Читать книгу Insatiable Appetites - Kelly L. Watson - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

I think there is nothing barbarous and savage in that nation, from what I have been told, except that each man calls barbarism whatever is not his own practices; for indeed it seems that we have no other test of truth and reason than the example and pattern of opinions and customs of the country we live in. There is always the perfect religion, the perfect government, the perfect and accomplished manners in all things.

Michel De Montaigne, “Of Cannibals,” 1580

In his famous essay “Of Cannibals,” Michel de Montaigne argues that Western societies rarely judge other cultures on their own terms.1 Rather, in his estimation Europeans tend to project negative qualities onto others, so that the cultural practices they observe actually mirror their own faults. Montaigne uses the practice of cannibalism in Brazil to reflect on European civilization, arguing for a nuanced understanding of difference and a careful examination of cultural practices before declaring them barbarous.2

Despite the seriousness of his argument for cultural relativism, Montaigne was not without a sense of humor. He ends the essay with this clever line: “All this is not too bad—but what’s the use? They don’t wear breeches.”3 He jokingly suggests that any reason or intelligence possessed by Indians is negated by their lack of clothing. This phrase highlights the difficulties of the work that he asks of his reader: no matter how hard one tries, cultural assumptions are difficult to overcome.4 A lack of proper clothing was a common descriptor of savagery in medieval and early modern Europe, but Montaigne underscores the absurdity of this assumption. Simply because they did not don clothing, should Indians be assigned a lower place in the hierarchy of humanity? “Of Cannibals,” written in 1580, was an important essay and shaped intellectual thought about imperialism and cannibalism in Europe, but beyond that it also demonstrates the inevitable tensions that resulted when Europeans encountered cannibals.

In this same essay Montaigne argues that “our eyes are bigger than our bellies, and that we have more curiosity than capacity; for we grasp at all, but catch nothing but wind.”5 This phrase plays with the idea of cannibalism, as it defines the limitations of an incorporative epistemology of imperialism. Montaigne hints at the limits of European knowledge about the New World and its peoples as he denigrates the rapid processes of imperialism and colonialism. Europeans rushed forth into the New World, conquered its peoples, destroyed its cities, and exploited its landscape without a thorough understanding of what they were doing and why they were doing it. Montaigne’s passage depicts the European conquest of the Americas as greedy and impetuous. European powers claimed lands and divvied up resources successfully, yet as they grasped at everything, they ignored the wider implications of their desires.

Montaigne’s metaphor for European imperialism provides a useful way of thinking about the discourse of cannibalism and the ways this discourse aided in the establishment and maintenance of imperial power in North America. Early modern writers rarely connected the supposed acts of cannibalism that they described with the larger issues of imperialism, yet hierarchy, dominance, and power were implicit in every account. The desire of the writers to record the supposed atrocities of Indigenous Americans for an eager readership back in Europe masked the true power of anthropophagic accusations. Through their accusations of cannibalism European writers implicitly and explicitly argued that Indians were inferior. As these conquerors, soldiers, priests, and settlers documented their perception of Indian barbarity, they underscored their preexisting belief in their own superiority. However, following Montaigne’s warning that curiosity exceeded capacity, this book examines sources of cannibalism from a new perspective. Rather than taking descriptions of cannibalism in European accounts as either true representations of savage Indian acts or dismissing these descriptions as merely propaganda, I uncover the ways the imperial context affected the discourse of cannibalism represented in European texts as well as the ways the discourse of cannibalism changed the dynamics of imperial power in North America.6 More specifically I also investigate the subtle and often hidden ways imperial power was gendered and was instrumental in redefining gendered and sexual norms.

Insatiable Appetites reveals new insights into historical documents, arguing for a recentering of gender in the analysis of the discourse of cannibalism. Recent discussions of cannibalism have tended to focus on the connection between cannibalism, savagery, and race. However, in the early modern period European understandings of cannibalism and savagery were more closely linked with gender and sexuality. Imperial power depended on the assertion of European superiority and the assumption of Indian inferiority, and the discourse of cannibalism played a key role in these determinations. As conquest always involved the domination of bodies in addition to land and resources, it is imperative to acknowledge and scrutinize the way that conquered bodies were gendered. Cannibalism is an embodied act, and an investigation of the discourse of man-eating illuminates the development of early modern ideas about race, gender, and sexuality. There is a great deal of scholarship that examines the racialized and gendered discourses of empire and colonialism, but there is a dearth of scholarly work that develops these ideas in the early modern North Atlantic.

My focus is on the discourse of cannibalism in European records from approximately 1492 until 1763. The objects of inquiry are primarily written texts, although some discussion of the role of images in the establishment and maintenance of imperial power is advanced as well. Through an analysis of these sources, I interrogate the construction of the idea of the cannibal in European empires rather than the actual practice of cannibalism among the Native people of the Americas. Not only is it virtually impossible to uncover concrete evidence of Indigenous practices solely through European records, but the idea of cannibalism and its associations with savagery were significantly more important in imperial discourse than were the actual rituals of human consumption.

