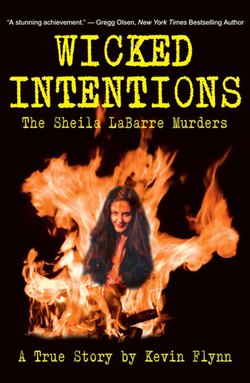

Читать книгу Wicked Intentions - Kevin Flynn - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление9

Wal -Mart

On the evening of Saturday March 11, two weeks before the police investigation of the Silver Leopard Farm began, Sheila turned up at the Wal-Mart customer service desk with Kenneth Countie. Although it lost its holiday season battle with Chief Dodge over twenty-four-hour service, Wal-Mart was still one of the only businesses open late in Epping.

“I need you!” Sheila was rapping her hand on the counter. The younger of the two women behind the desk approached her, but Sheila put up a hand. “No, you,” she said pointing to the older woman. “I need you!”

“Can I help you?” Brigit Pearson asked. She wore the familiar blue Wal-Mart vest with her first name on a tag. Sheila stood in front of her wearing a fashionable brown leather coat.

“There’s a woman, a customer in this store, who just grabbed him by the arm and pushed him out of the way!”

The anger and determination in the customer’s voice at first took Pearson by surprise. She glanced at the young man standing next to the woman. He was wearing blue jeans and a red sweatshirt. Although he would not return the look, keeping his head down the whole time, Pearson could see there was an age difference between the two customers. She looked closer and could see there were cuts and scratches all over the man’s face.

“She did that?” Pearson asked.

“Yes!” Then Sheila said, “Well, no. This is all from a car accident. A really bad car accident and he was burned on his arm and all up in here.”

Sheila grabbed Kenny’s arm and spun him around. The young man made no attempt to resist. Sheila grabbed his sweatshirt and pulled it up over his head, revealing a large burn on Kenny’s back. Pearson was both shocked and embarrassed, but she noted that there was no blood on the inside of the sweatshirt. Pearson noticed something else while looking at his bare torso: his skin color was odd.

The customer service desk was in the center portion of the enormous store, right in front of the checkout lines. Shoppers passing by started to stare. Kenny did not look up. Pearson wasn’t sure whose gaze he was avoiding: hers or Sheila’s.

“He’s in a lot of pain,” Sheila continued. “I want something done right now! I want the head of security and the manager here now! Do you hear me?”

I’ve got to defuse this situation somehow, Pearson thought. Other employees were gathering at the customer service desk or watching from afar.

“I want that woman thrown out! I want something done now! I have friends who work at Wal-Mart, this Wal-Mart, and I want something done now or I’ll have your job!”

Pearson tried to explain that they did not have a security team at their store. “Would you like to call the police?”

“No. I don’t need the police. I’m a lawyer and I can do it myself.”

Pearson dialed the extension for the management office. One of the store’s co-managers, Dan O’Neil, said he’d be right down. Another associate, who had witnessed the tirade, found co-manager Patsy Lynn on the floor.

“There’s a woman flipping out at the service desk,” he told her.

O’Neil and Lynn both approached Sheila with smiles and politely asked how they could help. Sheila’s anger shifted to them as she explained how a woman near the posters in the stationery aisle had assaulted her “husband.” The managers explained they did not have a security team and again offered to call the Epping police.

Sheila tugged on Kenny’s arm and dragged him back through the store. The employees all noticed he winced in pain as she did this. “I’ll have your job! I have friends that work for Wal-Mart in Bentonville. Don’t you hear my Southern accent?!”

Another customer, who had been standing in line at customer service, pulled Lynn aside. “I saw the incident,” he said. “The other woman barely brushed against the man and even said, ‘Excuse me.’ That lady started screaming at the customer in the aisle.”

Minutes later, O’Neil’s walkie-talkie squawked for a co-manager to get over to the electronics department. Sheila was standing in front of a yellow smiley face sign, her own face twisted into a terrible frown. She was yelling that her husband had been assaulted in the store. Again, she pulled on the red sweatshirt and tugged it over Kenny’s head.

