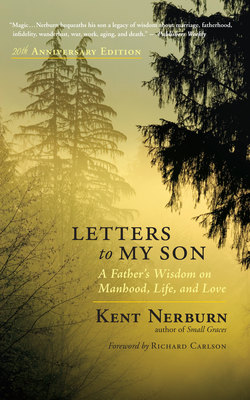

Читать книгу Letters to My Son - Kent Nerburn - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

This is not a book I intended to write. The world is full enough of grand moralizing and private visions. The last thing I ever intended was to risk adding my name to the long list of those involved in such endeavors.

Then, in midlife, everything changed. I was surprised with the birth of a son.

Suddenly, issues that I had wrestled with in the course of my life and questions that I had long since put to rest rose up again in the eyes of my child. I saw before me a person who would have to make his way through the tangle of life by such lights as he could find. It was, and is, incumbent upon me to guide him.

For now this is easy. His life does not extend much beyond his reach. I can take him by the hand and lead him. But before long he will have to set out on his own. Where, then, will he find the hands to guide him?

I look around and I am concerned. The world is a cacophony of contrary visions, viewpoints, and recriminations. Yeats’s ominous warning that the best lack all conviction while the worst are filled with passionate intensity seems to have come to pass. Good men everywhere realize that the world we have made is also the world we have failed, that our brightest dreams and our greatest fears lurk just over the horizon. Acutely aware of both, we stand mute, driven by our hopes, silenced by our doubts.

I can no longer afford this silence. I want my son to be a man of good heart who reaches out to the world around him with an open mind and a gentle touch. I want him to be a man of belief, but not a man of judgment. I want him to have explored his own moral landscape so that he will not unwittingly do harm to himself or others. To be such a man he needs to hear voices that speak with empathy, compassion, and realism about the issues of becoming a man.

And so I take my place among those attempting to provide such a voice.

I bring to the task such skills as I have: a love of the language; a belief in the higher visions of the human species; a complex mélange of anger, wonder, and despair at the world in which we live; years of learning, miles of travel, a love for the wisdom of all spiritual traditions, and a faith in the inexhaustible miracle of the experience of life all around us.

But above all, I bring this:

One day last week a former student of mine methodically drove his car to the end of a street, pushed the accelerator to the floor, and catapulted himself off a cliff into a lake far below. On the same day I listened to a man speaking about his journey to India to study with a woman who could read his spirit by laying her hands on the sides of his head and staring into his eyes. That evening I found myself sitting with an old drunken man on a bench outside a store talking about the pleasures of catfish.

It is my gift to be able to embrace all these people and all their truths without placing one above the other. I can enter into their beliefs and give assent to each of them and learn from each of them. And I can pass their truths along.

This may not seem like much. But I value it above all else. The lonely old neighbor with her thirty-six cats, the shining young man at the door with his handful of religious literature, the good teacher, the honest preacher, the junkie, the mother, the bum in the park who told me never to take a job where I had to wear the top button of my collar buttoned and not to mess up my life like he did — I can hear all their truths and I can celebrate them.

If I can take these simple truths and elevate them beyond the anecdotal, I can offer something of value to my son and to other fathers’ sons. I can offer a vision of manhood that is both aware of our human condition and alive to our human potential. I can offer the distilled insights of the dreamers and the doubters, the common and the rare. And in the process, perhaps I can reveal something about manhood to those readers, both male and female, who seek a compassionate place from which to survey the vast and confusing landscape before us.

— Kent Nerburn

Bemidji, Minnesota, 1992