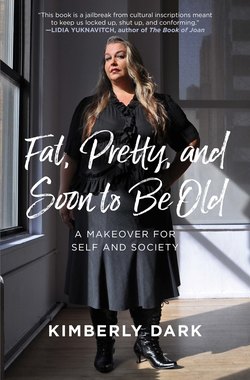

Читать книгу Fat, Pretty, and Soon to be Old - Kimberly Dark - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2. Language, Fat, and Causation

ОглавлениеThese are facts: my Body Mass Index (BMI) is over 40. This is the highest classification of the BMI, level-three obesity. Those who use this scale call me “morbidly obese.” In my culture, I am embodied as something morbid. How easy it was for language to take my life and turn it toward death and disease. And it’s not so easy to re-language myself back into full life. Let me bring this to the level of sensation. When I type or say that I am morbidly obese, something occurs in my body that was not happening just a moment before. My pulse quickens, and my head throbs. Sometimes I feel panic and want to cry. I feel like I need to take a deep breath, clear my lungs. I have been handling the themes and language of embodiment for decades, and this is still my experience with the language. It’s not like I’m dealing with a sudden diagnosis that brings a fear of the unknown. It’s not like when someone says, “You have cancer.” There is no disease in my body, no illness, yet, according to the BMI, my existence is morbid. This statement is brought to describe an everyday experience in a body that lives and acts and makes love and experiences joy. My body, that lives and acts and makes love and experiences joy, in simple, everyday ways, is labeled “morbidly obese.” I’m affected by this classification and language, and I carry the classification in the body. I feel my stress level increase just so I can tell you this—there will be effort involved in bringing this anxiety back to neutral.

There is nothing neutral about being fat in America.

It’s great that we want to talk about health, but we dwell on things that may be germane, but not causal. Let me say this another way. Numbers may be factual and still not tell the truth. We are not separate from the social sea in which we swim. Physical outcomes cannot be isolated to bodily circumstances alone. The stress of ridicule, exclusion, underemployment, diminished dating ability, and lessened respect are external forces that influence physical outcomes. Stress is culturally assigned based on appearance and especially vicious if one’s physical appearance is deemed to be one’s own fault.

I am walking up a hill a few paces behind my best friend. We are teenagers coming home late from a party. It’s ten past ten in the evening, and we are walking back to her house where I will stay the night. Our curfew is ten, and she picks up her pace to one I can’t match. This is not the first time she has done this, nor will it be the last. She often walks at a formidable speed. I am working to match her stride, but my feet hurt, and I’m tired. I wonder, as I have always wondered, if this is simply the pain I deserve for being too fat, for not exercising more. I want to keep up, and I am simultaneously angry at this desire. She should respect me and my limitations. I am sweating out this anger. Is it excess sweat because fat people sweat more? Or is it because I am unfit or because I am angry, anxious? And then, as she leaves me behind, turns the corner ahead of me for the final quarter-mile home, I am also afraid. It’s ten past ten, and it’s dark, and, before she left me behind, she said she wanted to honor her mother’s request that she be on time. And off she went, sort of trotting along the dark street. Perhaps I could keep up, but I don’t even try now. I am seething with anger at this stupidity, this humiliation, and the fear that some ill could befall me, alone, in a military-base part of town. I want to be as brave as she, but I also think she is stupid. Why would her mother prefer her arriving home alone at ten past ten rather than the pair of us arriving with apologies at ten twenty? But I am also not sure whether I deserve humiliation. I steel my demeanor and decide that I will not accept humiliation, whether or not I deserve it. In those last five minutes of the walk, I consciously slow my breathing and work on the comments that will let me save face upon entry, the comments that will reconstruct a sturdier self-image, one that is not worthy of derision, of being left behind.

When I come into the house, sweaty, seething angrily behind a cool exterior, there sits my friend, leafing through a magazine on the sofa. Her mother sits nearby. Do I imagine a look of irritation on her face for my tardiness? Does her mother think it strange that we didn’t come in together? I don’t know, and I don’t show my feelings. I hide them, as practiced, and deliver the lines I’ve constructed in the dramaturgy of social life. I take the role I’ve been handed and play it as best I can, as all young people do. I will discuss a lot of life’s joys and pains with my best friend, but not this one. She is one of the unwitting perpetrators of oppression in this regard. And I know she loves me. No, I won’t discuss this.

