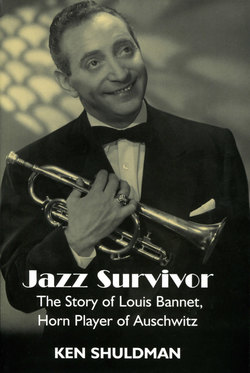

Читать книгу Jazz Survivor: The Story of Louis Bannet, Horn Player of Auschwitz - Ken Shuldman - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 2: Pimps and Whores, Laurel and Hardy

ОглавлениеAccording to Jewish law and tradition, thirteen-year-old Louis Bannet was now a man.

But on the streets of Rotterdam, he still wore short pants and leggings just like any other Dutch boy. This didn’t stop him from taking to the streets to look for work as a professional musician, however. He had heard from some older students at the Conservatory of a place down by the waterfront called Charlie Stock’s, a coffee house that doubled as a musician’s hiring hall. When he walked in carrying his violin case, he was probably too young to realize that musicians weren’t the only professionals available for hire at Charlie Stock’s. The place was filled with merchant seamen, Chinese laborers, musicians, many with their instruments spread out on tables, and women: women unlike any he had seen in the Helmerstraat. Their faces were painted with lipstick and rouge. Their dresses were brightly coloured, not the drab blacks and grays worn by his Jewish neighbors, and there was much skin on display. As Louis attempted to venture further into the crowded hall, he was stopped by a man who told him that minors were not allowed inside. As he was being escorted out, he caught the attention of a young man sitting at a table playing cards with several young women. He motioned for the man to bring the young boy over.

Aren’t you a little young to be in a place like this?’ the man asked.

‘I heard from some friends at school that this was the place for musicians to find work,’ Louis answered.

‘This is a place for a lot people to find work,’ the man said, looking around at the table of women. ‘My name is Hein Frank. And who are you?’

‘My name is Louis Bannet, and I play the violin.’

‘Well, Louis Bannet, if you plan on finding work here, I can tell you one thing: Charlie Stock doesn’t hire young boys. Come with me and we’ll at least try to make you look the part.’ (When Louis recounted this story for the first time for me, he was well into his eighties, and he was a little shy about admitting that Hein Frank was a pimp - and not just any pimp, he said, but a Jewish pimp.) Hein Frank took Louis to the back of the hall and down a long corridor past several rooms, all with their doors shut. Louis could hear the sound of men and women moaning and furniture creaking as he walked past the rooms. Hein opened the door to one of the rooms, quickly walked in, and in a few seconds came out with a pair of pants. He held them up to Louis and then asked him to try them on for size.

Louis slipped into the room to change, and walked out a man.

He didn’t get any work that first day, nor did he find any on the second or third. But he came back day after day, and quickly learned how the selection process worked. It seemed that Charlie Stock always chose the same people. When he asked Hein Frank about this, Hein said Charlie had a very simple credo: you pay, you play. Sensing Louis’ frustration, Hein paid Charlie Stock a visit; the next day, when a violin player was needed for a children’s birthday party, Louis got the job.

He had to wait weeks, though, to be called again. But when he was finally chosen, he was sent to a cinema to play in the orchestra as silent movies from America played on the screen. Louis loved this job because it allowed him to play all types of music with a group of accomplished musicians. He played for cowboy movies, swashbuckling pirate adventures and tear-jerking melodramas. His favorites, though, were the comedies, especially Laurel and Hardy. There was just one problem. Louis couldn’t stop laughing, and finally the theatre manager had to fire him because his laughter was distracting the other musicians. ‘He said to me, "I hired you to play, not laugh,"’ Louis recalled nearly eighty years later. He returned again to Charlie Stock’s, but new work rarely came his way. Louis couldn’t understand why it was so hard to get work. Eventually, Hein Frank hired him to do some bookkeeping.

How Charlie Stock’s came to be the place where Rotterdam’s musicians went to find work, Louis was never certain. What is certain is that it was a gathering place for the sailors and dockworkers who unloaded the ships that arrived from all over the world. One thing the sailors always seemed to have with them was music, especially phonograph records from London and America. Charlie Stock played these records on a player he kept on the bar, and the sailors danced to the music with Hein Frank’s girls. In fact, it was on one of those records that Louis first heard the music that would change his life.

‘I was sitting in Hein Frank’s office one day and I heard a sound that practically lifted me off my chair. I went out to the main hall and noticed a group of sailors standing by the record player. They were drinking and snapping their fingers to the music. I had never heard anything like it. I thought it was a trumpet, but I wasn’t sure, since I’d never heard a trumpet sound like that. The notes were bending and moving in all different directions. There was a drumbeat pounding out a driving rhythm. I saw the record cover on the table and written on it was the name Louis Armstrong.’

