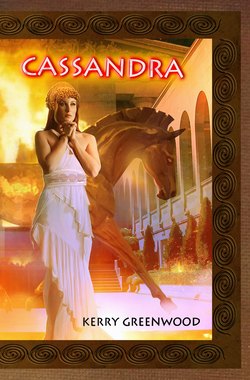

Читать книгу Cassandra - Kerry Greenwood - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

V Cassandra

ОглавлениеNyssa was right. I was growing up.

Ordinarily, I would have moved from my Nyssa's house to the Temple of the Maidens, where the Trojan women were taught rituals, songs, herbs and skills which they might not have learned from their own mothers. This includes spinning, carding, weaving, dyeing, embroidery - we are famous for the beauty of our textiles - and some house-making, metal smithing and tiling. After a few years in the temple, the maidens specialise in whatever it is that they are best at. We are the well-skilled maidens, we Trojan women, and men come to marry us from all over the world, even the Achaeans who dislike our customs and say we are too free. Men come seeking Trojan wives from as far as the Black Mountains on the borders of Caria, where the language is utterly strange.

Those who have no skills are still valued, because we are also, they say, the most beautiful women in the world.

Some, of course, never marry. They stay with the maidens to teach or carry on their own trade or become priestesses of the Maiden. A few go every year from Troy to wander with the Amazons, the women who fight like men. Our friend Andromache would have gone with them if she had not been promised to Hector.

The fate of the women of the royal house is stricter than that of the common people. We must marry where we are given, if there is a political reason. No other women in Troy are so constrained. Others can make their own marriage agreement with their new husband. The daughters of Priam must go where we are sent. Our reward is peace for the city of Troy and for that we would do anything.

Still, it has its advantages. Because I was a princess, and also a royal twin, I was allowed to stay with my brother Eleni and Nyssa our nurse for longer than the others.

At night, in our common bed, Eleni and I discovered new things about ourselves. I was growing breasts. Eleni, in the course of a year after I had seen Clea's child born, had grown tall and slim, and there were other developments, with which we played and gave each other pleasure.

I remember the surprise I got when after handling the papyrus-root phallus, it spurted seed. It smelt of wormwood. I was afraid I had hurt Eleni, but his skin was flushed and he gasped with pleasure. I reached the same delight when Eleni's exploring fingers happened upon the thing which the Trojans call the goddess' pearl. The pleasure was so strong that I felt that my bones had been filled with honey.

Sweet Eleni, sweet twin, so close to me that we were one flesh. But never one flesh in truth. We knew that I was still a maiden and must remain so until the sacrifice to Gaia, otherwise the goddess would curse both of us. Our seed would wither, our bones ache, our sight dim, and the children of such an unholy union would fail in the womb and die untimely. We knew that if Eleni made full union with any woman before he had cut his hair for the father Dionysius and made the sacrifice of wine and honey in his temple he would sprout disfiguring seed and no one would marry him. We ended our nights locked in each other's arms, flushed and sticky but still technically virgins.

Oh my own Eleni. His face on our pillow in the morning light was so young, unlined and pure, his hair lapping my shoulder, his mouth open against my breast. I was twelve before I found out that I could not marry him.

Nyssa told me. We were sorting wheat seeds, a peaceful occupation, sitting in the shade under the vine. The vine leaves made patterns on the marble floor, dark green outlined in gold. We were discarding the dried, darkened or broken seeds and spilling the good plump ones through our fingers to winnow out the bits of leaf. I remember how it poured with a rustle into the basket at our feet.

`You will become a healer, little Cassandra,' Nyssa cooed. `You have a quick eye.'

She could sieve seed faster than me; her eye for imperfections was as bright as an eagle's for prey.

`I think so,' I agreed sleepily.

`You know that you cannot marry your brother, Cassandra,' she said quietly.

It took a moment for the implications to sink in, then I sat up straight and grasped at the sliding tray.

`I can't? Nyssa, I have always meant to marry Eleni! He wants to marry me!'

`Yes, my pet, my lamb, but he can't.'

