Читать книгу Jacobs Beach: The Mob, the Garden and the Golden Age of Boxing - Kevin Mitchell J. - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 3

Never Far from Broadway

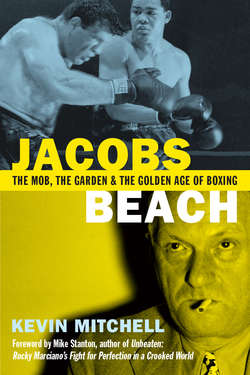

ОглавлениеThere never was a fight promoter more suited to his trade than Mike Jacobs. He started life in gaslit New York City in 1880, one of eleven kids in a family of Jewish immigrants from Dublin, and never took a backward step as long as he lived. Jacobs was born to hustle. His mother and father had stopped off in Ireland when fleeing religious persecution in Eastern Europe, and, after they had joined the Irish rush to the New World, Mike grew up as a cultural oddity in the Hibernian ghettos of the Lower West Side. He was resourceful, unsentimental, and hungry. He sold candy on the boats that went to Coney Island and, from the age of twelve, he scalped tickets outside the second Madison Square Garden. Fans looking for admission to a fight at the last minute any time in the 1890s would find the skinny kid with the loud mouth striking the hardest bargain. He was ruthless in his negotiations. Young Mike could turn a $2 ticket into a $10 profit in the twinkling of his Irish-Jewish eye. There wasn't a better Fagin on the streets of the city. “After sixteen, I was never broke again,” he said once.

Jacobs was so good a salesman that, in a lifetime of aggravation and conflict, he was always confident of a result. Win or lose, his demeanor did not change much. He rose to the top of boxing's dung heap as if by divine edict, and those who looked to outsmart him could not penetrate an exterior born of adversity and forged in greed. Jacobs died a rich if unsmiling man. While it was a love of money rather than the sport that drove him, nobody questioned his right to be there. He was one of the army of foot soldiers who made boxing tick, if not always after the fashion of a tea party.

In an evocative piece written in 1950, Budd Schulberg described him as the “Machiavelli on Eighth Avenue.” Other sportswriters called him “Monopoly Mike.” Dan Parker, the most perceptive and hard-hitting of fifties fight writers, named him “Uncle Wolf.” Jimmy Cannon said Jacobs was “the stingiest man in the world.” Real enemies, of which there were a few, called him far worse than any of this. He didn't give a damn.

Schulberg saw some good in him. “He staged 61 championship bouts, promoted 3,000 boxing shows, signed 5,000 boxers, grossed over $10 million with Joe Louis alone, staged approximately 70 percent of all the bouts below the heavyweight division that grossed over $100,000 (totaling $3 million, with a mass attendance of half a million), attracted in a single year (to 34 Garden shows) nearly half a million people, grossed in that same year $5.5 million, and sold tickets over a 15-year period to more than five million people who pushed at least $20 million through Mike's ticket windows.”

In boxing, it's all about the numbers. Mike Jacobs, who had the heart of an accountant, was the number-one Numbers Man, and the Garden was his bank.

The New York that fashioned Jacobs was different from the skyscraper island of glamour we know today. The stench of poverty and sickness haunted Manhattan's poorest, as it had done since the birth of the colony. But every New Yorker, rich and poor, was mesmerized by the bright lights of Broadway.

The thread that links all life in Manhattan was known in the early days of Dutch settlement as Heere Straat, or High Street. Before that it was an established Indian trail called Wickquasgeck Road, running along a prominent ridge of the hilly island. The name Broadway, according to most educated guesses, comes from Broad Wagon Way, and that sounds right.

Boxing and Broadway started their love affair at its lower reaches.

P. T. Barnum, a man who advertised his wares with all the subtlety and charm of a hooker, knew how to “get them in.” He was the original American con man of sports, and he set the tone for the chaos that followed him. From the moment P. T. opened the doors to “Barnum's Monster Classical and Geological Hippodrome” on the site of an abandoned passenger depot of the New York and Harlem Railroad, at 26th and Madison, on April 27, 1874, he embraced the philosophy that became not only his mantra but the guiding principle of the fight game: “There's a sucker born every minute.”

