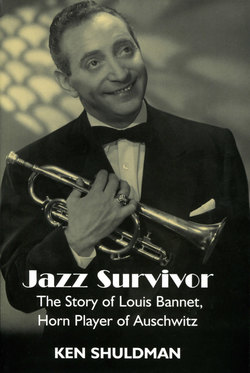

Читать книгу Jazz Survivor: The Story of Louis Bannet, Horn Player of Auschwitz - Ken Shuldman - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 3: All That Jazz

ОглавлениеWhen the great tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins left Fletcher Henderson’s band in New York and headed for Europe towards the tail end of 1934 he was like Louis Bannet, searching for a new musical environment. Arriving at the port of Rotterdam aboard the Ile de France, he had no idea what to expect from the Dutch jazz scene -in fact, he wasn’t sure if one even existed. But in truth, jazz was all the rage in Holland. Groups like the Ramblers, the Bouncers, the Swing Papas, and the Red, White, and Blue Aces were in full swing by the time Hawkins reached port. Though never quite approaching the level of play of their American heroes, many Dutch jazz musicians fared quite well, and what they lacked in ‘chops’ they made up with heart and humor.

The arrival of Coleman Hawkins in Holland was big news for jazz musicians and jazz fans. One of those young fans was an aspiring trumpet player and close friend of Louis Bannet’s, Pieter Dolk. Pieter knew that Louis was growing restless playing with the frivolous Anton Swan, so one night he took him to see ‘The Hawk’, Coleman Hawkins, at the Lido in Amsterdam. As Louis remembered, ‘Just about every jazz musician in Holland was there that night, many hoping to sit in.’ Hawkins ripped through a long set that included rousing renditions of Honeysuckle Rose, Avalon, and Stardust . For his encore, Hawkins announced to the crowd that he was going to play Tiger Rag, and invited any musician who wanted to play up to the stage. The first one to hit the stage was a Dutch drummer named Maurits von Kleef. Following right behind him was an extremely nervous Louis Bannet. Louis took a short, but spirited, solo. Drummer von Klaaf tore into his skins and brought the Dutch crowd to its feet. After the se t, Louis and Maurits went back to Hawkins’ dressing room. They jammed a little, but mostly talked and listened, as Hawkins regaled them with stories about some of the great players he had known. As a show of Dutch hospitality, Maurits introduced Hawkins to a Dutch drink made with egg yolks and brandy. Louis distinctly remembered that Hawkins’ second set was not as sharp as his first.

But that night was important for one other reason. It was the beginning of an enduring friendship. Louis had found a kindred spirit in Maurits von Kleef, as well as someone who could supply the backbeat to a band of his own. Over the next several months Louis auditioned musicians from all over Holland for his new five-piece band, and by the spring he had his line-up. There was Maurits von Kleef on drums, Dick von Heuvel on the vibraphone, Lex von Weuren on piano and Jac de Vries on bass and saxophone. After several months of rehearsals, Louis Bannet’s Rhythm Five made their debut at the Pschoor nightclub in The Hague. ‘I even remember the set list from that first night,’ Louis recalled years later in Toronto as he rattled off song after song.

‘I Only Have Eyes For You, Heebie ]eebies, After You’ve Gone, I’m In The Mood For Love, Dinah, Stardust, Blue Moon, Lazy River, Some Of These Days, I Can’t Give You Anything But Love, I Got Rhythm, I’ve Got The World On A String, Bugle Call Rag, Alexander’s Ragtime Band, Lullaby Of Broadway, One O’C lock Jump. The audience was great. For an encore, we came out and played St. Louis Blues.’ From that night on, it would become Louis Bannet’s signature encore song.

Over the next several years, Louis Bannet and his Rhythm Five played all across Holland and central Europe, traveling to Belgium, Germany and Switzerland. Louis also began to sing, winning warm applause for his booming tenor on such numbers as Blue Moon and I Only Have Eyes For You.

One night in the lobby of a Swiss hotel, a bellboy paged Louis and handed him a telephone. It was the manager of new club called Heck’s Cafe, which was set to open in a few months in Amsterdam. The manager said Mr Heck wanted Louis Bannet and his Rhythm Five to headline on opening night. The following week, the band headed back to Holland to begin rehearsals-for the opening.

One evening while on a break from rehearsals, Louis and the band were visited by an old friend, Hein Frank, along with some of his female companions. Louis hadn’t seen Hein in several years. Hein said he was following Louis’ career and even felt a sense of pride - after all, he was the one who had suggested Louis pick up another instrument. One of Hein’s girls requested a song, something by Louis Armstrong. Louis picked up his horn and led the band in The Devil And The Deep Blue Sea. He sang not like Louis Bannet, but like Louis Armstrong. His impersonation was uncanny, and Maurits suggested he try it out in front of a larger audience. So that weekend at a performance at the Pschoor nightclub, Louis repeated his impersonation: the audience went wild. The next day in a review of the show, a newspaper writer praised the performance and crowned Louis ‘the Dutch Louis Armstrong’.

Ironically, around this same time, Louis Armstrong himself was embarking on a tour of Europe. He had shows planned for London, Denmark, Paris, and Belgium. The last stop on the tour would be Amsterdam.

Two weeks later in Rotterdam, Leentje Bannet was sitting in her kitchen with her son Isaac. As Isaac leafed through the newspaper, he came across a picture of his brother Louis in an advertisement announcing the grand opening of Heck’s Cafe. He showed it to his mother and suggested that he escort her on opening night and that they keep it a surprise. Leentje Bannet had never seen Louis perform with his band. In fact, the last time she had seen him play was when he performed at Queen Wilhelmina’s birthday celebration at the Conservatory. On the night of the Heck’s Cafe opening, she put on the dress she usually wore for Rosh Hashanah. She and Isaac were given a table by the front of the stage. As the lights were dimmed, a spotlight hit the stage and the Rhythm Five took their places. Finally, Louis walked out on to to the stage to a rousing ovation. ‘I looked out at the audience and welcomed everyone to the club. I noticed my brother waving to me, and then I saw my mother sitting beside him. I said, "Ladies and gentlemen, I was going to open with an Armstrong song, but I hope you don’t mind, my mother is sitting right over there and I’d like to play a song just for her." So I picked up my trumpet and played My Yiddishe Momma.’

The next morning, Louis joined his mother and brother for breakfast. Isaac opened the newspaper to a review of last night’s show at Heck’s and read it aloud. The writer ended his story by saying that ‘Louis Bannet, the Dutch Louis Armstrong, has a beautiful future ahead of him.’

Several weeks later, Louis was in his dressing room at Heck’s. ‘It was the last night of the engagement,’ Louis recalled. ‘The stage manager knocked on my door. I heard this deep, raspy voice ring out. "So you’re the Dutch Louis Armstrong. Well, it’s nice to meet you: I’m the American one." It was Armstrong himself. It was fantastic.’ They took out their horns and jammed. At one point, Armstrong proudly showed Louis the Jewish Star of David he wore in honor of the Karnovskys, a Russian-Jewish family he worked for as a child in New Orleans, who provided the funds for his first cornet.

The Dutch Louis Armstrong would soon be wearing a Star of David of his own, although it certainly couldn’t be called an honor.