“Please don’t do that,” O’Neil requested. “That’s not necessary.”

“You’re all being unprofessional,” Sheila spat. “Don’t you know your own job description?”

“There’s no need to turn this into a personal attack,” he countered.

“I’m going to sue Wal-Mart for millions of dollars! And I’m going to have you all fired!”

“Since you have mentioned suing,” O’Neil said, “we no longer have anything to say to you.” The employees all walked away, hoping this would calm things. Sheila grabbed Kenny and left the store.

A half-hour later, store co-manager Hank Linton was asked to take a call from an angry customer. The associate said the caller specifically said she didn’t want to talk to Dan or Patsy.

After punching up the line, Linton got an earful from a woman who said she had a run-in with two assistant managers and that her husband had been assaulted in the store.

“My husband is home with me and he’s crying, because he is in so much pain from the assault,” she said. The caller then asked about the security cameras positioned around the store. “Do they have audio attached to them?”

“Security is not my job title, and I really can’t answer your questions about it.”

The caller said she was looking up flights online to Bentonville, Arkansas, where Wal-Mart’s home office is located. She said she wanted to present her case directly to the company president.

“I have family that work at the home office,” she said. “I also have a family member that does polygraphs for the FBI. I’m going to call my polygraph person and my husband and I will take one. I want the store managers to take one, too.”

Linton endured much of the rant with professional courtesy. The caller threatened to sue for millions. Then she began asking about Dan O’Neil’s history at the store. The caller was sure she had a confrontation with him at another store over dog biscuits or something. Linton provided the woman with phone numbers to the district manager and to corporate offices. He ended the conversation by wishing the caller “a great night,” although by now he didn’t really mean it.

Within the hour, Linton got a page to dial the service desk extension. The associate said there was a strange woman on the phone asking about the managers and talking in what sounded like a fake Chinese accent.

The arrival of the Epping Wal-Mart Supercenter in January of 2004 had been greeted with the typical mix of feelings: great for the consumer, bad for the competitor. Forcing out the tiny shops and storefronts meant altering the character of the town. But for “The Center of the Universe,” the “Great Crossroads,” the gravitational pull of modern American commerce was too strong to escape.

Jumping off of Route 101 at the junction of Route 125, there were already the universal commercial offerings of fast-food restaurants. There was a coffee and donut shop, as ubiquitous in New England as gourmet coffee is everywhere else. Not long after Wal-Mart went in at the junction, a who’s who of franchise labels sprouted nearby. Within a half-mile, there was also a home improvement store, a deli, a family restaurant, a drug store and a second coffee and donut shop (this one on the opposite side of the road, for the apparent convenience of commuters driving the opposite way).

There were those who saw the construction of the Wal-Mart as the Beginning of the End for their town. A cataclysmic event. They tossed at night, counting their fears like sheep. But others were rocked to sleep by the convenience and the lighting, the crowds and the prices. To them, it made no difference. The character of a town is what one makes of it. It didn’t matter if the clerks and store owners knew their names, asked about their aging parents. They could walk inside with their winter jackets unzipped and go from the nail salon to the portrait place to the fast-food restaurant inside the store. They felt plugged in, not to the local community of delis and hardware stores, but to the national community of shoppers who were browsing from sea to shining sea. They could buy armfuls of stuff and go back to the country homes they took pride in.

Four months after it opened, a cashier and a worker in the tire and lube center got married in the Wal-Mart garden center, with a reception in the break room. The department store finally had become a town square. In the battle for the soul of Epping, Wal-Mart wasn’t the enemy. Like Walt Kelly said, “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

On the evening of Tuesday, March 14, Wal-Mart cashier Jodee Hook was working the register when a customer with blondish hair and a brown leather coat began slamming her groceries down on the belt.

“Hi,” Hook said with as much saccharine enthusiasm as she could muster. “How are you tonight?”

“Fuck this store. The fucking door lady said that I need to fucking put more clothes on.”

