibalism in some way represent the fear of the most horrific elements of human nature, and the fear that such horrors existed hidden in plain sight even in the “civilized world,” then the connection between cannibalism and sexuality (in particular nonprocreative sex) takes on greater importance. The fear of cannibalism carries with it the fear of female desire and “inappropriate” male desire. When the norms of gender and sexuality are subverted, when women commit adultery or become promiscuous or when men copulate with other men, the social body itself is threatened. The presence of unbridled indulgence of the flesh (whether through sex or consumption) indicated a society and a social order that was out of control.

Medieval Western Europe

As Christianity spread and the early Church was still developing its canon, a large number of texts about Jesus and his disciples were written, most of which have since been deemed apocryphal. Among these was the Acts of Andrew, written around the middle of the third century. The most common version of the Acts traces the proselytizing efforts and miracles of Saint Andrew after the death and resurrection of Jesus. In addition to the more well-known and accepted version, another account of Andrew’s exploits was written in Greek at the end of the fourth century. This version, called the Acts of Andrew and Matthias, the Acts of Matthew and Andrew in the City of Cannibals, or the Acts of Andrew and Matthias among the Anthropophagi, is a much more fanciful rendition of the tale. The edition that remains is an Old English translation of a no longer extant Latin translation of the original Greek.30 The traditional Acts of Andrew mentions nothing about cannibalism, which is a prominent feature of the more dubious Acts of Andrew and Matthias.

The Acts of Andrew and Matthias begins with Saint Matthew’s journey to spread the gospel of Jesus in the city of Marmadonia (Mermodonia in some versions), which was supposed to be in Scythia. The Marmadonians are described in less than flattering terms: “The men who were in this city ate no bread and drank no water, but ate men’s flesh and drank their blood. And whatever foreign man who came into the city, it says that they immediately seized him and put out his eyes, and they gave him a potion to drink that was blended with much witchcraft, and when he drank this drink, immediately his heart was undone and his mind overturned.” Unsurprisingly Matthew is captured and imprisoned upon his arrival in the city. While in prison, he prays to God for his deliverance. God answers, telling him that after twenty-seven days Andrew will come to his rescue. The Lord convinces Andrew to go to Marmadonia and rescue Matthew. Andrew then boards a ship, which turns out to be helmed by God himself in disguise, who warns him of the great torments that he will suffer on this mission. However, God also assures Andrew that it will be worth it as there are many among the cannibals who will make great converts. When he arrives in Marmadonia, Andrew swiftly rescues Matthew from prison and begins to spread the word of God throughout the city. Soon afterward the jailors “came so that they could lead the men out and make them into food, and they found the doors of the prison open and the seven guards lying dead,” causing them great consternation. A fight between the Devil, on the side of the Marmadonians, and Andrew ensues, during which Andrew is imprisoned and tortured. While captive Andrew sends forth a flood through the city from his mouth, drowning the children and animals, while God surrounds the city with fire so that no one can escape. After this the cannibal Marmadonians repent and become devout followers of Christ.31

This rather absurd tale provides a nice bridge between the accusations of cannibalism lodged at Christians in the late Roman Empire and the discourses of cannibalism in medieval Europe. The story makes Christians’ denial of their man-eating rituals explicit as it presents them as warriors against the scourge of cannibalism. While this reversal turns one aspect of prevalent cannibal discourses on its head, it preserves much of the spirit of cannibalism as an Othering device. It also reinforces the idea that cannibalism is common on the fringes of civilization, especially in Scythia. By the fourth century, when Christians dominate in Rome, they are presented as heroes over pagan cannibals. No longer were the Christians the enemy within.

From the fall of the Roman Empire to Columbus’s landing in the Caribbean, tales of cannibalism were prevalent throughout western Europe. Such tales took a number of different forms, from travel literature to romances, church histories, and folk tales. The tendency for stories of cannibalism to locate man-eaters on the fringes of civilization continued, and so the Scythians remained a common recipient of these accusations. Instead of pointing fingers at Christians in the late Roman Empire, the accusations shifted toward other groups whose beliefs, rituals, and practices seemed mysterious, savage, or heretical. Common among these accused man-eaters were Jews, Muslims, pagans, witches, Africans, and Asians. As with the classical examples above, I will proceed chronologically, focusing on a number of key texts that appear to have had the greatest impact on Europeans in the Americas.32

