Читать книгу Abode of the Gods - Kev Reynolds - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

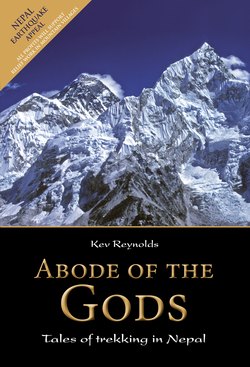

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

Kangchenjunga

THE MOST BEAUTIFUL WALK IN THE WORLD (1989)

A first visit to the Himalaya and the fulfilment of a dream, as I trek to the base of the world’s third-highest mountain.

‘Halloo! Bed-tea!’

It’s almost 6 o’clock as light seeps into a November morning, our second since leaving the road-head. For several minutes I’ve lain here awake, comfortable in my sleeping bag listening to sounds of the new day, reluctant as yet to trade this warmth for what will probably be more of the damp mist of yesterday and the day before. That mist had denied us mountain views, save for one brief, tantalising moment when from the broad crest of the Milke Danda the veil shredded to reveal distant clouds and a hint – no more than that – of a line of Himalayan snow peaks out to the northwest. Then the mists closed in once more. Blinkered, we’d stumbled on, wondering.

This morning there is no wind, the tent is stilled, a vague glow brightens the fabric to tell of daybreak, and as I receive the steaming mug through the doorway, I see beyond cook-boy Indre’s beaming, high-cheekboned face (‘Morninggg, velly nice morning sah!’) to a shallow pool trapped in a tiny scoop of a valley among the foothills. Yesterday the water seemed brackish, but now from my vantage point a dozen paces away, I can see that it’s blue and sparkling, a mirror-image of the early-morning mist-free sky.

Far and away beyond the pool the rising sun pours its benevolence over summit snows. Out there, a distance of maybe 10 days’ walk away, I see a vertical arctic wall shrugging the clouds – shapely, iridescent, unbelievably beautiful as its colours change with each succeeding moment.

The impact it has on me is instantaneous.

‘Will you take a look at that!’ I gasp at Max as I grab a fleece with one hand, boots with the other and lunge out of the tent in uncontrollable, child-like excitement, then part-stumble, part-hop my way up the slope on the right, where last night there’d been fireflies, but which this morning is diamond-studded with dew.

On gaining the top of the hill I run out of breath. Not with altitude, for we’ve not yet reached even 3000 metres, nor from my haste in getting here, but because all the world below to the east and northeast slumbers in ignorance of the new day beneath a gently pulsating cloud-sea. On it floats the sun. And a black-shadowed, whale-back ridge that can only be the Singalila bordering Sikkim. My eyes, a little moist (from the crisp morning air, you understand), travel along that ridge which rises steadily above the clouds until it gathers snow and what can only be hanging glaciers. There, at the far northernmost limit of the ridge, stands a vast block of ice and snow, a wall so colossal in scale that individual features can be identified even from this great distance. Although until now I’ve seen it only in photographs, that great bulk is unmistakable – Kangchenjunga, the world’s third-highest mountain.

In response to that view a bird sings a seesaw refrain from its perch on a shrub nearby. Another joins in. Then another.

I’m inexpressibly happy, jubilant with the glory that unfolds, for stained as it is by the morning light, and gathered on the horizon in an all-embracing glance, Kangchenjunga personifies the lure of high places that haunts my dreams by night and day.

The Himalaya at last! It has taken me 30 years to get here.

Nine months ago I’d been enthusing about the appeal of trekking to a group of prospective customers for Sherpa Expeditions in London. In a large room over a pub in Earls Court I’d shown slides taken when wandering with Berber muleteers in the High Atlas Mountains of Morocco, of tackling the classic high route across Corsica, the romantic wild country of the Pyrenees, and some long treks in the Alps. Since taking the plunge as a freelance travel writer just three years before, I’d been supplementing my income with lectures and presentations at promotional events devoted to mountain travel. On this occasion the audience had been especially receptive, and after the last slide had faded from the screen I’d been bombarded with questions. Some members of the audience were inveterate trekkers, while others had yet to take their first steps, but all were united by a love of wild places and a taste for adventure. Dreamers all, I fed those dreams, then explained how to translate them into reality.

When the last of the audience had finally drifted home to dream and plan anew, director Frank McCready gathered spare sheets of promotional material while I dismantled the projection equipment. ‘How is it you’ve never done a long-haul trip for us?’ he asked.

‘You’ve never invited me.’

‘Would you?’

‘Of course. Somewhere in mind?’ I was winding the projection cable, looping it over the gap between thumb and forefinger, down to elbow and back again, but slowed the process as I waited for Frank to answer.

He passed me a copy of the latest brochure, which I took with my one free hand. It was open at the Himalaya section. ‘You’ve never been to Nepal, have you? Fancy going?’

Would I fancy going to Nepal! What kind of question was that? My heartbeat quickened and I was aware of the pulse in my neck as I attempted to answer without choking on the words. ‘Sure,’ was all I could manage. ‘Why not?’

‘The far northeast of the country was out of bounds until recently,’ he explained. ‘The Nepalese government has just lifted restrictions, and for the first time a limited number of trekkers will be able to approach Kangchenjunga. We hope to send a group in the autumn – we’ve just managed to get it in the brochure. It’s new, and I’m sure it would be a good route to try. We’d need someone to write about it. What d’you think?’

On the tube to Victoria it was impossible to clear the smile from my face. Others sharing the carriage must have thought me mad. I was. But my head was spinning with the prospect of going to the Himalaya at last. For 30 years I’d been climbing and trekking in a variety of mountain regions, but never the Himalaya. I’d read the books, seen the films, attended lectures – how many times had I sat in an audience enthralled by the tales of a top climber describing the ascent of some Himalayan giant, and imagined myself there! Not climbing – no, I’d lost that fantasy long ago – but trekking across the foothills, through the valleys and over high passes. That would suit my needs; just being there among those fabled mountains. Sharing promotional events with trek leaders experienced in Nepal, Bhutan, Sikkim, Tibet, Pakistan, I’d bombard them with questions, envying their travels. I’d led groups in other places, organised numerous trips to ranges elsewhere, but somehow a Himalayan opportunity had never arisen.