Historically the consumption of certain body parts and some methods of corpse ingestion were treated as different from cannibalism. Human bodies were widely used for medicinal purposes in early modern western European nations and their colonies. Mummified remains of ancient and sometimes more recent origins were commonly prescribed as a treatment for a wide range of ailments. Human blood was used to treat epilepsy in England into the middle of the eighteenth century, for example.7 While corpse medicine was ubiquitous, it was not without critics, including Montaigne himself.8 Yet the producers and consumers of corpse medicine were not viewed as savage, bloodthirsty man-eaters, indicating that not all acts of the consumption of human bodies were viewed in the same way. Rather it was the cannibal practices of exogenous others that were linked with savagery, barbarism, and heathenism.

Acts of man-eating are generally placed into two broad categories, endo- and exocannibalism, referring to the consumption of insiders and outsiders, respectively. These categories loosely parallel the distinction between funerary and warfare cannibalism.9 While the definition of cannibalism may seem quite clear at first glance, establishing the limits of what constitutes an act of cannibalism is actually quite complex. On the simplest level, a cannibal is a person who consumes the body of another human being. But how much of another person does one have to consume to be a cannibal? Does the accidental ingestion of bodily fluids, for example, make one a cannibal? Does it have to be an intentional act to constitute anthropophagy? Or, put another way, does the consumer have to willfully and knowingly consume human body parts to be a cannibal? Does the doctrine of transubstantiation make Roman Catholics cannibals? Is there a difference between consuming the bodies of those who have died and killing people in order to consume them? We could keep asking these kinds of questions ad nauseam, but ultimately what matters for my purposes is that all of the acts of man-eating discussed herein are linked with savagery.

Determining whether or not groups of people actually practiced anthropophagy is difficult and comes laden with thousands of years of inherited prejudices and inequities. To label a population cannibalistic has always been a strategy of defamation. Indeed even asking the question presupposes that one human consuming another has significance well beyond the fulfillment of nutritional needs, for one does not ask a question whose answer is meaningless. Thus the determination of anthropophagy reveals something about both the questioner and the object of inquiry. Modern-day descendants of purported cannibals in history often take umbrage at the characterization of their ancestors. This is quite understandable given the faulty and prejudicial historical records that scholars have relied on to make such determinations. In the particular case of historic accounts of Amerindian cannibalism, almost all records, with very few exceptions, were written by peoples bent on conquest, conversion, elimination, and/or control over those that they regarded as man-eaters. Yet denying the existence of the practice of cannibalism is itself a reinscription of European and Western-centric values. Furthermore both modern scholarship on cannibalism and the sources on which it relies have certain features in common, including “a schema of analyzing culture that does not easily admit the existence of a phenomenon that is Other without explaining that phenomenon as a totalized alterity or without totally explaining it away.”10 In other words, it is quite difficult to acknowledge the existence of cannibalism without passing judgment on the people who might have practiced it. How can we objectively acknowledge and interrogate a practice that is so wrought with preconceptions and obfuscation? There are no easy answers to this question, and we must tread carefully, paying close attention to our own prejudices and those of our sources. As this book focuses on discourse, most of the time it does not matter if an accusation of cannibalism is true; it matters more that the accusation had consequences and that it reflected the mentalité of the writer and his or her culture. This can feel rather unsatisfying as most people have an innate desire to know.

The act of man-eating (excluding corpse medicine) in medieval and early modern western European society was always associated with savagery and Otherness. Culturally sanctioned cannibalism threatened to destroy the basic foundations of Christian society, for if humans ate other humans, then they could not be easily separated from animals. The taboo against man-eating was in fact one of the key markers of civilization. For European writers, the failure to recognize the boundaries between human and animal, and the refusal to value the lives of humans above all other creatures, was an indicator of savagery and primitiveness. Civilization created order out of chaos, and the presence of cannibalism served as a reminder of the barbarity from which all humans supposedly emerged. Even more than other subjects dealt with in European sources, descriptions of cannibalism were particularly prone to exaggeration and projection.11

Whither Cannibalism?

European writings about cannibalism can help us to understand the development of racism, patriarchy, and heterosexism in colonial and postcolonial contexts. An analysis of cannibalism is certainly not the only way the connections between gender and empire can be examined, yet the prominence of descriptions of cannibalism in European discourse demonstrates its importance. European men—and almost all of the pertinent writers were male—were captivated by the acts of cannibalism that they claimed to have discovered among the peoples of the Americas, and because of this they wrote about them often. Their descriptions reveal both a fascination with and revulsion for anthropophagous acts. The specific relationship between the discourse of cannibalism and the gendered nature of imperial power changed depending on the geographic, temporal, and imperial context. Due to the sheer volume of Western writings about cannibalism, savagery, and empire during the past five hundred years, this book cannot hope to cover every discussion in every moment. Instead I have chosen to focus on four distinct times and places in order to open up a conversation about the relationship between cannibalism, gender, sexuality, and race within the confines of empire and to establish a model through which we can better understand the nature of imperial expansion in North America.