Following the example set by Pliny in the Natural History (among others), the seventh-century Spanish bishop Isidore of Seville compiled an encyclopedia, called Etymologiae, which had a profound impact on medieval culture and knowledge. Over the next millennium, Isidore’s work was published and republished so often that nearly a thousand copies survive to this day, a staggering number in comparison to other extant medieval manuscripts. Isidore drew heavily from classical writers, including Pliny the Elder, Tertullian, and Martial; much of the Etymologiae is merely a rehashing, and often a direct borrowing, of earlier sources. It should come as no surprise that cannibalism is among the vast number of topics that Isidore discusses. In his exhaustive list of the peoples of the world, he describes the Scythians and their various neighbors and subdivisions. He indicates that the Scythians are descended from Magog, the second son of Japheth (the supposed forebear of all Europeans), who was the son of Moses. Isidore describes the Thracians as the most ferocious of all peoples living around Scythia. Echoing Pliny the Elder, he writes, “Indeed, they were the most savage of all nations, and many legends are recorded about them: that they would sacrifice captives to their gods, and would drink human blood from skulls.” He says that the Albanians are born with white hair (“because of the incessant snow”), differing slightly from Pliny, who argued that they were bald from childhood. Despite these descriptions of the Scythians and their neighbors, Isidore specifically locates the homeland of the Cannibals as somewhere beyond India. “The Anthropophagians . . . feed on human flesh and are therefore named ‘man-eaters.’”33

He also describes many different kinds of monstrous humans, the Plinian races, as they have come to be called, but adds a new dimension to the subject. Since Isidore is writing from a Christian perspective, unlike many of the sources he draws from, he cannot discuss monsters without clarifying their place in God’s creation. As he tells us, there are no beings that are contrary to nature, and nothing can be contrary to God’s will. He is concerned with developing a more rational approach to understanding monsters and human monstrosities and is careful to distinguish between beings that are portents and those that are unnatural. Nonetheless he reports on the existence of Cynocephali, Cyclopes, Blemmyes, Sciopodes, Giants, Pygmies, the Hippopodes, and the Panotians (people with ears so large that they cover their whole body). While not all of these monstrous beings lived in Scythia, several did, and Isidore reports that among the tribes that reside in this region “some cultivate the land, whereas others are monstrous and savage and live on human flesh and blood.”34 Thus the Etymologies maintain the earlier traditions of representing cannibals as both actual monsters, residing near monsters, or being like monsters. Anthropophagi do not appear to fit neatly into any category, but it seems that Isidore views man-eaters as human—perhaps monstrous but human nevertheless.

Isidore presents a common premodern understanding of human temperament as directly related to the climate and geography of the region that a group inhabits: “People’s faces and coloring, the size of their bodies, and their various temperaments correspond to the various climates. Hence we find Romans are serious, the Greeks easy-going, the Africans changeable, and the Gauls fierce in nature and rather sharp in wit, because the character of their climate makes them so.”35 This climatic theory of human development will be echoed repeatedly by European travelers to the Americas well into the modern era.

A few centuries after Isidore of Seville composed his encyclopedic work, European Christians embarked on series of conquests of the Holy Land. The accounts of the First Crusade, which lasted from 1096 until 1099, add another important, and perplexing, layer to the medieval discourse on cannibalism. While one might expect that the Catholic Crusaders would follow earlier precedents and accuse their Muslim enemies of cannibalism, this is not the case. Rather the firsthand reports describe Catholic soldiers consuming Muslims. In 1098, during the Siege of Ma’arra, in modern-day Syria, there were a surprising number of reports that the Crusaders ate the bodies of their enemies. While the reports agree that bodies were consumed, the how, why, and who are not quite as clear. Some chroniclers blame the acts on a perhaps fictitious group of impoverished soldiers known as the Tarfur, reinforcing that even if acts of cannibalism did happen, they were committed by an outsider group. Equally important, however, is the fact that these reports stressed that the only bodies the Crusaders consumed belonged to Muslims; even when driven to desperate acts, the soldiers maintained a distinction between the bodies of their compatriots and those of their enemies. Symbolically, of course, treating the bodies of one’s enemies as food dehumanizes them. But it also, in some ways, dehumanizes the consumer. As the historian Jay Rubenstein notes, however, “behind each narrative direction lies a common impulse: the recognition of cannibalism not as an aberration from the ethos of holy war but as an aspect of it.”36 In a holy war, which is by its nature understood as justified, the means must always support the ends. This same logic will be repeated by English settlers in North America who resorted to cannibalism to survive in a world that they believed was hell-bent against them.

