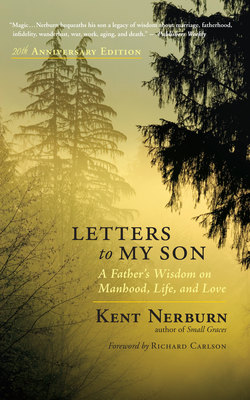

Читать книгу Letters to My Son - Kent Nerburn - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

STRENGTH

The other day I saw a group of boys pushing against another boy outside a local store. The lone boy was gesturing as if he was going to hit back at his attackers, but you could see he was afraid. The others kept crowding him and taunting him and daring him to strike them. Then they were going to jump on him and beat him. They only needed that first blow to set them loose.

Finally, an older man walked by and stopped them. The taunters looked at him and skulked away. The lone boy was free, but not safe. His attackers will be waiting for him on another day, in another place.

I don’t know what caused this confrontation. I’m sure it was nothing important. The wrong word, the wrong action. But from it came a ritual as old as time — boys measuring themselves by their physical strength.

It’s a sad ritual, and not one to make us proud. Yet, somehow, this notion of physical strength has survived in our biological coding as something significant, and even the best of us feel its shudder deep inside us. It is a residue of our days as hunters and protectors, when our physical prowess was a legitimate measure of our success as men.

Now it is a caricature of all that we need to be.

For ages we have lived with this biological imperative by which manhood has been defined as strength — strength to master others, strength to master our emotions, strength to master the world around us.

Can we lift more, carry more, run faster, work longer than others? Then we are better men.

Can we subdue another person physically? Then we are stronger men.

Can we resist tears when we experience joy or sadness? Then we are truly men of strength.

The world doesn’t need this version of strength anymore. We are not locked in some physics of survival where we must turn force against counterforce in an elemental battle to see who will prevail. We need greatness of spirit more than we need greatness of physical strength.

Let me tell you two simple stories. Perhaps you will see what I mean.

Last week I was home alone. I had two tickets to a chamber orchestra concert to be held on Friday night.

I started calling our friends. Those who might enjoy the concert were busy. Those who might be willing to go didn’t really like classical music.

The ticket hadn’t cost much — I could have just thrown it away and gone alone. But something kept gnawing at me.

For most of the morning I avoided the issue. I tried to ignore the ticket that sat innocently in my billfold. By noon it weighed about a thousand pounds.

Finally, I got in the car and went over to the local nursing home. I went to the nurses’ station on the second floor and found the head nurse. “Is there some resident here who can walk a bit, likes music, and wouldn’t mind going to a concert with a stranger?” I asked.

The nurses who were standing nearby looked at each other and began discussing various residents. “Edna? Florence? Joe?” After a few minutes they decided that Edna would be the perfect choice. We went to the dining room and asked her. “No, I don’t want to,” she said. She was afraid.

So we decided on Florence.

We went to her room. She was sitting in her wheelchair with her hands in her lap. She was probably eighty, almost completely blind, and had heavy orthopedic shoes with straps and four-inch soles and laces up the side.

“This young man has tickets to a concert tonight, Florence,” the nurse began. “He wants to know if you’d like to go.”

I laughed at the nurse’s phrasing. “A nursing home is the only place left where I’m likely to be called a young man,” I said.

Florence turned her heavy glasses toward me. “Sure,” she said. “Let’s go. I haven’t had a date for a while.”

We talked a bit about the concert and the difficulty she might have getting in and out of my car. We set a time when I would pick her up, and I went off about my daily business.

At seven-thirty I arrived back at the nursing home. Florence was dressed and sitting in her wheelchair in the dark. She had on green cotton gloves and was clutching a purse. I said hello to the nurses and off we went.

Everything went smoothly. Florence was able to get into my car. The wheelchair fit into the trunk, if just barely. The people in charge of the concert helped me get Florence into the auditorium and stayed with her while I found a place to park.

Florence decided to stay in her wheelchair during the concert; I had an aisle seat and could stay next to her. Until the lights went down, we talked about people and places we both had in common. While the orchestra was tuning up I read her the concert program — Vivaldi, Bach, Dvorák, and Beethoven.

Then the music began. For an hour and a half Florence sat silently, staring with empty eyes toward a stage she couldn’t see and listening to music that she had not heard in years. There was a tiny smile on her lips. She never took off her gloves or let go of her purse.

At the end of the concert, after the applause had died down, she asked if I would get her a copy of the program. “I can’t read it,” she said. “But I’d like to have one anyway.”

There’s not much more to the story. I took her home. She thanked me. The nurses joked with her and wheeled her down the darkened hall. Her green gloves were resting on her purse, and under her purse, flat on her lap, was the program.

That’s all. Nothing more.

Now, the second story.

One summer when I was just out of high school I worked at a country club with a man named Haines and his son, Calbert. Haines was about sixty and always had a gentle smile on his face. Calbert was in his midtwenties and wore a slicked-up pompadour and tinted glasses. Because they were black they were required to eat downstairs near the boiler room rather than in the employee lunch area upstairs near the kitchen. I used to bring my food down to eat with them.

“You don’t have to do this,” Haines would say. “You’re not proving nothing.”

“I’ve got to do it because I don’t think what they are doing is right,” I responded.

“Suit yourself,” Haines would say. “Can’t do you no harm.”

Calbert would just smile and shake his head. “You’re just messing yourself up over nothing,” he would say as he pulled out the cribbage board. “Nothing you can do about it.”

Day by day I would watch Haines and Calbert. I complained to the manager and complained to the other staff. Nothing was changed. Yet, never did I see Haines or Calbert show even the slightest hint of rancor or anger. They just ate their lunch, played cribbage, and went back to work cleaning the men’s locker room and shining shoes.