`They do in Egypt,' I objected. `In Egypt brothers always marry sisters. The word for lover is sister. Aegyptus the sea captain told me.'

`That is Egypt,' she said, taking the tray out of my shaking hands. `This is Troy. You are Priam's daughter, and you must marry where he directs. You cannot marry your brother. You may be given to anyone with whom your father needs to cement an alliance. That is the fate of the daughters of the king. You have always known that, my lambkin.'

`I... but Nyssa, no, we are twins, we are the royal twins, it is different for us!'

`Not that different, my golden one. You cannot marry your brother. I know that you have not broken your maidenhoods, you would not do that. But you are growing up, Cassandra, my bud, my flower, my little lamb. You must find your skills and then leave the Maiden for the Mother and when you do that you must live apart from Eleni.'

`You're wrong,' I said insolently. Her brown wrinkled face contracted into a grimace that looked like pain. `I am a princess of the royal house of Priam and I shall do as I like. I shall marry my brother Eleni and no one shall stop me. No one.'

I achieved a dignified exit, stalking out of the courtyard into the street, my new long tunic swishing behind me. Then I took to my heels and ran, half blind with fury, for Tithone in the lower quarter.

I reached her street, skidded around the corner and ran into her house without even stopping, as is proper, at the threshold.

Tithone was combing her hair. It was dark hair stippled with silver and it spilled around me as I buried my head in her lap and sobbed out the story.

To my horror, it was true. I could not marry my twin.

`But in Egypt...' I sobbed, clinging to the idea that somewhere there was justice. Tithone shook her head. The herb-scented hair lashed my wet eyes.

`No, little daughter, it cannot be. Come. I will show you why. You will not speak until we are out of the house we are to visit, is that clear? Not one word, Princess.'

Tithone called me `Princess' when she was most solemn and usually most angry. I nodded. My world was falling to pieces.

Tithone bound up her hair. The common people thought that there was magic in her hair, and charms made from it were sold in the markets. She found this dryly amusing but took care that no one had a chance to cut a stray piece of it by binding it close to her head and wearing a veil. When I asked her why, she said, `If it is a charm it must be rare.'

I walked behind her, muffling my wet face in a fold of my cloak. We descended the city, out into the ramshackle town which surrounded Troy.

It had grown up largely because the city had expanded beyond its walls. Hector said it also harboured people who did not like the city's rules but who required the protection of the house of Tros and holiness of Ilium. Eleni and me - oh, Eleni my lost love! - had always been forbidden to come there, so naturally we had haunted the place, relishing the strange smells and weird gods and odd languages. There we had learned three phrases in Phrygian and lots of disconnected words, mostly obscene, in a babble of different tongues. Low Town was always interesting. Most of the sailors lived there. It was our favourite part of Troy.

Near the altar to the strangers' gods we turned left, diving down a narrow alleyway redolent of rotting garbage and sewage.

Tithone had often told Hecube, the queen, that unless Low Town was cleansed we would have a plague. In the autumn sun it stank, and flies rose from the unpaved gutter in the centre of the alley.

`Blessing upon the house,' said Tithone, entering a hut made of reeds and driftwood. It was dark inside. I could make out a woman and a baby, and someone else stirring in the blackness. The woman was hushing a newborn, which cried with an incessant grating voice that set my teeth on edge.

`Revered one,' said the mother, `you are welcome.'

`Fire Lady of the Goddess,' said a man's voice. `You are welcome to the hearth.'

Tithone did not even mention my presence, but took the baby out of the mother's arms and carried it into the street. I followed her.

In the street she unwrapped the baby and showed it to me. It was dreadfully deformed.

Ten days old, perhaps. The face was a mask of horror, without eyes, the skull monstrously huge, the arms and legs missing. I bit my lip and did not say a word.

`It will die,' she said matter-of-factly. `Now, hear the mother's tale.'

We went back into the hut and the woman hushed the monster against her breast and asked, `What of the baby, Revered One, Mistress of the Pillar?'