Medieval Travel Narratives

Typically in the Middle Ages cannibals were portrayed as either distant foreigners from the East, witches, Jews, or savage forest-dwelling wild men. The cannibal was always an individual who resided outside of mainstream Christian culture. European traditions about the Other reinforced a civilizing agenda, in which strangers were meant to be converted to the proper Christian way of life or eliminated. Because these processes were set in motion long before the first European set foot in the “new world,” the writings of early explorers tended to focus on the differences between themselves and the inhabitants of the Americas. As it was common in medieval Europe for individuals to label peoples and cultures that were quite different from their own as cannibalistic, this led to an abundance of references to cannibalism in the Americas. Additionally medieval European writings were rife with references to the threatening powers of women, as evidenced by the numerous accounts of witches, for example. The medieval tendency to portray women’s sexual freedom as threatening was continued in the Americas.37

Writings about travel to exotic lands were enormously popular in the Middle Ages, and it was not uncommon for these accounts to feature descriptions of cannibalism. Two of the most important travel narratives for our concerns are those of Marco Polo and John Mandeville. Columbus read both of their works and to varying degrees used them as guides for his own explorations. Polo’s writings helped Columbus to determine what he believed to be the circumference of the Earth (he turned out to be quite wrong).38 More important, however, it was Polo’s writings that kept Columbus searching for Cathay (China), Cipangu (Japan), and the Great Khan. Just as Columbus’s quest was shaped by Polo’s own journey, so too did Polo impact discourses of cannibalism.

The travelogue of Marco Polo remains one of the most enduring narratives of the later Middle Ages. The Travels were actually written down by Rustichello of Pisa, who shared a prison cell with Polo in Genoa in the late thirteenth century. The work itself is a blend of travel narrative, fantastic history, and romance. Polo traveled much of the known world, from Acre to Beijing around the Indian peninsula and back to Constantinople. He traveled to the seat of Mongol power and met with Kublai Khan, who asked Polo, along with his father and uncle, who traveled with him, to carry a letter to Pope Clement IV requesting an official delegation of Christians. Polo’s opinions on the peoples he encountered range from outright disgust to measured admiration.

Alongside marvels of ingenuity, wealth, and engineering, Polo’s narrative discusses marvels of custom, behaviors that were decidedly outside the norms of Roman Catholic societies. He was fascinated in particular by women’s sexual licentiousness. In the majority of cultures he discusses, women are depicted as either chaste and modest or overly passionate and without shame. He describes the women of Cathay as “excel[ling] in modesty,” which profoundly shapes their lives. These women go to great lengths to preserve their hymens (and thus the assumption of their virginity): “The maidens always walk so daintily that they never advance one foot more than a finger’s breadth beyond the other, since physical integrity is often destroyed by a wanton gait.” He was fascinated and appalled by the range of sexual practices that he heard about on his journey. In central Asia he met a group of people whose notions of hospitality went well beyond acceptability in Polo’s mind. When a stranger arrived, the host was warm and welcoming, offering his house, and his wife, to the guest. The host then departed for several days, leaving the guest to do “what he will with her, lying with her in one bed just as if she were his own wife; and they lead a gay life together. All of the men of this city and province are thus cuckolded by their wives; but they are not the least ashamed of it. And the women are beautiful and vivacious and always ready to oblige.” A lack of “proper” attitudes regarding gender and sexual norms was enough for Polo to describe a group of people as “liv[ing] like beasts.”39

The first reference to anthropophagic practices in the Travels comes from a description of religious leaders in Tibet and Kashmir. According to Polo, holy men in these regions are filthy and have “no regard for their own decency or for the persons who behold them.” They are so physically and spiritually abhorrent that they eat the corpses of convicted criminals (but never those who die a natural death). In a region of China subject to the Great Khan, Polo tells of a group of bloodthirsty people who “relish human flesh,” whose armies are devoted to killing men for their feasts of flesh and blood. However, it was not until Polo and his companions arrived in the South Pacific that he reported extensively on the presence of monstrous humans and cannibals. Residing on islands between India and Japan is a group of people who kidnap all strangers to ransom them for money. If their ransom demands are not met, however, they kill and consume the captive in a great feast, for “human flesh they consider the choicest of all foods.” One might question why these people bother with ransom demands if human flesh is their favorite delicacy, but perhaps Polo is implying that their greed supersedes their unnatural anthropophagous appetites. He refers to this group as idolaters (which in this case implies that they are pagans of some sort), but near Java, Polo describes an island on which people living in the cities are Muslim and those in the country are pagan. The people who reside in the mountains “live like beasts,” eating human flesh and other unclean animals, and they worship “whatever they see first in the morning.”40 While Polo certainly has no great love for Islam, he does believe that Muslims are less “savage” than believers in animistic religions.

