Читать книгу Cassandra - Kerry Greenwood - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

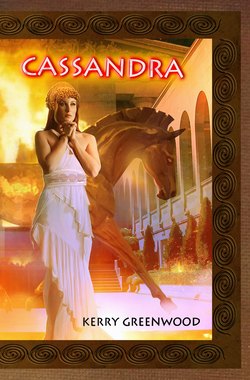

III Cassandra

ОглавлениеI was not supposed to see the mystery called childbirth until I had become one of the Mother's maidens with my first bleeding of sacrifice blood. But I teased my teacher Tithone so incessantly that she set me fifteen pectoral herbs to learn perfectly and said that after I had managed a broken bone all by myself, I could come to watch Clea give birth. She was expected to do so very soon.

I was twelve and convinced I knew everything.

I spent a week annoying my twin by insisting on haunting the exercise field, where the young men practised fighting and the maidens shot their bows. Eleni only stopped complaining when Hector gave him spear-throwing lessons along with Polites, our brother, who was four years older. This was an honour and Eleni stripped and took to the field with as much pride as any Trojan warrior. I giggled at the contrast between slim fifteen-year-old Polites, with his long oiled thighs under the war skirt, Hector as tall as a tree and little Eleni with his stumpy ungrown shape. However, I did it privately and behind my hand.

I was waiting for someone to hurt themselves. Childbirth is the great female mystery and I was eager to see it. I was not a nice child.

I sat watching the warriors, instructed by Hector, practising with the spear. Our Trojan spear is shorter than the common, but heavier, with a barbed bronze head. It is used for stabbing at close quarters and can be thrown a long distance with a spear thrower, a longish piece of wood with a crook at the end. This is a Trojan skill and takes learning, but it can cast a spear three times the distance that an unassisted man can throw it.

I wriggled into a more comfortable seat with my back against the sun-warmed wall of the temple of Apollo, the sun god aspect of the Lord Dionysius. He rules prophecy, so he was my god. I felt very comfortable in his temple but was always on the brink of falling asleep when there, and I wanted to watch. I pinched my wrist and sat up straighter.

The maidens, a flutter of coloured tunics, were further away, near the little hill, between the city and the river Scamander. I could see a purple tunic among the pale green, ochre and rose. It was probably Andromache, our playmate and destined wife of our brother Hector. She resembled Eleni and me, being pale skinned with dark golden hair and the grey eyes which marked the god-touched, although she had not shown any sign of prophecy or skill in healing. In fact, she had no interest in healing but was good at arms. The elders thought that she might be protected by War, him whom the Argives call `Ares'. The Amazon Myrine, who was of course War's child, trained Andromache especially hard, stating that she of all the maidens would need to know how to fight.

Even at ten Andromache was tall and strong. I could hear Myrine shouting at her to keep her wrist tensed against the pluck of the string, and scolding her for allowing it to skin her inner arm. Andromache drew and loosed again. She would not cry. Andromache never cried.

Then I heard a cry and a thud. Instantly I was up and running for the centre of the field, where two young men had been wrestling.

I ducked past Eleni, who was leaning on his spear, circumnavigated Hector and slid to a halt next to the fallen, whom I recognised as Sirianthis. He was a hapless boy, always hurting himself. I could have guessed that my first broken bone would be Siri. His mother put it down to her having spent most of her pregnancy tripping over things. He was a pleasant boy, though, and everyone liked him. He tried very hard and never minded the other boys laughing at him.

He was lying on the ground, curled around his injury, clutching his upper arm and trying not to cry. I recognised the strange fish hook shape of his body on the dusty ground and said, `Siri, I need a broken bone. All you've done is dislocated your arm.'

`Sorry,' he panted. `It hurts. Can you fix it, Cassandra?'

`Of course, but if you had to hurt yourself couldn't you have broken something? I don't know if Tithone will think that this counts. I'll get Hector. It will be all right in a moment, Siri, I promise. Who are you?' I asked the other boy.

He turned a shocked face up to me and said, `Maeron, lady. I didn't mean to hurt him.'

I ignored this. `Go and get your tunic, lie him on his back with the tunic rolled up between his shoulder blades while I fetch my brother.'