Most scholarship that has discussed cannibalism, whether as an actual occurrence or as a discursive construction, has tended to focus exclusively on Latin America, and Brazil in particular. To date only modest consideration has been given to the study of cannibalism in North America. The extant sources dealing with cannibalism in North America are primarily concentrated in the following regions: the eastern seaboard of what is now the United States, southeastern Canada, the Great Lakes region, the American Southwest, Florida, the Caribbean, the Yucatán peninsula, and the Valley of Mexico.

In Dangerous Liaisons: Gender, Nation, and Postcolonial Perspectives, Anne McClintock writes, “The representation of male national power depends on the prior construction of gender difference.”12 In this way the nationalist masculine power of the nineteenth century and beyond depended on an earlier articulation of gender and power. Thus an examination of gender in the early modern world is essential for understanding the foundations of modernity. Following this assertion, Insatiable Appetites develops a theory of gender and empire through an exploration of the origins of masculine imperial power. In order to understand the institutions of patriarchy and racism in colonial or postcolonial situations, it is necessary to first interrogate the origins of such ideas. From where did the notion of gender difference that McClintock insists is a necessary precedent for masculine national power come? By examining the discourse of cannibalism in the conquest period of Atlantic North American history, the role that cannibalism played in the formation of European ideas about gender difference, sexual mores, and racial hierarchies is made clearer. As Ann Laura Stoler argues, we must place “questions of homo- and heterosexual arrangements and identities not as the seedy underbelly of imperial history . . . but as charged sites of its tensions.”13 Thus the fundamental anxieties on which imperial power rests are illuminated through an interrogation of the ways gender and sexual norms came to be within the confines of empire in North America. Implicit within ideas about barbarism in the early modern world was the inability of barbarians to conform to the established norms of gendered power and sexual practices. Cannibalism, then, existed alongside the perception of other inappropriate cultural practices in the writings of European men. The formation of masculine and, later, racist imperial power insisted on the perceived presence of cannibalism. In the early centuries of conquest, cannibalism above all else determined savagery, and savagery established one’s place within the hierarchy on which civilization and imperialism rested.

An important aspect of the colonial project was the insistence of the colonizers on control of the bodies of the colonized. The body itself was a fundamental site on which imperial power was negotiated and enforced. Sexuality was one essential realm through which control was maintained; the threat of pollution through miscegenation was a common fear expressed by colonizers. The body became a permeable border through which an early form of biopower was enacted.14 But while bodies were sites for the enforcement of imperial control, they were also sites for subversion. In the history of the Americas, the body was a contested space. Imperial power was enacted on the body, even while the body remained a space for resisting this power. The functions of the body had to be controlled and regulated in order for civilization to prosper. Thus the threat of uncontrollable bodies loomed large in the minds of early writers. The act of cannibalism signified an inability to control the body, where its victims were violated through penetration, ingestion, and incorporation. Cannibalism represented bodies out of control—bodies that functioned outside of the regulatory norms of Western Christendom. Because of this the fear of cannibalism was also a fear of alternative notions of embodiment.

Implicit within colonialist discourse is the assumption that the binary construction of civilization versus savagery and barbarism defines and constrains the world. While the definitions of civilization, savagery, and barbarism are variable, the European perception of cultural superiority was constant in the early modern Atlantic world. This was especially evident in commentary about norms of gender and sexuality. Europeans, most especially in the earliest years of contact, recorded Americans violating these norms with practices such as polygamy, serial monogamy, and promiscuity. Native communities often maintained political, social, and kinship networks that seemed at odds with European ways. Women’s participation in warfare and government, the ease of divorce, the prohibition of interclan marriage, and looser restrictions on women’s sexuality, among others, served as evidence of barbarism and thus inferiority.

Together the early European texts about the Americas, and the images they inspired, demonstrate the depth and complexity of discourses about cannibalism and encounter. What has been left out of much of the scholarly discourse on cannibalism to date is the role that gender played in labeling a group cannibalistic and in the consequences of this label. The cannibal was, and continues to be, simultaneously a racialized and gendered figure. In the period I discuss, ideas about both race and gender were not static. However, this did not preclude the existence of understandings of racialized and gendered difference. The distinction between what is race and what is racialized difference is slightly muddy; however, the key distinction in terms of this book is that, in general, European writers in the late fifteenth through the mid-eighteenth century did not directly equate skin color and other physical characteristics, which would later become descriptors of “race,” with inferiority.15 Rather Europeans understood the differences between themselves and the Indians they encountered in the Americas in ways that also took into account geographic, religious, cultural, and gendered elements. In other words, Europeans did not consider the variances in physical appearance between themselves and Indians to be the primary indicator of Indian inferiority. Rather European men justified their perception of their own superiority over Native peoples through a range of complex indicators, including but not limited to geography, religion, culture, and norms of gender and sexuality.16 Skin color did not serve as a straightforward heuristic that indicated savagery in this period; rather the determination of the savagery of a group of people relied on assumptions about proper human behavior and beliefs coupled with physiognomy.

