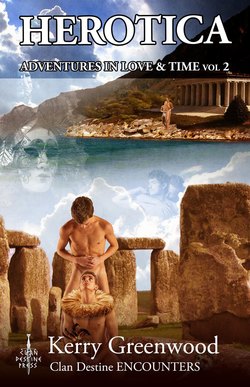

Читать книгу Herotica 2 - Kerry Greenwood - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CARNEVALE DI VENEZIA

ОглавлениеGiovanni ‘baci baci’ di Ca’ Nuova knew that he shouldn’t have taken the bet. He was well known amongst the Honourable Company of Gondalieri as able to seduce anyone, absolutely anyone - though he drew the line at confessed religious - with his flashing smile, his curly hair, his beautiful brown eyes and his strong, flawless body. He could sing like a very licentious thrush and charm aged dowagers and stern members of the Consiglio di Deci as well as pretty girls. Or boys. Gio wasn’t fussy.

But the Alchemist, now, that was a steep proposition and he had fifty escudos riding on the result. And he didn’t actually have fifty escudos. So he had to succeed or be dishonoured.

The Alchemist was Lorenzo di Bianchi, the son of a very distinguished household. They all lived in the Ca’ D’Oro. Gio went past there every day, on his lawful journeys. He saw the pale, strange face of the young man staring out of the window, high up in the great house. Gio found after a few days that he couldn’t take his eyes off Lorenzo di Bianchi. Fortunately Giovanni was a very skilled gondolier, and had avoided collisions, however narrowly. He smiled at the pale face as he passed, but Lorenzo never even seemed to see him.

And how to meet him was the first difficulty. Such elevated persons never came down to the level of a gondolieri, not to speak, unless it was to order their servants to tell him the address to which they wished to be conveyed. Those who proposed the wager had agreed to allow it to stay on the table until carnevale, when all ranks mixed and all people were masked. Gio had previously made a beast of himself during carnevale, wallowing in all that freely-offered flesh. This time, he was focused on one object. Lorenzo di Bianchi was going to be his.

If he joined the carnival. If he actually came out of the Ca’ D’Oro. Giovanni had scraped acquaintance with the people who know all: the servants at the great house. Never difficult for a young man with a beautiful grin, a gondola, and a willingness to do small errands for overworked kitchen staff for no fee. They gossiped about Lorenzo. The rest of the family was ordinary. The Signore’s wife was expecting, again, the elder son of the house was in disgrace for gambling, a ship had been lost in the Atlantic. Il Signore had invited Veronica, the great courtesan, to attend the first party of carnevale. The cook, who had grabbed the bunch of oregano she needed out of Gio’s hands and pressed it to her bosom as though it was a bouquet, sighed.

‘Poor Lorenzo! It’s for him that Il Signore should be calling a courtesan.’

‘Oh, why?’ asked Gio idly, picking up pastry crumbs from the table with one finger.

‘It’s well known that he’s a virgin! And not interested, either, or so they say. Just does experiments all night and sleeps all day, when he sleeps. Hardly eats a crumb of my good food.’

‘A man of no taste,’ commented Gio, biting the fritelle which the cook had handed him, taking the hint without intervention of thought. Giovanni’s seduction methods somewhat relied on automatic reactions. The cook shook her head.

‘No, no, poor boy, though he’s so fussy when he does eat. Can’t abide garlic. I have to cook special dishes for him. Though he’s got a sweet tooth. He always eats my rosamela pannacotta. But a man can’t live on cream, can he? And he’s engrossed in his studies. Trying to find the philosopher’s stone, they say. His mother has made him promise he’ll at least come out for carnevale.’

‘Oh? What mask will he wear?’ asked Gio.

‘Probably Medico della Pesta. La Signora sent up a selection and he seemed to like that one. But he says he’s going alone. He won’t travel with his family. Poor boy, he’s mad. The Bianchis go to all the best parties.’

‘Then he will need a gondola,’ said Giovanni, suppressing an internal squeal of joy. ‘And who better to trust the son of the house to but your most reliable and humble servant?’

