Читать книгу The Colored Waiting Room - Kevin Shird - Страница 5

Introduction

ОглавлениеI remember the first time I saw images from the Jim Crow era: photographs of signs that read “Whites Only” or “No Negroes Allowed.” I was about ten years old at the time. Those signs, it was explained to me, were a symbol of the many dehumanizing laws and social practices that prompted the beginning of the American civil rights movement. The photographs that followed, images of people who weren’t allowed entrance to places, or could only go into lesser quality ones designated “For Colored People,” were black, like me, and their skin color was the only reason for the segregation enforced on them. If I had been alive when they were and living where they were, I, too, would have been denied entrance.

Yet the photos meant very little to me, and I was emotionally detached from what the people in them were experiencing. I had not experienced racism at that time in my life, and I knew very little of its history. I grew up in Baltimore City and nearly everyone I knew was black, and the few white people I’d encountered in my short time on earth seemed harmless enough. I’d never been told I couldn’t go into a store or drink from a fountain or swim in a pool because of the color of my skin. So when I first saw those demeaning placards, emblems of a hate-filled and dangerous culture, I didn’t feel the trauma and the pain that millions of black people suffered living under those conditions. Those labels that represented segregation seemed like they couldn’t have been real, even though there were people around me who were old enough to remember the period when those signs were posted and their rules were enforced.

Fast forward to much later in my life, in 2013, and modern-day racism is unfolding in front of my eyes, all our eyes. We’re not reading about it in a history book: we’re seeing it on the daily news, on social media, or in person. The racism isn’t new, but what shines a bright light on it is the public furor and demonstrations following the acquittal of a man who shot and killed a seventeen year old in Sanford, Florida.

Social media spreads the news like wildfire and protests erupt. #BlackLivesMatter goes viral. It becomes the name of an activist organization and is chanted by protestors and written boldly on signs. It gets used at protests that follow later that year and in ones to come. Black people are putting their foot down, saying enough is enough, that blacks need to not be assumed to be guilty of crimes, to be troublemakers—or worse, deserving of being accosted by police when the police know they are innocent, or set up for crimes—that they deserve respect, like white people more frequently get. The protestors are calling for justice and equality, something that should not be controversial, but not everyone sees it this way. Some people even call the group racist, as if black equality would somehow hurt white people. #AllLivesMatter trends on social media and then #WhiteLivesMatter and #BlueLivesMatter. I begin looking out for #DolphinLivesMatter; why not continue with the absurd, why not continue missing the point?

It’s been unsettling for me to think that there might be more Americans concerned about the phrase “Black Lives Matter” than about the need for black people, and like-minded activists of all races, to combat systemic racism. But I shouldn’t have been surprised. America has a long history of being averse to people who decide to mount a vigorous campaign to protect civil rights and stand up against discrimination and injustice. This practice didn’t end when we left behind the era of the Black Panthers and bell-bottoms. Pages in the history books of our children may repeat themes in the pages of ones I grew up with. Are we then having a second-wave civil rights movement? Could looking back at the original movement contextualize ours today?

There’s a significant disconnect between the baby boomers of yesterday, who are old enough to remember a very different world, and a new generation of iPhone fanatics and Starbucks aficionados with short attention spans. Many people in this internet-enabled era have little interest in what happened two days ago, let alone fifty years ago before most of us were even born. How can we ensure that the sacrifices made many years ago to secure our civil rights are respected and understood by the generations that follow? How do we connect the dots between the struggles of the 1950s and 1960s against segregation and the struggles we face today as we continue to strive for social justice in America? I believe that knowledge of the past can help us draft a blueprint to fix what’s broken in our society today, but we have to be willing to look back to look forward.

During the American civil rights movement, the media played a key role in the movement’s success. The images shown on television were critical: protestors being brutalized by police, students being blasted with fire hoses and set upon by vicious attack dogs. If not for the media’s role in broadcasting those repulsive images, America might not have been so inclined to become sympathetic to the cause

The media still plays an invaluable role in social progress, but much of it is distributed not on the airwaves but on the internet. We primarily consume our media online today, often through social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter. Consuming these modern media images can make us feel as though we were present at the events they show, allowing us to feel more connected to the people who experienced them. Similarly, reading about the American civil rights movement online and watching videos of the brave and courageous protesters, who were often bludgeoned and brutalized for their opposition, can make us feel like we were there with them. It’s painful, but it needs to be. Otherwise you’re just a bystander.

One step above viewing media of the events or reading about them is being able to speak with someone who actually experienced them, and having the ability to ask questions. There are people alive today who can remember and share what happened. There’s been a push to record the words of survivors of atrocities, like the Holocaust, before this generation completely passes away so that there is proof of what they endured. I believe we need the people who weathered segregation to tell their experiences too. Their words must also be recorded as proof of an atrocity. We need to understand, and remember, what they went through.