She was awarding Tithone some of the titles of Isis, the Lady of the Egyptians. From her accent, delicately slurred, I took her to be a true Egyptian, not one of the Peoples of the Sea who have settled on the Nile delta and who still speak Danaan.

`He will die in three days,' Tithone said without emphasis. `The gods will take him home. You must spend a month in the Temple of the Mother and then you will be cleansed.'

`We offended the gods,' the woman wailed, and her husband came and held her tightly. `We offended them by leaving the River Land and coming here.'

`Why did you leave?' asked Tithone. The young man answered, stumbling in his speech as though he had lately learned our language.

`Isis knows that we are sister and brother, and loved each other from our one birth.' They were twins! I bit my lip harder. `Bashti and I came down the river and there were the People of the Sea. We left our father because he had sold Bashti to one of the Danaans, curse them with many curses! They caught us and forced my sister, my spouse, then left her for dead, like prey. Me they blinded. She brought us here to windy Ilium, then lay with me after it was clear that she had not conceived a monster of those beast-men. But their seed has corrupted her blood. I hear the wrongness in the child's cry. I have felt its wrong-formed body. We are cursed. Better she had left me to die in Egypt.'

`Better I had died there under their hands,' said the woman bitterly.

`No. Death is never better, daughter,' said Tithone gently. `Wait till this child dies and you are cleansed, then go and lie in the temple of Dionysius and you will conceive a child who will be clean and whole. You, man, must only lie with your wife when she is pregnant. Thus will the curse be removed. How do you live, daughter?'

`We are weavers,' she said, hope beginning to dawn in her voice. I could not see her face. `We have skill to make the finest linen, the pleated gauze that the Pharaohs wear - they call it "woven air". But we cannot afford flax fine enough for good cloth.'

`Come up into the city when the child dies,' said Tithone. `Come to me and I will talk to the mistress of the weavers and she will find you a stone house. Such skill is valued in Troy. Blessings be upon you,' and she went out.

I followed her until we were standing on the bank of Scamander, the river of Troy. Flax and papyrus reeds lined the edge, piping with the bird's cries.

`It was not Danaan's? I asked in a voice as small as the birds'.

`No, daughter.'

`But I could do that - lie down with the god and only lie with Eleni when I was pregnant - could I not do that?'

`Healers must deal with the situation as it is, daughter. Could I tell them that their love was cursed, that the corruption in the woman's blood was the closeness of her birth to her husband?

I would merely have given them both up to death by despair. Their love is the only thing they still have left to them after such long and painful voyaging. This way, they will not conceive any more monsters and can stay with each other. But you, Princess, are not yet compromised. And even if you were' - she knew me well, Tithone my mistress - `even if this night you and Eleni defied the most solemn edicts of the gods of Troy, I would not allow it to continue. After cleansing on barley bread and water for three moons, you would go to the maidens and Eleni to the youths, and you would not see him again until after both of you were safely married to someone else. I could mention to your father, Priam the Lord King, that an Achaean marriage might keep the peace a generation more. Do you want me to do that?'

`No,' I whispered.

My heart was breaking.

Suddenly a god was with me - Apollo the Archer. Sunlight blinded me; heat burned my skin. He was tall, beautiful beyond belief, golden as molten gold from the furnace. He laid one hand on my breast, and I melted in his fire. His voice spoke not in my ears but in my head and reverberated in my womb, which contracted into a knot. Something like a finger penetrated me. `You are mine, Cassandra,' said the great voice. `My ears and eyes in Troy, my woman, my bride. I will lie with you and fill you with my fire. I am yours, and you are mine, Princess.'

Sweet, sweet, piercing sweet, the touch of the god. I opened my eyes and he was gone, but there was a scent of honeysuckle in the filthy street. I trembled as I stood and Tithone bore me up. I leaned on her stringy shoulder, blinded by the light.

`Which god?' she asked, and I heard myself say, `Apollo.' Tithone grunted.

`Go back to your twin, most favoured of Priam's daughters,' she said. `Talk to him. Explain.'