Hector, who was about to cast the spear, put it down again and followed me to where Siri lay whimpering. The stretched-out position strained all his displaced sinews, those strings which knit a muscle together. Hector leaned down and stroked the hair from the boy's sweating face.

`It will stop hurting soon, little brother,' he said soothingly. `Maeron, sit beside him and hold him still while I pull. No, grab the other shoulder and brace yourself.'

`Hector, Hector, let me,' I begged, hauling on his elbow. `Thithone said I had to do this before I can see the mystery.'

Hector looked at me sternly. `A warrior must not be left unattended because of the healer's private purposes,' he said. `But you may give me orders, Cassandra, if you do so right away.'

When my brother called me Cassandra like that he was seriously displeased and I quaked. But I knew the procedure and ordered, `Take his wrist in your hand, brother, and put your foot under his arm pit. Now pull gently until the arm goes back into the socket.'

I had seen this several times. It was always fascinating. As Hector pulled on the arm, the shoulder joint moved under my hand, from an ugly displaced lump to the shape of the boy's proper shoulder. All medicine, said Tithone, was restoring the body to its proper shape and condition. There was a click, Siri bit back a cry, and Hector laid the restored arm across the boy's chest.

Hector looked at me. I remembered what remained to be done.

`Wriggle your fingers, Siri,' I ordered. `Can you feel your hand?'

`Yes, Princess. Thank you.' Maeron was holding Siri close and I perceived that they were lovers. I blushed to think that I had just ordered poor Maeron about, as though he was a dog, when he must have been worried about Siri. And Hector was angry with me. This healing was more difficult than it looked. It involved people; mere knowledge of methods of healing did not begin to cover it.

`Now, Cassandra, what next?' asked Hector. Luckily, I knew.

`I bandage his arm to his side and send him off the field to rest, taking broth and marshleaf infusion to soothe the inflammation, and he is not to move his shoulder for three days. I can apply oil of mint to cool the joint and reduce the swelling and he must be watched for fever,' I parroted, making a bandage from Maeron's tunic. Hector bent his head in approval I watched Maeron help his friend to his feet and they limped off the field, passing into the city through the Scamander Gate, which was nearest to Siri's house.

`Now, Cassandra, we must talk. Or rather, you will talk to me while Eleni goes with Polites to practise the use of the spear thrower.'

`Eleni went, glancing back at me in compassion. Hector was very seldom angry with us but when he was he did not rage or slap. Rather he was sad and measured and his every word sank into the heart and stung like a thorn.

`Oh, Hector, I am so sorry...' I began.

Instead of hugging me, he asked gravely, `Why are you sorry?'

`I shouldn't have thought of Siri as a task I had to do in order to see childbirth. I'm fond of Siri, but I treated him like a thing.'

`You want to be a healer, don't you?'

`Yes.'

`Then you must know that all your patients are people, and you have to love them. Not all the time, Cassandra, and not for ever. But while they are in your care then they must have your whole heart. Otherwise you will never heal them.'

`But Hector...' I ventured closer to him and took his hand, `that can't be right.'

`Why not?' he was relenting enough to argue and I felt instantly better. We began to walk back towards the city of Troy. The walls shone white in the morning, the walls, the height of three men, built by Heracles the hero in recompense for his massacre of my grandfather and his sons.

`The best healer of these sorts of injuries is Myrine the Amazon,' I stated.

`Yes,' Hector agreed.

`But Myrine is rough,' I protested. `She grabs and heaves and swears at them, curses them for foolish men, closes wounds with her fingers, pressing hard enough to make them cry out, and then she curses them again for weaklings and children.'

`She tended me when I fought that boar,' said Hector. `Her harsh words recalled my courage and her hands were skilled and strong.' I saw the scar down the outside of his thigh where the tusks had sliced his flesh. `She sucked out the dirt and poisonous saliva with her own mouth, swearing by Hecate that I was the clumsiest hunter she had ever met. Can you doubt that she loved me then?'

I thought about this, reviewing what I had seen of Myrine the Amazon. It seemed unlikely but it was true. She did love her patients. I nodded.

`Go then, little vulture,' said Hector, patting me. `Tell Tithone you have replaced a dislocated shoulder and beg her, from me, to consider this equivalent to the task she set you.'