As the weeks and months passed, Louis’ prospects dimmed. Hein Frank had a simple explanation.

‘Louis, look around you. All you see are violin cases. There are probably more violin players in Holland than tulips. Have you ever thought of another instrument?’ he asked.

‘This is the only instrument I know,’ Louis answered. ‘But maybe it’s time to think of something new.’

Louis knew Hein Frank was right. But how could he tell his mother that he was giving up the violin?

Later that night, Louis lay awake in his bed waiting for his older brother Isaac to return from work. Isaac Bannet worked for their Uncle Abraham at his blanket factory. When he came home, he walked into the room, sat on the bed beside Louis’ and removed his shoes.

‘Isaac, I’m going to give up the violin,’ Louis announced.

‘What do you mean, give it up?’ Isaac replied.

‘There are too many violin players in this city and not enough jobs,’ Louis answered.

‘But what about all the years you spent at the Conservatory? What will Professor Bloorman say? What will our mother say?’

‘That’s why I’m doing it, for our mother, Isaac. I have to find a way to make more money so we can have more food on the table, so we can pay the rent, so the lights are not turned off every week.’

‘What will you play?’ Isaac asked.

‘Maybe a saxophone, I’m not sure. All I know is that I need 30 guilders for a new instrument.’

‘I’m sure Uncle Abraham would help you,’ Isaac said. ‘You should go and see him tomorrow.’

The next day Louis went to see his Uncle Abraham. When he walked on to the factory floor, the noise was deafening. As he walked passed the huge cutting tables, he saw his brother Isaac, who motioned him to climb the stairs to his uncle’s office on the second floor. Louis entered the office. His uncle was stooped over his desk, eating a bowl of soup and reading from a Hebrew prayer book.

‘My uncle was a very religious man,’ Louis recalled. ‘I tried to explain my problem to him, and I told him about the saxophone, but it seemed like he didn’t hear me. Finally, he put his spoon down and closed his book. ‘A saxophone,’ he said. ‘That’s not a very Jewish instrument.’ I told him that it had a shape like a Shofar. He reached into a desk drawer and pulled out a box. He opened it and counted out the thirty guilders. Before I left, he made me promise not to forget my violin, which I never did.’

Later that week, Louis went to Bommel’s Music Store. Even after more than seventy years, Louis remembered this visit quite vividly.

‘The walls of the music store were covered with a symphony’s worth of instruments. Mr Bommel, he had a terrible stutter, and when I came into his store with all this money he was very surprised. I asked him what kind of saxophone could I buy with thirty guilders. He said I couldn’t buy any saxophone with just thirty guilders. "Then what can I buy?" I asked. Mr Bommel walked to the end of the counter and reached for a trumpet. He said "For thirty guilders this is all I can offer you. Do you know how to play?" I took the trumpet and brought it to my lips and blew, but I couldn’t make a sound. He said "Your lips are cold - rub them with the back of your hand like this," and he showed me how.

So I rubbed my lips and again brought the trumpet to my mouth and I blew, and I made a loud sound that frightened some of the other people in the store. Mr Bommel said I had a healthy set of lungs, and he said one day people would pay to hear me play.’

As with the violin, Louis Bannet took to the trumpet quickly, and, thanks again to the generosity of his Uncle Abraham, he was able to study with a well-known teacher, Aaron DeVries, the patriarch of a very well-respected Dutch musical family. He also had another teacher - Louis Armstrong. Every chance he got, he would head down to Charlie Stock’s or one of the many music shops in Rotterdam and listen to Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five. One of the recordings he listened to over and over was the 1925 recording of St. Louis Blues, with the legendary Bessie Smith on vocals. He memorized it note for note, and practiced it so much that his neighbors must have thought they were living on Bourbon Street and not Katendrecht.

In 1929, as the world’s economy was about to tumble, Louis Bannet landed his first trumpet gig with a novelty jazz band called Anton Swan and the Swantockers. Anton Swan, a tall, lanky Dutchman more interested in getting laughs then getting people on the dance floor, dressed the band in silly sailor suits and fake mustaches. But he was smart enough to realize that in Louis Bannet he had a first-rate soloist who could play any song the audience requested. And as the band started playing the dance halls and clubs in Amsterdam and The Hague, the signs outside now read Anton Swan and the Swantockers, featuring Louis Bannet on trumpet.