Maybe that omission was my own fault, that I’d never created an opportunity for myself, although friends and acquaintances with conventional jobs and a real income had managed it. Some had sent postcards and letters from exotic locations, while I’d simply drifted from one financial crisis to another and contented myself with mountains nearer home, mountains whose familiarity had become part of my workaday world. They were no second best, of that I was certain. But if you love mountains, the Himalaya will inevitably invade your thoughts and stir ambition. To me, the Himalaya had formed a major part of my dream world, while in reality those great iconic peaks remained far off, remote, aloof and unattainable. Until now.

I couldn’t wait to get home to share the news. But by then it was past midnight and the family was asleep.

In the far northeast of Nepal, and straddling the border with Sikkim, Kangchenjunga is a huge massif with extensive ridges and numerous spurs. With five main summits and as many glaciers, it’s considered a sacred mountain by those who live in its shadow. When the first ascent was made by a British expedition in 1955, George Band and Joe Brown honoured the beliefs of the Sikkimese people by stopping just short of the actual summit. The untrodden crown thus remained the domain of the gods, undisturbed by mere mortals. Until 1980, that is, when a Japanese team trod all over it.

Unlike many other Himalayan giants that remain blocked from distant view by intervening peaks and ridges, Kanch is clearly visible 70 kilometres away from the ridge-top town of Darjeeling, where it has become one of the sights of the eastern Himalaya. Over the years I’d met a number of men and women who’d spent time in India during the days of the British Raj, whose eyes would glaze over as they reminisced about watching the sun rise or set on that distant peak while on temporary leave from summer’s oppressive heat in Calcutta. If the sight of Kangchenjunga from Darjeeling could so enthral, inspire and mesmerise non-mountain folk, I wondered what would its effect be on those of us with a passion for high places who planned to trek to its base?

In the seemingly endless months between that initial invitation in Earls Court and the date of departure for Kathmandu, I absorbed as much information as I could about Nepal in general and the approach to Kanch in particular. Truth to tell, there wasn’t much written about the Nepalese approach, for nearly all expeditions to tackle the mountain since the first attempt in 1905 had begun their walk-in from Darjeeling, and had only entered Nepalese territory by crossing the Singalila Ridge near the head of the Yalung Valley, which drains the mountain’s southern flank. On the one hand that paucity of information was frustrating. On the other, the sense of mystery it inspired only served to deepen its appeal.

Then I recalled Joe Tasker’s Savage Arena, a book I’d reviewed for a magazine when it was published in 1982 at the time of the author’s disappearance with Peter Boardman on Everest’s Northeast Ridge. In it Joe had recounted his part in the four-man expedition to climb Kanch’s Northwest Face three years earlier. Taking it from my shelf I leafed through the book and found teasing references to walking along the crest of a ridge between the valleys of the Arun and Tamur, of rhododendrons and clusters of huts, and of porters dwarfed by monstrous loads as they made their way from village to village. Only once did he mention catching sight of the mountain he’d come to climb, ‘hovering white and unobtrusive in the distance so I thought it was a cloud’.

By contrast, Boardman’s story of the same climb, which appeared in his Sacred Summits, offered more descriptions than Joe’s of the approach from the then road-head at Dharan, and brought to mind something he’d told a mutual friend when he’d arrived home from the mountain. It was, he’d said, the most beautiful walk he’d ever made. Considering his vast experience on several continents, that was quite a claim, and it excited my imagination more than anything. Could I be embarked on the most beautiful walk in the world?

Max joins me on the hill overlooking the cloud-sea. He’s brought my camera as well as his own. ‘Here,’ he says with his distinctive Belfast accent. ‘I figured a new boy like you might like to take a few snaps of your first sight of the Himalaya.’

A 30-year-old bachelor with a high level of disposable income, my tent-mate comes trekking in the Himalaya twice each year and enjoys teasing me for being what he calls ‘a new boy’. Mind you, he’s never seen the Alps or Pyrenees, or any other European range for that matter, but in common with many other trekkers in Nepal, his only mountain experience has been here, among the highest of them all. How times change! Until very recently it was usual to serve an apprenticeship among the hills and fells of Britain before graduating to the Alps in order to build experience to face bigger, more remote challenges in the Himalaya. It was a natural progression, and if not exactly a law carved in stone, it was something to which most of us conformed. But the advent of adventure travel and cheap international flights has changed all that, and a trek in Nepal, Ladakh or Pakistan is now seen as a viable alternative to a fortnight on the Costa del Sol.

‘Thanks,’ I say as I take the camera from him and try to capture the essence of this moment in time. Through the lens I scan pillows of mist that froth and foam and lap like a tide against the Singalila Ridge, sharply outlined like a cardboard cut-out. I note the light which floods almost horizontally across the sea of mist, painting a skyline of mountains and pushing blue shadows westward.

We breakfast in a bhatti, a simple teahouse in the tiny village just up the slope from our tents. Mingma and his team have taken over the building next door for their kitchen, and ferry the food to us. There’s porridge, fried eggs and slices of luke-warm toast to spread with peanut butter, honey or over-sweet Druk jam imported from Bhutan. And there’s as much tea, coffee or hot chocolate as we can drink. As I eat, I can see through a hole in the wall to where a pig stands knee-deep in a trough snuffling his own breakfast, while at the same time peeing into it. ‘Adds to the flavour,’ says Bart, our leader. ‘But don’t try it on my breakfast.’

It’s good to be trekking with Bart Jordans once more. Last year we’d been in the Alps together, and I’m delighted to see that his enthusiasm for mountains is as infectious as ever. Only a few days ago this tall, effervescent Dutchman with a halo of dark hair and wire-rimmed John Lennon glasses had arrived back in Kathmandu from leading a trek to Everest Base Camp, and had barely enough time for a shower before heading east to Kangchenjunga with our group. He must have slept well on the 26 hour bus ride, for since we began trekking he’s been bursting with vigour that energises the rest of us.