The experience and effect of stress on the fat body cannot be discussed independently from the stress of social interactions while fat. Down to the subtle sanctions of one’s most supportive best friends, there is stress. Does the fat person experience more discomfort during physical exertion because of the biological impact of fat on the body or because of the fear of not keeping up, being thought less than, seen poorly, fearing injury, having shoes or clothes that don’t fit well or simply can never look right. How does one weigh the fear of simply not being allowed to participate with “normal” people again? Moving easily through one’s day as a respectable social participant has everything to do with health.

And what happens when fear becomes experience again and again, when fear becomes memory? How does childhood memory embed itself in the cells of the stigmatized body? Being looked at, laughed at, sneered at, barely tolerated, not tolerated (and left behind).

According to the BMI, I am morbidly obese. This is a fact, though it is not necessarily true. The truth of how I inhabit this body is complex. It includes the duress of stigma and the joy of movement and creation. The research says that being too fat is unhealthy—“the research”— that unified thing that everyone quotes, sans specificity. Height-to-weight ratios can indeed serve as a proxy for body fat percentage—it’s not terribly reliable in describing a person’s life and health, but the process can yield data that can be factual based on specific parameters. The truth of living is complex and adaptive. I’m a storyteller in part because the truth never sits still. It dances, slumps, rolls in the dirt, and comes home after curfew. I help people understand how their particular positions and training influence what comes to be seen as truth or fiction, immutable or changeable.

Sometimes a form of hatred and scapegoating can become so imbedded in the public discourse that it becomes laudable; science seems to support it. The popularity of eugenics science comes to mind, along with the obesity epidemic as examples of how science is part of culture and vice versa. When I was a kid, I did all the same things that my slender friends did—all of them. I swam and biked and walked up hills late at night on my way home from parties. Sometimes I had a great time, though overall I resisted physical activity in the company of others. I felt fearful and pressured, and I didn’t compete well. If you would argue that because I’m fat, I did not sustain the same “health benefits” from those activities that my friends did, you must be arguing that it was because of the stress of derision or other as yet uncharted factors. There was not as much joy in my walking, my bike riding, my horseplay—this I can report. I was fearful that I would not look at home in these activities, not be welcomed, and not be entitled to live a full life in the body I have. This I can report. Stress affects my body. We are never separate from the social sea in which we swim. The social world and its science are complex and intricate. We can want many things at once, and it’s hard to tell what causes which outcomes. I turn to stories as one way to make sense of the world.

So how will I recover the emotional neutrality I lost when I used the language that associates my very being with death and disease? How do I move on comfortably? Fortunately, awareness of how language and derision affect well-being can itself be a call to healing. When we take the time to really hear what causes us pain and ill health and oppression, then it’s much easier to know that something requires redress. That’s the first step: awareness that we are living in a time of fat-hatred and that the stigmatized body requires particular care. A lot of people have stigmatized bodies—fat is just one form. People of color, disabled people, short men, very tall women, more—all bear particular social burdens and must take care. Second, I remind myself that the injury of stigma is not about me. It is separate from my body, my actions, and my life. I remember that I live in a culture that does not promote health; it promotes conformity. It’s not personal. And I have the power to promote my own health and to help others. That instantly makes me feel more alive.

The medicine for healing stress is within us. I trust that resilience and ingenuity are also embedded in the cells of the stigmatized person. Body awareness, conscious relaxation, and a will to help others are powerful health-promoters. As we come together, we can remind one another that health is also complex. We can look for and promote healing, and we can construct systems and language that promote understanding rather than just creating facts. And in doing so, we can become allies. Many who look well are not healthy. We can each bring our gifts and help each other toward greater vibrancy.

When I think back to my angry younger self trudging uphill behind my friend that night, feeling miserable and alone, I appreciate my teenage self most for this: she did not accept a simple story. Though she doubted her worth, she rewrote a narrative in which her own dignity was central. She honed her power to change perception. She learned to level her breathing, and she continued practicing joy when she could, without taking on negative labels as the truth of her identity. Her fortitude and savoir faire constructed the person I am today. During the years that I’ve been telling stories—on stage and in writing—I’ve seen audience members access their own ingenuity simply by reflecting on the examples I offer. I’ve seen others develop the ability to rewrite their own well-being, to become positive actors in their own health rather than victims of morbid narratives. The language we use to describe our bodies can illuminate pathways to good or ill health. We do well to keep looking for what serves, what heals, what connects. We do well to name those things. And to tell the truth about them in as many ways as we can find.