Читать книгу The Colored Waiting Room - Kevin Shird - Страница 7

1: Heading South

ОглавлениеAfter I met Nelson Malden for the first time in Baltimore, we established the beginning of a friendship, and it was through that friendship that I began to learn things I had never understood before. Instantly, I became a student of history, soaking up everything I could about “the movement,” as it was often known, and about an era that was totally unfamiliar to me. This, I knew, was my chance to finally fill a void that had been lingering for most of my life. I was like an empty vessel being filled with a valuable raw commodity, a vital substance that would soon alter the way I saw the world.

Soon I was calling Nelson on the phone every week at his home in Montgomery, Alabama, hungry for knowledge. One day, he began telling me about a close friendship he’d had with an iconic leader in the movement, and I was blown away.

“Hold up. You were friends with whom?”

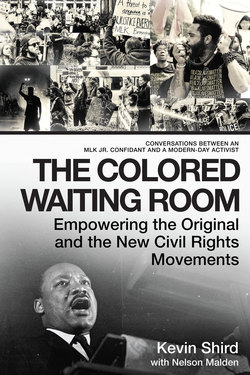

To my shock, it turned out that Nelson had been very good friends with none other than Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who was a regular at his barbershop in Montgomery through the 1950s and 1960s. King began going to the barbershop every week, right before Rosa Parks’s arrest for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white man brought the civil rights movement in Montgomery to national headlines. As Nelson described his decade-long association friendship with King, I was in near disbelief. I was on a call with someone who was not only an active member of the civil rights movement himself, but also a friend of the legendary Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. I listened eagerly as he told me about the time they spent together in the South during a very volatile period in this nation’s history.

One day, Nelson invited me down south to talk more in person. Of course I jumped at the opportunity and soon after, on a warm summer day in 2017, I arrived for the first time in my life in the Deep South, in the city of Montgomery, Alabama, commonly known to the locals as “the Gump.” I had booked an early morning flight on Southwest Airlines leaving from the Baltimore-Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport in Baltimore (which is named, I should point out, for the first African American justice of the US Supreme Court) for Alabama. After arriving at the Montgomery Regional Airport, I took the fifteen-minute taxi ride downtown to the Renaissance Montgomery Hotel and Spa on Tallapoosa Street.

Never having traveled before in the Deep South—a place that had been described to me as a historic (and sometimes modern) hotbed of racism—I wasn’t sure what to expect. I had been told that the Renaissance was the nicest hotel in the city and booked it because the idea of having a comfortable room to return to each night gave me comfort. As I walked into its plush lobby, the hotel seemed to live up to its reputation. I checked in at the front desk, dropped my bags off in Room 822, and ran back outside to grab another taxi. I was already running late for my scheduled meeting with Nelson.

I didn’t realize until I arrived that our meeting place was an empty lot on S. Jackson Street. When I stepped out of the taxi, I looked to my left and saw my eighty-four-year-old friend standing there under the cool shade of a tall tree. Nelson was wearing tan slacks, a white short-sleeved button-up shirt, and a vintage hat to shield his head from the powerful Alabama sun.

Just like the first time I saw him, he reminded me of my grandfather Gradie Shird, who died when I was a young teenager. My grandfather raised twelve kids with my grandmother, so although it didn’t happen often, he had a lot of experience knocking young people upside the head and putting them in their places when necessary. He was a man’s man and had the knuckles to back it up.

Nelson was similarly mild-mannered, with a calm and relaxed demeanor, but he was nobody’s pushover. His mind was sharp, and he was articulate. I could see that he had taken care of himself over the years, and he said his health was excellent. He was easygoing and had a lot of style and class.

I was elated to see Nelson, but I was curious as to why we were meeting in an empty lot. This was my first time seeing him in person since we first met in Baltimore, months earlier.

“Hi there,” he said. “Is this your first time in Alabama?”

“Yes, it sure is.”