The binary construct of civilization/savagery provides a clearer framework for understanding the ways Europeans articulated difference and otherness. The term savage encompassed a range of behaviors, beliefs, and assumptions about Others and was used by European writers to describe those behaviors, beliefs, and actions. However, both civilization and savagery were variable terms, and writers indicated that there existed degrees of each. For example, the seventeenth-century French writer Pierre D’Avity listed what he believed were the five indicators of brutishness: the inability (or refusal) to use reason, a savage diet, nakedness, poor quality of shelter, and a lack of government.17 Possessing these characteristics indicated that a particular group of people was suitable for conquest.

Race, as expressed through an understanding of physical and phenotypical characteristics that represented moral worth, social standing, and intellectual potential, would play a much more important role in the discourse of cannibalism in later centuries. By the nineteenth century the connection between emerging ideas of scientific racism and cannibalism was firmly established. In the period I discuss, gender was of greater importance to the discourse of cannibalism and was central in determining the effect that such discourse had on imperial power dynamics. Within the complex set of indicators of savagery and civilization, understandings of gender and gendered practices were fundamentally important for Europeans in establishing the place of a particular group within the hierarchy of human beings. Civilization itself was viewed primarily as a gradual process of cultural, social, religious, and intellectual developments. Therefore the so-called savage peoples of the Americas were seen as inferior and primordial and their understandings of sexuality and gender were viewed as equally atavistic and dangerous. For Europeans the figure of the cannibal hearkened back to an earlier era, a savage time that had been all but eliminated by the march of civilization. When these conquerors encountered “real live” cannibals, it was easy to see them as holdovers from the past.18 Furthermore not only were the conquerors truly men, but they had complex understandings of Native peoples as feminized and as failed men.

My decision to focus on the “discovery” of America in 1492 should not be taken as an acceptance of this date as the first European interaction in the “New World.”19 Nor should it be taken as an acceptance of the great historical division between premodern and early modern, as such divisions are always messy and fraught with assumptions. The shift from medieval to modern did not occur in a moment, and medieval ideas and traditions played an important role in the early modern world. The discovery of the Americas by Columbus did not, as is often repeated, spur an immediate rethinking of historical processes.20 Rather the “discoveries” made by Columbus set events in motion that would eventually radically reshape the histories of both Europe and the Americas. There is no specific year that clearly distinguishes the colonial from the nationalist period of North American history, as different parts of this vast landscape were colonized at different times and European imperialism did not end in one fell swoop; however, the end of the Seven Years War in 1763 provides a satisfying conclusion to this book.

The Treaty of Paris, which ended the Seven Years War, did not signal a complete end to European imperial expansion in the Americas. However, it did radically reshape the balance of power between France, Spain, and England in North America, greatly reducing the power of France and increasing that of England. Furthermore as the English became the dominant power on the eastern seaboard, groups of Indians, such as the Iroquois, were less able to play European groups against one another and carve out an influential space as middlemen, gatekeepers, and trading partners. Additionally, after the American Revolution, tales of cannibalism decreased rapidly in the eastern United States and were common only on the western frontiers. Thus the “triumph of civilization” in eastern North America meant that cannibalism ceased to be an important trope through which alterity was negotiated in that specific context. The firm establishment of imperial power in the Caribbean, Mexico, New France, and New England also led to the decline of writing about cannibalism. It seems that once the tangible threat of contact with savagery was eliminated, cannibalism was no longer an important topic of discussion in a particular region. Rather accusations of cannibalism lodged against Native peoples traveled along a moving imperial frontier. For example, in the nineteenth century accusations of cannibalism were much more often lodged against Africans as Europeans raced to carve up that continent for themselves.

The texts examined in this book come primarily from the late fifteenth to the eighteenth century as I compare and provide general findings about cannibalism and empire. In this vast swath of time, from “discovery” to the Seven Years War, Europeans writing of the New World witnessed and reported on the presence of cannibalism, enabling us to document the changes in these discourses over time.

Most academic scholarship on cannibalism has been written by anthropologists and literary theorists, although historians have not been completely silent. The works of such literary theorists as Tzvetan Todorov and Frank Lestringant have proven quite useful for their rich interpretations of the literature of conquest. Todorov’s The Conquest of America: The Question of the Other is a linguistic and semiotic analysis of the ways Europeans constructed Indigenous Americans as Other and an investigation of the effects of this imbalance of power. Although Todorov focuses primarily on the Spanish conquest of the New World, his ideas about Otherness resonate in other contexts as well. Frank Lestringant’s Cannibals: The Discovery and Representation of the Cannibal from Columbus to Jules Verne is notable for its focus on how the idea of the cannibal impacted European thought. Lestringant documents the changes in European understandings of the figure of the cannibal over time in order to demonstrate its continued importance. Like Todorov, Lestringant primarily restricts his investigation to Central and South America. Furthermore he engages with the idea of the cannibal in the works of important French literature and philosophy.