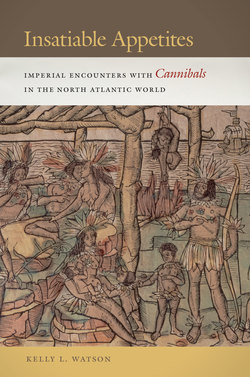

Figure 1.1 “Dog-headed cannibals on a Caribbean island.” Hand-colored woodcut. In Lorenz Fries, Uslegung der Mercarthen oder Cartha Marina (Strasbourg, 1525). This image of the Americas closely resembles Marco Polo’s description of cynocephali in Southeast Asia. (Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.)

There are fewer references to monsters, monstrous humans, and other supernatural marvels in the Travels than one might expect. Polo is skeptical about some accounts, reporting that the Pygmies supposedly brought back from India are in fact elaborate frauds created from monkeys. However, he readily accepts more dubious creatures, such as unicorns. He describes people who have tails “as thick as [a] dog[’s]” but are not covered in hair, as he expected.41 The most well known of the creatures that Polo encountered are the dog-headed men who supposedly inhabit the Andaman Islands.42 He describes them as idolaters who live like beasts, but more remarkably “all the men of this island have heads like dogs, and teeth and eyes like dogs; for I assure you that the whole aspect of their faces is that of big mastiffs. They are a very cruel race: whenever they can get hold of a man who is not one of their kind, they devour him.”43 Not only are the residents of the Andaman Islands cynocephalic, but they are also man-eaters. The question of whether or not they are fully human is important, for cannibalism implies the consumption of the same species; a dog that eats a human being is not a cannibal but simply a man-eater. If we are to accept that humans come in a variety of physical forms, including with the heads of other animals, then the Andaman Islanders are guilty of consuming their own species. However, if we discount the possibility of diverse humans forms, then the Cynocephali are a different species altogether and so cannot be the recipient of moral condemnation for their act.

The dubious fourteenth-century travel narrative of Sir John Mandeville also describes the “evil customs” of lands to the east. It is likely that Mandeville never actually existed but was a character created by an unknown individual. Yet his travelogue was enormously popular and appealed to the desires of some literate Europeans who wished to retake Jerusalem and continue the Crusades. Far more copies of his narrative survive than Polo’s; it remained a best seller well into the sixteenth century and was especially popular in England. The work itself drew from the writings of other travelers, Crusader histories, general chronicles, and encyclopedic works. Mandeville describes women who transform into dragons, give birth to snakes, or reside in women-only lands. He also writes about people in Africa with feet so large that they can be used like parasols, and giants, Cyclopes, and centaurs in Asia who are the offspring of human women and demons.44 Following the patterns of the sources he drew from, the author of Mandeville’s travels indicates that the farther one travels from Europe, the more marvels one will encounter but also the more riches and natural resources the lands will possess. It seems that the lands occupied by the most monstrous beings were often the richest.

Similar to Polo’s work, much of Mandeville’s Travels is devoted to reporting the gendered and sexual customs of the people he encounters. He describes widespread polygyny but also women who dress indecently or like men, and even one island where a class of men are charged with deflowering all brides on the night of their wedding to other men. In the land of the legendary Christian prince of India, Prester John, Mandeville finds uncommon virtue among vice, noting that Prester John has multiple wives but has sex with them only four times a year for procreative purposes.45

Unlike the true tales of Crusader cannibalism, Mandeville reserves his accusations of anthropophagy for non-Europeans only. His portrayal of the practices of the people of the Isle of Lamary presage many of the descriptors that European writers would later employ to depict American cannibals. The people of Lamary are described as unabashedly naked, promiscuous, and communalist. However, it was their practice of cannibalism that most astonished Mandeville: “In that country there is a cursed custom, for they eat more gladly men’s flesh than any other flesh. . . . Thither go merchants and bring with them children to sell to them of the country, and they buy them. And if they be fat they eat them anon. And if they be lean they feed them till they be fat and then they eat them. And they say, that it is the best and sweetest of all the world.” Not only are the people of Lamary cannibals, but they also trade in the flesh of children. Curiously, however, he explains that they do not wear clothes because Adam and Eve were naked, suggesting that the people of Lamary have some primitive understanding of Christianity. Beyond Lamary, and in fact beyond the entrance to Hell, another group of cannibals reportedly live ready to capture any unfortunate passersby. In addition to enjoying the flesh of men more “than any other flesh,” these people were supposedly twenty-eight to thirty feet tall. Mandeville also tells a tale about a group of priests in the lands beyond Prester John’s country who disarticulate the corpses of people and feed most of the remains to birds. The head is reserved for the son of the dead man, who takes it home and serves it to his friends and family during a great feast. He then uses his dead father’s skull as a drinking vessel.46 This story, along with many of Mandeville’s other tales of cannibals, come almost word for word from the less well-known fourteenth-century travelogue of Friar Odoric of Pordenone.47 The dog-headed cannibals are also mentioned in Odoric’s writings.48