To salve my conscience, I went first to the small house in the first circle where Siri lived. His mother greeted me and gave me a small clay bird as a present for tending her accident-prone son, and I went off to find Tithone in a very guilty state.

I told her what had happened and she listened without a word. Then of all things, she laughed, a bright and joyous laugh, almost like a girl's. It came strangely from Tithone's aged face, and I was disconcerted.

`Aren't you angry with me, Lady?' I asked. She hugged me to her bony bosom.

`Ah, little daughter, more years away than you can count I did the same thing, and my brother called me a vulture too. You will be a fine healer, Cassandra, if you keep the great warrior's advice in mind. You may not like your patients, or approve of them, or let them become close to you. But while they are yours, you must love them. Hmm. Your lord brother is a fine man, a fine man. Troy is fortunate in its captain. How was Siri?'

She just assumed that I had been to see him. She was always right, Tithone my teacher. I liked her anyway.

`He is a little feverish. I gave him poppy broth and his mother has oil of mint for the swelling. I will go and see him tomorrow.'

`I'll send someone tonight. The condition of the young changes faster than with adults. They heal faster, but they also deteriorate faster and they die quicker. Remember that.'

`Yes, Lady.'

`Recite the pectoral herbs,' she said, and I brightened. This meant that she had accepted Siris's dislocation as my broken bone.

`Coltsfoot, mint, squillis, marshleaf, red poppy, thyme, vervain, comfrey, yarrow, sundew, ivy, hyssop, lungleaf, blackthorn bar, elecampagne,' I announced.

`How are they used?'

`For a cough in the chest which bubbles, Lady, an infusion of elecampagne, coltsfoot, lungleaf and thyme but not poppy.'

`Why not?'

`It stops a cough, Lady, so that the person can't spit out the fluid.'

`Good. For a dry cough?'

`Lady, honey and red poppy, marshleaf and sundew.'

`Good. Why do you use thyme?'

`Lady, it cools a fever and makes the lungleaf work better.'

`Good. Does marshleaf affect the cough?'

`No, Lady, it just soothes the insides.'

`Good. Now, Cassandra, tell Nyssa that you will be away for a while, collect your mantle, and meet me at Clea's house.'

I did not wait to thank her, but ran out of her house into the steep street. Eleni had returned from the field and was ready to console me, but I was alight with purpose and threw myself into his arms, laughing.

`You recover fast,' he said suspiciously. `Wasn't Hector angry? Ouch! Take care, twin!'

`Eleni, are you hurt?' I drew away and felt him over anxiously.

There were hot spots in his muscles, discerned with my fingers, but he did not seem to have broken anything.

`It's nothing,' he said grandly. `Hector says that all warriors have sore muscles after exercise.'

I clipped his ears affectionately and gathered up my mantle, the warmest one for winter. `Tithone's taking me to see Clea give birth,' I said to Nyssa. `She said to tell you I'd be missing for a while.'

Nyssa did not share my excitement. She kissed me sadly and when she drew away I saw that she was crying.

`Oh, Nyssa!' I said, conscience struck. `I won't be long. I promise.'

`It's not that, Princess. You are growing up. Soon you will leave me.'

`Never,' objected Eleni, hugging her from the left side as I embraced her from the right. `We'll never leave you!'

When I left he was comforting Nyssa by loudly and childishly demanding instant attention, a bath and massage for his battle fatigue. I love my twin very much.

Clea was seventeen. This was, Tithone had previously informed me, her first child. Her husband was a tall, strong Trojan and she was a delicate-boned Phrygian woman, so time and care would be needed to deliver her safely.

Naturally, I was familiar with the methods by which women receive the seed of men which grows in the womb. When I came to leave the maidens, I would sit as every other woman in the city had to sit, with a band of plaited horse-hair around my head in the Place of Maidens. There I would stay until a stranger dropped a golden token of the Mother into my lap and took my hand, saying, `In the name of Gaia'. Because I was a princess of the royal house, no arrangements with suitable boys could be made. I would have to lie down with a complete stranger, preferably a visitor to the city. We knew that the Maiden would infallibly be angry with the man who took one of the handmaids away. She would be even angrier with one who stole a princess. Therefore the foreigner. The lovers were always masked with the face of Dionysius, Lord of the Trojans. One such man would lead me away and by means of his phallus I would leave my allegiance to the Maiden and join my fate to the Mother.

