Читать книгу Sang-Thong A Dance-Drama from Thailand - King Rama II - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

When Sang Thong (The Golden Prince of the Conch Shell) is mentioned in Thailand, people respond with warmth and enthusiasm; an elderly villager will describe with relish traveling players' performances he has often seen; a taxi driver will speak of the verses he studied in the fourth grade; a young working-girl in Bangkok will describe one act she recently saw performed when she visited the place where the guardian spirit of the city resides; a professor will relate her feeling of delight as she reread Sang Thong to write notes for a student edition.

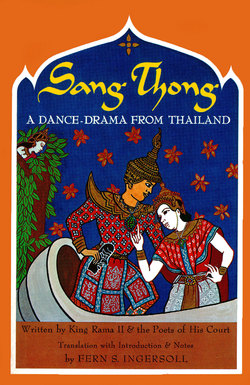

Although numerous versions of Sang Thong exist, students read and actors (to varying degrees) follow the dance-drama form written by King Rama II and the poets of his court during the first quarter of the 19th century. Yet the centuries-old plot is well known to many people in Thailand, in the villages and in the countryside, who have not read Sang Thong in this or any other version.

HISTORY: INTERACTION OF A "GREAT" AND A "LITTLE" TRADITION

The flow of ideas between a "great" tradition (perpetuated by temples and courts) and a "little" tradition (perpetuated by the common people) and back again to the "great" tradition is apparent in the history of the oral and written versions of the Sang Thong story.1 So old and widespread in Southeast Asia is this basic story, however, that it is impossible to trace its origin. From amid the currents set in motion by migrations, religious missions, and trade expeditions, and by the conquering forces that have crossed Southeast Asia for centuries, few facts can be established with certainty, though more can be reasonably surmised.

Beginnings: The Golden Shell Birth-Story

The earliest written version of the Sang Thong story in Thailand was a story called "Suvarna-Sankha-Jātak" (Golden Shell Birth-Story) in the Pannāsa Jātaka, a collection of fifty stories of the lives of the Buddha before the incarnation in which he achieved enlightenment.2 Sometime between A.D. 1400 and 1600, according to the Thai historian Prince Damrong, a Buddhist priest or group of priests in Chiang Mai (now northern Thailand) collected and wrote the stories in the Pannāsa Jātaka.3

At that time priests from Chiang Mai commonly went to study in Ceylon, where the Nipāta Jātaka, part of the Pali canon,4 was well known and highly respected. This Nipāta Jātaka, known to the English-speaking world as the Jātaka Tales, contains 547 stories in which, following upon a few words of wisdom, the Buddha explains an occurrence after his enlightenment in terms of something that happened in one of his former incarnations. The Chiang Mai priests, in an effort to strengthen the Buddhist tradition at home, seem to have translated folk tales into Pali and put them in the form of the Nipāta Jātaka.5

Although the Chiang Mai priests might have taken their material from written sources already part of the great tradition, a story of a golden prince, or a prince born hi a golden shell, does not appear in the canonical jātaka collection hi the southern Indian (Pali) tradition6 or in the two most likely collections in the northern (Sanskrit) tradition,7 Thus the story of Sang Thong may have been alive in Thailand as part of the oral tradition before it was written by the Chiang Mai priests as a story from a former life of the Buddha.

Phya Anuman Rajadhon, scholar of Thai culture and literature, feels that at least parts of the folk tale may have come from Tibet by way of the Shans, a Thai-speaking people living between the Chiang Mai and Burmese kingdoms, in what is now northeastern Burma. Dhanit Yupho, former director-general of the Thai Fine Arts Department, has written that an old Shan story (translated into English under the title "The Silver Oyster") may have contained details which contributed to the birth-story version of the Sang Thong legend.8

The possibility that the motif of a beautiful boy emerging from a conch shell came from Tibet (perhaps by way of the Shans) to Thailand seems heightened by the existence in Tibet of a cosmogonic myth including such a motif. This myth is the beginning of the genealogy of a great family of eastern Tibet, the Rlangs. Although the earliest citation we have of this genealogy is that of the fifth Dalai-Lama (A.D. 1617-82) in his Chronicle, the genealogy and the conch motif are most likely much earlier than this reference.9 The genealogy of the Rlangs begins:

