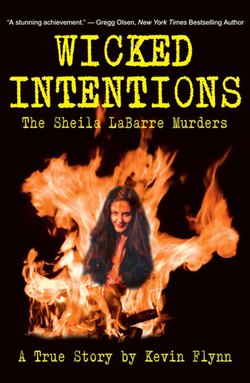

Читать книгу Wicked Intentions - Kevin Flynn - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление6

His First Love

On February 14, 2006, about six weeks before police would scour an Epping farmhouse in search of Kenneth Countie, the young man could be found sitting alone in the barroom of a seaside hotel. It was a ritzy restaurant on Hampton Beach, with staterooms that overlooked the Atlantic Ocean. The orange plastic snow fence was still wrapped around the beach and large patches of white snow lay on the eroding sandbars.

The lounge was moderately filled for Valentine’s Day. The mood was upbeat with a deejay spinning tunes to keep it that way. The manager came to the bartender, Tony Thibeault, with a request.

“Keep an eye on him,” he said pointing to a young man who had wandered in from a very cold night. The man hadn’t requested a table nor asked for something to drink. “I think he’s a transient.”

Thibeault asked the young man what he was doing at the Ashworth. He responded that he was waiting for his girlfriend, so Thibeault told him he could sit at the bar while he waited. The young man said his name was “Kenny.”

Thibeault noticed Kenny had a hard time making conversation and maintaining eye contact. He assumed the kid had some kind of learning disability and checked on him frequently.

An hour passed and no one showed up. Most people who spent that much time alone in the bar—on Valentine’s Day—usually got the hint and left. But Kenny stayed, patiently. He wanted a relationship, thought this could be a turning point in his life.

Thibeault noticed a woman breeze into the barroom and scan the place. She was bleached blonde and stocky, and she wore a denim coat, cut at the hip like an Eisenhower-style jacket. She faced the bar as Kenny came up from behind her and tapped her on the shoulder.

What do you know, the bartender thought. He really did have someone coming for him. But Thibeault didn’t believe the woman was Kenny’s girlfriend. He was quite sure, by the way they looked at each other, that they had never seen each other before that moment. Thibeault wondered if the woman was a call girl.

The couple sat down at the bar, their backs to the picture windows overlooking the street and the beach. She ordered a bourbon on the rocks; he got a soda. It was obvious she controlled the conversation.

The woman hailed the bartender. “The music is too loud. Will you tell the disc jockey to turn it down?”

Thibeault went to Dan Guy, who had been deejaying at the Ashworth for nearly twenty years. Guy was also one of the most sought-after radio engineers in New Hampshire. He could keep his own counsel on the acoustics of the L-shaped room. He knew damn well the music wasn’t too loud and there were still couples trying to dance, but Guy agreed to bring the volume down a bit.

“The music is still too loud,” the woman complained.

“I’m sorry,”Thibeault said, “but that’s as far as the disc jockey wants to go on the volume.”

“That,” she replied, “will be reflected in your tip.”

“I can live with that,” he deadpanned.

The couple chatted some more. Kenny mostly listened, nodded his head in agreement. The woman paid the tab and, true to her word, left Thibeault only two dollars for a tip. They went outside to her car, started the engine, but didn’t drive away.

Back inside, Thibeault and Guy laughed and laughed about Thibeault’s quick comeback. It really wasn’t like him to mouth off to customers, not unless his blood pressure was up. Guy, who, as a morning radio disc jockey, once convinced gullible listeners that a moose on an ice drift was floating down the Merrimack River, liked a good laugh.

The pair noticed that the mismatched couple had gotten in the car but not left the parking space. Watching through the great picture window of the lounge, Thibeault and Guy looked at each other and cracked up some more. They knew the young man and the brash woman were having sex in the black car under the streetlights.

If Kenny had thought this would be a turning point in his life, he was correct. But not one of joy. One of horror and unspeakable pain. A turning point that would soon lead to the end of his life in a manner of evil design and of wicked intention.

Had he left the restaurant five minutes sooner, he might never have met Sheila LaBarre.