Scholars of psychoanalysis have also taken an interest in cannibalism as a cultural phenomenon. In Cannibalism: Human Aggression and Cultural Form, Eli Sagan argues that cannibalism, as both a fantasy and an actual practice, stems from sublimated aggression. The psychoanalyst Melanie Klein provocatively argues that cannibalism is one of humanity’s basest desires and that during infancy children must learn to effectively sublimate their desire for the consumption of the Other or risk developing psychological problems in later life.21

The use of psychoanalytic insights by literary scholars is quite common. The work of Maggie Kilgour, for example, examines cannibalism as a trope through which writers negotiate opposition between forms, such as inside and outside, consumer and consumed. The act of incorporation, which is at the center of all acts of cannibalism, is something to be both feared and desired, according to Kilgour. In this way cannibalism in literature reveals the primary tension between Self and Other.22 Kilgour’s work is featured in an interdisciplinary collection entitled Cannibalism and the Colonial World, which includes the work of other key researchers of cannibalism.23 Together these essays trace the idea of cannibalism from the colonial to the postcolonial world, from literal acts to metaphor, and demonstrate a wide array of approaches to the study of cannibalism, although with a limited discussion of North America. Peter Hulme, who coedited Cannibalism in the Colonial World, and the anthropologist Neil Whitehead are among the most important scholars of Carib cannibalism, and anthropophagy in general.24 Whitehead’s careful reporting on the evidence of Carib cannibalism in European records is especially useful.

Anthropological studies of cannibalism can be grouped into several categories, all of which assert that cannibalism is reflective of larger cultural factors. Psychoanthropology, a branch of the field that examines culture through the lens of psychoanalysis, typically articulates cannibalism as a manifestation of internal psychological processes. Cultural materialist anthropologists, such as Marvin Harris, believe that cannibalism can be best understood as a response to environmental factors: an inadequate protein supply for example.25 The well-known structural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss asserted that one of the fundamental binaries on which all human cultures rest is the division between the raw and the cooked. This division plays out in a number of ways, including nature versus culture and civilized versus savage. He further argued that within the act of cannibalism, the way a body is cooked reveals important insights into the social status of the deceased person as well as about the society as a whole.26 He argued that the boiling of bodies is the typical form of endocannibalism, and roasting is typical of exocannibalism; that is, outsiders are most like to be roasted, and in-group members are more likely to be boiled.27 In his framework cannibalism is a feature of “primitive” societies, a kind of disordered consumption that is opposed to civilization and culture. Another fundamental human distinction for Lévi-Strauss and other structural anthropologists is the divide between men and women. Thus humanity is in a constant tug of war between two opposing forces, with cannibalism residing squarely within the primitive, savage, and feminine side of the binary.

The anthropologist William Arens continues to be a polemical figure in the study of cannibalism. In his controversial book, The Man-Eating Myth: Anthropology and Anthropophagy, he argues that there has never been a society that has positively sanctioned cannibalism.He operates under the assumption that all of the evidence for cannibalism was merely propaganda to support European imperialism and served only to emphasize the “primitiveness” of conquered peoples. However, the majority of modern anthropological scholarship agrees that many groups did in fact practice cannibalism.28 What is often misunderstood about Arens is that he does not categorically deny the existence of cannibalism; rather he argues that whether or not cannibalism was a real social practice, it existed as a discursive trope. He asserts that the real or imagined existence of cannibalism does not diminish its importance in historical discourse.29

The ethnohistorian Thomas Abler confronts Arens in his article “Iroquois Cannibalism: Fact not Fiction” and debunks several of Arens’s assertions.30 Arens states that there is no definitive evidence of cannibalism in the Jesuit Relations, the compilations of reports from missionaries, which I discuss in greater detail in chapter 4. However, as Abler adroitly points out, thirty-one volumes contain references to cannibalism.31 Certainly the mere preponderance of references in the Jesuit Relations does not prove that the practice actually occurred, but when viewed in concert with the evidence for Iroquois cannibalism in speeches and captivity narratives, it is quite clear that anthropophagy did occur.

This project lends itself naturally to a comparative analysis; in order to draw conclusions about discourses of cannibalism in early postencounter North America, it is necessary to evaluate a range of sources from several imperial contexts, in addition to the social and cultural traditions of the Native group in question. D. W. Meinig’s characterization of the Spanish conquest as “stratification,” the French conquest as “articulation,” and the English conquest as “expulsion” serves as a useful model.32 The means and goals of empire had consequences not only for the frequency of reports of cannibalism but also in regard to the power of such reports in propelling conquest and colonization.

In American Pentimento: The Invention of Indians and the Pursuit of Riches, Patricia Seed argues that the way the empires of England, Portugal, Spain, and France conceived of ownership of land, resources, and people shaped the development of imperial power in the Americas. For example, the Moorish influence on Iberian political thought after the Reconquista created the understanding that deposits of natural resources were put there by God for use by his people. The successful elimination of Muslim power in Spain was seen as proof by the monarchs and other elites that Spaniards were the true people of God, and therefore the resources were theirs for the taking. Spanish tradition also insisted on the payment of one fifth of all profit to the Crown. This complex understanding of public versus private ownership carried over into the issue of slavery. Seed argues that although the Spanish Crown expressed no concern about the coercion of Native labor in the pursuit of riches, Indian slavery was not condoned because it implied private ownership of labor and resources.33 The development of the repartimiento system reflected this, as it apportioned Native labor into private hands in a trustee relationship, not full ownership.34 Spaniards in general believed that the pursuit of riches was a common goal to benefit all of God’s people. The control of natural resources obtained by the exploitation of Indian labor was of primary importance to the Spanish Empire in the Americas.