From the essence of the five primordial elements a great egg came forth . . . Eighteen eggs came forth from the yolk of that great egg. The egg in the middle of the eighteen eggs, a conch egg, separated from the others. From this couch egg limbs grew, and then the five senses, all perfect, and it became a boy of such extraordinary beauty that he seemed the fulfillment of every wish.10

As early as the 8th or 9th century, Tibetan bards sang of the emergence of a hero from an egg.11

In Bengal, which has long had trade and religious connections with Tibet, Bengali women worshiping Vishnu tell a tale which is a close analogue to the first episode of Sang Thong,12 A son "of surpassing beauty" emerges from the conch shell in which he was born. His mother breaks the shell to prevent his return to it. One more folk tale, from Ceylon, mentions the birth of a prince in a chank (conch) shell.13

Combining of Motifs: Thai Creativity

Although the "child born in a conch shell" motif may thus have existed in the oral tradition of India, Ceylon, or Tibet before it was known in Thailand, the combination of this with other motifs of the episodic story may well have been a result of Thai creativity. After making a detailed study of the Thai translation of "Suvarna-Sankha-Jātaka" and comparing it with mural paintings of the Sang Thong story in a Buddhist temple in Uttaradit, a very old city between Bangkok and Chiang Mai, art historian Victor Kennedy feels that the spirit behind the combined motifs of the original Sang Thong story is the willfulness of a boy, and that Sang Thong, in a version untouched by priestly or princely interpolations, might well have begun in the Thai countryside.14

In the province of Uttaradit, where some people believe the Sang Thong story to be true, they call the ruins of a laterite enclosure the resting place of Prince Sang when disguised as a Negrito, or the polo ground where he entered the lists against Indra. Tung-yang, an old township in Uttaradit, claims to have been the city of Samon. In the province of Nakhon Sawan, close to Uttaradit Province, villagers identify a hill with the one where the ogress Phanthurat caught up with Prince Sang, The place in the stream where he magically called fishes to him is, they say, beside a rock with odd formula-like scratchings.15 People in other parts of Thailand also claim that Prince Sang's exploits occurred in or near a certain township, body of water, or promontory, though more of these claims seem to be made for the areas of Uttaradit and Nakhon Sawan than for other parts of Thailand. Thus, despite the uncertainty of scholars about the origin of the Sang Thong story, many country Thais feel the events of the tale actually happened in their own surroundings.

The Oral Tradition: "Sang Thong" and "Lakhon Nok"

During the centuries between the writing of "Suvarna-Sankha-Jātaka" and the dance-drama version of Rama II, the Sang Thong legend was a lively part of the "little" tradition of the country people. Either preserved directly from an earlier oral tradition, or translated into Thai and changed considerably from the Buddhist context of "Suvarna-Sankha-Jātaka," the Sang Thong legend was part of the type of folk drama later to be known as lakhon nok (nok: "outside") to distinguish it from drama originating in the court, known as lakhon nai (nai: "inside"). My own experience of seeing village people spontaneously begin to act out a story they are telling inclines me to think that the story may sometimes have taken dramatic form as a group of people were being amused by a storyteller.

The 17th-century account of lakhon nok quoted below (my translation) is by Simon de La Loubère, envoy of Louis XIV to the Thai king Phra Narai, who reigned at Ayutthaya A.D. 1657-88:

The presentation which is called "lacone" is a poem combining the epic and the dramatic, which goes on for three days, from eight in the morning to seven at night. These are serious stories in verse, sung by the actors who are always present [on stage] and who sing each in his turn. One of them sings the role of the story teller and the others that of the people speaking in the story; they are all men who sing and no women.16

René Nicholas, a French authority On the development of classical Siamese theater, feels that La Loubère was describing lakhon nok, because only men acted in the country and only women at court until the middle of the 19th century, when King Mongkut gave permission for women to act outside the court.17

Although the performance described by La Loubère was "serious," lakhon nok as described by later Thai and European writers was a form of drama in which actors often appealed to their audience with bawdy humor and satire. Actors sang their parts according to the general details of the story, in addition to providing humor familiar to the local audience. They sang in verses, fitting their words to dance motions which were faster and less graceful than those of court dancers.18

Court Drama: The Revival of "Sang Thong"

The Sang Thong legend moved fully into the "great" tradition again in the reign of Rama II (A.D. 1809-24), when the king and his court poets rewrote it as a dance-drama in verse form.