Discursive Precedents for the New World

It may seem logical to dismiss cannibalism as an element of the past, something that we have moved beyond, but this ignores the contribution of cannibalism in constructing modern identity. Cannibalism is an inseparable feature of racism, colonialism, and sexism. The trope of cannibalism was employed by European writers as an important justification for the subjugation of peoples. It was the discursive presence of cannibalism, which was consistently linked to understandings of gender and sexuality, that indicated savagery long before race, as we understand it in the modern context, became fully developed.

When Portuguese caravels began exploring the African coast in the first half of the fifteenth century, they were in possession of technological advances that allowed them to travel farther and faster and to navigate more efficiently. These explorations and conquests, particularly in the Canary Islands, set the stage for the conquest of the Americas. The Spanish and the Portuguese first tested their imperial machines on Atlantic islands, subjugating people and establishing mercantilist ventures that would lead to unprecedented royal profits and a new thirst for expansion. Columbus did not decide in isolation to venture west to discover a new route to Asia; he was born into a rapidly changing world dominated by Italian merchants with a burgeoning desire to possess and consume the world’s resources. He was not simply curious about what lay to the west; he wanted to find riches and respectability there. He was driven by competing desires for gold, for glory, and for God. As we all are, Columbus was a product of his time. Born into a world on the cusp of modernity, he inherited intellectual legacies about the wonders of the far reaches of the globe from the medieval world, just as he possessed the mercantilist, empirical desires of early modern empires.

Medieval tales of cannibalism reveal a fascination with the unknown and a profound wonder at the diversity of the world. Cannibals were almost always portrayed as outsiders; whether they lived within the boundaries of “civilization” or somewhere far from European influence, they were Other. Travel writings demonstrate that the connections evident in classical discourse between sexuality, gendered norms, and cannibalism persisted. Even when a group of people was not explicitly described as cannibalistic, “improper” consumptive patterns went hand in hand with other supposedly deviant practices. For example, Mandeville describes a group of people on a far-flung island who have a wide array of edible animals available to them yet limit themselves to certain animals and never consume the myriad fowl or rabbits among them. These people “eat flesh of other beasts and drink milk. In that country they take their daughters and sisters to their wives, and their other kinswomen. And if there be ten men or twelve men or more dwelling in an house, the wife of everych of them shall be common to them all that dwell in that house; so that every man may lie with whom he will of them on one night, and with another, another night. And if she have any child, she may give it to what man that she list, that hath companied with her, so that no man knoweth there whether the child be his or another’s.”49 Mandeville places a description of their dietary habits right next to a report on their sexual and kinship practices. Taken together, this and other descriptions of exotic people in medieval travel narratives clearly demonstrate a pervasive belief in the connection between seemingly disordered sexuality and eating habits. Not only were other humans the most improper food to eat, but cannibalism was perceived as both gastronomic and sexual.

In addition to the concept of Otherness and the connection between sex and cannibalism, medieval narratives reinforce the link between anthropophagy and imperial expansion. From Herodotus to Marco Polo, the concerns of empires, city-states, and rulers were intimately tied to the accusations of cannibalism. As empires and cities grew and expanded, they came into contact with new groups of people, many of whom resisted foreign influence. The peoples inhabiting the areas to the north and east of the Black Sea proved to be formidable obstacles to both Hellenic and Roman expansion. For centuries these Scythians were also considered to be the consummate cannibals. In one way or another all of the accusations of cannibalism discussed herein are connected to the expansion of empires and cultures but not always outright conquest. Thus even though Columbus did not sail west with an army at his back, he did bear with him a millennium’s worth of axioms about Otherness. Well before any documented interactions between Americans and Europeans, including Vikings in Newfoundland, new lands and strange new peoples were quite often already believed to be savage and cannibalistic. The categorization of the peoples of the Americas, setting aside any evidence of anthropophagous practices, was perfectly consistent with European expectations.