At the roofless Hippodrome—which Harper's Weekly described at the time as “grimy, drafty, combustible”—the sky was the limit as far as harmless nonsense went. There were waltzing elephants, fire-eaters, the usual sideshow freaks, and all manner of proto-Roman excesses, such as chariot races. And fights, many of which were on the level. Looking over proceedings was an eighteen-foot gilded copper statue of Diana, the goddess of love, who, despite her bulk, swiveled in a light breeze, almost tempting God to knock her down in retribution for the sins committed beneath her ample charms. New Yorkers loved the gaudy excess of P. T.'s Hippodrome, but, even then, the foundations and external trappings were shifting.

Before it became properly notorious, the old place had a couple of different names on its way to becoming known generally as Madison Square Garden, in 1879, just a year before Mike Jacobs was born. And here it was that John L. Sullivan created part of his legend. On July 17, 1882, he took on the British fighter Joe Collins, who was known in some quarters as Joe “Tug” Wilson. Collins/Wilson took up Sullivan's challenge to remain standing for four rounds to collect $1,000. Collins, whose ring history was sketchy and who went down twenty-four times in his efforts to avoid a clean knockout, collected on the dare—but Sullivan's aura was not diminished, at least not among the gullible. They couldn't get enough of this illegal pugilism and the blarney Sullivan brought with it.

The great man's second exhibition, a year later, didn't go so well. Police captain Alexander Williams told reporters he was bringing the entertainment to a halt “just short of murder.” The following year, Sullivan was arrested at the Garden during his bout with Al Greenfield and charged with behaving “in a cruel and inhuman manner and corrupting public morals.” As with P. T. Barnum's credo, this was a statement begging to be added to boxing's unwritten constitution.

John L. was king. And, for much of the time, he was on the run from the authorities, like many of his fans. When prizefights couldn't be snuck into the Garden under the banner of education, they were held in fields and on barges. Sullivan was acknowledged as the world's bare-knuckle champion by beating a part-time punch-thrower from County Tipperary, Paddy Ryan, in front of an audience that included the James boys, Frank and Jesse, in Gulfport, Mississippi, in February 1882. Back in New York, the Garden's interest in boxing spluttered along intermittently . . . for a while.

That first Garden was knocked down, rebuilt and repackaged, opening on the same site in 1890. And the new darling of the fight fraternity was an Irish Californian, James J. Corbett, whose nom de guerre “Gentleman Jim” owed more to alliteration and the vivid imagination of his publicists than any pedigree polished while mixing in high society. When 10,000 sadists flocked through the doors of Garden II on February 16, 1892, Corbett obliged them by fighting three men in a row, knocking two of them out cold. Eight months later, Jim was champ and John L. was chump, washed up and in the grip of the bottle. Corbett “near murdered” the old man and was the new heavyweight king. Gentleman Jim—in the spirit of brotherly love unique to fighters—staged an exhibition in the Garden for the retirement pot of his vanquished foe.

By the time the teenage Jacobs was making a name for himself as a resourceful ticket mover, the intersection of Broadway and Seventh Avenue, at Times Square, laid claim to being the center of the universe. It was gloriously lit, flashing its temptations twenty-four hours a day. And not many, rich or poor, resisted the temptation to make Broadway and the Garden their preferred place of pleasure.

Opening night at Garden II was special. The vice president of the United States, Levi P. Morton, was among the 12,000 guests who gaped at the temple of vulgarity the eminent architect Stanford White had designed for J. P. Morgan, one of the richest men in America.

“From the principal entrance on Madison Avenue,” writes White's biographer Paul R. Baker, “the first-nighters moved through a long entrance lobby lined with polished yellow Siena marble, merging into the huge and colorful amphitheater. Gold and white terracotta tiles decorated most interior walls. Two tiers of seats rose along the sides, and three tiers of boxes, trimmed in plush maroon, filled the ends of the vast space. Some 10,000 spectators could be seated comfortably in the amphitheater, and there was standing room or, for some events, floor seating for up to 4,000 more. The high roof was spectacularly supported by twenty-eight large columns. At the center of the roof, an enormous skylight could, as if by magic, be rolled aside by machinery. This was done during the opening performance but it occurred so quietly that most spectators were not even aware of the change until they noticed the cool night air. As in ancient arenas, provision was made for flooding the floor for water spectacles. As at the Roman Colosseum, animal stables to be used for the horse shows and circus performances were placed in the basement below. Here was a bit of ancient Rome, transformed, modernized, and brought to the Gilded Age of New York!”

It was no tent.

By the turn of the century, Jacobs's career had gone from street mischief to seriously influential. Although barely out of his teens, he knew most of boxing's big guys, including Tex Rickard, the Texan who'd spent years making and losing fortunes in his gaming houses in the Klondike. They met in Nevada in 1904, where Rickard promoted his first fight, a world title contest between Joe Gans and Battling Nelson.

