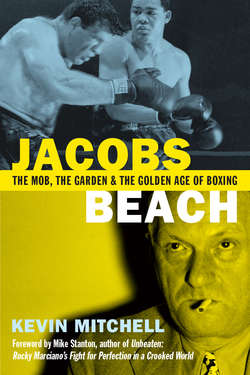

Читать книгу Jacobs Beach: The Mob, the Garden and the Golden Age of Boxing - Kevin Mitchell J. - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 2

The Ring Is Dead

ОглавлениеThere was a party in the Garden in September of 2007, but, for once, Muhammad Ali couldn't make it. He was a palsied shadow of himself, sitting quietly at home in Louisville, sixty-five years old, tended by his wife and nurse, Lonnie, and informed of the story secondhand by the friends who invariably descended upon him whenever boxing hit the news. How he would have loved to make the trip to New York. It was there, thirty-six years earlier, that he and Joe Frazier had given the Garden and the world one of their sport's most enthralling contests, the Fight of the Century. But that was just an entry in his scrapbook now for the man who saved boxing, as the news filtered through about the end of an era.

What appeared in Ali's newspaper in Kentucky that morning was a bulletin from the Associated Press, issued at 4:35 p.m. (Eastern time) the previous day, the 18th. Datelined Canastota, New York, it read: “After 82 years, Madison Square Garden will retire its storied boxing ring and donate it to the International Boxing Hall of Fame, where it will go on display this fall.”

This was the ring in which LaMotta first fought, and lost to, Sugar Ray Robinson, in 1942.

This was the ring in which Rocky Marciano knocked out Joe Louis in the Brown Bomber's last fight, in 1951.

This was the ring where Randolph Turpin brought the crowd to their feet in losing heroically to Carl “Bobo” Olson in 1953.

This was the ring where Joe Louis was lucky to get the decision against Jersey Joe Walcott in 1947, and where Billy Graham was robbed against Kid Gavilan in 1951—as was Lennox Lewis against Evander Holyfield in 1999.

This was the ring where Lou Ambers, Tony Canzoneri, Beau Jack, Dick Tiger, Ken Buchanan, Roberto Duran, Fritzie Zivic, Ike Williams, Joe Frazier, and Muhammad Ali thrilled, shocked, and amazed us.

This was some ring.

Now, in one short sentence devoid of sentiment—as is the detached way of wire services—a collection of nuts and bolts was to be buried, not without ceremony but with little regret outside the fight community.

The following morning in New York, a big man, wearing a smile permanently wreathed in sardonic double meaning, stood in the middle of the pensioned-off ring and boomed: “The ring is dead! Long live the ring! Heh! Heh!” The preeminent salesman of his or anyone else's time, Don King, as ever, had found quotable pith with which to put his stamp on an upcoming promotion in the Garden. There would be one last fight in the old ring, he said, and then we could start spilling blood in a brand-new one!

As it happens, there would not be another fight in the old ring. One of the proposed antagonists, Oleg Maskaev, was injured and the fight was called off. Another boxing mirage.

King loved the Garden, not wholly out of sentiment. He was a student of history, and used it constantly to lend his promotions glamour and legitimacy, capitalizing on the allure of boxing's past. Certainly, King might be sad to see the old ring go. But he was still standing. At the time of writing, the King is not dead. And we would not wish it so, even if there is a fat parish of enemies out there who disagree with that take on the subject. What a life he's led. What lives he's marred and, to be fair, enhanced. In the late forties, while LaMotta and the Mob were getting acquainted in New York, King threw a few punches as a skinny teenage flyweight back in Cleveland. He won a couple, then quit the sport after being knocked out in his fourth bout. Like the guy who stole Cassius Clay's bicycle in Louisville and led him to take up boxing as a bullied adolescent, the long-forgotten schoolboy boxer who put Don King's lights out lives anonymously forever in boxing's hall of myths.

When King gave breathless birth to his valedictory over the sacred ring in Madison Square Garden—one of hundreds for which he will be remembered when he is eventually laid to rest by gout or universal schadenfreude—the roped square was on its way to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in quiet Canastota. Rebuilt and revered, it resides as a reminder of the skulduggery and high times that took place in what for most of the twentieth century was the most revered arena in sport.