While we eat the Sherpas collapse the tents, and our porters make up their loads and head off along the trail with small jerky steps, their towering bundles or bamboo dokos held only by hessian tumplines round their foreheads. How do they do it? These guys are only slightly built, with thin legs and either plastic flip-flops or nothing at all on their bare feet. They give no indication of having either strength or stamina – but what must their neck and leg muscles be like?

Leaving the village, our trail slants across open country with an uninterrupted view of the Himalaya ahead. There’s Kanch again, demanding our attention, but as we turn a little to the northwest, we can see across the depths of the Arun Valley to Makalu, Lhotse Shar and an insignificant peak that someone says is Everest. Really? I find that hard to believe, but what do I know? Best of all is a mountain standing south of the main Himalayan watershed, with an extensive, flat-looking ridge supported by a vast wall of snow, ice and rock. It’s Chamlang, a 7000 metre giant first climbed 27 years ago. Bart speculates that we should have had this panorama yesterday, had it not been for the mist. I’m just thankful we have it now.

Our trek takes us over short-cropped grassland that in the Alps would be grazed by bell-ringing cattle; the only livestock we see here are a few goats. We enter groves of rhododendron trees tall as an English oak. Between lumps of moss cladding, the pinkish bark has a rich sheen as though it’s been varnished; ferns and exotic tree orchids adorn some of the trunks, tattered ropes of lichen hang from the branches, and dried leaves form a carpet beneath our boots. At the edge of one of these little woodlands the stumps of recently cut trees tell of nearby houses, and as we pass by women are sweeping the dust from their doorways. Grubby-faced children emerge with hands pressed together in the attitude of prayer: ‘Namaste,’ they cry; ‘I salute the god within you.’ It becomes a mantra, the soundtrack of our journey, as much a part of the Nepalese trekking experience as bed-tea and distant views.

For an hour or so I walk alone, senses alert to every new experience. This is what I’ve dreamed of for so long; I want to miss nothing. There are riches to be harvested wherever I turn; I’m greedy for life.

Suddenly I’m aware of a young voice singing. Delivered in a strong but high-pitched key, the sound is approaching fast, and when I turn I see our 15-year-old porter we’ve named Speedy come tripping along the trail under his 20 kilo load. Neither the weight of his doko, nor the speed of his footwork, appears to have any impact on his singing. I’m impressed. There’s no room for him to pass just here, so I continue until there’s a broadening of the trail where the shrubbery is not so dense. There I stand back, but Speedy decides to stop too, leans his doko against a convenient rock, adjusts the namlo on his sweating forehead, and gives me a wide grin. His song has ended, but I figure it would be good to have it on tape as a record of the journey, so pull my hand-sized recorder from my pocket and give him a demonstration. He speaks, and I play his voice back to him. Eyes wide with wonder, he takes the tape recorder from me to examine. ‘Ramro,’ he says. I sing a few phrases, play them back and point to him. ‘Will you sing for me?’

He understands my request and willingly gives a rendition of the song he’d been singing only moments before. Then we resume our journey together. But the young lad soon draws ahead, singing a different song this time, his plastic flip-flops slapping a rhythm of their own on the bare-earth trail, while I jog behind trying to record more of this very special soundscape.

Together we make rapid progress along the trail, which now slopes downhill before easing along a more open flank of the Milke Danda. A broad valley lies far below the ridge – the same valley that was drowned by the cloud-sea at dawn. Now I see it is patched with trees and small villages, and on its far side hillsides are cleft with streams draining the Singalila Ridge where cloud-shadows ripple their own journeys.

After less than three hours of walking we return to the crest to gain a view onto a dip in the ridge where two lines of simple houses face one another across a paved street. To the left of the houses there’s another small pond, which gives the village its name – Gupha Pokhari. ‘Pokhari’, Max later explains in his eagerness to educate me, means ‘lake’. Beside the pond I notice the blue tarpaulin that signals our lunch stop. But it’s only 10.30!

A stone-built chautaara stretches along the centre of the village street. Our porters have stopped here; their dokos are leaning on the wall, and their sticks – on which they take the weight of their loads when resting briefly on the trail – are hooked on the baskets. Inside two of the bhattis I recognise familiar faces drinking tea, peering out at nothing in particular as I wander past through a haze of wood smoke, pausing to study shops that display a few packets of biscuits, cigarettes, small bottles of the local Kukri rum and brightly coloured hair ribbons – but little else.

Life in Gupha Pokhari is unhurried. Outside one of the buildings a woman seated at a loom weaves a scarf in the November sunshine. Beside her an older woman with wrinkled face and the faintest hint of grey in her hair spins wool, while next door a young man pedals a sewing machine. On the other side of the chautaara a hen with a brood of yellow velcro chicks scratches the earth between stone slabs as a bare-bummed child toddles from one of the houses, squats in the street and looks in amazement at the arc of pee which comes from his tiny willy. ‘Did I do all that?’ he appears to ask. Rising from sleep a black dog yawns, then turns his head to nip at a flea before slumping back to sleep once more.

I turn my back on the buildings and wander across the meadow to where Mingma and the cook-boys are preparing a meal.

Mingma kneads a round of dough. Indre takes it from him, rolls it into flat discs which he lightly forks, then drops them one by one into a pot of boiling fat, where they rapidly swell to become what our cook calls Tibetan bread. Someone thrusts a mug of hot fruit juice at me as I slide my daypack to the ground. ‘Thanks,’ I say; ‘Dhanyabaad.’

Seated on the blue tarpaulin the group is beginning to gel. Some are discussing the morning’s journey, while others write diaries or read a book. Max fiddles with his camera, polishing the lens with a tissue. He’ll be taking no more long views today, though, for clouds are boiling out of a far valley, and one by one the mountains are being swallowed by them. Yet still the sun beams down upon us.