–

The way I first learned about the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., as well as the American civil rights movement, was very unorthodox. Today, it’s almost taboo for an African American not to know about the life and legacy of one of the most important people in our history. In fact, many of us who aren’t versed in his accomplishments have learned over the years to camouflage this deficit to avoid embarrassment. We might memorize a line or two from King’s most popular speeches, so that we are ready to recite them if pressed to do so. But when I was a kid, I wasn’t that sophisticated, and I wasn’t great at camouflaging the truth.

I was in the fifth grade, attending public school in Baltimore City, when I first began to hear about a man named Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Back then, I thought he was a famous singer. Yes, you read that right: For a few years, in grade school, I thought that the Nobel Peace Prize–winning leader of the movement for black freedom was just another man who entertained America. I know it sounds ridiculous today, but let me explain.

The reason I believed this was because the subject of King’s life and legacy was only taught to us once a year. February was Black History Month, the time when the accomplishments of legendary African American entertainers like Cab Calloway, John Coltrane, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Billy Holiday, Louis Armstrong, and Nat King Cole were highlighted. Since there was no other time devoted to the subject of African American accomplishments, discussions about their lives were usually mingled together with discussions about black social and political leaders, abolitionists and revolutionaries like Harriet Tubman, W. E. B. Du Bois, Nat Turner, Frederick Douglass, and Booker T. Washington. Once a year, during Black History Month, the biographies of these colossal figures in our history were all lumped together in one big pot like alphabet soup. A young public-school student had only twenty-eight days in the month of February to learn three hundred years of African American history.

As a result, the public schools I attended in Baltimore didn’t devote much time to teaching us about the impact King or the civil rights movement had on America. We weren’t taught the details: how King, through nonviolent protests and activism, forced the integration of lunch counters and public transportation systems in the South, and established legally mandated voting-rights equality that changed the trajectory of America. Besides Black History Month, there were no other times during the school year when King was the subject of discussion in class, so his numerous accomplishments and legacy were not crystal clear to me. At the time, his birthday had not yet been recognized as a national holiday and was not celebrated in all fifty states. Even when King’s life was the main topic in the classroom, he was never talked about with the same level of importance as other twentieth-century leaders, like President John F. Kennedy, or even international ones like Mahatma Gandhi. Although King’s impact on society was just as significant, he was not talked about in the same vein as other men who were revered for their willingness to fight for the things that are noble about our humanity.

When I was in grade school, Michael Jackson and Muhammad Ali were the two most important black men, in my mind, to ever walk the streets of America. Michael Jackson had just begun to perform his world-famous moonwalk dance while wearing that ugly white sequined glove, and Ali, my all-time favorite athlete, was still a superstar, although he was beginning to age beyond his boxing prime.

The light bulb in my young mind wasn’t turned on until middle school. That’s when I began to gradually understand that King was nobody’s singer. Nowadays, when I think back, it’s incredible to me that I lacked so much knowledge on such an important subject. Was I just another public-school student who had fallen through the cracks, or was I another victim of society’s attempt to whitewash the legacy of one of the most consequential black leaders the world has ever known?

Sometimes I wish I had been raised by parents who were Afrocentric, or maybe even Black Panther sympathizers who wore cool black leather jackets and protested systemic oppression. Maybe then there would have been all kinds of books lying around the house to enlighten me about the long history of black America. I wish that I had read books about King when I was younger, and about the early days of Malcolm X’s life, when he served time inside a Massachusetts state prison. It might have been enlightening for me to browse through the pages of books like Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave, or Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. There’s no doubt in my mind that if I had been exposed to the literature and the history of African American heroes when I was young, my knowledge of their lives—and possibly my understanding of my own—would be much more complete today. One of the important things we get from learning history—one reason why it matters so much whose stories get told—is a sense of being able to contextualize, to see how we fit into a world that very rarely gets directly explained to us.

The stories of Harriett Tubman guiding escaped slaves through Maryland into Delaware, on their way to freedom, would have been powerful to read. Maybe I would have known more about a talented black man named Benjamin Banneker who lived in the 1700s, a clockmaker and astronomer—a rare talent for the son of a former slave, who was self-taught and had little formal education. Studying these leaders and contributors to our humanity earlier in my life and understanding their legacies could have made a big difference in how I viewed my culture and how I viewed myself. Having serious gaps in my education on black history still haunts me today, and I’m still trying to make up for that loss.