The comment didn’t sound like something a Wal-Mart people greeter would say. “I’m very sorry. Is there anything I can do?”

“No. There isn’t a fucking thing you can do! I hate this fucking store!”

Hook quickly scanned the grocery items, not wanting to tangle with the customer.

“My fucking family fucking owns this fucking business!” the woman continued. “So I’m going to fucking sue this fucking place! I’m a fucking multi-millionaire and a fucking lawyer!”

Thinking she could calm the customer down by changing the subject, Hook asked what kind of lawyer the woman was. Then Hook apologized when the customer told her it wasn’t any of her fucking business.

“I’m fucking calling my fucking family up and fucking talking to them about this store and getting all you guys fucking fired! You’re all fucking nosey and fucking rude!”

The cashier scanned the last of the groceries and bagged them. The customer handed Hook a fifty dollar bill, which she proceeded to mark with the counterfeit detector pen.

“You don’t need to fucking check out my fucking money. I’m a fucking multi-millionaire and a fucking lawyer!”

“I’m sorry, but I have to check every customer’s money.” The woman took her change by ripping it out of Hook’s hands, then threw her bags in the carriage.

During her break, Hook asked the door greeter if she had said anything about a customer needing to put more clothes on. The greeter said only that she told one woman it was chilly outside.

Sheila LaBarre returned to the Wal-Mart with Kenneth Countie on Friday, March 17. This time, she was pushing Countie in a store wheelchair. The couple stopped in front of cosmetics and talked to store co-manager Priscilla Burch. Sheila introduced herself, then began telling Burch how management was negligent by not scouring the store for her husband’s attacker.

“I am an attorney-in-fact and a notary. I can sign my own arrest warrant for her,” Sheila said.

“When customers mention being assaulted, we need to contact the police,” the co-manager replied.

“I would have followed this woman to her car to get her license plate number. I own a horse farm and I’m a multi-millionaire. I can shop for designer clothing, but the clothes you sell are good enough for me, because they’re good enough for Sam Walton.”

Burch got a good look at Countie’s face. His skin was wan and peppered with bruises and scrapes in various stages of healing. Sheila asked him several times if he was going to faint.

“My late husband was a medical doctor,” Sheila informed the employee. “And I have a medical background. I can treat his wounds.”

You have got to be kidding me, Burch thought. That guy looks like he belongs in a hospital.

Sheila told Burch that she had paid $700 that day for a professional polygraph and her “husband” had passed it with flying colors.

The manager followed Sheila to the seasonal aisle, where she planned to reconstruct the incident. Sheila pushed Kenny around, paying no mind to the shoppers around them. The man’s head was down, as if in defeat. He didn’t seem concerned in the least which direction she pushed him. At one point, Sheila touched Kenny’s shoulder. The man jumped in pain. Again, Burch offered the customer some corporate phone numbers and excused herself to get back to work.

Sheila continued shopping, grabbing a disposable camera. She pushed Kenny past hardware and into the automotive section. They passed dozens of yellow smiley faces, faces that now seemed joyless. Sheila made a sharp right around a corner. Her eyes quickly scanned the shelves. They were there, just beyond the car jacks and cans of automotive oil. There were two rows of them. One whole row of red for gasoline. A couple in blue, meant for kerosene. Next to them, the five-gallon containers in yellow. Those were for diesel fuel. They cost $11.64 apiece. She took two and piled the yellow plastic jugs on Kenny’s lap in the wheelchair. Then she pushed the broken man and the fuel containers to the checkout aisle. All alongside of them, the malevolent smiley faces peered down like some Lewis Carroll nightmare.

She rolled Kenny with the containers in his arms. Her plan for them was lodged in her own wicked mind.

Burch was paged to electronics. When the manager got there, she saw Sheila taking pictures of the security camera domes mounted in the ceilings.

“Is everything okay?” she asked as nicely as she could.

Sheila gave her a look, like an animal regarding a flea. “Yes,” she said rudely and walked away.