By all accounts, Kenny was a sweet, unassuming young man. He grew up with his parents in Tewksbury, Massachusetts, not far from Boston. He graduated from a technical high school as a mason. He was best known for his talents on the ice hockey team and as someone who walked the school wearing his purple team jersey with pride.

Kenny loved many of the things normal boys growing up in New England loved. His family was drawn to the ice. His mother, Carolyn, was a figure skater. Kenneth, Sr. was a youth hockey coach and Kenny picked up both the passion and the skill for the game from him. He loved music and sang with an enthusiasm that surpassed his pitch.

“You can’t wear that hat,” his mother told him of the Yankees ball cap he owned. She knew little about sports, only vaguely aware when she said it that the Red Sox and Yankees were in some kind of death struggle for a championship. “You live in Boston, Kenny. People are going to give you trouble for it.”

“Don’t worry, Ma,” he told her. He knew she worried about him dearly.

That’s because Kenny Countie was not a normal boy growing up in New England. He was never formally diagnosed with a handicap; teachers said he was “a tad slow.” Kids were crueler. They called him “stupid” or “retard.” But he was neither. Kenny had a developmental disability. The experts told his mother his mental capacity was around that of a twelve-year-old.

His mother suspected Kenny might have a form of autism. He had an exuberant smile, but he wasn’t overly affectionate. He had trouble reading others’ social cues.

“Come here and give your mum a hug,” she often said.

“Oh, Ma!” he moaned as she tried to put an arm around him. He wouldn’t cuddle or hug or offer an unsolicited “I love you.”

Years before, Carolyn Countie had gotten into a terrible car accident that left her in a coma. She was left unable to walk or talk, with both a hole in her head and a hole in her throat. Two-year-old Kenny was temporarily left without a mother. Through therapy and sheer will, Carolyn Countie was able to recover and eventually return to her family. When she became pregnant again the doctors were dead set against her carrying to term. They feared for both her life and the life of the child. She’d have none of their protestations. She gave birth to her second son, who was physically and mentally strong. But for years, doubts nagged her about Kenny’s development during her recovery. “Two years old is when a child bonds with his mother,” she said, worried the boy’s reluctance for affection was a result of her car accident.

His mother was the most formidable presence in Kenneth Countie’s life. Carolyn Countie remarried and moved to Billerica, Massachusetts. Gerald Lodge, her new husband, was born in the United Kingdom and moved to the States. After a few years of living together, Carolyn Lodge started speaking with a British accent herself.

Like any parent struggling to let their firstborn go free in the world can attest, Carolyn and Gerald and Kenneth Sr. had ambivalent feelings about Kenny’s desire for independence. Kenny’s special needs had to be addressed, the balance found between holding a hand and gripping it.

“Kenny, you gotta be careful,” Carolyn pleaded with him. “There are crazy people out there who will eat you alive.”

“Mom, don’t worry about me. I can do it.”

“No, honey. You can’t.”

It was Kenny’s idea to join the Army. Carolyn put her foot down, yelled and screamed at her son. But Kenny wouldn’t listen to her.

She invited the recruiter over to her house. “Are you bloody mad?!” she railed at him. “You signed him up for four years? He won’t last a week.”

The man in the green uniform and gold buttons simply said, “I don’t think you know what you’re talking about.”

Kenny shipped off for Basic Combat Training. Carolyn and her husband made the trip to Georgia for Family Day. The separation seemed more like months than weeks to his mother.

Several buses pulled up to the gathered relatives, and dozens of uniformed trainees poured out. They all looked the same in their black berets, blue shirts and polished boots. People started darting left and right, seeking a familiar face. Amid the happy chaos, Carolyn Lodge could not find her son and began to panic. She tapped the first solider who walked her way.

“Do you know Kenneth Countie?” she asked.

“Yeah.”

“Do you know where he is?”

The soldier stared back. “Ma. It’s me.”

She was breathless. She peered deep into the eyes of the man standing in front of her. “No, it’s not.”

Kenneth Countie was standing up straight, making eye contact. He had bulked up and his thin face looked fuller. He had a presence that was undeniable. He looks wonderful, his mother thought.

Gerald and Carolyn took Kenny to a restaurant. The young man did something he’d never done before. He reached out and opened the door for his mother. She thought it was some kind of joke.