The cook beamed.

‘Oh, Gio, would you look after him? I worry about him, he’s very clever but hasn’t the sense of a newly born mouse.’

Giovanni ‘Baci baci’ di Ca’ Nuova felt like a hypocrite when he accepted the cook’s hug and agreed to look after Lorenzo.

Then again, he intended to look after him.

From his family home in the Calle di Turchetta, a spruce and combed Giovanni set forth at the appointed time. Eight of the clock on a cold, damp winter’s night. Giovanni was not cold. He had chosen a Zanni, with jester’s hat, as his mask. It made him ugly, but it left his mouth free to eat and drink - and to kiss, should it come to that, St Lucy willing, though as a virgin martyr Gio wasn’t so sure that he ought to be praying to her for this favour. He switched his prayers to Peter. Peter was a fisherman. He’d understand.

The cloaked figure was waiting at the watergate. It stepped into the gondola easily, which made Giovanni frown. He leaned forward to adjust the leather covering, and pressed a delicate kiss to the mouth just visible under the grotesque mask. Then he said softly ‘Who are you, and where is your master?’

‘I’m Lorenzo di Bianchi,’ protested the man.

‘No, you’re not,’ said Gio. ‘Tell me, I might be able to help.’

‘Luisa della Cucina likes you,’ sighed the man. ‘All right. I’m Cosimo, his valet. His mother made him promise to go out. He doesn’t want to, so I said I’d go in his place.’

‘And what will you give me if I don’t tell La Signora about this?’ bargained Giovanni.

‘Anything, please,’ begged Cosimo. ‘He’s scared to go outside. He sweats and shakes. Just take me around a bit, let me be seen at various places, and then bring me home.’

‘If I do that,’ said Gio, ‘I want an interview with Lorenzo Di Bianchi, alone. Tonight.’

‘All right,' gasped Cosimo, and kissed him back. Well, that answered that question. Cosimo was not Lorenzo’s lover. He tasted far too strongly of garlic.

‘St Mark’s,’ agreed, Gio, and stepped back to his rowing platform. He had to pay attention. The wide waterway was jammed with gondolas. Various friends rowed past, each grinning as they saw someone who was expected to be Lorenzo di Bianchi in his vessel. They had more faith in his skills than Gio had, at present. Too afraid to go outside? Was it even proper to seduce a madman? Cosimo would suffer no injury if he seduced him. But Lorenzo?

Gio worried at the problem as he rowed the spurious Lorenzo to St Marks, where he danced amongst the brightly dressed, and then to a couple of private parties, where his Plague Doctor’s mask made it impossible for him to talk clearly, and then, after three hours, home to the Ca‘ D’Oro.

Gio slid the gondola into the mooring in front of the watergate, deposited Cosimo, then took it away to an unobtrusive, common place to tie up. He stepped lightly back to the door, where Cosimo still waited.

Then Cosimo, displaying more intelligence than Gio had expected, flung his cloaked arm around the gondolier and brought him into the house, shutting the door behind them, a signal for any watcher that the carnevale celebrator had found his friend for the night. And would not want to be disturbed.

They raided the platters of festival delights left out in the kitchen, gobbled quite a lot of them, and carried some with them.

They climbed a lot of stairs in the half dark until they reached Lorenzo’s rooms.

‘I’ll be next door,’ whispered Cosimo. ‘If he doesn’t want you, come to me?’

‘Deal,’ agreed Giovanni, and opened the door.

The pale young man was reading by the light of a shielded candle. Gio appreciated that it could not be seen from the canale grande, as the owner was supposed to be out enjoying the carnival. He looked up when Gio came in and put his plate of rose and honey pannacotta, fritelle di mela alla vaniglia and cannoli on the table, pushing aside several heavy books.

‘Happy carnival!’ he said. The young man shut the book with a thump.

‘Was Cosimo caught?’ he asked tensely.

‘Only by me, and I helped him with his charade. Come, try these vanilla fritelle, they are very good.’

