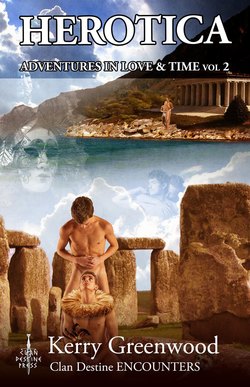

Читать книгу Herotica 2 - Kerry Greenwood - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE PAINTER AND THE POTTER

Оглавление221 BC

‘He’s going to kill all of us, you know,’ murmured Gao P’in Te to his best friend, Pan Liang. His voice was low and without sibilants. They had learned to do this well during the blood-soaked reign of the Tiger of Chi’in. An unwise whisper could condemn whole villages.

Only because the two – Gao the Painter of Faces and Pan the Master Potter – had always been companions and needed to consult with each other frequently about the tomb figures, were they allowed to sit together, drinking Iron Goddess tea, and talk without someone listening in. The emperor had a multitude of ears at his service. Terror was a great spur to attention to duty.

Gao P’in Te didn’t think there was a lot of luck around at present, and didn’t wish to press it. Pan nodded imperceptibly, sitting close to his companion. He loved Gao with a whole heart and had for nearly ten years, since they had first lain down together. Every one of the most beautiful of the Emperor of All China’s terracotta cavalry had the face of his lover, core of his being. He could feel the warmth of Gao’s thigh in his working cotton trousers, against his own sturdier, heavier limb, gnarled with toil. Gao was graceful in his movements, with beautiful hands. Pan was stocky, strong, and not terribly clean, after a day in the mud pits where they were constructing the army to guard the emperor’s rest. His hands were ugly with broken nails and he tucked one under his arm when he saw Gao looking at it.

‘Then we can at least die together,’ he replied.

‘I would rather live together.’ Gao slid an arm behind Pan and stroked his back.

‘You have a way to do this?’ asked Pan Liang.

‘If you will leave it all behind: family, business, son. All of it.’

‘For you?’ asked Pan.

Gao looked into his face, then shifted his eyes, looking down.

‘I will understand if you need time to think about it, my lotus, but the King isn’t well and they are saying that he’s been taking alchemical potions, and they have a lot of mercury in them, he’s going mad–’

‘Yes,’ said Pan, spilling tea on him and using the mopping process to caress Gao’s chest. ‘Yes, of course. I don’t need to think about it. What should I do?’

‘I should never have doubted you. Forgive me,’ whispered Gao. ‘We shall have to make it appear that you have been murdered, and that I have committed suicide out of despondency. We don’t want anyone deciding to execute your whole family on the notion that they might have killed you, if we just flee.’

‘And we are fleeing to…?’

‘I have a place in mind. When the Emperor departs, his empire will depart, too. It’s only glued together with blood – our blood. I wouldn’t give it ten years. I know somewhere safe. Trust me?’

‘Always,’ said Pan. ‘When?’

‘Tonight. Bring anything you absolutely cannot leave behind. A change of clothes, your simplest. And gold. Tell no one at all. The path outside your house, where you walk at night; at dead of night, I’ll be waiting.’

‘I’ll be there. Let me pour you some more tea,’ said Pan, more loudly. ‘I’m very sorry about the shirt, I’m sure it will wash.’

‘You’re so clumsy,’ complained Gao, as the proprietor of the tea shop passed close enough to hear.

Seven hundred thousand labourers worked on delving and piling the three great mounds under Mount Li, and more toiled in the jade mine, the gold mine, and the smelting, carving, painting, moulding and arranging of the great labyrinth in which the Emperor was – eventually, if his quest for eternal life failed – going to consent to be buried. Into the tomb would go not only the emperor’s corpse but, living, all of his wives and concubines who had not borne children, all of his officials and advisors, and all of the men who knew the secrets of the tombs. Some of this had been announced, but when Gao saw huge iron doors being installed at the end of certain corridors, he knew his days were numbered.

All books in the new Kingdom of Ch’in had been burned. Four hundred and sixty scholars had been buried alive, and learning was greatly reduced. But artists were allowed to keep copybooks of the best artistic styles. Gao had two books, a number of robes, some gold and jade and his paints. That was all he intended to take. It made a small bundle. Not much for a lifetime. He added a wide piece of coarse cloth, a pot of pig’s blood and a shovel.

He left his small house, cached his bundle near Pan’s house, and went back to the pile of dead workmen who lay beside the road, waiting for the cart to carry them away for burial. With the greatest effort of his life – for he was a fastidious man, he had even changed the tea-stained shirt – he rolled the dead over, seeking one who could resemble Pan Liang well enough to pass a cursory inspection. Death was common enough in this work camp. No one would enquire too closely.

He found a man who must have been a stalwart; stocky and much like Pan Liang in body. The corpse had died of a head wound, common amongst the tunnelers. Gao stripped the body, wrapped it in a length of calico, and slung it over his shoulder, heading for the appointed spot. His friend was waiting for him. Gao could hear him breathing.

Gao kissed Pan Liang on the mouth, hard and fierce. Then he watched as Pan stripped, and put his clothes on the corpse, handling the stiffening limbs with shuddering disgust. Finally the dead man was arrayed, even to Pan’s hat and ear drops and the gold rings on the gnarled fingers. Pan was dressed in clothes which any workman might own. He had stout leather boots and carried his bundle in a sling.

‘There’s one more thing,’ whispered Gao, leaning on him. ‘They have to think he’s you, so we have to...’

He picked up the shovel. Pan understood instantly.

‘No, no, you’ll ruin your hands, using a spade,’ he whispered, turning Gao so that he faced away from the body. ‘I’ll do it. Block your ears.’