When Jacobs got home, he met Bat Masterson, who'd left the Wild West behind him and was going to be a bona fide New York character, like his new friend Damon Runyon. This was a historic coming together of larger-than-life boxing folk.

Garden II, meanwhile, was to entertain them all with the most delicious scandal, one that would set the tone of activities there for a century to come.

Stanford White had a house in fashionable Gramercy Park, a wife, a family, and a reputation kept clean by an obsequious media. In reality, as Runyon and his pals knew, White was also a New York dandy of substance, with an insatiable libido. While Garden II was his baby, the creation he coveted most was one Florence Evelyn Nesbit, known to all as Evelyn. As befits the story that ensued with the predictability of a naughty nineties melodrama, Evelyn arrived in New York at fifteen, penniless and with a body and face that would buy her all the trouble she and her suitors could handle. She “modeled”—and won the heart of every man in the city, most notably White and a rival, the cruel and unstable businessman Harry Kendall Thaw.

Against the odds, Thaw won. He married Evelyn and spent his waking hours in a jealous fit. With good reason, it turned out. Thaw put money into a cheap musical at the Garden called Mamzelle Champagne, which opened on a hot June Monday night in 1906. Five rows from the front sat White and Evelyn, not too cleverly clandestine. Thaw arrived late for the show, drunk, a pistol hanging menacingly from his limp fingers. Without ceremony, he went up to White and shot him dead, through the left eye.

Thaw was sent to a state hospital for the criminally insane. In so many respects, the murder of Stanford White echoed with metaphors for the fight game. Professional boxing could not exist in a moral vacuum and, time and again, the air hovering over it in Madison Square Garden would be filled with the smell of foul play.

The Great War came and went, devastating a generation. Doughboys came home looking for thrills, of which there was no shortage in New York. And there were plenty of fine writers on hand to chronicle the action. The New York boxing scene has always been sustained—some would say invented—by a rich cast list of literary scallywags.

Jacobs, while never one for books, made sure to stay in with the fight writers, especially Runyon, whom he liked for reasons that had little to do with the music of his words. Runyon, as Jacobs was well aware, was every bit as sharp as he was, tutored in the ways of the world by his father and always on the lookout for a good business opportunity. Jacobs and Runyon would become the firmest of friends.

There is a story, relayed by the fine old New Yorker Jimmy Breslin, which explains how Runyon forged his worldview. Breslin had it on authority, via Masterson, that Alfred Lee Runyan (the family name's correct spelling) once told his son Damon: “Son, there will come a time when you are out in this world and you will meet a man who says that he can make a jack of hearts spit cider into your ear. Son, even if this man has a brand-new deck of cards wrapped in cellophane, do not bet that man because, if you do, you will have a mighty wet ear.”

This was Runyon's pedigree. All his life, he moved among men, and occasionally women, of a gambling instinct. He was particularly close to Masterson. Bat—or Bartholomew, as his mother would have preferred he be called—was a cardsharp gunman of the mythic West, a referee of dubious prizefights and, when he ran out of all those high-class options, a journalist. As for Alfred Runyan, he was a whiskey-wet hack and born liar, an adventurer of the first order who loved the sound of his tales as much as the substance. His famous son, Damon, worked words for a living to rather more lucrative effect. He was a storyteller who bothered not a lot with such fiddling details as the spelling of his surname (he stuck with Runyon after a newspaper got it wrong in his early days) and would go on to bestow on his part of the twentieth century a narrative of consistent unreliability. In young Runyon's genes were the seeds of romance and fantasy. And among the many myths he left us was one for which we should all be grateful: Manhattan.

All in all, you'd prefer to believe Runyon's stories than not. Masterson—for whom the cards fell kindly through the dexterity of his mind and fingers—knew both father and son and liked both, but he was in awe of Runyon the younger, who aspired to be remembered as America's twentieth-century reincarnation of Mark Twain. Masterson believed what Runyon said: that life was mainly 6-5 against, that the little guy always had it tough.

They were all addicted to aphorisms.

“There are those who argue that everything breaks even in this old dump of a world of ours. I suppose these ginks who argue that way hold that because the rich man gets ice in the summer and the poor man gets it in the winter things are breaking even for both. Maybe so, but I'll swear I can't see it that way.”

Those were the words stuck on a slip of copy paper in Masterson's typewriter when they found him dead at his desk on the evening of Tuesday, October 25, 1921, in the offices of the New York Morning Telegraph.