Drawing on Seed’s insights, I argue that the ways a particular empire understood its relationship to land and Others was important in determining the place of cannibalism within discourse. For example, as Spaniards perceived the exploitation of natural resources as central to their imperial goals, they were more likely to carve out a subservient position for Indians in order to maintain a local labor force. In chapter 2 I examine how the slave trade and the mining of raw materials were directly related to accusations of cannibalism. In opposition to Spanish conceptions, Englishmen conceived of their efforts in the New World in more individualized ways and were far more interested in private landownership.35 While success for the conquistadors may have been measured in gold and silver, success for the English was measured in landownership.36 Based on these general priorities, the English colonists in North America tended to show less interest in affording Indians a space in their New World. Thus the prominence of cannibalism within English discourse, and the relationship between cannibalism and imperial power, differed from the Spanish and French versions and had consequences for the gendered nature of imperial power.

In order to understand the discourse of cannibalism (keeping in mind imperial context), it is necessary to understand the distinction between civilization and savagery and to acknowledge the power of this binary. The conquest of the New World rested on the assumption of a fundamental difference between the European and the Indian. No matter how profoundly different European ethnic groups believed in their own regional and cultural superiority within Europe itself, they nonetheless believed in the innate superiority of Christian Europeans over all others. Certainly the English believed, for example, that Catholicism was fundamentally flawed, but they nonetheless continued to operate under the assumption that a flawed belief in God was superior to no belief in God at all. In order to make the conquest of the Americas viable, Europeans had to see themselves, and their social and cultural traditions, as different from American ones.

Anthony Pagden discusses many of the heated Spanish arguments about Indian humanity in The Fall of the Natural Man. He demonstrates that mainstream Spanish thought came to recognize the shared humanity of Spaniards and Indians, even if Spaniards considered Indians to be inferior. They assumed that it was their job to provide Indians with the knowledge that was denied them by their fall from grace. Spanish thought presumed that one of the most fundamental tenets of humanity was that humans should not consume one another. God called humanity forth to prosper, populate, and control the world through his word and glory; consuming one another violates his divine will. A similar sentiment was echoed in other empires as well, and although the English and the French may have had different ideas about God and about their relationship with the land and peoples of the New World, they still believed that human consumption violated fundamental tenets of Christianity.

The modern concept of the Other is useful here. While it is difficult to provide a concrete definition of this term, in its simplest form Others are those who represent the opposite of the Self/Subject. The Other serves to provide a Subject with a point of reference for something it is not and must strive not to be. Although the Other represents what a society should not be, there is also often a fetishistic reverence for the Other. It stands in opposition to the Self, the Subject, the Signifier. In order to define itself, a being must determine what it is not. The Subject is not merely constructed in opposition to its Object, however, as the reverse is also true. The “civilized” being exists because of the cannibal, just as the cannibal takes form because of the existence of the civilized world.

In The Location of Culture, Homi Bhabha puts forth a methodology for the analysis of the Other in discourse: “My reading of colonial discourse suggests that the point of intervention should shift from the ready recognition of images as positive or negative, to an understanding of the process of subjectification made possible (and plausible) through stereotypical discourse.”37 The cannibal was a key site for mapping subjectification for European writers, as the opposition between presumed American cannibal savages and civilized Europeans became a fundamental trope through which early modern ideas about identity, and especially masculinity, were formed. While there are texts that are more “sympathetic” to the cannibal, for most the cannibal is the supreme representative of savagery. To oversimplify the matter slightly, it was not because Native peoples were cannibals that Europeans felt they needed civilizing, but that because they needed civilizing they must be cannibals.

Cannibalism versus Anthropophagy

It is important to separate the very real physical act of anthropophagy from the idea of the cannibal. The cannibal is a construct produced by imperialism and maintained through discourse. The image of the cannibal was the product of a complex set of interactions and assumptions. As Hulme argues, “To concentrate on the notion of a dialogue is to insist on two emphases, not always present in discussions of cannibalism; on the agency of those described as cannibals—difficult to access but necessary to posit; and on the relationship between describer and described, between Europe and its others. The figure of the cannibal is a classic example of the way in which that otherness is dependent on a prior sense of kinship denied, rather than on mere difference.”38 Thus in order to understand the idea of the cannibal, one must first understand the complex power dynamics inherent in interactions between Europeans and American Indians, as well as prevalent beliefs about alterity. Many sources reveal instances when Native peoples called Europeans cannibals and feared them for their cannibalistic reputation.39 What differentiates this kind of relationship is the imbalance of power between colonizer and colonized. This difference most clearly manifests in European dominance of the written record. The image of the savage cannibal Native has lingered and prospered over time; the figure of the bloodthirsty cannibal European, however, has not. Cannibalism still remains perhaps the most powerful and enduring image of savagery.40