The group consists of seven men and two women, plus Bart the leader and Dawa the sirdar. And Mingma the cook, seven Sherpas and cook-boys, and 26 porters, half a dozen of whom are female – the bright-eyed Sherpanis who keep very much to themselves. This army of 45 is by far the largest I’ve ever trekked with, but such is the scale of the landscape that it’s easy to wander alone whenever I feel the need – as I do now and then – for I’m eager to absorb as much of this country as I can without distraction.

To ensure no one is lost or left behind, there’s always one Sherpa walking ahead to mark the way with an arrow scratched in the dust or on a convenient rock whenever the trail divides, and there’ll be another at the back to scoop up any stragglers. A third Sherpa, an anxious-looking Tibetan, carries a Tilly lamp and keeps his eye on the porters. He’ll need that lamp tonight.

Along the Milke Danda we trek the afternoon hours, at first making an easy contour of the right-hand slope, then heading onto an obvious saddle, followed by a short climb up the crest to a cluster of prayer flags hanging limply from bamboo wands. ‘Om mani padme hum’ drips from them. Now we descend below the flags on a corrugated clay path that takes us in and out of rhododendron woods, through tiny villages consisting of no more than half a dozen timber-and-bamboo houses, and up once more to a view of a solid-looking wall of cumulus where the Himalaya should be.

Camp is set on a terraced meadow within an arc of woodland. Speedy is already there when we arrive, his doko unpacked, a song on his lips as he gathers dry wood for a fire. An overhanging rock provides shelter for the cook, who has a brew stewing in a kettle. Mugs are passed round, and as evening gathers someone points out that the clouds have gone. Above the trees Kangchenjunga hovers in the flush of alpenglow.

Darkness falls, but some of our porters have not yet arrived, and as we eat our meal by the light of a hurricane lamp, heads turn uphill at the slightest sound in the hope that the missing men are coming. An hour drifts by. Then another. Some of the group go to their tents. A bottle of whisky does the rounds, for it’s cold here at almost 3000 metres, and the sky is studded with stars. Then suddenly a faint glimmer of light is detected in the black pitch of the wooded hill. Voices are heard, and half an hour later the Tibetan porter-guide with long jet-black hair braided in a pigtail arrives with the weary stragglers, for whom it’s been a long day.

I beat the dawn in order to be ready to photograph Kanch as the great mountain emerges from night. Frost has painted the grass around our camp, and blanketed porters congregate wherever fires have been lit. The dawn chorus is loud with coughing, and with throats and nostrils being emptied.

Breakfast over, I’m saddened to discover that Speedy is being paid off, and am unconvinced by Dawa’s explanation that he’s asked to go home, for the expression on his face suggests otherwise. I fear he’s been victimised as an individual who stands out from the crowd. Although the youngest of our porters by far, Speedy has been carrying an adult’s load with surprising ease. What’s more, he almost runs along the trail, singing as he goes. By comparison (and I accept it’s an unfair one to make) the rest of the porters appear weak, lazy and slow. I also wonder whether the fact that I’d been seen recording his songs might have counted against him – a sign of favouritism, perhaps, leading to jealousy? If so, it’s something I regret, so when I’m certain no one is looking, I hand him a clutch of rupee notes, which he secretes inside a fold of his shirt and makes his departure back the way we’d come.

By the time we’re on our way the frost has melted, and sunbeams shaft into the forest to illuminate huge spiders’ webs strung across the trail. Lianas hang almost to the ground, and grotesque tumours of moss lend some of the trees a Disneyesque appearance. All that is needed is a haunting melody to set them dancing. I sense that the forest has eyes. It also has sounds. Birds call to one another and cicadas tune up as we burst out into the eye-squinting splendour of unrestricted sunshine.

Now that we’ve arrived at the end of the Milke Danda’s spur, the hills spill in a convex slope for 2000 metres to the Tamur Khola. For much of the way there’s a vast staircase of terraces on which tiny houses are dwarfed by the immensity of the landscape. Far below a milky blue ribbon twists with no sound of its glacial fury reaching us, while on the far side of the Tamur’s valley, halfway up the opposite slope, the little township of Taplejung can just be detected – once we know where to look, that is. High above it there’s a small airstrip, beside which, according to Pemba, we’ll make camp tomorrow night. He’s happy to direct our gaze. He’s been this way before with a Japanese expedition to climb Kanch’s Southwest Face and is eager to be back.

But what catches and holds my attention is the sight once again of that ragged Himalayan skyline – Jannu, Kangchenjunga, Talung, Kabru and all the other 6000, 7000 and 8000 metre peaks that stretch as far as the eye can see; fairyland castles in the sky, they are, supported by clouds. What was it Joe Tasker had written? ‘In the sky hovering white and unobtrusive in the distance so I thought it was a cloud…’.

I settle beside the trail letting others pass by, and am aware that this bewitching land embraces me in its warmth. Fragrances drawn from the vegetation by the morning sun are intense, yet they are so kaleidoscopic in complexity that I fail to separate them into individual scents. Instead I have to content myself with their overall effect. Sounds, too, are beyond my frail ability to recognise and define them. Exotic birds with fanciful plumage swoop from tree to bush and back up to tree again, there to warble their morning anthems while the piercing electric cadence of a million unseen cicadas builds to a deafening pitch.

Before coming to Nepal I had imagined the drama of the great peaks. To me, trekking would mean a visual feast of glacier and rock face, of marching breathless through avenues of soaring mountains, of plodding through crisp snow en route to a lofty pass, there to gaze on scenes of untamed grandeur. I’d given little consideration to the foothill country. Yet this too, I’ve discovered, is a wonderland, and although the snowbound horizon has its seductive allure, I’m in no hurry to reach it. Each step of the approach is full of its own unique brand of magic.

As if to emphasise that fact, all the way down to Dobhan on the banks of the Tamur Khola is a dream. Thatched houses with white and ochre walls stand beside the trail, sweetcorn cobs hang to dry beneath their eaves, garlands of marigolds over doors and glassless windows, pumpkins against a wall…children laughing…voices calling from fields of ripening millet…cocks crowing, goats bleating.