I don't remember walking back to Nyssa's house, but about an hour later I found myself lying beside Eleni in the afternoon heat, trying to explain.

He stared at me, and we embraced with desperate closeness. We clung for an hour, not consoled by the touch of skin on skin. We would never be lovers. I was the daughter of Priam and the bride of Apollo. Eleni and I could not evade our destiny. If we broke all the laws of the gods and of Troy we would only bring forth monsters.

Then a vision came to Eleni, which I shared. He had flung himself over onto his back, out of my arms, and a golden woman appeared, lying beside him. My twin's eyes widened. She was beautiful beyond compare, glowing with life. Her hair hung down and brushed his breast and left delicate scorched lines where it touched. She laid both hands on his shoulders as she leaned over to kiss his mouth. I heard his breathing shorten and his pulse raced in the wrist I held in my hands.

`Mine,' said the woman. `Eleni, you are my husband, the creature of my heart.' I was suddenly reminded of someone, a mortal woman like myself. The bones of the face and the way she framed words; the curve of the mouth and the way her hair hung down as though it flowed like water. I could not catch the resemblance. Eleni was transfigured. He was as beautiful as the goddess. She reached up and unpinned the chiton. Naked, she was perfect. Eleni gasped something and held out his arms. Ishtar the goddess knelt over my brother and her smooth flank and thigh touched mine, the golden skin as hot as metal. For a moment she towered over us, Eleni supine and me clutching him from the side. Then she bent and kissed him; once on the mouth, once on the belly, once on the phallus.

Then, as I lay and could not breathe, she sank down on my brother, engulfing in her sheath the phallus I could never have. I watched as it vanished. Eleni cried as if in pain and stiffened until I thought his back would break. Once, twice, the phallus slipped into the sheath. Then she said, `You will lie with me again, Eleni the Trojan - not with your twin, but with me,' and she vanished.

Eleni threw himself into my arms and kissed my mouth and I had barely touched him when he reached his climax and sank onto my breast to weep as if his heart was broken. Thus in tears we discovered that the love of the gods is shattering for the mortals whom they favour. We wished that we had been born apart and unrelated, and that we had never attracted divine attention.

But we knew as we wept that we were fated. That night we lay down with Hector on the roof of the palace. Alexandratos, our brother, whom we called Pariki, the purse, after the shepherd's bag he always carried, was sitting with his back against the bull's horns which crowned the roof.

Pariki was eighteen, a vague and dreamy youth, with a streak of cruelty. Eleni and I did not like him; he had nasty fingers which tweaked and tickled when no one was watching. Luckily he was about to leave on a trading mission to Sparta and Corinth. Pariki had the grey eyes of the god-touched and long golden hair which he was very proud of, arraying it across his smooth shoulders. The only skill he had so far envinced was the Dionysiac one of making love; at this his repute was very high. This did not concern Eleni and me and one of the most satisfying moments of our childhood had been the contrivance which spilled oak gall distillate on Pariki's pretty head. It had dyed his hair black for some months. We reckoned it worth the spanking we had got from Hector for wasting his Egyptian ink. Typically, Pariki would never say that he liked Hector's stories, but he often happened to be on the roof when we came there to hear them.

Andromache had joined us that night. She was twelve too, taller than me, and we were glad that she was there because Hector knew all about what had happened to us and we did not want to talk about it. Because Andromache worshipped our brother and would be married to him in spring, we yielded the place on his left side, nearest his heart, to her. Eleni lay behind me and Státhi reposed in his customary place on the warrior's chest.

I was meanly pleased that Státhi did not treat Andromache any better than the rest of us. He scratched her just as hard if she tried to touch him. Since Státhi slept every night with Hector we wondered what he would do to the maiden when she came to the warrior's bed.

Then I saw how Eleni looked at Andromache and nothing seemed funny any more. The face and form of the woman in the vision had seemed familiar; now I knew. The goddess had taken Andromache's form to seduce my brother. He was in love with her.

And she was in love with Hector, Bulwark of Troy, eldest son of Priam. It was the first time the gods had played games with us. We were desperately vulnerable and hurt.