In all likelihood, Masterson was down at the Pioneer Sporting Club earlier that evening to watch Gene Tunney stop Wolf Larsen in seven. If he were not, Runyon would have had him ringside in any account he wrote. Runyon loved Bat Masterson and everything anarchic and wild he stood for. Years afterward, he would resurrect his friend as Sky Masterson in Guys and Dolls.

Runyon and Masterson are from long ago but, without them, and scores of like-minded characters, the landscape inhabited by those who followed them would have been a rather dull place.

In the fight game, the game of six degrees of separation is a fruitful exercise. Sometimes you don't get to six. It goes like this: Masterson was on hand at several of the major fights of his time, having an intimate association with fighters, managers, and promoters whose legacy ran through the business for much of the twentieth century. The man who'd stood side by side with Wyatt Earp in Dodge City and Tombstone (although he missed the infamous Gunfight at the OK Corral) went on to cement a reputation as one of the Wild West's legendary enforcers.

Runyon, besides sitting at the shoulder of boxing's premier entrepreneurs, such as Rickard and Kearns, not to mention all the great and mediocre fighters of his day, helped create the cartel at Madison Square Garden (with the help of his stinkingly rich publishing boss William Randolph Hearst) that would make the Mob's grip on boxing health-threateningly strong. And Jacobs, the urchin from the West Side, was right in the thick of it with all of them.

Into this rich mix came men of suitably dubious character. You can imagine they were not turned away. This was a milieu that relied on a certain degree of laxity in morals. And then, the party crashers got a helpful little nudge they could hardly believe.

How the Mob got into an unchallengeable position of power in boxing from the 1920s until at least 1960 can be laid at the door of two well-meaning fools from America's Midwest. Andrew John Volstead was a Republican lawyer from the hamlet of Granite Falls, Minnesota, and Wayne Wheeler, of little Brookfield, Ohio, was a stiff-necked, teetotal hick who also went into law and was behind the hugely influential Anti-Saloon League.

In 1920, Volstead, advised by Wheeler, had voted in the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, banning the manufacture and consumption of any drink containing more than 0.5 percent alcohol. In New York, authorities closed down 15,000 licensed premises. Before they had poured the booze in the Hudson, 30,000 speakeasies had opened their hidden doors. Within five years, that number had grown to at least 100,000.

And still fans thronged to the Garden, juiced up illegally and not giving a damn.

Crime, meanwhile, outpaced the zeal of the crime busters chasing down illegal booze. And there to cash in were gangsters who now had a sympathetic constituency of millions—ordinary, thirsty citizens who came to view the police with growing irreverence.

“The national prohibition of alcohol—the ‘noble experiment’—was undertaken to reduce crime and corruption, solve social problems, reduce the tax burden created by prisons and poorhouses, and improve health and hygiene in America,” wrote the American economist Mark Thornton.

Instead, it spawned the most complete expansion of organized gangsterism the world has ever seen. Prohibition gave birth to the Mob as we know it. It changed the moral landscape forever. Legal jobs disappeared. Decent people were driven to crime. What was considered wrong once became the norm. Stealing, casual violence, and deceit spread. And, most tellingly, so lucrative was bootlegging, the preserve of the established mobsters, that they turned themselves into businesses. This was the genesis of organized crime in America. The phenomenon grew with names attached: the Syndicate, the Outfit, and, chillingly, their dedicated killing unit, Murder Inc.

Variously, the virus-strength spread of brilliantly marshalled illegality has been seen as the work of the Mafia, as well as the myriad ethnic gangs in ghettos all over the country. Really, they should share the credit with Volstead, Wheeler, and the boneheaded politicians who voted for Prohibition. But for their puritanical idiocy, we might never have heard of such successful criminals as Al Capone, Bugs Moran, and the O'Bannions.

It's hard to comprehend the impact of this legislation from a distance—except by the startling statistics: murders and serious assault went up by 13 percent; lesser crimes increased by 9 percent; prisons bulged by an extraordinary 561 percent.

So, sloshed and wild, New York, indeed all of America, danced the Charleston. They hung from the wings of biplanes that flew over Manhattan. They believed for a while in their own immortality. It was a decade made for Gatsby and excess, all the time pregnant with the certainty of retribution and collapse.

The working classes made heroes of the bootleggers. The Mob seized their opportunity and established such underground hegemony they were virtually untouchable. Americans did not believe, for a variety of reasons (fear, complacency, convenience), that there was anything in it for them to snitch on the criminals who sold them their rum and beer.

