Читать книгу Room 207 - Kgebetli Moele - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1. 207

Оглавление207

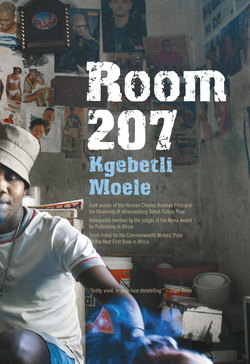

It used to be a hotel, back in the days of . . . you know, those days which the rulers of this land don’t want you to forget. Corner of Van der Merwe and Claim, there used to be a hotel. Once. Then. And now it’s a residential. I stay there in room 207. We stay there, although we don’t really say we stay there: it’s been a temporary setting, since and until . . . I can’t tell. What I do know is that we have spent eleven years not really staying there. Matome always says, “It is our locker room away from home, baba.”

This room is our safe haven during the lighted dark night of dream city.

S’busiso (we call him the Zulu-boy and, from this day on, you will call him the Zulu-boy too), Molamo, D’nice, Modishi and, like you heard, Matome ke Molobedu. For us 207 was, and is, our home.

Open the door. You are welcomed by a small passage with a white closet on your left, full of clothes and innumerable handwritten papers that are more valuable to us than our lives. Bags fill the rest of the space and on the top there is a Chinese radio, a very expensive keyboard, a trumpet, two hotplates and about a thousand condoms.

The floor is wooden, giving away the fact that this hotel was built when wood was the in-thing, fashionable. It needs help.

A door on your right leads into the bathroom.

Open the door.

The place is rotting. Some of the tiles have cracked and some have lost their grip entirely and fallen off. The cream-white paint is cracking, showing the old paint underneath and the bad paintwork done over the years. The air is humid and heavy because the small window is rarely opened and, if you do open it, you will lose your soap or maybe your toothpaste.

Before we made the rule about having the window permanently closed, toothbrushes, antiperspirants, body lotions and toothpastes vanished. Until, one day, a kilogram of washing powder vanished and Matome cried because his laundry was still dirty and no one had washed their clothes. From that day on the window was closed for good and for that reason the air is humid and heavy.

On your left is the basin, still in good condition. In front of you the toilet, missing only the toilet lid; it has never seen newspaper, and, in better times, there is always soft toilet paper – the kind the Zulu-boy prefers (that is advertised by small children on our national television). Even in the dark days, and the even darker days that may be to come, I can bet with my balls that we won’t use newspaper here, Matome will always steal – unroll the whole toilet roll from a public toilet for the comfort of our delicate butts.

Then there is the bath on your right. The ceramic coating is scratched and has, over the years, fallen victim to its own predators (whatever they are). If you had an appetite for a hot bath you’d lose it, I’m sure of that, and you’d wash in the basin instead.

Right above the back of the bath is the geyser – rusty, leaking, with exposed electric cables. Sometimes I feel sorry in advance for whoever is in the bath the day it decides it has had enough. Though, sometimes, I wish it would happen to me and then I could take the landlord to court and have the out-of-Hillbrow party that Matome says we are going to have the day we move out of Hillbrow for good.

Matome’s party doesn’t have a set date, since we all came to the dream city in different ways and, indifferently, became united. He’s always talking about it though, saying that it will be the greatest party in the history of Hillbrow.

Come in, come in.

This is the study cum dining room cum sitting room, you can sit on this single bed or that double bed, or you can just find a spot and make yourself comfortable anywhere you prefer, even on the floor. Brother, you are home.

This is our home, as you can see for yourself. This, our cum everything room, and that is our kitchen. That is the hotplate. As you can see there’s no refrigerator. That, the sink, is always like that. The dishes are washed only when we are about to have our last meal of the day, which, sometimes, is our first meal of the day but the last anyway. After that, we just put the dishes there until the next meal, then we wash and use them and put them there again, but there are no cockroaches here. Believe me, it is a miracle that we don’t have them. Go to some flats and they have forty million of them. Wage war, and sweep them away, dead, and they will be there the next day like nothing happened.

We once had a television set, it was old but it was a television. I guess it just got tired of sitting on the table and being a television, everybody looking at it when it suited them, changing the channel without its consent. One day, Modishi was having the darkest of days and hating everything with two legs and a mouth. He looked at it, maybe it asked him: “What are you looking at? I’m not on and I don’t want to be; it’s my turn to look at you guys.”

Maybe that’s what it told him because suddenly Modishi just picked it up like it was a weightless thing and threw it out of the balcony door.

The radio: Matome’s radio. These Chinese things. It no longer played compact disks and I hate when, in the morning, I’m woken up by the irritating voice of some DJ from dream city’s very own youthful radio station. I don’t hate YFM at all, but I like to wake up from my sleep very slowly. Those seconds. Those seconds in the morning when my consciousness regains itself. Those seconds when I don’t even know my other name, my hopes and dreams, while I’m thinking about my nightmares, sweet or sad, with a smile I only smile for myself – a smile I’m saving for the one that will deserve not only my love but everything that it comes with.

Anyway, it woke me, so I opened the radio up. And, since then, it’s been fighting for space with the keyboard, the hotplates and those fashionable things called condoms, which our government supplies to us, without charge, for our very own cautious pleasures.

The other citizens, those that we share this 207 haven with, the little mice, are not here now, but don’t worry too much because they will be here soon, when the time is right for them to come out. Then maybe you can have a chat with them too. Unlike the rats I kind of have a soft spot for these little mice. They don’t eat our clothes, shoes and papers. It’s like we have an agreement with them; we respect each other and each other’s property.