Andromache snuggled into Hector and demanded a story.

`What story, children?' he asked amiably. `Gods?'

Eleni and I shuddered. `Not gods.'

Hector's face changed; he noticed our reaction. `Andromache shall choose,' he said gently. `Come closer, twins, you are cold.' His chest was bare and his flesh was dry and warm. I rubbed my face against his shoulder, feeling the thick pad of muscle over the bone, and his arm encompassed Eleni and me.

`Heroes,' said Andromache. Hector chuckled. `Which hero, little maiden?' he asked `Perseus? Theseus?'

`No, Theseus is a cheat,' said Andromache, who had strong opinions on honour. Myrine said that she thought like an Amazon, which was a great compliment from Myrine. `Heracles.'

`Ah, well. There are many stories about Heracles.' Hector sat up a little, his back against our rolled cloak, causing Státhi to slide down his chest, make a short, disgusted exclamation and leave red furrows in his wake. Hector rearranged us with Státhi on his lap and began in his storyteller's voice.

`Once there was a great hero who came to Troy to seek horses from Laomedon, our grandfather, king of Troy.'

We had heard this story before but we liked hearing stories again. The first hearing you are too excited and long for the resolution; the second time you can pay attention to the story. Andromache wrapped herself around Hector while Eleni and I, desolate in the wake of the shattering of our marriage and our encounters with the god, embraced closely, his belly against my back and my face buried in Hector's chest.

`They will call me Hector Sibling Coat if you get any closer,' he commented. `Now, to the story. Laomedon was the fifth king, descendant of Dardanus who received the divine horses in exchange for his son Ganymede. Laomedon inherited the herd; all subsequent kings had bred them wisely and they were the best horses in the world.'

`They are still the best horses in the world,' declared Andromache. She was a better rider than any of us - probably better than any Trojan warrior. She seemed to have an instinctive understanding with her mount. I had seen her leap onto the shaggy back of a wild stallion, a lord of horses, just brought in from the summer pastures, and tame him into willingness, if not submission, on one wild ride. I could ride adequately, as could Eleni, and our brother Hector could drive a two-horse chariot with as much ease as a child drives a wooden toy.

We had always wondered if part of his charm for Andromache was that he had promised to allow her to drive his own prized chariot pair, whom no other hand was allowed to touch.

`Heracles was the son of the Achaean father god, Zeus, the stern one, compeller of the clouds,' Hector continued, `and Alchmene, a Danaan woman from the Tiryns, which is girded with walls. The hero's companions were Telamon and Iolas and the men of Tiryns, and he came with six ships through the straights, which we thus call the Pillars of Heracles. They arrived at a time when Laomedon had broken his bargain with Poseidon.'

`What was the bargain?' I asked ritually.

`Laomedon had offered six of his horses to Poseidon if he would build the walls of Troy. The god agreed. But when the king could not bear to part with the horses, Poseidon sent a sea monster so ravenous it bit the keels out of boats and swallowed crews whole.'

Hector paused dramatically, then went on. `An oracle commanded that the Princess Hesione, daughter of the king and sister of our father King Priam, be chained on the shore for the sea monster. This sacrifice, the oracle said, would appease Poseidon Blue-Haired, whom Laomedon had cast from the city.'

This was troubling, as we in Troy did not sacrifice living things. Our gods did not like such sacrifices. Only the barbarian Achaeans burnt dead flesh and spilled blood before their cruel gods.

We gave seed and flowers and garments and gold to the gods of Troy, and honey and wine; only once a year did a creature die for the gods. That was the bull which was sacrificed to Dionysius, at the festival which marked the turning of winter to spring. We garlanded the perfect bull with flowers and brought him from his stall to die for the season. Then we ate his flesh and drank his blood mingled with wine which made the whole city drunk, giving our fleshly worship to the god of increase and wine. The Dionysiad lasted for three days and even the maidens of the goddess and the man-loving priests of Adonis danced and coupled in the squares, for a god must have his due.

