Читать книгу One Arrow, One Life - Kenneth Kushner - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Entering the Way

At first glance it must seem intolerably degrading for Zen—however the reader may understand this word—to be associated with anything so mundane as archery.

Eugen Herrigel1

I arrived in Honolulu late in the afternoon. It was August of 1980 and I was 31 years old. I had been planning the trip for a year and a half. Leaving my wife behind, I had recently resigned from my job on the mainland. I had come to Hawaii to study kyudo, the Zen Art of Archery. My destination was Chozen-Ji, a Zen temple located in the Kalihi valley, a ten-minute drive from downtown Honolulu.

I had written ahead to inform Tanouye Roshi2 , the abbot of Chozen-Ji, of the time of my arrival. Usually when students from the mainland come to Hawaii, he makes arrangements to have them met at the airport and brought back to the temple. However, I had explained in my letter that I would be happy to take a cab if it would be more convenient.

After collecting my suitcase in the baggage claim area, I looked around to see if anyone had been sent for me. Unfortunately, I did not know who I should be looking for. Perhaps the person from Chozen-Ji would not be able to recognize me. I started to feel ill at ease. How long should I wait before taking a cab? What if I took one and missed the person who had come to meet me? My anxiety about entering a Zen temple grew. What did this mean? Was this a message of some sort? Zen masters are known to treat their students harshly. Was this part of my training; or was it a sign I was not welcome?

Finally, after about two hours, I hailed a taxi. I gave the driver the address and was relieved when he told me that he had heard of the street the temple is on. He took the highway towards downtown Honolulu, then quickly exited on to Kalihi Street, the street that Chozen-Ji is on. The road began to climb; the higher we went, the narrower it became. The setting now looked more like a tropical rain forest than a major metropolitan area. The driver told me he had never traveled this far into the valley before. We continued to climb. He slowed down, turned right into a driveway, and told me we were there.

"What kind of place is this?" he asked.

"A Zen temple," I replied.

"I've never seen it before," he said, looking intrigued. "I'd like to come back here some time and have a better look at it."

I paid the driver, got out of the cab, and looked around. It was dusk and very still. In front of me were two sets of Japanese-style buildings separated by a large hill. I walked towards the buildings on my left and saw a sign that read, "Visitors Check in at Office." Below was an arrow that was supposed to point the way to the office. Unfortunately, I could not tell which set of buildings it pointed to.

There was still no sign of activity. I decided to check the buildings on my left. I climbed several stairs and stepped on to the verandah that ran along the outside of the building. I noticed a faint smell of incense and advanced forward. Suddenly, Tanouye Roshi came running out of the doorway. "Quiet, we're doing zazen and take your shoes off!" he said (I later saw the sign at the top of the stairs that said "no shoes past this point"). He motioned me to go back to the stairs and said, "We were wondering when you were going to arrive."

"Didn't you get my letter?" I asked.

"I got the letter," he replied. "You gave us the flight number and your arrival time. You forgot to tell us what day." He slowly shook his head from side to side.

I took my shoes off on the stairs and stepped back on to the verandah. Tanouye Roshi then showed me into the kitchen. "Hurry up and change into your training clothes," he said. "Kyudo practice starts in half an hour and you might as well go. I know this is going to be hard for you."

I changed clothes and waited in the kitchen. An older Japanese man with a shaved head and wearing priest's robes walked by on the verandah. Tanouye Roshi spoke to him in Japanese and brought him towards me. "This," said Tanouye Roshi, "is Suhara Osho." I said I was pleased to meet him. Tanouye Roshi translated.

I had been looking forward to this meeting for a year and a half. Suhara Koun Osho is a Zen priest from the Engaku-Ji temple in Kamakura, Japan, and is also a kyudo master. Tanouye Roshi had met him the year before and had invited him to come to Chozen-Ji to help establish a kyudo school there. This was the end of his second visit to Chozen-Ji; he was scheduled to return to Japan in four days. I had timed my trip to meet and train with him in Hawaii. I hoped that this introduction would make it possible to study with him in Japan later in the year. In fact, I had already arranged a job in Japan so that I would be able to support myself while training with him.

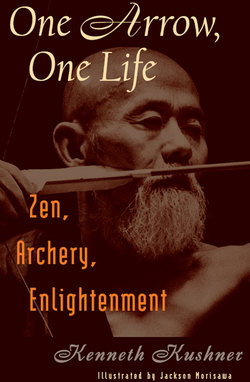

Tanouye Roshi then pointed me in the direction of the kyudo dojo and told me to go there for practice. Disoriented and embarrassed by my entrance to Chozen-Ji, I walked to the kyudo dojo for my first lesson in the Zen art of archery. Over the entrance of the dojo were four Japanese characters. Later I learned that their English translation is "One arrow, one life."