Even so, Goa heard the dreadful crunching smash as the corpse’s face was caved in. Pan threw the spade into the undergrowth, where it would be easily found, and poured the pig’s blood out in a wide, arterial spray.

‘How, let’s get on with your suicide,’ he said, wrapping an arm around his friend’s shoulders and leading him away. He was carrying the cloth and the container.

Gao was trembling. That’s the trouble with these artistic types, thought Pan, flooded with affection, hugging Gao tighter. Brilliant minds, but they demand too much of a fragile body. That’s why he needs me. We’re one. He’s the mind, I’m the body. He thinks us out of trouble, and I carry him when he faints.

‘I would have, you know,’ said Gao, as he took off his outer robe and his ceremonial hat, shedding his official jewellery and piling it all on top of his shoes. ‘If you had been killed, I would have died with you.’

‘Well, that’s not going to happen now, is it?’ said Pan Liang comfortably, sinking the pig’s blood container and washing his hands. He flung Gao’s robe and hat out to float on the water, artfully snagging one hem so the site of this lamentable suicide would not be missed. ‘Now, get dressed, Master, you give me that bundle, I’m your man and I do the carrying. I’ll keep this bit of canvas, it might come in useful. Now, which way?’

‘This way,’ replied Gao, blinking back tears. Without Pan, he would not deserve to survive. He had taken the dreadful task away from his friend, without complaining and without despising Gao as weak. He was a wonderful man, his Pan Liang. ‘It’s a long way, but it won’t be too uncomfortable. I never asked, but can you drive a water buffalo?’

‘Since I was five years old, Master,’ replied Pan, and grinned.

Gao halted, dropped the bag, and kissed him again.

Thirty days later, they were far south, nearing a strange area of mountains and rivers. They had settled into their journey, which seemed to have been going on for years. Gao no longer woke, shivering, with the nightmare memory of that spade. Pan lay next to him in their small inn, sleeping his light potter’s sleep, which would rouse him at the sound of a crackling from the kiln.

There had been two close calls, Gao thought, lying back on the pallet with his arms behind his head. They had travelled at buffalo pace along roads thronged with messengers, soldiers, peasants, traders and farmers. They had attracted little notice, a minor nobleman and his peasant companion on some sort of family business. One guard was suspicious, and Gao immediately went right up to him, talking about the death of a distant uncle and the tedium of travelling to deal with an estate. He burbled about how distraught his poor sister must be until the guard’s eyes glazed over and he let them pass. Gao and Pan had nearly burst, not laughing until they were quite out of earshot.

The serious one had been when a travelling patrol had grabbed Pan Liang. The Emperor wanted workers on the Great Wall and seized any peasant who seemed unattached. It had taken a state visit by an enraged and terrified artist, flourishing an expertly forged Secret Service seal, to retrieve him, standing meek and patient, roped to a train of other meek and patient men. After that, they went on all night, despite the complaints of Little Flower, the buffalo.

That seal had been a work of great skill. Gao had only had a passing glance at the real one, but he had a very good trained eye, and he was fairly sure that it would pass inspection. He sighed, still terrified at the thought that his friend might be so easily removed from him. Two more days should see them at the house.

Pan stirred. Gao snuggled back into his arms. They folded around him, as though they had been measured for each other.

Three days later – Little Flower had chipped a hoof on a stone, and needed to rest – they arrived at a small house, tucked away behind several gardens, right against one of the strange mountains, which went up like a wall but was only three paces wide. The house had a winding path, a roof with red glazed tiles and the correct demons on each corner. The door was opened by a rounded old lady who showed them, as though it was her own, the plain, clean spaces, the fine wooden shutters for the cold weather, the piles of garments and feather mattresses, and supper laid out, the fire already lit, a kettle already boiling. Outside was a bath house, with a sunken tub decorated with butterflies, and a strong inrush of naturally hot water.

Then she bowed to Gao and departed. It was nice to have the little house occupied by such a pleasant young man, and one free with his gold.

‘Here we are,’ said Pan bracingly, putting down his bundles. They had left Little Flower and the cart at a stable in the village. ‘Come along, Master. You need a bath. I really need a bath, I stink. I’ve been wearing these clothes since we left Xian. You painted those butterflies, didn’t you, my Te, my own love?’ Pan had dropped the peasant voice, and that shocked Gao out of his bemusement. The journey was over. They were home; at last.

‘I painted them for you,’ faltered Gao, allowing Pan to lead him to the bath house and strip off his clothes. Pan was already naked. He thought the only thing he could do with those utterly filthy clothes would be to nail them to the mountain in case they came alive during the night. The water gushed over them as they sank down into the bath, embracing, laughing, and sighing with relief. Kissing with relief, with joy, with passion.

The emperor died and was entombed with his multitudinous sacrifices. Gao obtained paper and began to paint again, secretly. He didn’t give the empire very long, but he had to stay hidden until any leftover inquisitors had burned out. Pan took to poetry. He was very good. He loved words. Gao woke many mornings to find Pan gone – walking in the mountains, seeking fresh air and new plants for his garden – and to find a poem pinned to Pan’s side of their bolster.

Thirty years after their arrival in their village, which they always celebrated as a day of special festivity, Pan woke and found Gao not there, but a poem pinned to Gao’s side of the bolster.

I see him seated at the writing desk

Head bowed, brush raised,

Thinking. Then with fluid suddenness he writes:

The characters dance like swallows in the summer sky.

Long ago we said, Forever, and lay down together.

So this is my forever, which floods my heart:

The poet’s brush celebrates my humbleness,

As the painter’s brush celebrates his most splendid presence.