“Okay! In that case, we need to make sure that you get the chance to taste some good Alabama food while you’re here. We have to get you a big old plate of fried catfish, or shrimp and grits.”

One way to have a memorable time when traveling is to embrace the cuisine of your host city. The food is one of the things you’ll never forget about any place you visit. My mouth began to water at his suggestion, but then, just as quickly, our conversation shifted to the real reason I was here: to hear Nelson reflect on the many years of black triumph in the South, as well as those years of trepidation. As Nelson and I began talking, he spoke about the period that he referred to as the “old days.” It was a time when blacks in America had to fight for the right to be treated as equal citizens, a time when it was all too easy for blacks to be pushed aside by barriers that were both social and legal—and a time when anger at this injustice, in a supposedly free country, was reaching a boiling point. It was clear to me that the civil rights era was still fresh in Nelson’s mind, the source of memories, both good and bad, that he will never forget.

As Nelson and I stood there on Jackson Street, he began to explain to me why he had wanted to meet there, which still wasn’t clear to me. He told me that we were in Montgomery’s Centennial Hill neighborhood, a once segregated section of the city, which in the middle of the twentieth century was both the capital of Alabama and the epicenter of the American civil rights movement. The area was rich with history, and not only for the successes achieved here in the struggle for black freedom.

In the 1950s, Jackson Street was where black people in the South wanted to be—like Madison Avenue in New York, but much more intimate. For Nelson, it was where he had a front row seat to the American civil rights movement as it unfolded in real time. Many activists and leaders in the civil rights movement emerged from somewhere within a ten-block radius around Jackson Street. In 1954, King lived with his beautiful wife, Coretta Scott King, at 309 S. Jackson Street. With Reverend King residing one block away, there was a lot of activity in this neighborhood.

At the top of Jackson Street was the campus of Alabama State College, now Alabama State University. Alabama State was like an incubator for young black activists, encouraging them to become part of something bigger than themselves. Many students who attended the college were involved in the demonstrations and civil disobedience actions that took place in Montgomery and elsewhere across Alabama and the nation. They protested in the Montgomery streets, and they took trains and buses to other cities to march in their streets. They had no idea at the time how significant their impact would be, but they ultimately became just as important to the movement as the leaders that we know today.

Before I met Nelson, the Deep South was a place that I never had much interest in visiting. Now, standing there on a clear, hot day in the thick humidity of the summer, I couldn’t believe I’d never been there before. It had a rich history, a legacy etched in the pavement. In Nelson’s own words: “We were young, we were brave, and we were crazy sometimes, because we often put ourselves in harm’s way. But many positive outcomes were achieved during a time when all we wanted to do was to make a difference and all we wanted in return was equal rights.”

–

Nelson was born on November 8, 1933 in Monroeville, Alabama—also the birthplace, seven years earlier, of Harper Lee, author of To Kill a Mockingbird—and grew up in Pensacola, Florida. His father, born in 1896, and his mother, born in 1900, met in Monroeville in the early 1900s. His paternal grandfather was a slave until the Emancipation Proclamation, declared by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863. One of his maternal great-grandfathers was a white man.

The man who owned Nelson’s paternal grandfather was a prominent and wealthy builder who arrived in Monroeville in the mid-1800s to construct homes and other buildings. As a child, Nelson often wondered why his grandfather’s house was so well-built compared to other homes in the community. Later, he discovered that his grandfather had learned how to build homes from the white man who’d once owned him.

The white great-grandfather had a wife and children, but also two other families living in Monroeville with children he conceived and supported.

Let me explain: My mother’s grandfather was a white man who was married to a white woman, but he also had ten children with an African American woman and ten children with a Native American woman. The kids were all mixed race or mulatto, whatever word you want to use to describe them. Follow me? So, my mother’s father was half white and half black. His wife, my grandmother—my mother’s mother—was a pureblooded Indian from Monroeville.