The final part of a written version of the Sang Thong legend had been preserved since the late 18th century, before the sack of the former capital at Ayutthaya.19 A similarity of episodes and a very few similar lines lead one to believe that this version influenced at least part of the Rama II dance-drama. The very existence of this fragment may have contributed to the desire of Rama II to recreate Sang Thong, since he probably wanted to preserve or reestablish a cultural heritage from the few remains of the Thai literary tradition.

Although there exists no dramatic version of the first act of Sang Thong other than that included with the Rama II lakhon, Prince Damrong believed that it had also been written somewhat earlier than the reign of Rama II.20 The choice of wording in Act One seems to show somewhat more concern for rhyme and less for meaning than that in the later acts. This act, upon which my close translation focuses, would, however, have had to be acceptable to the artist-king. A reconstruction of his purpose and method in composing the dance-drama is of interest, therefore, in accounting for the stylistic qualities of this first act and as an illustration of the interaction between "great" and "little" traditions.

Early in the reign of Rama II, according to Prince Damrong's history of this reign, the dancing girls in the king's court had reached a high level of performance. Thus the king must have wished to add new plays to their traditional repertoire, known collectively as lakhon nai, consisting of three plays; Ramakian, Inao, and Unrut.21 We can, of course, only suggest how Rama II and his poets may have put Sang Thong, as well as at least five other plays from the rustic lakhon nok tradition, into verses furnishing words for his chorus and rhythm for his dancers. But the early life of Rama II, as well as Prince Damrong's reconstruction of the way courtly dance-dramas were composed and tested, does explain a style in winch humorous, bawdy, "rural" sentiments came to be expressed in flowing, graceful lines.

Since the king had been brought up as a commoner in the countryside before his warrior father became king, he was quite likely acquainted with rural life as well as court life, and could still remember the ribald humor of lakhon nok as it was played for the pleasure of the people and of the spirits they wished to please. He and his poets, then, who included the famous Sunthon Phu and Rama II's eldest son, Prince Chesda, must have transformed this ribaldry into witticism acceptable to the higher classes, and then brought in the dancers to try their steps with the poetry. The poetry could then have been altered if the steps could not be fitted to it.22

Although the plot of "Suvarna-Sankha-Jātaka," the early prose story by the Chiang Mai priests, is very similar to the plot of the poetic dance-drama of Sang Thong, close comparison of the two reveals striking general differences, as well as considerable difference in details. The notion of Prince Sang as an incarnation of the Buddha, so basic to the priest's story, is not apparent in the king's version. On the other hand, the concept of kingly responsibility, which was not in the priests' version, did enter King Rama's dance-drama. The workings of karma, only implicit in the priests' story, are described and wondered about in the king's version. Animistic beliefs in spirits of trees, houses, and fields are not part of the priests' story, though they are recurrent in the king's version. The priests' story is humorless and comparatively devoid of pathos, while both these qualities are very strong in the Rama II version of the story. I am inclined to think that at least some of these differences are attributable to a "little" tradition, which, as it developed in Thailand, had been elaborating themes reflecting the feelings and everyday life of country people as they told, read aloud, or acted the story.

STYLE: PERFORMANCE OF THE DANCE-DRAMA

Staging

In Thai drama, the elements of dance, music, and narration were never separated, as they were in the West, leaving only a spoken script. For Sang Thong, this integration of dance, music, and narration has held true for both city and country productions. Thus, although the verses appearing in the translation of "The Birth of Prince Sang" are dramatic literature, they do not appear in our Western form, as a script, but rather as a combination of narration, dialogue, and directions for music. The motions of the actors in Thai lakhon have been likened to the language of the dance. These motions are frequently not those a Westerner would expect as portrayals of a given feeling, but are composed of one or a combination of several stylized motions, sometimes involving only the hands, but more likely the whole body moving rhythmically to instrumental music or to the sung narration of the story.

Through the years lakhon nok and lakhon nai have borrowed each other's technical features to some extent. In both the recent National Theater production and a demonstration by an old country-woman of the way she danced the part of Prince Sang thirty years ago, the motions were meaningfully graceful. (Since the late 19th century, when Rama IV lifted the ban on women appearing in lakhon outside the court, a woman has frequently played the role of Prince Sang, for traditionally a Thai hero has been a graceful figure.) However, in both city and country the actions of the comic characters have always been quick and unrestrained.