Every terrace has been put to use. On the upper hillside the rice is not yet ready for harvesting, and chuntering streams feed irrigation ditches. Dragonflies hover over them. The sun dances in flooded paddies to flash diamonds as we pass.

The path levels for 20 rare paces. Alongside it a chautaara has been built, some of its stones having been rubbed and polished black by generations of porters who’ve rested here; the upright blocks wear lichens, but the sun-baked path is littered with cigarette butts and orange peel. At the end of the chautaara two young girls and a boy with a dreamy look stand sentry. Silhouetted as they are against castles among clouds, I carry that vision with me.

Further down the slope we pass orange trees and green-skinned grapefruit the size of footballs. Bananas grow beside many of the houses; flame-coloured bougainvillaea and straggly poinsettias hang over the trail; I catch the scent of frangipani.

Here the rice is being harvested by women in scarlet or vivid green saris. Bent double over the waist-high crop, their fingers deftly gather clumps of stalks as a blade flashes the light. The cut rice is then laid over to dry, for water has drained from the terrace and the warm sun will soon draw out any excess moisture. Lower down the slope a bare-footed farmer is ploughing with a pair of water buffalo, turning the soil in pocket-sized terraces, yelping a command each time he reaches the terrace end, where he then hops down to the next tiny field, manhandles the plough and virtually steers the stumbling buffalo to face the opposite direction. He pauses in his work to watch me pass. I raise a hand in acknowledgement. He lets go the plough, and his hands come together. ‘Namaste,’ he calls.

I continue down the trail enriched by his greeting.

There are no certainties in trekking among mountains. Here in the Himalaya I accept that any one of a number of circumstances could affect our plans – sudden snowfall or landslip, ill-health or an inability to acclimatise, the mood of our porters, availability of campsites with water, problems with route-finding… All these things (and others) make it essential to retain a flexible attitude of mind. Although we’ve been given an itinerary, it’s merely a framework within which the trek will manoeuvre a course. We have a date by which we ought to be in Tumlingtar on the River Arun, where a charter flight is due to fly us back to Kathmandu. The rest is open to speculation, and rather than create tensions, it should provide a sense of freedom. That is certainly how I feel, and relaxing by the side of the icy Tamur below Dobhan’s houses while the valley gathers darkness I’m aware of the joy of now and the essence of being. Tomorrow is of no concern until tomorrow arrives.

The river crunches and grinds rocks and boulders that lie in its path. It has its own agenda, its own history. Neither rocks nor boulders will deter its journey to the sea, for with time its ally, and with patience counted in millions of years, the river’s relentless pounding will reduce those blocks of stone into grey powder. Nepal’s greatest export is its mountains, for even as they grow, they’re being worn down and transported via its rivers to the Bay of Bengal, along with countless tons of soil from terraces washed away by the annual monsoon rains.

Our journey has a more limited time scale. It is estimated that we will need 12 days to trek from the road-head to the south side of Kangchenjunga and another two to cross a series of passes into the valley of the Ghunsa Khola, where we will take a day’s rest. Then there will be four or five days to descend back to Dobhan, followed by another four or five trekking up and along the western flank of the Milke Danda to Tumlingtar. But, as I say, this is little more than speculation, a plan written down in a London office. Reality could be very different. Reality is this moment in time, the darkness that has now filled the valley, the rush and crunch of the river, the cool silty sand between my toes, the crackle of the porters’ fires and the rise and fall of laughter. I am aware of the insect chorus among unseen trees – a different sound from that of daylight hours. I see faint lights moving in the village above me, and imagine candles flickering from room to room in medieval homes. I momentarily shiver with the cool air that washes through the valley, riding the snowmelt from high, wild places, and am glad.

The 1600 metre climb from the banks of the Tamur to the Tibetan settlement of Suketar on the ridge of the Surke Danda is a steep and demanding one for porters. It’s a long enough route for us trekkers carrying only daypacks, but for heavily laden men and women it is a gruelling ascent. Bright sunshine, little shade, barely a breeze and the belief that we’d be stopping earlier than we do add nothing but misery to their day, and when they finally arrive at the village long after night has fallen, their mood is sullen. I sense a poisonous blister of resentment held in check only by utter weariness. In the morning that blister must be lanced or it will burst of its own accord.

It bursts.

Breakfast is over, our gear packed and tents collapsed, yet the porters have so far not even begun to sort their loads. Nor do they give any impression of doing so. Bart is deep in discussion with Dawa by the side of the white-painted Buddhist gompa which overlooks our dismantled camp. Strings of brightly coloured prayer flags dance in the morning breeze to match the incongruous sight of a windsock nearby. Just behind the bhatti, where we’d sat for hours last night awaiting the arrival of our tents, a barbed-wire fence deters animals from straying onto a flattish meadow that serves as the airstrip for Taplejung, the township halfway down the slope towards Dobhan. By that fence groups of disgruntled porters sit hunched in circles. At a distance of a hundred paces it is clear that serious negotiations must begin soon or tempers will erupt.

Dawa walks nervously to them. Other Sherpas watch from a discreet distance, as do we. Max voices general concern: ‘The next few minutes will determine whether our trek continues or not. If Dawa buggers this up, we’re doomed to spend the next three weeks sitting here!’

Bart explains that last night there’d been an angry dispute between some of the porters and Dawa. They, the porters, claimed they’d been led to believe we were camping at Taplejung, not here at Suketar. (We’d taken an early lunch at Taplejung, but no porters had arrived by the time we’d set off again; and that should have been a warning.) Now Dawa is going to assert his authority and pay off four of the most troublesome men – and that will not be easy. Neither will it be easy to calm the mood of fizzing discontent.

Dawa Sherpa treads eggshells.

An eruption of angry voices breaks out. Thin men leap to their feet, all shouting, arms waving. Dawa steps back a pace or two, but is quickly surrounded. ‘I’d better go,’ says Bart, who hurries to the fray, followed by Pemba and Dendi.