My mother was mixed race and incredibly beautiful. Her complexion was very light, and her hair was long and black. I was very close with her. I was the youngest of seven boys, and she gave me the impression that I was the pretty boy in the family; she kept me dressed up all the time. But my father was a disciplinarian, and he wouldn’t let her love for her children interfere with his discipline.

Nelson’s father was a World War I veteran and had learned the importance of strong discipline while in the military. As a result, all his children managed to avoid the pitfalls of drugs and jail. Growing up in the segregated South, his father had had very few opportunities, and so he understood the importance of education; he wanted his sons to have a bright future with financial security. Starting when Nelson was old enough to go to school, when the family was in Pensacola, Nelson’s father had enrolled him in a private school with a tuition of fifty cents a day.

Nelson was diligent in pursuing education from there forward. After moving to Montgomery from Florida in 1952, he enrolled in Alabama State College, founded in 1867 by a group of freed slaves. The college was just a short walk from the College Hill Barbershop, where he worked with his brothers. Nelson would take a leave of absence midway through college to serve in the military, like his father before him, spending sixteen months in the United States Navy before receiving an honorable discharge. He then returned to Montgomery to continue working with his brothers and complete his education. When Nelson received his bachelor’s degree in political science, his father’s dream of having an educated youngest son was fulfilled.

Nelson met his loving wife Willodean, “Dee,” as she prefers to be called, in 1959, when she came in to the barbershop to get her hair cut. Four months later, on Valentine’s Day, 1960, they married. Dee was also well educated, a graduate of Alabama State College with a degree in elementary education. She worked as a teacher at an elementary school in Montgomery.

Nelson and Dee never had children. Throughout the fifty-eight years they’ve been together, it has been just the two of them, and they’ve stayed madly in love. They’ve vacationed around the world, sunbathing in places like Aruba, Bermuda, and Miami Beach and exploring big cities like Beijing and Shanghai.

As our conversation began to wrap up, Nelson suggested that I stay the night at his house. I declined, but I was moved by this striking example of Alabama’s world-renowned Southern hospitality.

–

In 1946, Nelson’s older brother, Spurgeon Malden, moved to Montgomery from his home in Pensacola, Florida. Two years later, in 1948, his other brother, Stephen Malden, moved to Montgomery and became a barber at College Hill after finishing high school in Pensacola. So the pattern was well established by 1952, when Nelson completed high school in Pensacola and he, too, moved to Montgomery. He enrolled in Alabama State College and likewise became a barber at College Hill, where his two brothers had already established a good relationship with the owner.

At that time, the College Hill Barbershop, located at the corner of Jackson and Hutchinson Streets in Montgomery’s Centennial Hill neighborhood, was the busiest black barbershop in the entire city of Montgomery. It was located about a block from Alabama State College and because of its proximity to the college campus, the barbershop was an assembly line of sorts for cutting the hair of black students, where a haircut normally cost them about $1.75. Most of Nelson’s clients were students, but he also cut the hair of many professors, who were among the African American elite in Montgomery at the time. Even the president of Alabama State College was a regular customer of College Hill, and so were most of the black doctors in Montgomery. Isaac Hathaway, one of the men commissioned by the United States Mint to create the first Booker T. Washington silver dollar, visited frequently, and Nelson had five or six clients who had PhDs, and others who were in the finance industry. Another regular client of Nelson’s was Vernon John, who was the pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church before Reverend King arrived. According to Nelson, Vernon John was the first black minister in the United States to have a sermon published in a national publication.

Since the barbershop’s clientele included some of Montgomery’s black social and political influencers, Nelson was just nineteen years old when he was first able to spend a great deal of time with some of the most important local and national black figures. Of that experience, he said that “College Hill was the kind of environment that included black intellectuals and we always had conversations about subjects that mattered”—a remarkable gift to a young man whose own education was not yet finished.