Like most Westerners, until that day what I knew of kyudo came from the book Zen in the Art of Archery by Eugen Herrigel. Herrigel was a German philosophy professor who spent five years in Japan during the 1930s. Wanting to study Zen, he was advised by friends to take up one of the Zen arts. Because of his previous experience with pistol shooting, Herrigel chose kyudo.

I first read Herrigel's book in 1967 as a freshman at the University of Wisconsin. It was the first book that I read in college, assigned by my English composition teacher for reasons I no longer remember. In spite of its popularity, I was disdainful of the book. I had no interest in spiritual matters and was impatient with what I considered to be vague mysticism.

Five years later, as a graduate student in psychology at the University of Michigan, I started studying another Japanese art, karate. I trained hard in it for five years, and receiving a black belt became an important goal for me. Before I could achieve that goal, I obtained my doctorate at the University of Michigan in 1977 and moved to Toledo, Ohio. I continued to prepare for my black belt examination there.

The year before I moved to Toledo, I met Mike Sayama, a fellow graduate student. I learned that he had studied martial arts at a Zen temple named Chozen-Ji in Hawaii. He invited me to practice zazen with him. Still having no interest in Zen and finding unappealing the thought of sitting cross-legged on the floor for long periods of time, I declined his invitation.

Shortly after moving to Toledo, I saw Mike demonstrate a kendo form as practiced at Chozen-Ji. I had never seen such intense concentration before in the martial arts. This was a dimension to the martial arts that was new to me. When he again invited me to train with him, I accepted.

Mike started a small training group for people interested in Zen and the martial arts. I commuted 200 miles a week to participate. Although I joined for the martial arts training, zazen was required of all participants and, reluctantly, I did zazen with them. Through the group, I became interested in Zen for the first time. Ten years after dismissing it as vague mysticism I reread Zen in the Art of Archery and saw it in an entirely new light.

In Zen they say that when you are ready for a teacher, the teacher finds you. In 1977, I was ready. In retrospect I was experiencing a life crisis. For as long as I could remember, my energies were focused on establishing myself professionally. Through four years of college and six years of graduate school, I imagined that when I received my degree my life would fall into place and that I would have no worries. In 1977 I had obtained my PhD, got a good job and began to have articles accepted by professional journals. Yet, for some reason, the fulfillment that I anticipated did not accompany these successes. I was left with a growing sense of uneasiness, a feeling that there must be more to life than professional prestige. For the first time, Zen interested me. I saw Zen training as a way to find the fulfillment that was lacking in my life. Zen became the way out of my existential dilemma.

As I trained in Zen, my attitude towards the martial arts changed. Where once I saw the martial arts as means of self-defense or physical conditioning, I now saw they also afford the opportunity for spiritual growth. Soon, pursuing a black belt became yet another meaningless goal in my life; progress in the search for one's true self cannot be measured by a piece of colored cloth.

The Japanese affix the suffix "do" to the names of the Zen arts. "Do" is an important word in Zen. It is the Japanese translation of the Chinese word, "Tao." It has no direct equivalent in English, perhaps because there is no analogous concept in Western culture. "Do" is usually translated as "Way" and connotes path or road to spiritual awakening. The Zen arts can be referred to as "Ways" and are not limited to the martial arts: kyudo is the Way of the bow; kendo is the Way of the sword; karate-do is the Way of the empty fist; shodo is the Way of writing ("spiritual" calligraphy); and chado is the Way of tea (tea ceremony). Leggett described the Ways as:

fractional expressions of Zen in limited fields such as the fighting arts of sword or spear, literary arts like poetry or calligraphy, and household duties like serving tea, polishing or flower arrangement. These actions become Ways when practice is not done merely for the immediate result but also with a view to purifying, calming and focusing the psycho-physical apparatus, to attain to some degree of Zen realization and express it.3

It was my search for a Way that lead me to Tanouye Roshi and to Chozen-Ji. I was introduced to Tanouye Roshi by Mike Sayama, when the Roshi visited Chicago in 1978. Tanouye Roshi is a Japanese American who was a music teacher until he was certified as a Zen master in 1975. Chozen-Ji and its training center, the International Zen Dojo of Hawaii, were founded in 1972 by his teacher, Omori Sogen Rotaishi, who is direct dharma successor to the Tenryuji line of Rinzai Zen. This tradition emphasizes the integration of zazen with the Asian martial and fine arts. Thus, all students at Chozen-Ji practice zazen and most study a martial and/or a fine art. Tanouye Roshi himself has studied the martial arts for years, with an emphasis on judo and kendo.