In the last few years, however, I’ve started to think that I may have been a little too hard on myself. I began to realize that I wasn’t the only one with a deficit of knowledge about the civil rights era and the accomplishments of Martin Luther King Jr., and I’m not the only person who could’ve used a few extra days of Black History Month, or who should have hung around with the smart kids who read books about the movement and were more in tune with black history. There are many of us who would have failed an African American history test when we were in school. That’s the reason I was so excited when I met an eighty-four-year-old man from Montgomery, Alabama, who knows more than most about that period in time.

–

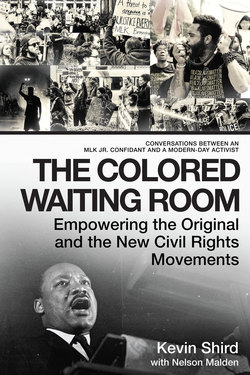

Nelson Malden is an accomplished man by any measure. He is an alumnus of Alabama State University, where he majored in political science, and a member of Montgomery’s famous Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. He’s a veteran of the United States Navy, a black man who at one time took an oath to defend his country, a time when his country was not as inclined to defend his most basic liberties. He was the first black person in Montgomery to ever run for public office, and he distributed the Southern Courier newspaper, one of the few newspapers in the South to cover the African American community. He was also the barber, and close friend, of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

I met Nelson in 2016, when he was in my hometown of Baltimore along with his niece and his great-niece. He was participating in an onstage discussion at the Motor House, a community performance space, about the golden years of the American civil rights movement. When Nelson was a young man, in the 1950s and 1960s, he spent many years actively participating in the nonviolent civil rights movement in Montgomery, Alabama, where he lived—a local movement that would have historic ramifications for the rest of America.

In no time at all, I realized that Nelson was exactly the type of person I needed to talk with. He had vast knowledge about and experience of a time in America that most people could only read about in books or watch in a documentary. It was there in Baltimore—during my first conversation with Nelson, backstage after the event that night—that I became eager to get to him, to hear his stories. Nelson was telling me about his life growing up in America back when racism was far more blatant than it is today, especially in the South, and particularly in Montgomery, a racist hotspot under the law of the infamous Governor George Wallace. It seemed to me that Nelson could, from his first person experience, help me understand the American civil rights movement in a three-dimensional way, a way that I’d never understood it before. And this, in turn, I thought to myself, might help me understand what led to the current form of racism that exists in America. Yet I had no idea then just how close Nelson was to the center of this history. It was one of the incredible things about him that I would discover as our friendship grew.

Nelson is optimistic that race relations in America will continue to evolve toward “the Dream” that King spoke about. Even after his friend and client was shot and killed in Memphis in 1968, Nelson never stopped believing that King’s dream would live on. He still remembers how thousands of enthusiastic people assembled in the nation’s capital for the March on Washington. He also remembers Reverend King (as he called him) receiving the Noble Peace Prize and how proud he was of his friend’s accomplishment.

Nelson spoke to me of segregation that he had personally endured. There was rampant segregation in the South, everywhere from schools to public beaches, and there was a daily fear of physical violence, even death, at the hands of white people. His eyes lit up when he spoke about such things as how incensed he was when black students in Birmingham were violently attacked during their nonviolent lunch counter sit-ins.

His expression turned somber when he recalled the footage he saw on television of men and women being savagely beaten in Selma in 1965 by Alabama State Troopers. At the time he was a young supporter of the movement, and as the brave participants in the fight for voting rights slowly began to arrive on the outskirts of Montgomery after the long march from Selma, he was there waiting with hundreds of others to greet them. Their stories of being spat on, called “nigger,” and shot at by white segregationists who were bursting with hatred are still vivid in his mind. But he also talks of looking into the eyes of the marchers that day and seeing nothing but sheer will and determination. He says that they were brave and that they were willing to die for what they believed in.

These events were some of the things that Nelson and his most famous client, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., spoke about when King was in the barber chair at the Malden Brothers Barbershop in Montgomery.

I spent nearly a year speaking regularly with Nelson Malden and visiting him often, recording everything he said on my iPhone, and then transcribing it. I was soaking up knowledge and trying to connect the dots between the civil rights movement of yesterday and the social justice movement of today. Most days I was like a fly on the wall, listening intently to the eighty-four-year-old former barber as he recounted his experiences and described his cherished friendship with an iconic civil rights leader. Some days I was smiling while listening to Nelson talk about King’s humor; other days there were tears in my eyes and I was angered by the systemic mistreatment of African Americans, then and now. As I came to understand it, the civil rights struggle of today isn’t identical to the struggle of yesterday, but it is just as significant.

Today, after all the pain and disappointments, as well as the triumphs, there’s one thing Nelson understands without question: When it comes to race, we still have a lot of work to do in this country.