‘Why would you do that?’ asked Lorenzo di Bianchi, fingers irresistibly attracted to the sweet cakes.

‘Because I hope to seduce you,’ said Gio, smiling his best smile.

‘Your hope is vain,’ said Lorenzo, ‘and you have lost your wager. How much will you lose?’

‘Fifty escudos,’ replied Gio.

‘Which you don’t have,’ the young man continued.

‘True again,’ confessed Gio.

‘What made you make such a wager?’ asked Lorenzo, noting that Gio was standing between him and the platter of cakes.

‘I saw you in the window every time I went past. You are beautiful, with your beechnut hair and your sad eyes and your red mouth. And generally I can charm a kiss from anyone. Then I discovered that - you are not able to come out of the house. Which made me feel bad about my plans. It is not proper to seduce ... one whose mind is afflicted. That isn’t in the game. Just like children or nuns. So the bet is off,’ said Gio, ‘and so am I.’

‘Wait,’ said Lorenzo. ‘How did you find Cosimo out? You couldn’t see his face and he’s the same height as I am, wearing my clothes and my mask.’

‘The mask didn’t fit exactly, they are moulded specially to the face. He stepped far too gracefully into my gondola for someone who rarely goes outside. And he smelt of garlic, which Luisa della Cucina says you can’t stand.’

‘That was very clever,’ murmured Lorenzo.

‘At your service,’ said Giovanni, made a magnificent bow, and was caught at the door by Lorenzo’s arms slipping around his waist and clasping him close.

‘You could, of course, win your bet,’ murmured Lorenzo.

‘At,’ gasped Gio, between kisses ‘your,’ kiss again, ‘service.’

Two hours later they were naked, sated for the moment, sitting up in Lorenzo’s magnificent bed, eating fritelle and licking the spilled honey off all available skin. And Giovanni ‘baci baci’ Di Ca’ Nuova, irresistible seducer of all mankind, had fallen completely and hopelessly in love. Lorenzo di Bianchi had to review all that his philosophers had said of love, which he had previously thought overdrawn and now seemed scarcely adequate to describe how he felt.

No one particularly noticed that every day ever after Giovanni ended his day’s work not by returning to the overpeopled house in the Calle Di Turchette but by making his way up the secret staircase of the Ca’ D’Oro, there to make love for as long as Cosimo could keep the door. Lorenzo pined for him when he was gone, and Gio came back as often as he could.

Then Savanarola arrived in Venice, and Bonfires of the Vanities were made, and the canals and streets were full of fears and denunciations. Giovanni’s family had connections in Tuscany. Letters to the Toscana went back and forth. Other connections in Naples were contacted. Gondoliers were not people who intended to see their life’s work burn because some renegade priest thought that their boats were pagan. Before Holy Week began, the boats were gradually taken away to be hidden on various islands and gondolas began to be less in evidence. Many citizens of the Serenissima were inconvenienced. In the gondolier’s view, this was only right and proper for their entertaining of such idiotic views.

Giovanni was returning from a trip out to the Lido when his brother caught at his sternpost and yelled, ‘Your boy is denounced, get him out to Uncle Teodoro right away!’ and Giovanni rowed for the Ca’ D’Oro as though he was competing in the regatta. He ran up the stairs to find Cosimo sitting on the top step, shivering. He caught Giovanni’s arm in an iron grip.

‘Oh, Gio, thank God you’re here. They’ll come for him, but he can’t bring himself to escape into the open,’ he whimpered. ‘What shall we do?’

‘If I have to, I’ll knock him unconscious and carry him,’ retorted Giovanni. ‘Let me in, Cosimo. Keep the door.’

‘Oh, my own love, how shall we manage?’ asked Lorenzo as he came inside. ‘I can’t go out, I can’t, I’m so sorry but...’

Gio gathered him close in a comforting hug which stilled his trembling.

‘We’ll think of something. We also have to make sure that no one comes searching for you. I have just the notion. Do you have a really strong sleeping drug? One that might mimic death to a careless observer? And some paint. Quickly!’ said Giovanni. ‘Or they will be taking two of us to the stake.’