At 8:45 P.M., the report came over the Epping police radio for a suspicious person at Wal-Mart, and Detective Richard Cote got the call. Cops in other towns were cracking heads with St. Patrick’s Day revelers stumbling out of bars. It seemed it wouldn’t be a night patrolling Epping if the cops didn’t have to stop by Wal-Mart for something.

Burch flagged down Cote when he arrived at the store. The officer asked what the story was and the manager explained what had been going on.

“Do you have a name?” Cote asked.

“Sheila LaBarre.”

Cote’s reaction was immediate and evincive. Cote was both a football coach and the head of the department’s police union, so he wasn’t afraid of getting into a tumble. But he was smart enough to not approach “Sheila the Peeler” without at least one other officer with him. This call was going to require backup. He radioed for Sergeant Sean Gallagher to meet him at the store.

On February 26, two days after Gallagher and Cote had knocked on the farmhouse door looking for Kenny, Sheila made three phone calls to the chief ’s office within a few minutes of each other. She was in a lather about the well-being check and threatened to sue if the cops came back to her home for the same purpose. She also requested a copy of the National Crime Information Center report that listed Countie as a missing person.

“This woman has a history with the Epping Police Department,” Cote told Burch. “We need to be careful about how we handle things.”

Gallagher entered the store and met Burch and Cote at the customer service desk. He asked Burch how she wanted to proceed and she said she wanted Sheila removed from the store and told not to return.

Sheila’s eyes were drawn tight and beady when she saw the two officers approaching her. She and Kenny were in the frozen food section, and Sheila was using a disposable camera to take snapshots of the security cameras. The sergeant explained that management wanted her out of the store.

“Can I pay for my merchandise first?” The cops looked over at the Wal-Mart employees, who nodded that it would be okay.

While Gallagher talked to Sheila, Detective Cote tried to get a private word in with Kenny. The kid was wearing a goofy kind of top hat and a fur jacket that seemed too big for him. It had been only a few weeks since the well-being check at the farm, but he was taken back by how badly Kenny had deteriorated.

“Are you all right?” he asked Countie.

Sheila LaBarre, who seemed to have a wicked radar about such things, turned away from Gallagher and yelled at Countie before the wheelchair-bound man could speak.

“Don’t fucking answer that question!” she exploded. “You don’t have to answer any fucking question they ask you.”

Kenny dropped his head. He said nothing.

Sheila pushed the non-responsive Kenny toward the self-checkout kiosk. She scanned a box of crackers and some other things, then stuffed them in a blue plastic bag. She had two yellow plastic fuel cans that she didn’t scan, so the associates asked her about them. In a huff, Sheila produced a receipt for the diesel cans and the disposable camera that she had paid for earlier that evening.

Kenneth Countie tried to get out of the wheelchair, but he strained, moving gingerly. Sheila grabbed hold of him and pulled him out. The man had been hunched over in the chair and looked like he couldn’t lift himself. The store managers, seeing the injured man attempting to steady himself with the shopping cart, offered to let Sheila take the wheelchair out to the parking lot.

“No,” she said coolly. “You have harassed me enough. I’m all set.”

Gallagher took a good look at the man stumbling along next to the cart. It is him. It is Countie, he thought. But Countie looked nothing like he did on February 24, standing in the farmhouse door. His skin color was ashen. He had cuts on his face. He had cuts on his hands, and one of them appeared to be swollen.

“Are you all right?” Gallagher asked Kenny as he got into Sheila’s car. Kenny did not have a chance to respond as the woman he had fallen in love with shut the door on them. Gallagher stood there outside the passenger door, but Kenny never looked up, never looked out the window. Sheila drove out of the parking lot and the two of them went north toward the farm.

Later that night, Gallagher filled out the report for police call number 06-1468. He wrote how he told Sheila not to return to the store. “Sheila was removed from the store without incident,” the report’s narrative said. Nothing was said in reference to any concern about Kenny or how he looked.

Kenneth Countie was never seen in public again.