In 1954, when Nelson was a freshman college student, he became the personal barber to the then twenty-five-year-old Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. King first selected College Hill as the place to get his haircut as a matter of convenience: He lived down the street from the barbershop, and the church where he pastored, where he spent a considerable amount of time, was not far away. There were other barbershops in Montgomery, but because of segregation, there were only a few where African Americans could get their hair cut—and precisely because of that lack of choice, College Hill soon became more than just a barbershop.

King walked into the barbershop one day just as Nelson was about to rush off to his ten a.m. class at Alabama State College, but Nelson didn’t think anything of it. He recalls, “A prospective customer parked in front of the barbershop and came in asking who could give him a nice trim.” Nelson was initially nervous to do so—he never liked to start a client’s haircut after twenty minutes to the hour, because one head usually took him at least fifteen minutes. The semester had just started, and he didn’t want to be late, but on that morning, he told me, “I looked at this short black man who had just jumped out of a car, and I said to myself, ‘Oh, heck. I can knock him out in ten minutes.’”

As with any new customer, Nelson asked his name and where he was from. King told him he had recently moved to Montgomery and that he was the new preacher at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where Nelson was a member.

Once he had finished cutting King’s hair, Nelson handed him a mirror and asked if he liked the cut, to which King responded, “It’s pretty good.”

“Now, when you tell a barber that a haircut is ‘good,’ that’s somewhat of an insult,” Nelson told me with a big smile.

When Reverend King came back two weeks later, Nelson was busy working on another customer. Even though the other barber’s chair was vacant, King waited for him to finish. When Nelson’s chair opened up, the reverend came over and sat down, and Nelson began cutting his hair. He remembered the unenthusiastic assessment King had offered of his work the last time he was there, so Nelson said, “That must have been a pretty good haircut you got the last time you were here, huh?”

“You’re all right,” King said.

One question would soon arise.

Now, most of the time, after the second or third haircut, a new customer gives the barber a tip if they’re satisfied. But after I cut Martin’s hair at least seven or eight times, I noticed that he never gave me a tip. So one day I decided to use a little psychology on him, and I asked, “Reverend, when you finish preaching a sermon at church on Sunday morning, and the church members tell you that you delivered a good sermon, doesn’t that make you feel good?”

He said, “Yes.”

So, I continued, “When you go to a restaurant and you have a nice meal and the waitress gives you great service, in return, you give her a tip, right? Don’t you think that makes her feel good?”

He said, “Yes.”

Then Martin said to me, “Do you read your Bible? The Bible says you’re supposed to give 10 percent of your earnings in church. Do you give 10 percent of your earnings to the church?”

I responded by explaining, “Rev, I’m a student at Alabama State College right now. I can’t afford to give 10 percent of my earnings to the church.”

He said, “Well, I’m the pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, and I can’t afford to tip you, either.” Then we both began to laugh.

–

In 1958, twenty-five-year-old Nelson and his brothers, Stephen and Spurgeon, left College Hill to open the Malden Brothers Barbershop at 407 S. Jackson Street, on the bottom level of the Ben Moore Hotel. They were inspired by their father’s legacy, himself an entrepreneur and barber. Nelson’s brother knew the hotel’s owner, Mrs. Moore, whose husband was deceased. Because she wanted to see young black men become entrepreneurs and businessmen, Mrs. Moore gave the brothers a financial break, allowing them to pay only one hundred dollars per month to rent the space for their barbershop. During the time she was alive, she never increased their rent.

The Ben Moore Hotel was located on the corner of High and Jackson Streets, and it stood tall in the skyline in comparison to the other two- and three-story buildings in the area. The Ben Moore had the first license that allowed lodging for blacks in Montgomery, and it was one of the only hotels in Alabama where blacks could stay. It was referred to, in those years, as “the best hotel south of the Ohio River” for blacks, and was the centerpiece of the segregated section of Montgomery.