‘Oh, no,’ Lorenzo’s eyes widened. ‘No, you had nothing to do with the studies they are calling black magic.’

‘You think I’d live without you?’ demanded Giovanni. ‘You think I’d let you burn alone? Quick, sleeping draught, paint. Oh, tesoro mio, we will live through this. I promise. ‘

Lorenzo rummmaged and produced a phial of green liquid and a box of paints. Giovanni bade him loosen his doublet and lie down on his bed cover. He called the valet inside.

‘Cosimo, come in and pack up all the books, his clothes, all that stuff, when we are gone. Weep convincingly - Luisa will give you a cut onion - and bring them to my uncle’s house, here is the address, as soon as you can. Here is money. It is all yours. Why is Il Signore allowing this to happen?’ he asked, swiftly painting his lover’s face like a carnival mask of il peste, the plague, with green underpaint and horrible bursts of scarlet and yellow.

‘That looks really dreadful,’ commented Cosimo. ‘The elder son is the favoured one. Il Signore thinks he can sacrifice one to Savanarola and preserve the other. It will probably work,’ he added.

‘Do you trust me?’ asked Giovanni of his lover, now a figure of horror and nightmare.

‘I trust you,’ said Lorenzo. ‘I love you.’

‘I love you, too. Take the potion. I’ll see you soon.’

Lorenzo took the potion.

Great weeping and lamentation echoed down the canale grande as the di Bianchi family learned that their strange, unloved second son had expired of the plague, thus meaning that they would all be shut in for a month, avoiding any more interaction with Savanarola. Il Signore, handkerchief over nose and mouth, had farewelled his dead child, lying ghastly and unsightly on the floor, from a safe distance and bade them take the corpse away. Cosimo and Luisa’s son carried the body, wrapped in its bed cover, down the stairs and out into the capacious seating of one of the few gondola now operating in Venice. Giovanni caught a very speaking look from Luisa as they laid the body down gently.

She gave him a covered basket such as are used for journeys and kissed him like a mother.

Then he was rowing down the Grand Canal as always, towards the lido and a boat which was waiting to carry them both to Uncle Teodoro in Napoli. He was flying the black flag which meant plague, and no one interfered with his progress. He reached the lido, gave his gondola to his cousin, and carried Lorenzo into the hold of the boat, which set sail swiftly.

Unwrapped, Lorenzo was deeply asleep and did not react as Gio cleaned the paint from his face. He did not stir until they were rocking at anchor off the Amalfi coast waiting for dawn. Giovanni was very worried about whether his lover would wake at all, and about if he did, how he would feel, now being away from his precious house and his books and his safety. A safety which would have seen him sacrificed to family ambitions, but safety of a sort.

So it was a great relief when Lorenzo opened his eyes and said, ‘It worked,’ and began to cry.

Gio lay down next to him until sobs passed into sniffles.

‘Where are we going?’ asked Lorenzo, wiping his face on his shirt sleeve.

‘Naples, to my uncle Teodoro. He’s a shipwright. I’m a gondola builder. We will be comfortable there. My father has lent us a house. Are you hungry? Luisa sent a basket.’

‘Very hungry,’ agreed Lorenzo. Gio opened the basket. It contained pannacotta alla rosamela, cannoli and fritella with vanilla and apples.

‘She was always a clever woman, that Luisa,’ mused Lorenzo, biting into an apple fritter and closing his eyes in ecstasy. ‘I shall have to work hard, if I am to buy new books,’ he said sadly.

‘No need,’ Gio swallowed his cannoli. ‘Cosimo will come with the books and all your other goods. I gave him the money to travel to Naples in style.’

‘How much money?’ asked Lorenzo.

‘Fifty escudos.’

‘That’s a lot of money,’ observed Lorenzo.

‘Yes,’ said Giovanni ‘baci baci’ Di Ca’ Nuova. ‘Didn’t I tell you? I won a bet.’