Читать книгу Room 207 - Kgebetli Moele - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4. Molamo

ОглавлениеMolamo

The writer, the director, the actor, the poet, the comedian, the producer, was once a tipper truck driver for a construction company. That was, as he said, a great job. Just driving up and down. He drove that ten-cubic-metre truck like Gugu coming out of that corner, whatever they call it, at Khayalami racetrack with Sarel full in his mirrors (and that’s the right way to spell Khayalami). He pushed the truck so hard that the manager didn’t know whether to let him go or keep him.

The only problem was that after he’d had his last meal of the day, after poking his pokiness, he’d start to feel uneasy and then he’d have to fight to sleep. He thought that maybe the other drivers were jealous of him and that maybe they wanted to kill him.

You know that thinking? It’s another sad black story on its own. So he went to the floor-shift people to check out what was wrong with him.

You see, we are very funny people. A black man can kill you for living your life, for trying to improve and better your life, and still come to your funeral acting very hurt. Believe it happens. Believe me, I know.

Once I had a dear friend. He was very intelligent, matriculated with six As, and won a scholarship. But, when he woke up a few days after the celebrations and joy, he was not the same friend. His mind just wasn’t his. His mind had deserted him. The floor-shift saw this and told me what their bones said. The prophets gave it their shot as well, and told the very same story. But they couldn’t retrieve his mind. His grandmother cried, but her grandchild’s mind was gone and, eventually, he died. Modern medicine could do nothing. Molamo consulted the floor-shift and they told him that he liked the job with his mind, but his heart didn’t want him to drive trucks up and down. So he asked them, “What work does my heart want me to do?”

But the floor-shift didn’t have an answer for that question.

“You can continue driving trucks, but that will result in something very bad happening to you,” they told him, so he came back to dream city to have it out with the city. To dream it out.

He was a man who talked and talked. If you gave him a beer he’d talk forever. He’d tell you the story about his uncle who came to the dream city back in the days and got himself a city girlfriend.

When his uncle was making love to the girlfriend she started moving and shaking. He stopped and looked at her. She stopped, and so he continued, but the girlfriend shook on. Then he stopped and said, “I’m doing. You are doing. You’re disturbing me. Stop that.”

He continued pleasuring her, but she started doing it again. Then he got angry and stopped.

“What are you doing? I’m doing here. You want to do?”

He took a Seven Star out of his pocket and showed it to her. Then he continued, promising her, “If you do that again, I’ll stab your butt.”

Molamo had so many of them, those stories, and he told them so well that even if he was retelling one of them, one that you had heard twenty times before, you’d die laughing. There was one that I used to love and I could have listened to it a thousand times over. I would always push him to tell that story.

He had relatives in the township and like all township houses there was a back room, a boys’ room. As the name suggests, it’s where the boys live and are allowed to do whatever boys do. When you visited them, these boys would tell you that, as a boy, if you wanted to stay with them in their boys’ room, you’d have to poke one of the female species within seven days. If you didn’t get lucky, you’d be back sleeping in the main house, and if you didn’t believe that you could poke a female in seven days, you might just as well start sleeping in the main house right away. That was the right of citizenship to the boys’ room.

Then, one day, one of their uncles from the rural areas visited. They didn’t know how to tell him about the boys’ room citizenship right. When they were about to sleep with heavy hearts, unable to do anything about the fact that he was going to sleep in the boys’ room without the right to be there, he says, “I hear that there is a rule here that in seven days I must have slept with a woman in here or I have to sleep in the main house, is that true?”

“Yes.”

“Then why didn’t you tell me?”

“Ah! Well, now you know.”

So on the eighth day, after supper, when the uncle was still having a late family chat, the boys disappeared with the key to the boys’ room and the spare keys disappeared as well. True to the rule he had to sleep in the main house.

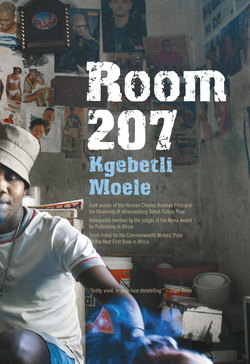

Talking about women; they gave Molamo a reason to live, or they once did. He had four children with four different mothers. The pictures that you saw on the wall of 207: they’re his mirror images. They made him so sad sometimes that he’d suddenly take them off the wall. This always happened when he was lost to the war against the Isando god’s disciples.

“I’m here living with the five of you in this one-room flat and what do I think they have eaten? What are they wearing? Do you think they are happy?”

What was I to say? He looked at me as if he expected me to come up with a comforting something, but no, I just gave him back the very same injured look that he had on. Then tears followed and I thanked myself for not having any children.