Shortly before my second meeting with Tanouye Roshi in 1979 I had injured my knee and had to interrupt my training in karate. My interest in karate was waning anyway, especially as I was exposed to aikido in our training group. Hoping that he would say aikido, I asked Tanouye Roshi what would be the best martial art for me to study. I was surprised when he suggested kyudo. He gave several reasons for this recommendation. First, he thought that it would be easier on my knees than karate. Second, he said that at my age (29) I was too old to gain mastery in karate, aikido, or any of the more physically active martial arts. Finally, he thought that training in kyudo would be a good way to improve my poor posture.

I can think of few other times in my life when a decision felt so correct. In spite of the fact that I had never considered studying kyudo before, I had the sudden sense that studying it was not just the right thing to do but that it was an obvious choice. I thought back to Herrigel's book and it seemed to outline the type of spiritual path that I was looking for. Since kyudo instruction was practically unavailable on the United States mainland, Tanouye Roshi suggested that I come to Chozen-Ji. I immediately started making arrangements to spend a prolonged period there.

Kyudo training had just started at Chozen-Ji. The previous year, Tanouye Roshi accompanied Omori Rotaishi on a cultural exchange to Europe sponsored by the Japanese government. It was on that trip he met Suhara Koun Osho, who was also participating in the cultural exchange. Tanouye Roshi invited him to come to Chozen-Ji to help Jackson Morisawa, one of Tanouye Roshi's students, establish a kyudo school there.

Upon returning from Japan in 1981, I moved to Madison, Wisconsin. I have returned to Chozen-Ji once or twice a year to continue my training with Mr. Morisawa. On my third visit to the temple, in 1983, Tanouye Roshi suggested that I write a book that would help Westerners better to understand kyudo; that is my hope in writing this book.

In spite of the immense popularity of Zen in the Art of Archery, one of the most widely read books on Zen ever published in the West, little is known about kyudo in the West today. While judo and karate are household words, few people would even recognize the Japanese name for the Way of the bow. No doubt this is due to the fact that Herrigel never used the word "kyudo" in his book. Kyudo instruction is still almost unavailable in the United States, in contrast to what must be thousands of schools of other martial arts. Until very recently, Americans interested in kyudo were obliged to travel to Japan for instruction.

My primary focus will be on the relationship between kyudo and Zen. In so doing, I will attempt to expand on the relationship between kyudo and traditional Zen training that was described by Herrigel. The beauty of Zen in the Art of Archery is its brevity and simplicity. Herrigel did not elaborate on many of the philosophical and technical points to which he alluded. My intent is to explain these to the present reader and to put them in the context of Zen training.

My understanding of Zen and kyudo has been shaped by the philosophies of my teachers. In this regard there is one fundamental way in which the philosophy of kyudo training at Chozen-Ji differs from that described by Herrigel. In the Chozen-Ji school of kyudo, the practice of kyudo is integrated with the practice of zazen. At Chozen-Ji, training in the Ways and zazen are complementary processes. Training in kyudo facilitates one's progress in zazen, and one's progress in zazen facilitates one's kyudo.

In this book, I hope to elucidate this complementarity between kyudo and zazen. What I will say about kyudo applies to any Zen art. Most people who study martial arts do not practice zazen. Conversely, most people who train in zazen do not study a Zen art. My hope is that this book will help bridge the gap between Zen training and training in all of the Ways.

This book is not intended as an instruction manual in either kyudo or zazen. The reader should not expect to learn how to practice kyudo or zazen by reading it. Rather, I hope to explain why someone would want to study kyudo; how something as "mundane" as archery can be elevated to a serious spiritual experience when it is studied as a Way. In order to view kyudo as a truly spiritual endeavor, one must treat it as a microcosm of life. In this book I will try to explain how principles involved in the seemingly simple process of shooting an arrow at a target can have profound implications for how one leads one's life.

For readers who may be interested in learning more about the Chozen-Ji traditions of kyudo in particular and of Zen training in general, there are two books that I recommend. First, for those interested in learning more about kyudo, I recommend the book Zen Kyudo by my teacher, Jackson Morisawa.4 It is a comprehensive treatise on the Chozen-Ji school of kyudo. It delves into the technical, philosophical and spiritual aspects of Chozen-Ji kyudo to a far greater extent than I will in this book. It includes detailed explanations and diagrams of the techniques and procedures of kyudo. Readers who are looking for instruction in zazen would be interested in the book Samadhi: Self Development in Zen, Swordsmanship, and Psychotherapy, by Mike Sayama,5 which has translations of instructions by Omori Sogen Rotaishi. Dr. Sayama's book is also of particular interest for anyone interested in learning more about the philosophy and lineage of Zen training at Chozen-Ji. It also elucidates the psychological aspects of Zen and Zen training in much greater depth than I will in this book.