For National Theater productions, dancers must learn the centuries-old movements expressive of feelings; however, if a dancer is particularly admired, the slight variations with which he interprets a part may be passed on to later dancers of the role. Before the days of the National Theater, when Thailand was still an absolute monarchy, a Negrito called Kenang was featured in Sang Thong when the play was presented for the court of King Chulalongkorn (Rama V). The king had taken the Negrito into his household as an orphan child some years before. Kenang created something of a sensation in the role by playing the part without the usual mask for the acts in which Prince Sang wears the disguise of a Negrito.23

The extent to which the text was narrated by a person offstage or was sung by the players themselves seems to have varied in different places and at different times. La Loubère's account of lakhon nok at the end of the 17th century includes both a narrator and singers of parts. The style of the Rama II version indicates that, as this version was originally written, a narrator sang much of the story while dancers "spoke the language of the dance," with some ad-libbing between verses. Each verse, as indicated in the translation of Act One, usually focuses 011 one figure. Country people tell me that the last time Sang Thong was given in their village, each dancer sang his own part, describing both the situation and his feelings as he danced.

In the 1968 National Theater production of two of the later acts of Sang Thong, the main narration was sung in long verses, by a single voice alternating with a chorus line by line. In short verses there was only the single voice. The narrators sat with the percussion orchestra, just offstage. With them sat a man specially skilled in reading the lines quickly, so that the narrators could hear and repeat them. Unlike the Western prompter, the khon bawk hot was constantly active. The narrators, however, did not simply repeat what he said, but put the words to an elaborated melody and rhythm which would in turn fit with the dance. The dancers spoke their own words. (These are indicated by quotation marks in the translation of Act One, which follows.)

As Dhanit Yupho has observed, the chorus developed in connection with costuming. Thai court dancers for centuries used elaborate costumes with many traditional pieces. These costumes were so intricate that special people were needed to dress the dancers, who were, then as now, sewn into their costumes. After the costumers had performed their duties there was nothing for them to do, so they were utilized as a chorus to alternate in the narration with the primary singer. When he became director-general of the Fine Arts Department twenty years ago, Dhanit Yupho urged dancers to help dress each other as an economy measure. The tradition of the chorus, however, remained.24

As the translation of "The Birth of Prince Sang" indicates, specialized music is played between many of the verses by an ensemble consisting, in its simplest form, of a xylophone-like instrument with wooden strips, two types of drums, a reed pipe, and a small pair of cymbals. Occasionally a melody is played on one or more string instruments. This music, each rhythm of which is significantly familiar to a Thai audience, can indicate changes of scene, making scenery unnecessary. Narration and music suffice to indicate changes of time and place to the audience.

According to the emotion to be expressed, a single instrument performs, or several are played in unison. There is thus specialized music to follow the actions of a person of high status, to indicate that people of low status are leaving the scene, to express sadness, to indicate an important happening (often one which involves magic), to follow a person of high rank in the city or country, or to express the soft, sweet feelings of a love scene. Occasionally the music may accompany the speaking player, as in a love scene, but more frequently it is interspersed between verses.

Reading

Some time ago I came across a young Thai woman reading Sang Thong in a lovely singing voice. No one else was in the room. Her reading was in the thamnawng style, which children learn early in their school years as they begin to study poetry, giving distinctive rhythm and melody to different types of Thai poetry. Shyly the young Thai woman, who had been brought up in the countryside, ventured that she had been considered a good reader when she was a child. Having spent many hours watching lakhon, she had acquired its thamnawng style.

Rama II and his poets wrote Sang Thong to be sung aloud. They used a form called klon bot lakhon, in which the syllables in a line vary between six and nine. In recent years, klon bot lakhon, like other forms of poetry, has been written in two double columns. Thus what Westerners would consider a "line" begins in the left column; the next line begins on the same level in the right column. The klon hot lakhon form uses rhymes, sometimes occurring between ends of lines, but more frequently between the end of a line in one column and the middle of a line in the other column.

Alliteration and assonance, valued in Thai daily speech, are used often in klon hot lakhon, as in other forms of poetry in Thailand.