A far greater ill visited upon society than sly drinking was the spread of the protection rackets, which instilled fear even in men of physical courage. Some of those boxed for a living, but their fists were useless against the hoodlums who raked the streets of New York and other cities with submachine guns from the safety of their passing Model T Fords.

The lotus-eaters were being driven underground, into the speakeasies, dealing in the dark. Then, at the very time the reactionaries were winning socially, boxing, of all sports, decided to reach for respectability.

Fist fighting in all its forms had, since Georgian days, struggled to stay a step ahead of the law. The National Sporting Club, formed in 1881, regarded itself as boxing's gatekeeper, regulating titles and weights. But boxing grew with such speed after World War I that no private members’ club in London was going to contain the ambitions of the trade's rising entrepreneurs in New York.

On the face of it, the urge to cleanse seemed to be spreading from the bars to the ring. The New York State Athletic Commission was formed in 1920 to oversee the Walker Law, a piece of legislation that entertained professional fighting as long as it subscribed to the law's jurisdiction of the commission. In time, the NYSAC established influence over similar organizations in other states—and the world.

Inevitably, however, there were splits from the very start. In 1921, the rest of fighting America set up the National Boxing Association. Anarchy was up and running.

This served only to encourage the mobsters to move in on boxing with saliva dripping through their grins. They did not like regulation, but they did not mind the appearance of regulation—nor its confusing and chaotic replication. This was turf they could exploit, and the vultures were quick to land. Arnold Rothstein, the man rumored to have fixed the 1919 World Series with the help of the former world featherweight champion Abe Attell, would go to the fights then hold court at Lindy's, at Seventh Avenue at 53rd Street, a place where you could get bagels, booze, and the skinny on the next big fight. He would sit ringside at the Garden, handing out threats and favors to whoever he chose. In Chicago, Al Capone, a fight fan but bigger enthusiast of making money, bullied his way into the affections of promoters and managers.

Whatever arms were twisted for whatever result, there were still great fights at the Garden—such as the contest in 1922 between Harry Greb, who trained on sex and illegal liquor, and the upright Catholic intellectual Gene Tunney. Tunney, who liked to think of himself as a man of letters and who numbered George Bernard Shaw among his friends, was handed his only defeat by Greb, a man for whom reading and writing were not so much chores as irrelevant, except when filling out betting slips. It was a victory for the bad guys. There would be many more.

Young hoods rubbed shoulders with Babe Ruth, who'd moved to New York from Boston in 1920, and in April of 1923 hit a home run to open Yankee Stadium (within ten days of the opening of Wembley Stadium and the White Horse FA Cup Final). These were thrilling, dangerous days, full of adventure for anyone game enough to try their luck with the city's lowlife.

As Yankee Stadium was going up, Madison Square Garden II, White's gauche monument to a bygone age, was about to be reduced to rubble. America was moving on at a furious lick. Nothing was expected to last, except the myths. America lived for today, furiously. The sage Westbrook Pegler called it “the era of wonderful nonsense,” and much of it would be played out on the canvas stretched across the ring of all the Gardens.

The cream of New York's crime scene attended the last fight night at Garden II on 25th Street. It was May 5, 1925, an evening that dripped in schmaltz. Tiny Joe Humphries, the Michael Buffer of his day, wiped the traces of tears from his eyes, dragged down the overhead microphone, and intoned with all the solemnity he could muster (which was considerable): “Before presenting the stellar attraction in this, the final contest in our beloved home, I wish to say this marks the ‘crossing of the bar’ for this venerable old arena that has stood the acid test these memorable years. And let us pay tribute to Tex Rickard and the other great gentlemen and sportsmen who have assembled within these hallowed portals.”

Characterizing Rickard as “a great gentleman” stretched the sinews of old Joe's irony cells. Only three years earlier Tex had to draw on every smart friend he had, from politicians to lawyers, to extract himself from messy allegations that he'd pestered young girls. Old Joe soldiered on nevertheless. You could almost hear the violins from some celestial eyrie as he wound up: “Goodbye then, old temple, farewell to thee, oh Goddess Diana standing on your tower. Goodnight all . . . until we meet again!”

Cue thunderous reception—and on with the motley.

The closer that summer's night of 1925 brought together Johnny “The Scotch Wop” Dundee (he was born in Sciacca, Sicily, and grew up in New York as Giuseppe Carrora until his pro career started and he made an apparent nod toward a Caledonian constituency) and Sid Terris over twelve rounds at featherweight. Sid won on points.