Hector continued, `The hero Heracles sailed into the bay and saw the princess chained to Scaean Gate where the oak tree grows. Telamon seized Hesione, and Heracles bargained with the sea monster which began to rise beneath the Achaean ship. It was bigger than the ship, and angry because it was baulked of its prey.

Its head came out of the water and it grabbed the mast, snapping it and chewing the sail. Laomedon had promised horses if the hero could kill the monster.

`Heracles bound on his bronze armour and his helmet and took his spear and his sword, and as the monster's head came around leapt full into its mouth. The Achaeans wailed as its teeth snapped shut over him and it dived beneath the surface again. But Telamon had Hesione and wanted her, though he had made no bargain for the king's daughter.

`In the waters of the bay, the Trojans saw the monster writhing and twisting. It was the length of three ships, as broad in the middle as two, and it roared fearfully, so loud that the guards on the Scaean Gate covered their ears. The Achaeans began to mourn for their hero, wailing and beating their breasts, when the monster gave a convulsive jerk and Heracles the Hero hacked his way out of its belly, so that it spewed its guts and stranded, dying messily in the shallows.

`Later it took all of our fleet to drag it into the deep water so that the tide could bear it away.

`Heracles came alive out of the monster and walked, dripping scales and fishy blood, up the steep streets to the palace to demand his promised price. The Achaeans and the Princess Hesione followed him. Laomedon the horse-lover refused him his reward, again breaking solemn oaths sworn by the gods. Standing in the throne room with his sons all about him, he defied the hero and bade him begone with insulting words. Heracles was possessed of battle fury.'

`What's battle fury?' Eleni interrupted.

`He lost his mind, all knowledge of himself, and killed everyone standing,' said Hector. `He killed the king and all but one of his sons. His sword moved like a reaping hook, cutting down the youth of Ilium. They ran and he pursued the royal house of Tros, breaking down the walls, pulling stone from stone and killing when he found them, with sword and spear and hands and teeth. Stones bounced off him, spears could not pierce him, swords broke on his invulnerable body. Then the Princess Hesione caught the remaining child - Podarkes swift-foot, who had run for his life - and held him to her breast and defied Heracles to kill him. Heracles, servant of women, could not touch her. He ransomed the child for her gold-embroidered veil, the maiden's veil which girls wore at that time. Thus Hesione's body, freely offered, appeased the hero, and he lay down with her in the rubble among the bodies of her brothers. It is said that although he was mired with blood and stronger than the sea, he did not hurt her as he lay with her. Heracles, goddess-brought, was sworn not to harm women.

`Hesione ordered that horses should be brought and given to the hero, and gold to Telamon and the men of wall-girt Tiryns. This was done. Hesione gave the child, whom she named Priamos, one who is ransomed, to Lykke the wolf-woman to raise, ordering her to take him into the mountains. She appointed the eldest princess to rule until Priamos returned. That Priamos is our father, the Lord King Priam the old.'

`What happened to Hesione?' asked Andromache. Hector did not answer immediately, but stroked a living hand down the girl's side and kissed her on the mouth. Behind me Eleni muttered. I turned and kissed him, afraid he would make some unfortunate comment. It was the first time that I did not know for certain what Eleni would do.

Hector said regretfully, `Telamon kidnapped her. Heracles, possessed by remorse for his murders, re-built the walls, as you see them now. While the hero was hauling stone, Telamon of Tiryns stole Hesione, Princess of Troy and sailed away with her.

`The princess sent word that we should not pursue her; she had no wish to start a war with the barbarians. Heracles finished the walls and went home. There, possessed of that same fury, he killed his own children and was set twelve labours, the labours that made him a god.'

`And Hesione?' asked Pariki's voice, stilted as though he spoke though clenched teeth.

`She lived with Telamon for the rest of her life and had many sons,' said Hector. `It is an old tale, brother.'

`It is an insult which has not been avenged,' said Pariki. He stalked away. We heard his sandals slap against the stone steps of the palace staircase.

For some reason Hector would tell no further tales that night. He held us close, as though he feared to lose us.