THE LIVING TRADITION IN THAILAND

Although "The Birth of Prince Sang," the first act of The Golden Prince of the Conch Shell, is no longer presented on stages in Thailand, other episodes of Sang Thong are currently produced at the National Theater, satirized by university students, and played zestfully-following the story, if not the text—at the shrine of Bangkok's guardian spirit and at town temple-fairs. All nine episodes have recently been published as a "cremation volume" honoring a respected official. City and village children become acquainted with the first act early in their schooling and with other acts in later years, as they continue their studies.

The National Theater

Sang Thong as part of the "great" tradition might have been lost when the end of the absolute monarchy in Thailand (1932) made extensive royal patronage of dancers and musicians no longer possible. However, with slow, painful efforts the National Theater was formed. So popular has Sang Thong been that in 1954 a version combining two episodes, "The Marriage of the King's Daughters" (Acts Five and Six) and "Hunting and Fishing" (Act Seven), ran through 127 performances. In 1960 one of the later acts of Sang Thong, "The Polo Match," was given. All of these productions used very elaborate scenery, unlike the lakhon nok staging by the country folk or by the court of Rama II.

Honoring the 200th anniversary (1968) of the birth of Rama II, "The Marriage of the King's Daughters" and "Hunting and Fishing" were presented in the open-air theater surrounded by the brilliantly colored roofs of the National Museum. Young and old crowded to the simple stage, children so close that they could almost touch the actors and actresses. No scenery or props were used except the traditional couch for Thai dance-drama. The narrator, chorus, actors, and actresses followed exactly the Rama II text.

University Satire

Also honoring the anniversary of Rama II, Thammasat University students presented a version of Sang Thong, "The Mother-in-Law," based on the episode in which Queen Months tries to persuade Prince Sang (disguised as a Negrito) to compete with Indra. Written by the rapier-like pen of author and journalist M. R. Kukrit Pramoj, "The Mother-in-Law" was acted with cutting satire on current figures, which M. R. Kukrit feels was part of the earliest lakhon nok style of the country people.

Shrine Offerings

Hidden behind encroaching modern buildings in the heart of Bangkok is a small shrine to its guardian spirit, the chao phaw lak mueang. Since widely known plays as well as new ones are given here continually, an episode from Sang Thong is frequently presented.

On weekends the little enclosure around the pole representing the spirit is so crowded that one can hardly move toward the tables covered with eggs, meat, steamed rice cakes, and other foods, or toward the stage where gaily dressed men and women dance, sing, and speak in the likay style. Performers of likay, a popular dramatic form developed in the 20th century, use some of the lakhon dance motions, but less artfully than do performers of lakhon nok or lakhon nai. Originally likay performers were often taught by court dancers, but this is no longer true. The likay style is freer than that of either lakhon nok or lakhon nai, and permits more ad-libbing; there is more speaking and less singing, fewer musical instruments are used (the musicians are limited to percussion instruments only), and certain sounds and intonations distinguish likay diction. Since common people find likay great fun, they feel it is an appropriate style in which to play an episode of the Sang Thong story for the spirit they wish to please.

According to the classical dancer Malulee Pinsuvana, a poor woman with some dramatic skill might go to a person who wants to repay the spirit for his good fortune. When she asks if she can play some part in return for a small amount of money, he may ask if she can play one of the characters in the story of Sang Thong, Invariably the answer will be, "I can." The date will be set; with little practice of dance steps or lines, she will play, not according to any text but from memory of the story, using some of the lines she may have heard from the Rama II version.

Although educated Thais say there is no art in likay at the shrine, their children, as well as those of common people, can be overheard urging their nurses or their parents to let them stay to the end of a performance. And so the story, though it may be presented gracelessly, becomes part of the children's lives.

Rural Performances

Ten or twenty years ago the playing of Sang Thong by a group of traveling performers, in either lakhon nok or likay style, was a common occurrence in towns and rice villages. Now it seems to be far rarer. But performances much like those at the shrine of the guardian spirit in Bangkok are still given at temple fairs in Nakhon Pathom, a provincial town.