Before moving forward into a description of the chapters to follow, I must present an idea that is fundamental to this work and any study of cannibalism. As some readers may know, the modern English words cannibal and cannibalism are the etymological descendants of word Carib. The Carib tribe, as I argue in chapter 2, in addition to having inspired the name of the Caribbean and the term that we now use to describe man-eating, was one of the main targets of European accusations of savagery. In discourse Caribs were placed in opposition to their supposedly more docile neighbors, the Arawaks. Despite the etymological relationship between Carib and cannibalism, the language employed in early works on the Caribbean to describe the act of man-eating and the people now known as the Caribs was quite complex, and it is not always clear if a writer is referring to the Caribs, to man-eaters, or to both. Columbus and others sometimes wrote about the Caniba, or people of the great Khan.41 Much important linguistic work has been done on the use of the words Caniba, Caribes, Carib, and others in early writings, but suffice it to say that while the meanings that Columbus and others attached to these words cannot be fully recovered, these early writings established a precedent in which Carib became equivalent to cannibal. However the modern word came to be, it is important to note that cannibalism and cannibal differ from the more formal descriptive terms anthropophagy and anthropophagite. Cannibals and cannibalism came to be associated with a whole host of other savage traits and bear a heavy discursive legacy.42 Anthropophagy, on the other hand, derives from the Greek and simply means human-eating. This book primarily examines cannibalism, not anthropophagy. I am not strictly concerned with acts of human-eating but rather with the development of the discourse of cannibalism and all of the historical and etymological baggage that this term carries with it. In fact there is a debate within anthropology as to whether or not the term cannibalism should be reserved for use “for the ideology that constitutes itself around an obsession with anthropophagy.”43 However, despite the important conceptual differences between these two terms, I use them interchangeably to prevent excessive repetition.

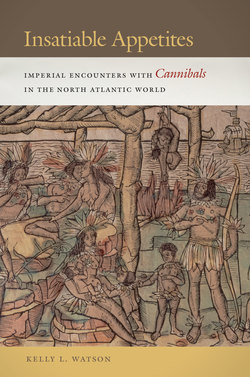

Figure I.1 “Allegorical image of America.” Engraving. Frontispiece in Ferdinando Gorges, America Painted to the Life the True history of the Spaniards proceeding in the conquests of the Indians, and of their civil wars among themselves (London, 1659). It was quite common for the American continents to be represented in allegorical form as a cannibal woman. (Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.)

The primary sources discussed herein were chosen based on a number of criteria. While there are some accounts in the historical record about Europeans consuming one another, especially in times of starvation or extreme stress, these are rare and remarkable.44 There are also numerous accounts of shipwreck cannibalism among Europeans, most famously in the wrecks of the French frigate Méduse and the English ship Mignonette.45 These occurrences were always dealt with differently in European texts than those perpetrated by Natives, as there was never the assumption of a cultural pattern of cannibalism. While starvation cannibalism was considered singularly abhorrent by some, as evidenced by Jean de Léry’s writings about the siege of the Sancerre in France in 1572–73, for example, it was nonetheless treated as a momentary aberration.46 The most prevalent type of cannibalism presented in European chronicles was performed by Native people on Native people. Less common, but still notable, were accounts of Natives consuming Europeans.

This book draws primarily from published works in part because of the popularity of accounts of cannibalism and exploration, but primarily because of its focus on discourse. Insatiable Appetites cannot claim to encompass every possible source that includes anthropophagous references; instead I focus on those that contain substantive references. The evidence discussed in the following chapters is limited to explicit references to cannibalism. I do not assume that the use of a term like bloodthirsty to describe Native peoples is an indicator of the practice of cannibalism, yet there was clearly a connection between the European conceptions of warrior bloodlust and the desire to consume human flesh. Finally, whenever possible, the sources discussed in this book are limited to observational accounts rather than strictly philosophical works, such as the writings of Montaigne.

The vast majority of sources examined in this book are available in English translation, and I have typically cited these versions for the ease of the reader and because of their widespread availability. The texts were originally composed in a range of languages, including French, German, Latin, Spanish, Italian, Greek, Old English, and Portuguese. I consulted original sources whenever possible, but for those texts in Greek, Portuguese, Old English, Italian, and German I was forced to rely exclusively on available translations. The translations were selected based on both publication date and widespread acceptance. For most of the sources that I read in translation only, I consulted several different versions. For example, Michele Cuneo’s essay discussed in chapter 2 was originally written in Italian, and the available English translations vary slightly. This was particularly noticeable in the translation of the phrase “una Camballa belissima,” which is variously translated as a gorgeous or beautiful, cannibal or Carib, woman or girl. Such choices obviously impact the interpretation of this key passage. Most translations use “gorgeous cannibal woman,” and as such I have chosen to do the same. While the use of translations undoubtedly impacts my interpretation of the sources, care was taken to ensure that the impact was as limited as possible.