“It’s not that I don’t love my children. I love them as much as I love their mothers, but you know . . .”

He paused, looking at me, trying to fight the tears.

“You’ll never understand.”

Then, as soon as he was sober, they’d be back on the wall.

“I have them in my heart. I’m living for them and for them only.”

He was lying to himself, not me, drowning even deeper in the problems of being a grown-up.

Tebogo was his lawyer woman, the sister with the money, the car and the townhouse. One day, their little boy didn’t want to go to school – guess the boy got fed up with school for some reason. She took him to her boyfriend’s place, the one who had a fleet of cars and a degree, then she brought him to 207 to see his father, who had neither a car nor a degree.

“Do you want to stay in a rented, single room with your five friends, like your father? Don’t you want to drive very nice cars, have your very own house and enjoy your own money like Uncle Khutso?”

Note the “uncle”. Khutso was his mother’s boyfriend and a wannabe stepfather. He was trying with everything he had to get Tebogo to marry him. Molamo knew about the brother, knew that he was Tebogo’s boyfriend, or keep-company as Molamo always called him. He wasn’t threatened by him in any way.

Khutso was what the masses call the black elite. Young, black, under thirty and successful in financial terms. He had the world and all. This black elite in particular had two townhouses, a four-by-four and a couple of sports cars.

He’d pushed for four years at university without friends, without even a girlfriend. Taken refuge in books and in that way ensured his survival of UCT. He wasn’t conscious of the damage done by those lonely-wishful four years; for him everything was possible because now there was money. He didn’t have friends then, but now that he had money there were a million friends.

Khutso was expensive, a fashion parade, but all the pain and pressure that he’d felt when he was still poor was encoded somewhere in his heart. He always looked like he was trying to run away from it, looked like he was the richest man in the world.

“What is the difference between your father and Uncle Khutso?” his mother asked the other Molamo.

The other Molamo got the point and he never missed school again. The son didn’t want to be like the father.

Molamo had saved some cash while driving that heavy-duty truck and, with that money, he entered himself in that great institution of tertiary education for the second time. Paid half the tuition fees upfront. This marked the start of his personal venture in dream city.

He always called himself the “thank you-man” because that was how he paid for things.

“My ladder to the top, every step that I have passed, has a face, that I have thanked, and those faces are holding me, this ladder, together.”

You would be walking with him down Claim, going into the CBD, and he’d just stop to talk to this man or that woman from his past that he had thanked for something.

“Excuse the cliché, but no man is an island,” he would tell you afterwards. “No one is a self-made something. People can help you with a very small something, and that can help you to be a very big something. I’m still dreaming a dream because of these people and the very many things that they have done for me, and all they have had from me is a ‘thank you’. If it wasn’t for them, well, I don’t know.”

All the money he had saved dried up with the start of his second year. But he ‘thank you’ed and ‘thank you’ed until the great institution barred him from entering the examination room.

After all his hard work he became a dropout.

At the same time, Tebogo was writing her exams with a fifteen-month-old baby boy.

He’d tell you: “I packed my bags, bid farewell to this great city, but you need cash to get out of the city.”

And with that he would make me remember that first day I came to the city.

We had just passed Witbank, we were running on the N12 in an aging Japanese-made taxi. Without any music and with fifteen passengers it was tense and kind of hostile. Nobody was talking. Maybe everybody was thinking about this great city, planning how they were going to do whatever it is that they were going to do there, do it better and in a quarter of the time. I smiled. Miriam Makeba’s “Gauteng” was playing soft and sweet in my ears. Then I took a vow: When I come out of Gauteng I will be driving my own car. Well, I was still a teenager then.

Molamo was studying film and broadcasting at that great institution.

“I’m thankful that I didn’t have the money to leave then because I would have gone. But I learned to survive in this great city. I’m still here, satan. I’m the ‘thank you-man’. Let me tell you a secret: When you are with people, don’t act powerful, be humble and weak; your body language should ask for protection, and you’ll see much of the good in people,” he said, sober as a lion.

He was from a farm. He went to primary school under the care of his grandmother, which meant neglect. They had a saying on the farm: There is a crocodile in the water (meaning that you fear it, so you can’t wash). Until he went to high school there was a crocodile in the water. He went through primary school without even a toothbrush. But that was not this Molamo. These days he was a fashion parade and had to wash each and every morning, then have a late-night bath with a book in his hand. He was the most expensive of the 207s; everything that he put on was heavily priced.

With eyes that he would claim could see people’s souls and a permanent smile that made him look like he knew all things on, under and above God’s green earth, this was Molamo.