Villagers in Sagatiam, west of Bangkok, tell of performances of Sang Thong given until about ten years ago. The head-teacher of the school taught village people the parts, and they performed in the surrounding area for various festivals or for people wishing to make repayment to the spirits for some good fortune. It is difficult to ascertain the extent to which such players followed a text or merely followed the general lines of the story, making up their words and inventing their dance movements as they went along. Today, the eyes of old and middle-aged villagers glisten as they talk of performances of Sang Thong. Mrs. Bunsong Jai-ngam, for example, daughter of a woman who often acted with the head-teacher's group, had been talking to us of past performances as she squatted on the floor washing dishes. Suddenly she put down her dishcloth, stood up, and began to dance. The words she sang, as she recalled the old performance, were exactly those of Rama II's version. The part she spontaneously danced and sang was from Act Two, in which the little Prince Sang, eager to sec the toy promised by a soldier sent to kill him, stretches out his hand and is caught. Since other village people have spontaneously related poignant portions of the drama, I am inclined to think that these especially were carried, word for word, from the "great" tradition of the courtly version to the "little" tradition of country people.

Memorial Volumes

At the cremation ceremony of a respected Thai, the family presents guests with a volume, sometimes having special meaning to the deceased or one of his relatives, sometimes chosen by the National Library as having general worth. In 1961 a special printing of the Rama II version of Sang Thong was done for the cremation of Police Lieutenant-Colonel Kowit Praphrupan. In answer to my letter asking why Sang Thong had been chosen, his older brother responded, with elegant simplicity, "It is a treasure of the Thai people."

School Programs

A piece of literature, particularly a long one, is seldom taught all at one time in Thai schools. Instead, an episode appropriate to the students' understanding is given them to read. Although many Thai students go far enough to study "The Choice of Husbands," "The Winning of Rochana," and "Hunting and Fishing," which are considered finer Thai poetry, fourth-graders already know the play from their study of "The Birth of Prince Sang."

Jaroen Jai-ngam, a Thai village teacher, explains that when "The Birth of Prince Sang" was taught twenty years ago, the only purpose was memorization of portions of the text by the school children. Today, the teacher reads the poetry to the children in the thamnawng style, which is quite different from the way "Western poetry is read. The students repeat after him, to get a feeling for the sounds. The teacher then tells the story, explaining names and trying to interest his students in the characters. (Mr. Jaroen confides that he himself likes Sang Thong better than the greater classic Ramakian, because the characters in Sang Thong seem to have more human feelings.) The children read the first part of "The Birth of Prince Sang," which has been put into simple prose. Then they read the few verses of poetry which tell of the son's feeling that it is his responsibility to help his mother in return for her care, and the teacher tries to help them feel the importance of this parent-child relationship.

Mrs. Malulee Pinsuvana, who has danced several parts in Sang Thong in the classical theater, recalls that when she was a small child and had to choose a new notebook for school, she would repeatedly buy one that had scenes from "The Birth of Prince Sang" on the cover. It is now the favorite story of her own small sons.

SANG THONG IN OTHER SOUTHEAST ASIAN COUNTRIES

The Chiang Mai priests wrote the Pamnāsa Jātaka on palm leaves in fifty bundles, according to Prince Damrong, who also noted that copies of the Pannāsa Jātaka still existed in 20th-century Luang Prabang, Laos, and Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Quite possibly copies of the Chiang Mai palm-leaf manuscripts were sent to Laos, Cambodia, and Burma, with which Chiang Mai priests had contact.

Laos

At the present time a Pali palm-leaf manuscript of the Sang Thong story, generally similar to "Suvarna-Sankha-Jātaka," exists in a Buddhist temple, Wat Ong Tue, in Vientiane. Other such manuscripts existed in the past, according to Maha Kikeo Oudom of the Library of Fine Arts in Vientiane, but were lost during the Siamese occupation of Laos in the 19th century.

In another story which is very popular in Laos, the hero, Sin Xay, has a brother called Thao Sang who, though born in a shell, has few other similarities to the Thai Prince Sang. As in the Thai version of the Sang Thong story, the queen, mother of Sin Xay and Thao Sang, is sent weeping from the kingdom because of the unnatural birth.

In northeastern Thailand, which has alternately been Laotian and Thai territory, stories about both Sin Xay and Sang Thong have been popular through the years. Between the time of a death and a cremation, when friends of the deceased stay to keep the family company, a villager will often read one of the stories from a palm-leaf manuscript. Professor Visudh Busyakul is presently translating one of these manuscripts, written in old Laotian script, in which the Sang Thong story is quite different in detail from either the "Suvarna-Sankha-Jātaka" or the Rama II Sang Thong. In this Laotian version the king and queen are even pleased with the birth of a son in a shell!