I could not wait. The kisses and stroking hands of my fellow maidens were sweet, but they did not satisfy me. Some of them would never leave the Maiden; they had no wish to encounter the phallus of the Lord. Myrine the Amazon was one of these. Until I left the maidens I could not marry my brother and twin Eleni, my dearest love. Time moved too slowly for me.

Cleas was sitting, bent double, clutching her belly and moaning. Tithone came into the small house in the second circle and announced briskly, `The blessing of the Mother upon this place.' Then she proceeded to order Clea's neighbours to sweep her house clean while we moved Clea into the street to strip and wash her over the earthenware trap in the drain. The smaller houses in the circle did not have elaborate plumbing, as the palace and the large houses further up did. Still, they all had water piped from the triple spring which flowed at the very highest point in the city and they all had a privy which opened into the main sewer and was flushed with water - Priam had ordered all who built houses to see that this was so. Cities in such godless places as Achaea, Tithone said, had not discovered that filth and excrement breeds plagues in the miasma that surrounds them, polluting the air and poisoning the people, bringing swift vengeance from the god Apollo, who loathes such irreligious behaviour.

Troy never had a plague.

Clea's belly, which had ridden high, seemed to have changed shape. As we washed her with salty water and then with fresh infusions of hyssop, her neighbours cleaned her house, untying every knotted cord. We smoothed back Clea's hair and doused her three times with cool water to which soapleaf had been added. Passers-by touched her reverently on the belly. Touching a woman so close to the female mystery is supposed to bring good luck.

After that we led her back inside her house. Tithone began the incantations of the goddess, a long, long chant which I knew very imperfectly. As acolyte, I wrapped Clea in a red chiton and combed her long hair so that never a tangle remained.

I knew that Clea's husband was in the temple of the Mother and would remain there, dedicated to prayer, while Clea was in labour. If she lived, he would be garlanded by the priests and sent down the hill from the temple with rejoicing. If she died, he would remain there in mourning for a moon from waning to waning, eating only barley bread and speaking to no one. Unless he did this, he could never marry again.

If the baby died, the temple would take both of them for the same period, expiating the Mother's wrath and despair at the loss of her child.

I began to wonder if I really wanted to attend childbirth, but there was no turning back. The chant had begun, the woman was in labour, and I was acolyte and forbidden to look away, leave or be sick.

Tithone paused between cantos of the chant and began to talk to Clea. She was sweating and in pain. I had not realised that childbirth was painful. I thought it was a joy to bring a new creature into the world. Now I saw Clea was crying and her clutch on my hand was desperate. Tithone laid a hand on her belly, and asked gently, `How long since the brine came, Clea?'

`It was the time of the hottest sun,' gasped Clea. `I hurt!'

`Ah,' said Tithone. It was two watches since then - almost half a day. It seemed a long time to me. `The child in the womb lies in brine like sea water, Cassandra,' she said to me. `When it is ready to be born the sea water drains away, and the child struggles to break free. Lay your hand, here.'

I did so, and felt a strange pulsing under the drum-tight skin.

`A live thing wants to be free and reach the light,' said Tithone, `but it will take its time. What I must do, daughter, is continue to chant and you must massage her back, here and here' - Tithone always knew where it hurt - `and talk to her.'

`I hurt!' gasped Clea again. I laid both palms to the place indicated by my teacher and felt Clea's pain. It struck through my vitals and I gasped.

I had such a bond with Eleni. If he hurt, so did I - that is how I had known that his battle bruises were not serious. This was different. It was as though the Mother had decided to let me know how childbirth felt, though my own body was as yet unripe. My own unformed breast ached. My untouched womb contracted like a fist. I slid down until I was embracing the labouring woman as she sat on a backless chair, my face between her shoulder blades, my belly against her back. The muscles were as hard as rock under my fingers.

Tithone had been watching me; I think she knew that this might happen. She did not break off the chant, but touched me briefly on the head as though she was blessing me.