The noise continues for several minutes, but although there’s a certain amount of pushing and shoving, there is no meaningful physical violence, yet it takes the joint diplomacy of Bart and Dawa to calm the situation. Eventually loud voices subside and spaces appear where moments before there’d been a tight mass of volcanic tension. Dawa’s face appears above the crowd and beckons to Mingma, who hurries to his sirdar’s side. A few words are exchanged, and Mingma goes off to find Dawa’s rucksack in which he keeps a fat wallet of rupee notes.

A few minutes later the blister has been doctored and the tension evaporates.

‘What you English would call a true compromise,’ explains Bart in obvious relief. ‘The porters demanded double pay for yesterday’s climb. It was a bit tough for them, I’ll admit, but Dawa’s got them to agree to one and a half day’s wages. That’s pretty fair, I’d say. Mind you, if we have any more days like that, it could prove to be a costly trek.’

Porters gather their loads. Some are even laughing, while those who were paid off count their wages and set off down the hillside without a backward glance. ‘The trek resumes,’ cries Max, like a wagon-master eager to be on his way. ‘Let’s go!’

Our route across the Surke Danda is more complex than the one had been along the Milke Danda, as we descend to cross streams and rivers and climb through one village after another. For hours at a stretch we are denied mountain views, but this is of no concern, for these Middle Hills, whose summits approach 4000 metres, are rich in visual contrasts, rewarding in vegetation, and lively with wildlife. White-faced monkeys bounce among the forest trees, highly coloured birds swoop across the trail, and I see my first butterflies of the Himalaya – as big as sparrows, they seem to my wide-eyed gaze.

Day after day the trail works its route through an ever-changing landscape, and my eyes are everywhere, for I’m innocent as a child and filled with a sense of wonder. In sunshine and shadow I drift without effort – sometimes among trees and shrubs, sometimes on bare and open hillsides. Life makes no more demands than that of placing one foot in front of the other.

Today we stop early. The harvest has been taken, ploughs have turned the soil in endless terraced fields, and that soil is now baking in the full sunshine. This rucked and wrinkled land fills me with delight, and I’m glad that Dawa has chosen this spot for our tents – two to each terrace with an airy outlook as though from a balcony. Max and I are on the second terrace down from the kitchen tent, which suits us both. Our loads having been dumped above us, I climb the terraces and manhandle a couple of kitbags, and with one under each arm foolishly jump down to the small field of baked earth below. Landing awkwardly, my left foot twists beneath me and I crumple to the ground in agony. I feel physically sick as I grip my ankle, convinced it’s broken. Sweat breaks out on my forehead, but I shiver all over.

‘Let me feel.’ The voice is John’s, a member of our group with a cultured voice and an authoritative air. Until now I’ve not found him easy company, but in this emergency he’s calm and efficient, and I recognise that whatever his background he certainly knows his first aid. His hands are gentle but probing, and he announces (with more certainty than I feel) that nothing is broken. But my ankle is swelling like a balloon. Bart calls for two bowls of water, one hot, the other cold, and after carefully removing my sock, my ankle is immersed first in one, then the other repeatedly until the hot water has turned cool. Then more is called for. I’m given pills to help reduce the swelling and ease the pain, and am carried to my tent.

Passing an uncomfortable night, I’m reminded that mountaineer Pete Boardman also damaged an ankle on his way to climb Kangchenjunga 10 years ago, and had then been carried by a relay of porters until he could walk again. Perhaps that should have given me confidence, but I fear my trek is over. ‘Nonsense,’ says Max. ‘You’ll walk. The alternative is to be buried here.’

In the morning my ankle is discoloured with bruising, and I’m given more pills to swallow. John carefully straps the wound in a crepe bandage, but when I ease my foot into the boot, I find I can only tie the lace very loosely. I’m given a stick to use and helped to stand, but as soon as I put any weight on the foot, pain shoots through my body and I feel sick again.

Pemba is now my constant companion as I hobble slowly along the trail, but a rhythm gradually develops and my pace improves, although it’ll be a full week before the swelling starts to subside. On the second day I lose my balance and sprawl face down on the path, twisting the ankle once more. Every part of me throbs with pain. Pemba helps me up, and soon after I’m seated upon a rock with my foot submerged in a clear forest pool at the base of a cascade pouring over a mossy green slab. I’m dashed with spray, and the water is cold enough to make my whole leg ache, but it’s sheer bliss.

Our trek takes us over ridge spurs and down to gorge-like tributaries, which we cross on suspension bridges that sway and shudder beneath us. The route is a helter-skelter, and there’s barely more than a few paces of level ground anywhere along it. Attractive houses cling to impossibly steep hillsides; snow mountains tease above distant hills before hiding again for hours at a time. Passing through the village of Mamankhe we discover a couple of houses with beautifully carved balconies decorated with containers of flowers. But for the thatch on their roofs they could have been transported from the Bernese Oberland. Padding barefoot along the trail nearby, two young children return home beneath towering loads of foliage – presumably fodder for their animals. They stand back to watch us pass, but say nothing. Much later the route takes us through a cardamom plantation, after which we splash through a side stream and make camp below a sad-looking broken village.

Yamphudin is still in shock. A month ago, at the tail-end of the monsoon, the Kabeli Khola burst its banks and swept half the village away. Huge boulders and mud banks remain where no boulders or mud banks belong. Trees have been uprooted, and river-ravaged houses stand among banana groves tilted at odd angles where the land has been uplifted by the force of the water. Villagers stare at us with vacant expressions as though life has been drained from them, but a policeman appears to check our permits, and while the tents are being erected he squats on his hunkers and draws deeply on a cigarette. He tells Dawa there’s an American climber with a broken leg waiting in the village for a helicopter to carry him out. Apparently he fell while crossing the ridge ahead, and since he was too heavy for his porters to carry, he had to crawl all the way down to Yamphudin. I feel the pain in my ankle and make a mental note to take extra care on our crossing tomorrow.