Nobody can be sure how many fighters stepped through the ropes of the most famous Garden ring over the course of eighty-two years. We can be certain, though, that the last title fight there was on Saturday, June 9, 2007, when Miguel Cotto of Puerto Rico stopped Zab Judah of Brooklyn in the eleventh of twelve scheduled rounds to retain his World Boxing Association welterweight belt in front of 20,658 fans, most of them New York Puerto Rican supporters of the champion. It was the biggest crowd the venue had seen for a championship bout outside the heavyweight division.

The fight was worthy of the surroundings. The ghosts of the Garden would not be disappointed, by either the class of the winner or the bloody-minded courage of the loser. This dirty, glorious space had always celebrated heroics and, when required, drowned perceived tankers and bums in a hail of derision. Now, as worn out and used and useless as a washed-up fighter, the ring was being laid to rest for good.

To fighters, the ring was a place of work; to admirers of architecture and engineering, it was a work of art. It was a minor marvel from a time when detail and artisanship mattered. The brass was polished so assiduously, it is claimed, that, when TV cameras fell on it in the fifties, executives complained there was too much glare for the cameras—much as they had pointed out to the advisers of Dwight D. Eisenhower that his shiny dome was a distraction to both the cameraman and the electorate when he ran for the presidency in 1952.

The ring wasn't always on TV, though, and it wasn't always fixed in place in the Garden. It was moved about like a shrine, from the Garden to Yankee Stadium, the Polo Grounds, even a gym in Little Italy. But its home was on Broadway.

It measured 342 square feet, eighteen feet, six inches on each side inside the ropes—smaller than today's twenty-foot-by-twenty-foot rings—weighed more than a ton, and was held together through a complex set of 132 interlocking joints. A lot of heads hit the canvas (some more willingly than others), which was replaced periodically, as were the padding and the ropes, up against which wily veterans would scrape the backs of bright-eyed novices.

It was the fighters’ stage, where no man could lie to himself for very long (unless paid to do so). The canvas, ropes, and posts are as blessed in boxing as the altar is in religion—a place of worship, and, more often than some people would like to admit, a place of sacrifice.

Why a ring, why square not circular? The ring is the accidental invention of the Georgian bare-knucklers who stepped on to whatever patch of grass was available and far enough from the unwelcome attentions of the law to accommodate the bloodlust of the Fancy. There they'd face off, in deepest Surrey or Hampshire, maybe Kent or Bristol or Yorkshire, surrounded by four wooden posts and some rope, erected not for any legislated purpose of keeping order between the pugilists but to hold at bay the intoxicated mob. It was square only because the prizefighters’ seconds stood opposite each other and those entrusted with policing the occasion would put a stake beside them, upon which they'd place their coats and hats; to run the rope around the fighters, it made sense to have two more supporting stakes, on the other diagonal, and on these were placed the bets, or stakes, in the care of some hopefully reputable third party. Thus the square ring simultaneously became geometrically incongruous and indestructible in the imagination.

And so they gathered in the Garden one last time to pay homage to an inanimate object, with the very animated Don at the center, the fighters, as ever, all around the man who sometimes made them rich and celebrated, sometimes poor and discarded.

Something more subtle than a King monologue was at work that autumn of 2007. There was a case for tearing down the old ring, certainly; it was starting to creak dangerously. But so was boxing. This was more than the transfer of some metal, wood, and canvas from New York to a museum in a small upstate town. The reality was that the sport was in trouble—and now another piece of the fragile edifice holding it together had been stripped and consigned to a museum. Represented as regeneration by interested parties, taking down the ring also symbolized the dismantling of the fight game. It would not end there. Even as the carpenters were packing the ring into crates, architects, engineers, and lawyers at nearby city hall were talking seriously about the demise of an even more obvious boxing institution: Madison Square Garden itself.

The one still standing, the one from which the ring had been plucked, is the fourth Garden. It had been built over Pennsylvania Station, on Eighth Avenue between 32nd and 33rd Street, forty years before and had operated since 1968. Now, it seemed, as part of the endless odyssey, there might be a fifth Garden. On Tuesday, October 23, 2007—five weeks after the ring had been dismantled—the Empire State Development Corporation unveiled a $14 billion plan to level the old building and put up a new one nearby on Ninth Avenue. Will it happen? Nobody knows. As ever in boxing, we will have to wait until fight night.

The ring is dead. Long live the ring.