A creature was struggling to be born: a live thing, with consciousness of a vague sort, but with appallingly fierce drive and will. It did not care if it tore its mother apart in the birth; all its force was set on breaking free of the confining prison of the womb and I had to help it. Unconsciously, I embraced Clea closer, and began to breathe in her rhythm. Our hearts beat as one. When she groaned, so did I. When a contraction ripped her, it tore me also. Under my hands with the god-sight, I saw the little animal twist and claw with hands that had all their nails.

For the first watch it was only pain. I found later that Eleni in Nyssa's arms writhed in agony and nearly frightened her to death until she sent to Tithone and found out what I was doing. Thereafter she told Eleni that this was what his mother had borne to birth him, which subdued him for days.

Pain, after a while, transcends hurt. Clea was washed with waves, which I translated, once I had the trick of it, into force and pressure. It was not the same pain as a burn or a broken bone, which hurts differently, treated or untreated. This was more like an internal qualm which signifies that one has eaten too many unripe berries and the body is trying to be rid of the poison. Yet it was not that, for the woman was bearing the pain gladly, in order to be lighter of her burden and to bring alive to the goddess a new person.

At the point when I thought I might die of this pain, I looked imploringly at my teacher. She did not pause in her chant, but made a gesture which seemed to gather something up into a ball. I groaned through another contraction until I realised what she meant.

It was all one, birth and death and life. At that realisation I got the trick of translating pain into pressure and I got my mind back, so that I could consider what I was doing.

Troy is ruled by the tides. They dictate when Hector's ships can leave and when they can come in. They wash the beaches clean and bring fish and wrecks to our shores. The moon is mistress of the tides. They wax and wane as she becomes the maiden, mother and crone, vanishing to renew herself in the dark time we call the Night of Hunted Things. This birth was tidal: each new wave washed us further up as the sea-creature wriggled to be free and Clea strove to make her body into something from which it could escape.

Wash and crash, I conjured tides. I could hear the chant, though Tithone sounded very tired now. I called up the moon-dragged waters, salt and relentless, and felt the baby writhe under my hands. Clea cried out - it was then that I noticed she had been silent for a long time - and Tithone knelt between her legs.

With a wriggle and a flash and a cry of triumph from Clea and from me, the baby was born into Tithone's hands. There was an instant intoxicating sense of lightness and freedom, which could have come from either Clea or from the baby. I relinquished Clea into her neighbour's embrace and knelt next to my teacher. So small a thing, so perfect, smeared with blood and grease and opening its mouth to scream.

Tithone laid the baby in a dish full of warm salt water, still attached to its mother by a cord of marvellous complexity the colour of lapis lazuli and coral. No Egyptian worker could have made a twisted enamel so beautiful.

We lifted her and laid her on her own bed, the red cloth swathing her hips tightly. Tithone took her flint knife and a skein of white thread. She tied the cord and cut it, washing the baby clean of blood and grease. Clea panted and was delivered of a pad of flesh, then sagged back into her attendant's arms.

It was a girl child, a fact which would add to the rejoicing.

It was well known that the women of Troy, well skilled and strong, were sought in marriage by many men of the west kingdoms and commanded respect. I marvelled at the small hand which clutched my finger. The newborn opened dark blue eyes. She looked at me coolly, a creature well pleased with the outcome of its struggle, a warrior resting from battle.

Tithone took the baby up and carried her over to Clea, who lay exhausted, battered, and bruised. Blood was still seeping from her loins. She bared a breast for the baby and winced, then laughed, as the hungry mouth clamped shut.

`Go,' Tithone ordered the boy who had been sitting outside the door for the whole day and the whole night. `Tell the Mother that there is a new girl child in Troy and tell Clea's man that both of them are well.'

The boy, who was apprenticed to the priest of Dionysius, sprang to his feet and ran. I heard his hard bare feet striking the cobbles. It was almost dawn. My knees were sore and I was as stiff as a plank, but I was intoxicated with joy. Tithone joined me at the doorway as the sun began to rise in splendour and a cool wind sprang up. The sky was a sea of gold and rose.

`That is the mystery of birth, little daughter,' she croaked, laying a hard hand on my shoulder. `Are you glad to have it?'

`It is a terrible mystery,' I heard myself saying, `but yes, teacher. I am glad.'

Behind us, in the house, Clea's baby began to cry. I felt a jolt in my womb and put down a hand to investigate it. I brought back a palm marked with blood. I had joined the Maidens.