When the tumult subsided, and the boxers gathered together their kit bags to leave that Garden for the last time, one John F. Mullins strode into the ring in the distinctive colors of the Fighting 69th, bedecked with his war medals, and played taps. Hallelujah!

This was the height of the roaring twenties, and Rickard's reign at Garden III, although it would be brief, was about to begin. The bootleggers, criminals, and various investors could hardly wait. Rickard, who'd promoted Jack Dempsey, co-opted the future New York State governor W. Averill Harriman to join his consortium of investors at the new establishment. In the hectic tempo of the decade, it took a mere 249 days to build the place on Eighth Avenue and 49th Street.

By most authoritative accounts, the first fighters to step into the new ring at Garden III were Paul Berlenbach and Jack Delaney, on Friday, December 11, 1925. Rickard was the promoter—alongside one Vince McMahon, the grandfather of the Vince McMahon known to wrestling fans today as the owner of and sometime participant in World Wrestling Entertainment.

Berlenbach and Delaney contested Berlenbach's light heavyweight title over the championship distance of the day, fifteen rounds, and, inevitably, not all was as it seemed. Some of the 17,575 customers who'd filed in from the speakeasies around Broadway that night no doubt imagined Delaney was Irish, a sure ticket-selling bonus in those days. Jack was, in fact, a French Canadian called Ovila Chapdelaine. So, for the purposes of commerce, the chap Delaine morphed into the chap Delaney. We can be reasonably sure Paul did not change his name to Berlenbach; most things German had little cachet after the Great War.

Whatever their real names or worth as fighting men, this is how the fight was recorded in the papers of the day: “Floored for a count of three in the fourth and punched groggy in the sixth and seventh, Berlenbach came back in the last six rounds with a stirring rally which saved for him the title he had wrested from Mike McTigue. His margin of victory was close, however, for newspapermen at ringside gave him only seven rounds, to six for the challenger, while two were even. . . . But the outstanding factor in his success was indomitable courage in the face of almost certain defeat.”

Rickard pushed that fight as the first in the new Garden. However, a disputed and little-known version exists that maintains the first fight in the new 1925 ring occurred three nights earlier, an amateur flyweight contest between Jack McDermott and Johnny Erickson. But no respected archivist has been able to confirm it took place.

What is not in dispute is that Rickard died on January 6, 1929, cut down at fifty-nine after an operation for appendicitis went wrong. It was nine months before the Wall Street Crash, not a bad time to check out. He left behind a string of memorable nights. The fighters who flocked to New York in the twenties, most of them performing at the Garden, most of them paid by Rickard, included Benny Leonard, Jack Dempsey, Jimmy Wilde, Ted Kid Lewis, Jack Kid Berg, Teddy Baldock, Georges Carpentier, Mickey Walker, Jack Britton, Irishman Mike McTigue, Pancho Villa, Luis Firpo, Harry Greb, Jimmy McLarnin, Jack Sharkey, Tommy Loughran, and Max Schmeling.

As the twenties closed, America was still “dry.” But citizens were tired of Prohibition, tired of big government, tired of being pushed around. The restrictions spluttered on until 1933, as the Depression wiped out jobs and hope. In the thirteen years of its life, Prohibition had given the Mob time to establish the sort of dominance it had dreamed of. The gangsters had control of the triple thrills of drinking, gambling, and fighting. Like the financial crisis sweeping the world, nobody knew how, where, or when it would end.

What everyone knew was the Garden was now the hub of boxing, the nation's, the world's most accessible and glamorous sports entertainment. The lights of Broadway had worked their magic yet again.

This was the state of the game when Mike Jacobs, now near fifty, aspired to step into Rickard's shoes. He'd hung in there, insinuating himself deeper into the upper reaches of the business's hierarchy. He knew every fighter, manager, and promoter in the business. He didn't necessarily like them, and most of those he did business with didn't much care for him. Surely, though, he would be the new Rickard.

Not straight away. The old power structure remained in place. The Garden was not there to be taken without a fight. It was in the hands of people who loved power, influence, and money just as much as Jacobs and his friends did. The expatriate Liverpudlian Jimmy Johnston was the matchmaker at the Garden and would remain so for a few years yet. But Jacobs was a patient man. And his associates had the sort of money that brooked no argument. His friendship with Damon Runyon, in particular, would prove crucial in the years to come.