We discover there are two ridges to mount before we finally enter the valley that leads to the south side of Kangchenjunga. The first of these is crossed at the Dhupi Bhanjyang, below which the slope is steep, greasy and crowded with mist-hugging trees, while the second gives way at the Lamite Bhanjyang, where we catch sight of chisel-topped Jannu, Kanch’s most impressive neighbour that was first climbed by a French expedition in 1962. No other snow peaks can be seen, yet we know they are there. In another day or two, perhaps, we will be among them, but first we must descend with care along the edge of two monstrous landslide scars, then through a forest of chir pine, fir and bamboo, and finally among rhododendron trees above the east bank of the river that drains Kangchenjunga’s glaciers and snowfields.

There’s a bird that sings first thing in the morning with a sound like that of a gate in need of oil. But not this morning. The forest is silent. A heavy frost stiffens the tent, and the only sound to be heard is the rumbling of the river. Autumn is in the air, and the last deciduous trees are patched with russet and gold. Leaves drift in lazy spirals as the day slowly warms.

Once we’re on the move we rise along the true right bank of the river, exchanging broad-leaved trees for tall mossy-trunked conifers. On open meadows straggly clumps of berberis blaze scarlet.

Then all of a sudden mountains are just ahead. Well, a day or so’s walk away, but seeming just ahead. White-plastered mountains, they are, with crests etched sharp against a deep blue sky. My heart makes an involuntary leap in my chest, and I realise I’m smiling. This is an alpine world, for although the summits are maybe 4000 metres higher than our part of the valley, I’m unable as yet to grasp the scale of things, and I stumble. A sharp pain shoots through my leg, for my eyes are not on the inconsistencies of the trail. They are focused on peaks unknown.

We take to the broad, stony river bed. The river is only a few paces away. We can hear its thunder and see occasional bursts of spray tossed from midstream boulders, but other than that it’s lost to view. We pick our way towards the mountain wall that blocks the far end of the valley. There is no path to speak of, but our porters are ahead, the prints of their bare feet easy to follow in drifts of glacial sand between the rocks.

In the early afternoon we pull up a rise and come onto the yak pasture of Tseram at a little under 4000 metres. The size of a football pitch, sloping gently towards the river, it’s fringed with scrub and rocks. Rhododendrons bank the lower hillside, while a fuzz of cypress trees grows a little higher. A group of porters build a fire against a huge smoke-blackened boulder that stands on the edge of the pasture. The unmistakable sound of kukri knives hacking at the branches of rhododendron trees rings clear. It is one of the alarming sounds of the Himalaya, and although I hold no knife, the guilt is as much mine as that of our porters.

Other porters arrive, dumping their lozenge-shaped loads of tents and kitbags where they stop. They wipe their brows, look around, and in a glance decide where they’ll build their own fires. Moments later I notice one man sitting alone hacking at something by his feet, the curving blade of his kukri shines as he makes swift cutting movements. I’m intrigued – is he carving something? If so, what? I edge nearer and am horrified to discover he’s trimming his toenails with a blade as long as his forearm. One slip and he’ll be toeless.

On the eastern side of the valley lies a way to Sikkim over the Kang La. Some of the early expeditions used this pass on their approach to Kangchenjunga from Darjeeling. Frank Smythe crossed the Kang La in 1930 with an international expedition led by the German-Swiss geology professor GO Dyhrenfurth, and on arrival here he found a simple yak-herder’s hut. A long building with wide eaves, one end housed the yaks, while the other was reserved for the herder and his family. According to Smythe’s account, the family’s bedding was a mass of dirty straw alive with fleas, and cooking was done on a fire of rhododendron wood on a stone hearth. Our porters are not the first, then, to attack the rhododendron trees of Tseram.

I’m unable to take my eyes off the head of the valley. Up there, Kabru’s lofty ridge sparkles in sunshine. Next to it is shapely Ratong, with the deep saddle of the Ratong La below. Snow and ice smear every verticality, yet the valley walled by those peaks is devoid of glacier or snowfield, so far as I can tell from here, which makes the impact of that white vision the more profound. Then, as the afternoon moves towards dusk, the lowering sun turns an unnamed rock peak a little northeast of here into a glowing tower of bronze. Suddenly Kabru and Ratong lose their dominance. Clouds boil up from the lower valley, and one by one all the mountains take their leave.

One more camp and we’ll be within sight of the Southwest Face of Kangchenjunga. Since leaving Basantpur at the road-head – what was it 10, 11 days ago? – every day has been filled with wonders. The lush foothills and more rugged Middle Hills have rewarded each hour, and if we were to go no further, they would have justified travelling all the way to Nepal. Even so, the prospect of coming within touching distance of those Himalayan giants denies me sleep, and I’m saddened to know that two of our group will wait here while we go on tomorrow. For several days one of our women has been suffering from diarrhoea, and the other says she’s trail-weary and has run out of steam. So near, yet so far…

I cannot believe this day has arrived!

On three sides I’m hemmed in by mountains of exquisite beauty. Behind me the Yalung Valley descends in a series of steps. On each level a baize of autumnal grass hints at pasturing for yaks, although I’ve not seen any this morning. Every once in a while a diaphanous web of mist drifts up from the lower, unseen valley, but by the time it reaches this point it spins, tears and evaporates. The air has a crisp bite, yet shaded from any breeze the sun’s warmth is reminiscent of a late Indian summer. On this dazzling day the light is so acute I’m forced to squint behind dark glasses.

Topping another rise I’m suddenly aware that for the past hour or so I’ve been walking through an ablation valley – off to the right there’s a dark wall of moraine, which conceals from view the great Yalung Glacier, and to the left the pasture stops abruptly at the foot of a mountain. A hanging valley breaks the uniformity of that left-hand slope, but ahead…ahead I see a glacial lake. Shallow and ice-edged, it acts like a shining mirror. In those waters summits of rare perfection have been uprooted. Images of snow-sheathed mountains dazzle the sun; they float and shimmer upside down, while their real selves form a backdrop that until now belonged to a world of dreams.