“Are you going to close it on me?” she pried wryly.

“No, ma’am,” he replied. Then he waited for his mother and stepfather to sit at the table before he took his own seat. Mrs. Lodge realized the Army had made a man out her boy.

Kenny’s graduation from Basic was to be a major family event. Carolyn had paid for in-laws in Great Britain to fly to Georgia and attend. It was only two days before the ceremony when the phone rang in her Massachusetts home.

“Is this Carolyn Countie?”

Responding to the name from her previous marriage, she knew instinctively the call was about Kenny. “What’s wrong?”

The man identified himself as Captain Pasquale, a commander in Kenny’s training unit. “Your son won’t be graduating with the class.” She yelled, pleaded and demanded to know why. The captain refused to say.

With their pre-paid tickets in hand, Carolyn dragged her husband to the airport and flew down to Georgia. They sat in their rental car outside the main gate, watching people come and go. Finally, with the precision of a ranger sniper, Lodge got out of the car and approached a military man walking out of the base.

“You there,” she said. “What’s that decoration on your uniform? What does that signify?”

“That means I’m a captain,” the officer said, referring to his silver bars.

“What’s your name?”

“Captain Pasquale, ma’am.”

Considering there were over 100,000 soldiers, civilian workers and family members who lived and worked at the fort, this was quite a coincidence. “You’re just the bloke I’m looking for.”

The Lodges accompanied Pasquale into the base and found an empty room. “Tell me why my son will not be graduating with his class.”

“In all honesty,” the captain started, “he can run the two miles in full gear. That’s a requirement. He can do all the push-ups. That’s a requirement. But he can’t do the sit-ups.”

“What?” Her son had never excelled academically, but he did well in sports. She was incredulous that the boy couldn’t do seventy-five sit-ups.

“If you want,” Pasquale offered, “come out to the parade field at five o’clock tomorrow when the unit is taking PT. You can see for yourself and decide whether he passes.” The parents looked at each other and agreed they’d show up. “And ma’am, that’s five A.M., not P.M., in case you didn’t know.”

The next morning, with the grass still wet and orange streaks in the sky, Kenny trotted out to the field. He was wearing sneakers, shorts and a gray T-shirt that said “Army.” The first exercise was a run around the track. From a distance, Carolyn Lodge watched her son glide effortlessly. He was nearly done when he slowed down and doubled-back.

What’s wrong? Lodge thought.

Kenny pulled alongside one of his fellow trainees who was lagging. He began clapping and shouting encouragement to him, wishing him forward to the end.

What a wonderful thing my son just did.

After the run, the unit dropped down for push-ups. Again, Kenny had no problem. He looked even stronger than he had at Family Day. Then, the young recruit began his sit-ups and Carolyn Lodge saw the problem right away. Kenny began the sit-up flat on his back, level with the ground.

“No, Kenny. Not like that. You’ll never be able to get up and do a sit-up like that.” An exercise instructor herself, Carolyn Lodge knew the proper technique required going back only part of the way and pulling the torso forward. She watched as her son struggled to pull himself off the ground and make it to his knees, flopping and failing. He’ll never do seventy-five like that.

Later that day, while the rest of his class was graduating, Kenneth Countie was directing traffic on the base. His mother caught a glimpse of him before they left. The shoulders that were once straight sagged. The eyes that met others now avoided contact and searched the ground. The confident smile had disappeared, his chin pinned to his chest.

It looks like he sank one million feet under the ground, she thought.

Everything the Army had done for him seemed to vanish all at once.

Back home in Massachusetts, Kenny attempted to gain as much independence as he could. In January, he moved to Wilmington, Massachusetts, with a friend. It was the first time, aside from the Army, that Kenny Countie lived away from home. He got a job at a car wash. His co-workers liked him because he was pleasant and dedicated to the job. He showed up for work a half-hour early every day. However, his colleagues noticed Kenny had trouble filling out his W-4 and the other paperwork needed on the job.

Carolyn Lodge appeared frequently at the car wash, checking on her son. On the days she didn’t show up there, Kenny came to the health club where she worked. He’d beg her for something sweet to eat. She’d oblige by giving him the candies she carried in her pocketbook in case he asked.