At the end of each day they were given a list of shoes that were to be shined and ready to go the next morning. Sometimes when I would go home Haines and Calbert would still be there shining shoes while the laughter of golfers and their families filtered down from the dining room and lounge upstairs.

At the end of the summer I went off to college, but I continued to visit Haines and Calbert when my travels took me past the country club.

One day I came across an article in our local newspaper. There had been an attempted burglary at a nearby country club — not the one where Haines and Calbert worked, but another one where I had caddied when I was younger. A black man had been shot and killed after breaking into the locker room with the help of a friend who worked there.

The black man was Calbert.

The policeman who had shot him was a man who had been several years ahead of me in high school. He had been a thug even then; everyone had feared him because he beat up people with chains and tire irons. According to the article, he had claimed that he shot in self-defense, though the bullet had entered through Calbert’s back and Calbert had not been carrying a gun. Because there were no witnesses, no case was being filed against the officer.

I was wild-eyed with anger and grief. I went over to see Haines. I found him at his bench shining shoes. “Calbert wouldn’t try to kill anybody,” I said.

“I know that,” Haines answered, putting new laces in a white leather oxford.

“I went to school with that cop,” I continued. “He was a thug then and he’s a thug now. He just shot Calbert in the back.”

“I know that,” Haines responded.

“Well, aren’t you going to do anything?” I yelled.

Haines looked directly at me. His eyes were clear and sad. “Calbert shouldn’t have been there,” he said. That was all.

With all the pain he had known in his life, with all the injustice and unfairness that had surrounded Calbert right up to the moment of his last breath, Haines refused to place blame elsewhere. Calbert shouldn’t have been there.

I raged and fumed and choked back tears. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. A man had lost his son in an unjustified shooting by a thug in a uniform, and the justice system was turning a blind eye. How could a person be so passive in the face of such unfairness?

Haines just smiled at me and shook his head. “You’re angry. I know. I’m angry, too,” he said. “That man killed my son. I want to see him behind bars and I’m going to try to put him there. But that don’t change nothing Calbert did. Calbert got shot because he was somewhere he didn’t belong. Nothing I do is going to make what he did right. He shouldn’t have been there.”

I stood dumbstruck before this man who had just lost his son. He was obviously filled with pain, but his sense of calm was profound. He did not mount arguments to justify his anger or a hope of revenge. He did not take rash action that would increase the cycle of suffering. He stood in his strength, contained in his grief, secure in the sense of honor with which he lived his life.

In some men this would have seemed like passivity. But one look into the wisdom in Haines’s eyes was enough to tell me that this was not a man refusing to act out of fatalism or cowardice. He knew where the moral center of his being was, and he was as strong as a mountain.

I could not have been that strong. I would have flown into a rage and set out to exact some horrible vengeance on Calbert’s killer. To outsiders I might have looked like a torrent of righteousness and a tower of strength. But I would not have been as strong as Haines.

Haines, on the other hand, would never have been strong enough to go to that nursing home to ask a stranger to a concert. He accepted the harshness of life and it was not his way to reach out to create happiness for others. He would have let the ticket go unused. He might have congratulated me for my act. But he never would have done it himself. It was not part of his strength.

Two men. Two moments noticed by almost no one. Two very different ways of being strong.

This is important for you to know. Every man has a different strength. A man who chooses to live at home with aged parents, or a man who devotes himself to endless hours of labor to learn the violin or the secrets of quantum physics has a quiet strength that few will ever know. A man who masters his own desire for independence and gives himself over to being a kind and loving father is strong in a way many others could not match, but his strength is never seen.

You need to find your own strength. We have an instinctive tendency to make that false association of strength with force, and to measure it by moments of high drama or grand flourish. We are easily able to see strength when a man climbs a mountain or wards off an intruder. We are drawn to him because he overcame fear, and that is something we readily understand.

But there is much more to strength than overcoming fear. All men are afraid of something. Some fear being hurt in a fight; some fear not having a woman; some fear being embarrassed in front of other people; some fear being alone. Focusing your manhood on your fears and defining your strength by the fears you overcome does not make you strong. It only makes you less weak. True strength lives where fear cannot gain a foothold because it lives at the center of belief.

Martin Luther may have put it most succinctly when he stood up for his vision of God. “Here I stand,” he said. “I cannot do otherwise.” When you can make this statement about something, all else falls away. You find that your fear is overcome by your belief, your anger overcome by your conviction. Like Haines, you stand in a place of immense peace that cannot be moved, and you possess a strength that is beyond manipulating, beyond arguing, beyond questioning.

Try to find this strength in yourself. It lies far below anger and righteousness and any impulse toward physical domination. It lies in a place where your heart is at peace.

Can you turn and walk from a fight when all those around you are jeering at you and telling you you’re afraid? Can you befriend the person nobody likes even though you will be mocked for your kindness? Can you stand up to a group of people who are teasing a person who wants nothing more than to be part of that group? These are the daily tests of a young man’s strength.

Can you stay away from a friend’s girlfriend even though you want her? Can you turn down a drink or a joint if you don’t want one? Can you do these things with kindness and clarity rather than with self-righteousness?

If you can, then you are strong, far stronger than those who can defeat you physically. Remember, strength is not force. It is an attribute of the heart. Its opposite is not weakness and fear, but confusion, lack of clarity, and lack of sound intention. If you are able to discern the path with heart and follow it even when at the moment it seems wrong, then and only then are you strong.

Remember the words of the Tao te Ching: “The only true strength is a strength that people do not fear.”

Strength based in force is a strength people fear.

Strength based in love is a strength people crave.