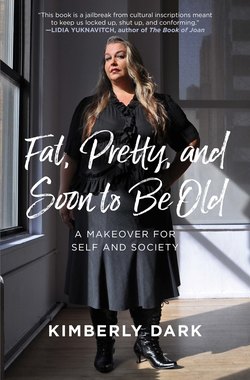

Читать книгу Fat, Pretty, and Soon to be Old - Kimberly Dark - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4. Wanted: Fat Girl

ОглавлениеMaybe I bumped her elbow. It could have been something as simple as that: the catalyst. And when she turned around to see me, her response was habitual—not calculated. She saw my face and then looked down my body and back up again with disdain, then disgust, and then she finished with a small laugh of gleeful pity. The entire assessment and pronouncement lasted a full second—not more than two.

Could I have imagined the disdain, or had there been some past interaction between us to prompt her disrespect? No, I am anonymous—and I have spent a lifetime cataloging glances such as these. I know the difference between a pullback that implies I’m taking too much space and a step-aside that extends respect for someone who needs to walk past. I’ve been thinner too, and I know that, for thin women, there are different glances (but that’s another story). Those who don’t experience them often dismiss the social sanctions that take place in mere moments. Perhaps they are imaginary, a symptom of paranoia. To those who know them, they are as real as the furniture.

To be fair, she had been drinking. It was late at night, and I was on her turf. That is, anyplace where the body is put into motion. I can sometimes get her respect in the classroom, or behind a desk, a place where my body is secondary to my mind. The hour and alcohol would make her drop the decorum she might use at, say, the post office. She would note my body shape and size, attire, and demeanor at the post office too, but the schoolgirl glee at my perceived defeat is reserved for late-night encounters, times of slight intoxication. For a place where she believes I am unarmed, unwelcome.

We had just left the dance floor, and I think I bumped her arm. We’d been out dancing, and the music was ending for the night. We were coming back to ourselves—the selves that were no longer ecstatically moving, bodies pulsing rhythm. We were coming back to the selves that have to find meaning in our own lives, make decisions about who we are, how we project ourselves onto the bright canvas of culture. The bracketed existence of dance floor anonymity was finished. And though I didn’t know the woman who gave me the look, I knew how much she needed me.

What causes one to disdain another and think it is warranted? The fact that it will be excused, or even lauded, for starters. What causes a person to dismiss the humanity of another? A need to elevate oneself in a social order where most of us help ensure that some can be disdained in order that we may flourish. And that’s why the slender girl on the dance floor needed me to be fat. While she thought she didn’t want me around, she wouldn’t have known how to live without me. And her relief that she could have been me, but wasn’t, spurred the gleeful chuckle of dismissal to her affront. I gave her life authenticity.

By the bar, late at night—this was not the time for conversation, but I caught her eye and looked for a moment with real compassion. This did not even take a second, maybe half a beat. I was so out of place in this interaction, not doing my job. And, indeed, I know how to do my job: to avert my eyes and show the shame that I feel. I felt it as a child and still do at times when someone like her catches me unaware: the shame of forgetting that I am not credible, followed by the hot rage of injustice. But not that time, and less often, the older I get. I just looked at her with compassion—so different from pity. I was not afraid that I could’ve been her. I accept that I could have been her. I might ridicule another in order to elevate myself. Of course, I could. And I knew that my ability to practice kindness toward her would help us both—and probably others whom we hadn’t even met.

I just stood and stared at her, thinking: I know how much you need me. Without me, you’d have to do something with your life in order to feel good about yourself. You couldn’t just gloat about not being me. You couldn’t use me as the ballast that keeps your head from floating away thinking of all of those on the dance floor who are prettier or thinner or shapelier than you. Without me, you’d have to make someone else your scapegoat, and it might not be so easy, if there weren’t obvious physical criteria involved. You’d have to replace me or focus on who you wanted to be within yourself—not just in comparison to others.

I wanted to ask the kind of rhetorical questions that prompt reflection in a quiet moment: What must you think of yourself to elevate the size and shape of your body—perhaps what you do to make it so—to virtue? How little must you think of yourself to look at me that way and take pleasure in it?

But she didn’t know me at all. Did my demeanor say it? Did she sense me thinking, “Maybe you didn’t know, but any fat woman you meet has character and fortitude to spare for surviving a world that uses her as you’ve just used me”? Fat people may scapegoat others to find their self-worth, surely. If she thought she was so different than me, then she didn’t know me at all.

I didn’t say any of that, but, for our similarities, I seemed to know something she didn’t. She didn’t actually need to do anything in order to be worthy of respect and positive attention in the world, and neither did I. We were already fine people, just as we were. Even as she put me down, she did not deserve my put-down. How much lower can we agree to feel? No lower. No more.

I didn’t speak at all, standing on the edge of the dance floor, late at night. But if I correctly read her painful need in her quick behavior, perhaps she read my truth in a simple stare as well. Perhaps she heard me say: “Gentle, darling. No one deserves your derision. Not even you.”