Cambodia

A Cambodian classical dance-drama known as Preas Sang follows the episodes of the Thai version from the point where Rochana chooses Prince Sang, disguised as an ugly Negrito, as her husband, to the point where the king of Samon honors his formerly despised son-in-law after the latter has engaged in combat with Indra.25

This Cambodian version does not, however, contain the birth of Prince Sang, the treachery of his father's jealous minor wife, the prince's descent to the world of the serpents, his nurture by the ogress Phanthurat, or King Yosawimon's search for his son. Thus the Preas Sang episodes performed in Cambodia are the same ones from Sang Thong currently performed by the National Theater of Thailand. In both countries other acts present in the Rama II version of Sang Thong are omitted in current performances. Possibly this similarity of staged episodes results from the influence of Thai dancers who went to Cambodia in the 18th and 19th centuries and revived the art of Cambodian classical dancing. This art had died in Cambodia when the Thais defeated Angkor (1431) and brought the Cambodian palace dancers to the Thai capital. James Brandon writes that "the Royal Cambodian Ballet of today is actually a reimportation of ancient Khmer dance, as modified by some twenty generations of Thai court artists."26 Since Rama II's version had been written by the 19th century, and since certain acts may have been performed more often than others, it is conceivable that those acts preferred in Thailand were taken to Cambodia by Thai dancers.

Burma

In Burma there seems to be little, if any, acquaintance with the Sang Thong story today. Thai scholars believe that manuscripts of the Pannāsa Jātaka sent from Chiang Mai to Burma were burned by a king who felt they were not true birth-stories.27 Although a Pali version of Pannāsa Jātaka was published 111 Rangoon in 1911, the "Suvarna-Sankha-Jātaka" was not part of it.28

Thus the presence of the Sang Thong story in some, although not all, of Southeast Asia reflects cultural differences and similarities in that area of the world.

THAI VIEWS OF LIFE IN THEIR ASIAN CONTEXT

The anthropologist Margaret Mead conceives of "cultural character" as arising out of "a circular system [in] which . . . the method of child rearing, the presence of a particular literary tradition, the nature of the domestic and public architecture, the religious beliefs, the political system, are all conditions within which a given kind of personality develops."29

Sang Thong's long period of development in Thailand, the views expressed in it, and the keen interest felt in its story by many present-day Thais place it in the literary tradition which is an integral part of the "circle" forming Thai cultural character. This drama, moreover, reflects most of the other elements mentioned by Margaret Mead in the passage quoted above.

In "The Birth of Prince Sang," as well as in later episodes of Sang Thong, views are expressed concerning the responsibility of kingship and the respect due to it, the mutually helpful relationship that should exist between a parent and child, the effects of deeds of one's past life upon one's present life, the pragmatic and manipulative use of both natural and supernatural means to achieve desired results, and the importance of status relationships. Most of these values and views of the world are expressed in some detail, as are the depictions of the particular reciprocal relationship the king has with the queen and both have with their people, the particular kinds of spirits that are thought to exist, and the ways a person tries to influence the workings of karma.

Few, if any, of the traditional views of life found in Sang Thong are distinctively Thai in the sense that individual elements cannot be found elsewhere in the world, particularly in Asia; but in their totality they form a distinctively Thai configuration. As the notes to Acts One through Nine will point out, the themes in Sang Thong, as portrayed through the dramatic events and in the attitudes of its human and mythological characters, reveal a common Hindu-Buddhist-Brahman cultural and literary heritage as well as a peculiarly Thai development in which foreign features were adapted and assimilated according to Thai values and understandings. Furthermore, Thais of diverse ranks adapted such foreign features to their own ways of life. Sang Thong in its present literary form, and as translated and summarized in this volume, comes from two divergent streams: the long process of oral transmission existing mainly among the folk, and the more sophisticated written tradition perpetuated by temple scribes and court poets. These streams inevitably continue to diverge in present-day Thailand, and both traditions carry indelible traces of Rama II's ingenious 19th-century fusion of rustic and courtly drama.