Sources on cannibalism are not evenly distributed across empires. The Spanish records are by far the most extensive and are particularly strong on cannibalism in sixteenth-century Mexico. French sources yield a reasonable amount of information, and the records of Jesuit missionaries in the Great Lakes region are especially robust. English sources, however, are far more difficult to come by. These disparities in the historical record speak not only to the differences among the Native peoples encountered but also to the priorities of empire and the period in which considerable intervention occurred. Large-scale English efforts, for instance, occurred much later on the Atlantic seaboard and overall were far less interested in incorporating Native peoples into the Anglo-American world.

The chapters that follow are organized in chronological order, but each also explores the discourse of cannibalism from a specific subject position within an imperial and geographic context. For example, in the case of the French Empire in the Americas, I focus on the writings of Jesuit missionaries in Canada. The limited perspective of the Jesuits cannot be easily extrapolated to make conclusions about the French Empire writ large, but the uniqueness of the encounters between Catholic priests and the Iroquois can provide insight into the relationship between religion, the discourse of cannibalism, and imperial power. In this way no one chapter fully represents the discourse of cannibalism from the position of empire; rather together they speak to the ways in which the discourse of cannibalism was fundamental to the establishment and maintenance of European imperial power, in all of its manifestations, in North America.

The first chapter, “Inventing Cannibals,” provides an overview of the classical and medieval discourses of man-eating. Drawing from authors such as Herodotus, Pliny, Isidore of Seville, and Marco Polo, I demonstrate the place of anthropophagy within the literature of monstrosity and travel writing, as well as the role of cannibalism in the construction of Otherness. Ultimately I elucidate the intellectual heritage of European travelers to the Americas in order to shed light on the biases, heuristics, and preconceptions that they brought with them to the New World.

Chapter 2, “Discovering Cannibals,” investigates the emergence of the idea of the cannibal in the writings of European explorers of the Caribbean. Beginning with Christopher Columbus and continuing through to Amerigo Vespucci, I establish the development of the idea of cannibalism, as opposed to anthropophagy. The encounter between European men, who hailed from a variety of homelands, and the Caribs and the Arawaks was fundamental in creating the discourse of cannibalism. These encounters did not happen in a vacuum, and these writers drew explicitly from medieval and classical ideas. However, they also radically reshaped the power of the discourse of cannibalism. Furthermore in these writings the discourse of cannibalism was gendered based on preexisting understandings of gender, sexuality, and monstrosity. In these accounts European men expressed great fear about the cannibalistic appetites of Carib women, which reflected their fear of the unknown and its feminine nature.

In the context of the conquest of Mexico explored in chapter 3, the conquistadors expressed much less fear of the anthropophagous appetites of the women they encountered. They used accusations of cannibalism to justify their conquest of the Aztecs and to further the establishment of the superiority of Spanish masculinity. The descriptions of horrific sacrifices and cannibalism practiced by the Aztecs enabled Hernán Cortés and his men to argue for the superiority of Spanish civilization. Additionally, continuing a practice established in the Caribbean, these men connected cannibalism with savagery and assumed that people who practiced man-eating were also prone to sexual indiscretions. By calling them cannibals, they made the bodies of the Aztecs ripe for conquest. This conquest took place on the battlefield, but also in the bedroom. Cortés was the prototypical masculine imperial hero who exploited the bodies and labor of the Native women he encountered. His successes not only portended the erasure of the “abominable” customs of cannibalism and sacrifice among the Aztecs but helped to establish a stratified society in which power was masculine and women’s participation in political matters was voided.

Chapter 4 focuses on the discourse of cannibalism in New France, specifically through the documents of the Jesuit Relations. Unlike Cortés, Columbus, or Vespucci, the Jesuit missionaries did not arrive in North America desirous of the bodies of its inhabitants; they sought souls instead. As an avowedly celibate order, the Jesuits sought to prove their masculinity by enduring the trials of the wilderness and the cruelties perpetrated by the Indians, particularly the Iroquois. Their accounts of martyrdom and cannibalization at the hands of their potential converts not only drew more dedicated missionaries to Canada but also reiterated the seriousness and importance of their cause. The goals of the French Empire were less clearly articulated than their English and Spanish neighbors, and their settlements in the Americas were typically smaller and more distant from one another. The French sought to first establish economic relations with the Indians in order to profit rather than fully conquering and dominating the land and peoples. Thus the accusations of cannibalism in the Jesuit Relations spurred religious interest in the peoples of Canada rather than inspiring full-scale conquest.

Chapter 5 examines the discourse of cannibalism in the English Empire, focusing particularly on New England. Captivity narratives provide the richest source of references to cannibalism; however, English writers were far less preoccupied than the French and Spanish with man-eating in general. I argue that this is due to the legacies of Spanish and French efforts, the practices of the Native groups they encountered, and the particular goals of English colonization. The English were much less interested than the French or the Spanish in making space for Indians in their new empire. Captivity narratives demonstrate that discussions of cannibalism reinforced the development of a new understanding of Anglo-American masculinity that defined itself against the wilderness and its inhabitants. The ability to endure the threat of cannibalism and other trials at the hand of the Indians allowed the English to justify their presence in the Americas and assert their power over the lands and its people.