Kenny had a cellular phone, pre-paid by his mother. He called every day, sometimes more than once. “Yes, love. Yes, love.” To some of Carolyn Lodge’s friends the calls seemed excessive, but she was determined to prove her devotion as a mother and nurture him.

Kenny called his little brother, too. Sometimes it irked the teen to get a call from his older brother, asking stupid questions, passing on lame observations. It was hard enough finding his way in high school (girls, sports, studies, friends) and being attentive to two sets of parents wanting to know his business. He didn’t want to have to deal with his older brother.

In February 2006, a depressed twenty-four-year-old Kenneth Countie attempted suicide. For all the talking he did on the phone, he didn’t share many of his inner demons. The thought of losing her oldest son unnerved Lodge. She pledged to redouble her efforts to watch over Kenny.

The young man had a hard time meeting women. He wasn’t the most confident and approaching a woman face-to-face seemed frightening. He rang up a dating service and got a voice mailbox. After punching a few numbers to set up his profile (“Press one if you are playful; press two if you are shy…”), he recorded a message about himself and listened to the other postings. He exchanged voicemails with a woman with a Southern accent. She liked the sound of his voice. It reminded her of someone. Dinner on the seacoast was her idea. She would pay.

Four days later, Kenny’s roommate, Eric, was awakened by a truck that pulled up in his driveway and tooted the horn. He heard his roommate banging around in the other room, so he knew the ride wasn’t there for him.

“Kenny, what’s going on?”

“I’m leaving with Sheila,” he said.

“What the fuck are you talking about?” Eric stammered back, still half asleep.

“I’m going to spend the weekend on her farm in New Hampshire. She has horses and rabbits, and I’m going to help her take care of them.”

“Yeah? When you think you’ll be back?” Outside, the horn honked again.

“Tomorrow. Sunday.” Then Kenny squealed in the little boy voice that reminded his roommate he was mentally deficient. “We’re going to be so happy together!”

Kenny bounded down the stairs, grabbed his overcoat and jumped into the waiting truck. Sheila LaBarre never got out or acknowledged Eric, and after they left he realized Kenny hadn’t packed any personal belongings. His van was still in the driveway.

On Monday, February 20, Carolyn Lodge got a call from her son.

“Yes, love,” she began in Anglican tones.

“Mommy…”

Kenny was crying. Still reeling from the recent suicide attempt, Lodge started to panic. “Kenny! What is it? What’s wrong?”

“Eric’s brother called Sheila a bad name.”

“Who? Susan?”

“No. Sheila.”

Now Lodge was confused. Surely this wasn’t a life-or-death situation, but her son was upset about something. “What do you mean?”

Kenny had not returned to his Wilmington apartment on Sunday as expected. And not on Monday either. His roommate was worried; he and his brother called Kenny’s cell phone. The young man was meeting their inquiries about when he might be home with some indecision. Sheila, sensing the problem, took the phone and started arguing with the men. When Kenny took the phone back, the brothers were calling Sheila a “bitch” and a “cunt” and every other name they could think of.

In between sobs, Lodge was having trouble piecing together most of this. She had no idea from where Kenny was calling. Lodge tried to press her son for more information when she heard Sheila in the background.

“Kenny, give me the phone,” she ordered. From the tone of her voice, it sounded as if she was unaware he’d made a call.

Who are you and what are you doing with my son, was what Lodge wanted to say when a lightning bolt of rage came out of the earpiece of the telephone.

“He is fucking twenty-four years old. Leave him the fuck alone!”

Lodge was stunned. Then indignant. Who was this woman Kenny had gotten himself entangled with?

Sheila went on. “We’re fucking happy!”

“I am Kenny’s mother…,” she began, but heard the cell phone click off. Bloody hell, she thought.

On Tuesday the twenty-first, Kenny was not answering his cell phone. Lodge called the car wash looking for her son. They told her Kenny hadn’t been in to work and they were worried about him. It wasn’t like him not to show up, not to call.

Kenny’s roommate told Kenneth Countie Sr. that this woman had taken him to a farm in New Hampshire. At least now we know where he is, Lodge thought. By Friday, when Kenny still hadn’t called his mother and his van and belongings were still at his apartment, Lodge decided she had waited long enough and decided to call police to report him missing.