The only bad thing is that they scare the visiting females. They are so free that they will walk over your head, not intending to offend you in your peaceful sleep but, like you, they are chasing their own sets of dreams in dream city. They don’t eat rat poison; Ga le phirime is here but they live with it.

This, as you can see, is the wall of inspiration. To us, to me, they are not role models at all but people just like you and me, who, in their very own ways and byways, made it to the top. We put them up on the wall so that when one of us is down he can look at them, because some of them have lived through this Hillbrow, lived it to get out of it.

You know these faces, that’s Boom Shaka. If you had something cold in your hand, something cold that you were drinking when they got on stage, by the time these ladies get off-stage it will be very hot.

How?

I don’t know, but I have experienced it.

That’s the brother Herman Mashaba. Our very own self-made billionaire. He is one hell of an inspiration, if you allow me to say. Like us all here in 207, except for D’nice, he is a dropout of that great institution of education we call university. University of the North, to be precise. It is a very sad black story and we can all tell it very well.

Herman Mashaba is the green shoot that pushes itself out of the heavy ash to greater heights. Remember, that was back in the days of . . . I take off my hat, my shoes and my balls to this exceptional darkie brother of the soil. To me, he is just pure inspiration. When I’m drowning, I just take a look at this brother and he gives me a hand, pulling me out, and I know everything will be fine. Everything will be all right.

This, the second Jesus: Che.

I hate all politicians, so I hated Mandela the politician, but I loved Mandela the freedom fighter and I miss that Mandela.

Not that I miss the past.

No.

Che was a guerrilla with an AK-47 in his hands. No history needs to absolve Ernesto Guevara de la Serna. “At the risk of sounding ridiculous, let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by feelings of love.” He did say that, breathed it and died living it, and I know what you are going to say: What a waste!

Greedy.

The wall of inspiration – these brothers are there for their spiritual and soulful support only.

This is the only photo of us, which we had taken in this city at Park Station – Parkie as it is known by the masses. It was Matome’s idea as we were walking out of his office. It was taken by one of those cameramen who hang around Parkie to capture one’s first moments in this dream city.

These paintings are originals, painted by Molamo, in the rare moments when he gets a painting attack. Then he has to paint his thinking. To me they are just pictures, but every female who comes in here gets caught by this one and they end up wanting it for themselves. To me it’s just a picture of a neglected, black baby boy taking his first steps unaided, with eyes that promise the world: “I’m here.” I fail to see why the visiting females fuss about it so much.

This one has a place in this heart. This is the African warrior. The Masai warrior. Standing tall and comfortable on one leg. I guess he is looking at . . . Well, he is enjoying whatever he is looking at. It makes him comfortable and at peace. But that too is coming to its sad end, for globalisation is hungry at their door, their resistance is finally crumbling and things are finally falling apart.

Only Molamo’s Tebogo finds this one alluring, but even she doesn’t want to have it. Look carefully for it is disguised. What you are looking at is not what the painting is about. If you can look carefully in this confusion of a painting, you will see that there is a nude couple with a baby. I was not aware of this fact until Tebogo pointed it out. I wondered why she didn’t want it. She gave the reason: she wants to be part of it and she feels it rejects her every time. Then I thought, well, she is too much somehow.

These are Molamo’s stickers. This one is a quote from a great man of the soil, Ali Mazrui: “We are the people of the day before yesterday.”

And this one! I don’t think even the Almighty can put this into practice; I always fail before I even start: “You should have twenty rands that you used the day before yesterday and used yesterday, use it for today and still use it for tomorrow and all the other tomorrows.”

This is our mirror. I have seen things in this mirror; I have seen people lose themselves in front of it. I don’t know if it is because it’s a big mirror, but come here very early every morning and you’ll witness what the mirror on the wall is witness to and reflects.

This is our safe haven here in Hillbrow. I like to call Hillbrow our little mother earth in Africa because here you’ll find all races and tribes of the world. Here you’ll find Europeans and Asians that by fate have become proud South Africans, taking a long shot or maybe even a short shot at a dream or dreams of their own.

It’s dream city and here dreams die each and every second, as each and every second dreams are born. However beyond counting the dreams, they all have one thing in common: money. Respect and worship are the ultimate goals; everybody here is running away from poverty.

Poverty. I have lived too much of it. But what really is poverty? Have I really seen too much of it? Lived too much of it? Can you really measure poverty? Can you measure suffering? Can you measure joy?

I once asked a question when we were having a poverty sleep. Matome and D’nice were sharing the double bed with Modishi. I was on the sponge with Molamo and the Zulu-boy was on the single bed. As always, the room was never really dark. I can’t really remember what time it was but it was after eleven. We weren’t talking much, maybe we were saving energy or maybe we were just mad at ourselves for drinking all the money over the weekend.

The Zulu-boy was and is always the one talking, talking about that day after the out-of-Hillbrow party, when the world will be worshipping us. Talking about that day like he knew the exact date, had peeped into the future and seen it all. Now, he is just killing the time between now and then – describing in detail the convertible that Modishi will be driving up the N1, chasing the African air with Lerato on his left.

This was exactly what we needed at that moment: reassurance that our venture, this dream-venture in dream city, would pay off, eventually.

Modishi smiled privately to himself and so did I, the hunger being consumed by our joy.

Then I asked a question, “If you die of hunger while sleeping tonight and wake up in heaven, what will you say to the big Man?”

I thought they were still thinking of what they would say. But they never answered me. I tried to think of what I would say to Him. My mind got stuck with the same overwhelmed feeling that the general masses get when they meet the celebrated of His green earth.

No one said a word and we drifted off to sleep.