In those years, blacks didn’t have many options as to where to open a business in Montgomery. Jim Crow laws enforced racial segregation, and one of the many things prohibited to blacks was the opening of businesses outside segregated sections of the city. Segregation was overt oppression, and black Southerners were forced to live with it for almost one hundred years after the end of slavery in America. A black person couldn’t just go to any restaurant to eat or any barbershop to get a haircut.

The Ben Moore was frequented by the most elite black Southerners; some of the premier civil rights activists in Montgomery even lived there. Bayard Rustin, Dr. Benjamin Mays, and Mordecai Johnson, the first black president of Howard University, all stayed there for a time while working with others on strategies to fight the civil rights battle around America. On the hotel’s first floor was the Majestic Café, which was also black-owned and was an important meeting place in the black section of town and for black travelers visiting the city. Black musicians came to the Ben Moore to play jazz and perform in the rooftop garden of the hotel, which was referred to as the Afro Club. According to Nelson, the club boasted a clientele of beautiful, sophisticated, and intellectual African American women. “These were some of the most attractive black girls I had ever seen in my life,” he said. “They were all from the area or attended Alabama State.”

For the Malden brothers, opening a barbershop connected to the Ben Moore turned out to be a great business decision. Because of all the activity in the area, new clients were easy to come by, and having cut hair in College Hill for so many years, they had built solid client–barber relationships with many of their customers, who remained loyal when the Maldens opened their own shop. All the leading figures who were customers at College Hill, the doctors and professors, followed them to Jackson Street. When Reverend King followed, too, Nelson’s previous employers were devastated. And students continued to come as well, flooding in from Alabama State. Nelson estimated that at least 75 percent of the students at the college were regulars, as well as many of the famous Tuskegee Airmen, who often travelled from the nearby base to get haircuts. Even the black military men from Maxwell Field, later named Maxwell Air Force Base, became regulars. Legendary singers from the old school, like Little Richard and B.B. King, also stopped in from time to time.

The young minds and passionate personalities at the barbershop made its atmosphere electrifying. It was one of the few institutions of business in Montgomery where black people could sit together undisturbed and talk about anything and everything.

The black barbershop and the black church were the only places we had. At that time, we didn’t realize the value of the black barbershop. It was one of the few places where we could congregate and express ourselves in a community atmosphere. There were many subjects that we passionately discussed, like politics, the government, racism, and women. We could express what we really felt about issues that affected our lives. It was like a sanctuary, and that’s what made it so unique. And you could say things that you couldn’t say in the church. You couldn’t go to the church and talk about most of the things we talked about in the barbershop. In the barbershop, you could talk about anything that you wanted, like race, sports, or sex. You could talk about how hard Jackie Robinson hit the baseball in a game the previous night. When Joe Louis knocked out Max Schmeling, I remember people ran out of the barbershop and into the street, hollering and screaming, “Joe knocked out Max Schmeling, Joe knocked out Schmeling.” This was a place where we felt comfortable opening up and talking, almost like a second home.

King got the same style of haircut about once a week, often on a Saturday night, but sometimes, if he had a special speaking engagement early the next week, he’d come by the barbershop just to get a shape-up or have his mustache trimmed. While he was in the barber’s chair, he and Nelson often had casual conversations about his kids, the church, or whatever was going on in the news at the time. King spent a considerable amount of time in the Malden Brothers Barbershop after they opened at 407 S. Jackson Street, which was right down the street from King’s home at number 309. King would also come to the shop sometimes just to sit and read or write.

If two clients were in the barbershop that Nelson thought would benefit from knowing each other, he always made sure to make an introduction, but sometimes it didn’t go smoothly.

Here in the barbershop, we often had debates and discussions about whichever current events were in the news at the time—religion, race, sports, you name it! One of the best debates that I can recall was between Reverend King and a client of mine who was a sociology professor and the head of the sociology department at the Hampton Institute [a major institution for black higher education at the time]. He had relatives living down in south Alabama whom he would visit, but he’d stop in Montgomery to get his hair cut. He was a bona fide intellectual from head to toe. One day he came into the barbershop at a time when I had just finished cutting Reverend King’s hair. Reverend King was an intellectual as well, and he had a bachelor’s of science in sociology from Morehouse, so I thought it would be nice to introduce him to the professor. The professor was already familiar with Martin because by then he was well on his way to becoming a world-renowned leader.