Epping Police Sergeant Sean Gallagher took Lodge’s call. The mother explained, very calmly, that her son had been staying on a farm with Sheila LaBarre. She said her son had a mental deficiency and had recently tried to kill himself. Gallagher took the information, promised to touch base with the Wilmington Police Department and said he would go to the farm to check on her son’s well-being.

Gallagher was one of only two sergeants on the Epping Police Department. A Navy reservist for six years, he joined the force in 1995 looking for a career in which he could serve others. Chief Dodge was able to expand the size of his little police force by one more man by taking advantage of a grant from the U.S. Department of Justice. It covered 70 percent of Gallagher’s salary for the first three years of service. The grant dictated that Gallagher’s role would be as a community-oriented patrolman. And though he didn’t walk a beat in pulling on locked doors in urban neighborhoods, he found a way to make the philosophy of community-oriented policing fit with Epping. That meant meeting people, chatting them up, looking ahead to the potential trouble spots. Sheila LaBarre came across his path often, officially and unofficially.

Gallagher didn’t need to do a lot of research before heading out to Sheila’s home. She was a frequent filer, and her case file was filled with minor complaints and petty annoyances. She stormed into the station with letters of complaint—some directed at citizens, some directed at officers. She used her personal fax machine to transmit even more rants to the Epping Police Department after hours.

Some thought the feud (which was mostly one-sided) began after Sheila had been pulled over for speeding and charged with marijuana possession. It took an expensive lawyer and a pound of flesh, but the charge was expunged. Her lawyer urged her to watch out for the Epping cops from then on, advice she took too readily to heart. It was to be a jihad for the indignity they put her through.

Gallagher drove out to the farm later that day with Detective Richard Cote. The department had a standing policy when dealing with Sheila: always go with backup. The policy hadn’t been instituted, because they thought Sheila would become violent with a patrolman; it was put in place after one encounter when “Sheila the Peeler” became inappropriate with an officer. She started to come on to him. The sexual nature of the incident so disturbed Chief Dodge he ordered that none of his men was to approach her alone again.

Gallagher and Cote rolled up past the open wooden gate and exited the police cruiser. The sergeant stood tall and straight in his dark blue uniform and cap, knocking on the front door. A dog barked inside. Someone appeared in the window, eyes through a curtain that looked like a ghost.

“What do you want?” Sheila yelled out the window.

“Is Kenneth Countie here?”

She paused. “He’s here.”

“Sheila, could you come to the door please? So we can talk?”

She refused.

“I need to speak with Kenneth Countie,” Gallagher said patiently.

“Why?”

“He’s been reported as missing. I need to check on his welfare.”

“You can’t speak with him.”

“Why not?”

Sheila stared at the officer, knives in her eyes.

“Sheila, I must speak with him.”

“You can’t.”

“Why not?”

“He’s naked in the bathtub.”

“Well, get him out of the bathtub. I need to see him.”

Sheila moved away from the window and then reappeared.

“I’m going to check with the Wilmington Police to make sure you’re not lying.”

Cote watched as Gallagher stood at the door in the late February air. The farm was silent except for the police car’s running engine. The more he thought about it, the more he didn’t like the situation. Not coming to the door was just par for Sheila. Why wouldn’t she bring him out if he’s truly in there? Is she hiding something? They seemed to be waiting there an awfully long time.

The bolt on the door clicked open. Gallagher’s hand was resting nonchalantly on his holster, his eyes fixed to the widening entrance way. He saw Sheila there, lips pursed. Standing about five feet behind the door, a man wearing only a pair of blue jeans appeared.

“Kenneth Countie?” the cop asked.

“Yes.”

“Are you okay?”

“Yes.” Kenny stood meekly, arms folded in front of him. Cote noticed the kid was thin, but looking at his bare chest and back, could see there were no bruises, marks or other signs of injury on him.

“Your mother’s worried about you. Give her a call right away, won’t you?”

“Okay,” he said.

“Get the fuck off my property, right now!” Sheila said to the police officers, pointing the way back down the darkened dirt road for them.