I lower my rucksack to the ground and position myself on a convenient rock. Alone, my soul floats in a breathless silence.

The poet Robert Service once wrote that silence is man’s confession of his own deafness, and I know he’s right, for it’s not silent here at all. Peaceful, yes. Almost devoid of sound – but not quite. There comes the whisper of a stray breeze, filtering not from the lower valley, but from ahead and across the other side of the unseen glacier where Koktang is a crystal curtain, its immaculately fluted ridge tilting shadows that outline every individual fold and ripple of its face. That breeze brings with it frostnip and the soft hum of distance.

Koktang’s left-hand arête sweeps down to the U-shaped cleft of the Ratong La, through which I see mountains that belong to another country. Those snow peaks of Sikkim seem to be dwarfed by the immediate scene, yet their presence adds to its glory. On the north side of the Ratong La rears the great cone of Ratong that we’d gazed on yesterday from Tseram. This acts as a buttress to the formidable block that is Kabru, whose face is crumpled with hanging glaciers, but from here I am unable to see the continuation of its summit ridge, although I know it leads to Talung and then up to Kangchenjunga itself. Kangchenjunga…just around the corner. Only just around the corner…yet I am content to wait a little longer before setting eyes on its Southwest Face. For this moment in time there’s as much scenic grandeur as I can absorb.

Now I’m aware of a soft tinkling sound, so lightly suggested that it’s necessary to hold my breath. There it goes again – and again – as a stream breaks free of its early glaze of ice and finds release across the pasture.

I’m not certain how long I enjoy the solitude, but eventually the peace is disturbed by a familiar sound when one porter after another comes over the bluff behind me to traipse across the yak-cropped grass. The first announces his presence with a cough, a hawk, and a gob of smoke-induced phlegm. The juggernauts of the Himalaya are on the move again.

Once more we camp early, this time on the uppermost yak pasture known as Ramze, where the successful 1955 Kangchenjunga expedition had their so-called Moraine Camp, and where their 300 porters set down six tons of food and equipment to be ferried up the Yalung Glacier to their base camp. By comparison it is empty today. Just a handful of our blue ridge tents to provide a modicum of shelter for one night only.

At an altitude of more than 4600 metres, the pasture is hemmed in by a curving black wall of moraine just short of the point where the valley makes an abrupt turn to the north. Two herders’ huts stand on a slope behind our tents, and above these Boktoh scratches at the sky. With nightfall the temperature plummets, and when I brave the chill for a pee shortly after midnight everywhere is coated with frost and Boktoh glows in the light of a full moon. I stand entranced by a heaven flushed with stars, each one diamond-sharp and close enough to touch. I’m tempted to pluck two or three from the sky to carry back to the tent to use as candles.

Bed-tea is early in that frost bowl, and we breakfast on porridge long before the sun is awake. Cocooned in down we trudge round the bend of the valley towards the bulk of Kangchenjunga, which gradually appears like an impregnable fortress at its head. An avenue of snow peaks, anonymous still in shadow, draws us on. It’s bitterly cold and too early for words. Day may have dawned high on Kanch, but here in the ablation valley night still holds sway. But before long, across the Yalung Glacier the great crusted ridge of cornices that links Ratong with the many summits of Kabru, and Kabru with Talung, begins to appear translucent. Beyond those mountains the sun is working its magic from a secret Sikkimese meadow where it has spent the night. I sense its rising. Then there’s an explosion of light, a halo appears and ice crystals dance in the still morning air.

Kangchenjunga, to which we have been walking for so many days, now offers its Southwest Face for inspection. Broken here and there by black ribs of rock, it has a formidable presence, its glaze of ice and snow stippled by what appear from this distance to be minor cracks, but which in reality no doubt are monstrous glacial shelves. Almost 4000 metres higher than where I stand, the wall is topped by a crest of ice carved against a sky of deep intensity. A glorious mountain it truly is, but so too are those to the right and left of me, each one no less spell-binding in its beauty than Kanch itself.

Pemba grabs my arm and points up the left-hand slope. ‘Bharal,’ he hisses. These are the so-called blue sheep of the Himalaya, and I stand rooted to the spot to watch as a small herd of the short-horned animals skitters across what looks like a vertical gully. A few stones rattle down. Then peace is restored.

My Sherpa friend is excited to be back in close contact with Kangchenjunga. Today it is his mountain and, full of stories of his time here with the Japanese expedition, he directs my attention to individual features on the massive face. In honour of his return he’s wearing a pair of red quilted trousers from that expedition as a souvenir.

We clamber onto the moraine crest and look down upon the glacier. In the Alps it would either be riven with blue-green crevasses or carpeted with snow. Here in the Himalaya we gaze upon a junkyard bearing the debris of the mountains that wall it; a chaos of rock and rubble – grey, drab and lacking appeal.

Pemba presses on, now joined by Dendi, while I follow close behind, panting with the unaccustomed altitude. I am made breathless not only by the thin air, though, but by the scene ahead, above and behind, for this is the culmination of a dream; the Himalaya at last!

At last we reach a prominent chorten, like a huge milestone on the moraine crest, with an uninterrupted view of Kangchenjunga as a backdrop. A cluster of bamboo wands wearing strips of printed cloth rise from the top of this pile of stones. We stand before it without words as a gust of wind snaps at the flags to disturb the prayers. A flotilla of ‘Om mani padme hums’ is released to the mountain deities. Kangchenjunga, abode of the gods, absorbs them all.

Pemba and Dendi move to the other side of the chorten, where they deposit grains of rice and a few small-denomination rupee notes on a flat stone shelf. In unison they begin to chant their prayers, deep mumbling sounds like the hum of the universe, while broken thumbnails flick prayer beads. I stand to one side, deeply moved.

When they finish, Pemba turns to me and commands: ‘Now you must pray.’

‘Okay,’ I respond. ‘What should I pray?’

‘You pray like we do. That you come back again.’

So I do.