I don’t remember how the topic came up, but I do remember when Reverend King said to the professor, “Morality is one of the strongest forces in the American family today.”

The sociology professor from the Hampton Institute disagreed with the reverend and said, “I beg your pardon, sir, but I believe that economics is the strongest force in the American family.” He went on to say, “When the European white men came to this country, one of the first things they did was to build some of the top universities in the New England area to educate themselves. When they got oranges in Florida, sugar cane in Louisiana, oil in Texas, grapes in California, and tobacco in Virginia, they built Wall Street to control the capital, and then they built West Point to defend it.” He said, “That is the United States of America.”

Reverend King said, “Have a good day, sir.”

I think that was one of the only times when the reverend didn’t win an intellectual discussion in the barbershop. He knew how to debate well, but he also knew how to have a conversation with the common man. King’s unique oratory skills were never intended to place himself above the people, but he used that communication skill to submerge himself in the community, where the people who mattered most to him were the common man.

I asked Nelson if King was always working on civil rights matters and he explained that King was a workaholic and travelled often, so he spent a lot of his downtime with his family. He often conducted meetings in the basement of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. The church building sometimes functioned as a headquarters where he brainstormed with others involved in the leadership of the movement and conducted the business of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

One of the things Nelson said he appreciated about the reverend was that money was never more important to him than the people he served. One Saturday night when Nelson was cutting his hair, King had his briefcase with him, which was filled with letters from people from all over the country. Several of the letters contained money from his supporters, donations to support his civil rights work. Some people would send him checks, but others, mainly elderly people, would send him cash. While King was sitting in his barber chair, Nelson watched as he read the letters. According to Nelson, he read each one from beginning to end, as Nelson peeked over his shoulder to see what people were writing about. “He would casually drop the money and checks down into the briefcase on the floor next to the barber chair as he read, never paying much attention to where they landed. He was more interested in what the people were saying in the letters. From my understanding, he took the time to reply to as many as he could.”

“Did King always sit in the same chair when he came to get a haircut?” I asked.

“Yes,” Nelson affirmed. “Every time he got his hair cut here, he would only sit in my chair.”

“What are some of the other memories you have of him coming here?”

“Well, there are many of them. Martin could be hilarious when he wanted to be. He had a close friend who he would meet here sometimes named Gilbert Klein, and they would always tell jokes and tease each other. I remember the time Martin told this one joke that I knew was a little out of line.”

When Gilbert Klein said to Reverend King, “Tell me a joke,” almost everybody in the barbershop turned to listen. They knew that even though the reverend was a serious guy on most days, he still had a funny side to him.

So he began telling a joke about a white man who hired this black man to chauffeur him around because both of his legs were amputated. One Sunday morning, they went to church together. The white man wanted to sit in the front of the church, so the black man pushed his wheelchair up to the front of the chapel. The black man sat outside while the service was being conducted, listening from outside, and he believed that the pastor preached a good sermon. So, when the church opened the doors for nonmembers to join, the black man walked up to the altar. The church pastor knew that he couldn’t allow the black man to join the church, because the church was all white and he didn’t want to upset any of the white members there. So, the pastor whispered in the black man’s ear, saying, “You go home and talk to Jesus and come back another time.”

A few weeks later, the black man escorted the white man back to the church service again. And again, close to the end of the church service, the pastor opened the doors of the church for nonmembers to join. The black man walked up to the altar, where the pastor was standing, and the pastor asked the black man, “What did Jesus say to you?” The black man responded, “Jesus said to tell you that you’re a no-good pastor,” and he walked out.

At eighty-four years old, Nelson still had a good sense of humor.